A couple of months ago the Minister of Finance announced that Anna Breman had been appointed as the next Governor of the Reserve Bank. Breman takes office on 1 December, conveniently (and sensibly) just after next week’s final Monetary Policy Statement for the year. Given the very long summer holiday the MPC gives itself, it does give her plenty of time to get her feet under the desk, get to know staff, get a bit familiar with the New Zealand data and issues before she gets to chair her first MPC and deliver the first Monetary Policy Statement on her watch. (Quite where the bank capital review is getting to isn’t clear: there was talk of publishing decisions before the end of the year, which could mean either before 1 December (in which case she has no formal say) or afterwards in which case she and rest of the Board will be making important decisions within weeks of taking up the role, in a field in which she doesn’t seem to have any particular background.)

Just a few days after the position became vacant in March I noted

Having noted that there seemed to be no ideal or compelling candidate in any of the lists of domestic names that had started to emerge, that remained pretty much my view in the abstract through the many months it took for an appointment to be made.

When Breman’s appointment was announced I was overseas on holiday. A few media outlets asked me for initial comments, including Radio New Zealand’s Morning Report who I tried to put off but eventually agreed (“live from Ravenna” – former capital of the western Roman empire – had a certain wry appeal to me). The comment I’d made to them that it was 43 years since an internal person had been appointed Governor appeared to have piqued their interest. The interview and associated report is here.

I noted that while on this occasion it was clearly necessary to go for an outsider, it was a poor reflection on the Bank, its board and senior management, over decades that it had been so long since the last internal appointment (Dick Wilks in 1982 who was then pushed into an early retirement by Muldoon), and that one dimension of successful organisations (anywhere) tended to be the development of talent and succession planning such that most (not all by any means) top appointments came from within. Among central banks, the Reserve Bank of Australia is a striking contrast. I also noted that, for example, two successive foreign appointees as Secretary to the Treasury (very unusual appointments in themselves) had not exactly proved to be stellar success stories.

There were reasons for each outside appointment as Governor – and I’m not debating the merits of any of them individually here – but the accumulated track record should be concerning. (And one of the challenges for Breman and the Bank’s board over the next few years will be building a strong second tier such that in five years time there is at least one, ideally more, credible internal candidates if Breman decided, whether for professional or family reasons, it was time to return to Europe.)

But if that backdrop is a concerning structural issue, my more immediate issue picked up the same concern I’d raised in abstract back in March: going offshore for a Governor who has no background or familiarity with New Zealand was a risky call. And if I’d contemplated a possible foreign Governor back in March I guess I’d probably have mainly thought in terms of someone from culturally and politically similar countries (Australia, Canada, UK), and Sweden is at an additional remove.

In terms of the technical side of monetary policy that isn’t an issue – Sweden has been a longstanding inflation targeter (I still have and use the nice glass plate a visiting Swedish parliamentary delegation gave me when they came to learn about the way we, who pioneered formal inflation targeting, did things decades ago) and the independent review of monetary policy done almost 25 years ago was conducted by Lars Svensson, a leading Swedish academic and later a member of Riksbank’s Executive Board (who made himself unpopular by openly expressing minority monetary policy views, which were – in my assessment – largely right). But monetary policy doesn’t operate in a vacuum – there is the context of the specific economy, of the specific political system, and of the place and record of the central bank itself. Perhaps as importantly, these days monetary policy is only one limb of what the Bank does. Much of its staff resources are now devoted to financial regulation and supervision, and that doesn’t appear to be a field in which Breman has any particular experience (for example, the Riksbank is not responsible for those functions).

So from day one it seems quite a risky appointment. I might be less worried if (a) the Reserve Bank were a high performing stable institution, b) there was a strong and respected second tier in place (who for some reason didn’t want to be Governor or who weren’t quite ready, and/or c) the appointee was a star.

As has become increasingly clear as this year has gone on, neither a) nor b) held, and (for all his faults and limitations) the departure of Christian Hawkesby only highlights how weak the top tier Breman is inheriting will be. There are two key second tier policy roles – Hawkesby’s day job (financial stability) is filled by a low profile acting person, and the macro/monetary policy side which is overseen by Karen Silk, who has such a limited background it is almost inconceivable she could have held such a role in any other modern advanced country central bank.

But nor is there any sign at all that the incoming Governor is a star. She sounds as though she probably has the temperament for the job (a person who knows her spoke quite highly of her on that score) but beyond that it isn’t clear that she is much more than a boilerplate MPC-member economist, without (it appears) that much executive management/leadership experience (let alone change management and institutional transformation). And, of course, there is no background in financial stability or regulation. She seems to have had a perfectly respectable career in the Swedish Ministry of Finance, a few years running the economics group of a Swedish bank, and then six years on the Executive Board, all against an academic background that, again while perfectly respectable, wasn’t focused on macroeconomics, financial markets, financial stability and regulation etc. She didn’t seem to have had particularly high visibility in international central banking or monetary policy circles.

One of the great things about the Riksbank is how transparent they are about monetary policy – materially more so than the Reserve Bank of New Zealand MPC, and arguably a touch beyond the optimum. Not only do Executive Board members seem to give a fair number of on-the-record speeches but all their contributions to the formal monetary policy deliberations are published verbatim. So when I got back from holiday I took some time to read pretty much all I could find from Breman. Since I didn’t previously know much more about her than her name I was genuinely curious. Some top-notch people, with distinctive perspectives, have served on the Executive Board over the years (with people brought in for full-time roles, such that it is more feasible to have mid-career people appointed than to our part-time non-executive MPC roles).

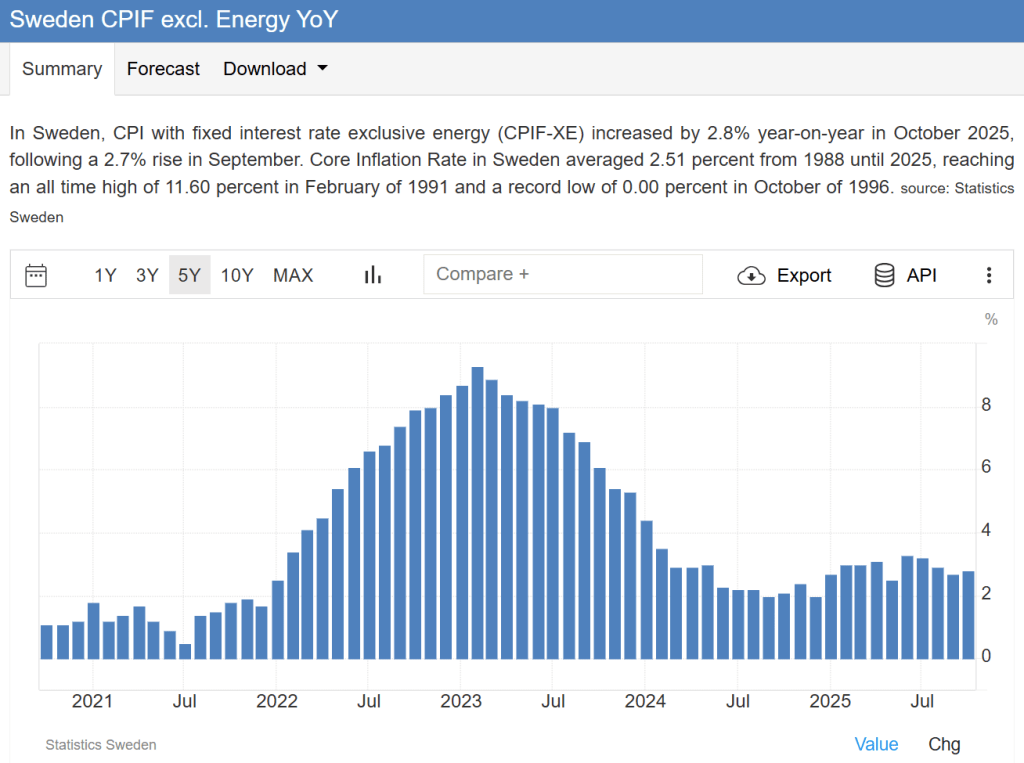

I was particularly interested in how she had contributed to monetary policy deliberations through the Covid and post-Covid inflation periods. It was a real test for central bankers, and frankly most did not show up well (which is why most – but not all – advanced economies ended up with the worst outbreak of core inflation in decades). As regular readers will know I have also long championed accountability for central bankers – real accountability with consequences, the quid pro quo for the considerable delegated power MPCs (and similar entities like the Riksbank Executive Board) wield. Other people got things wrong too, but central bankers took the job (and attendant pay and prestige) to stop outbreaks of inflation happening. If things go really badly – and they did – there should be, at very least, a strong presumption against reappointment. In fact, things went worse in Sweden than they did here – with core inflation peaking in excess of 9 per cent

And what were Breman’s contributions during this period? They were solid workman-like pieces (& her speeches were probably better than the – very few – Reserve Bank ones) but there were no interesting insights or angles, and no material (let alone votes) suggesting that her instincts or mental models were better than average – in a central bank that delivered a core inflation record worse than the average advanced country central bank. (And it doesn’t even look as though they got out the other side any better than we did – the Riksbank’s latest negative output gap estimate is very similar to the Reserve Bank’s for New Zealand.)

And so, at least on the monetary policy side, it looks like a case of a boilerplate central banker failing upwards – not at home, but promoted to the top job in an underperforming remote area of the world. Is it like being banished to the colonies in days gone by? Perhaps she’ll do just fine as MPC member and chair, but nothing in that record back home suggests we are getting, for example, a policy leader or distinctive thought leader. And is there really no price for failing so long as you are in good company?

Aside from being an outsider, it really isn’t clear what strengths she brings to the position. Perhaps under the previous government her evident enthusiasm for central banks wading into climate change issues might have been a selling point (she was last year a member of the steering committee of that central bank talk shop the Network for the Greening of the Financial System). The Riksbank apparently even puts restrictions on holding Australian state government bonds in its reserves portfolio on climate change grounds. But one had hoped that under this government they’d have been looking for a strong focus on the core statutory functions of the Bank.

One point of hope might be her expressed commitment to transparency. At the press conference she held with Nicola Willis – which featured some odd lines, including Willis claiming “we are opening a new chapter in New Zealand’s history” – there was the superficially encouraging line about how she (Breman) intended that “transparency, accountability, and clear communication will guide all the work we do”. On the monetary policy side we might look for some serious moves towards greater transparency. It isn’t her call alone, but she will over time control the appointments of the executive members of the MPC – and an earlier test will be what she does there – and it is clear that at least one non-executive member, Prasanna Gai, favours greater transparency. The Swedish experience, which she spoke positively about in a speech earlier this year, should be one of those considered seriously.

Her instincts then may be broadly sound, but a) there is no sign that she is a star, b) the culture of defensive non-transparency (transparent when it suits, obstructive when it doesn’t – I’m still engaged with the Ombudsman over charges the RB made for releasing information several years ago that should have been released – was in scope – in 2019) appears to have become quite deeply entrenched in the organisation over the last couple of decades. And much about the Reserve Bank is controlled not by the Governor but by the board – which never used to matter much but has been in the driving seat since the new legislation came into effect in 2022.

Which brings me back to the title of this post. One might have more basis for initial confidence in a little-known outsider if that person was selected/nominated and appointed by people who themselves commanded respect and had developed a track record of building (or requiring) a high-performing, lean, open, transparent, and accountable institution. But this appointment was made by Willis who had displayed spectacularly bad judgement in reappointing Neil Quigley as board chair last year, who did nothing about the board’s very bad budget calls last year (she and her officials seem not to have been aware for months), and who stood by for months while the board obstructed any clear sense of the circumstances surrounding the resignation of the previous governor. How much confidence can anyone have in a person nominated by the Quigley-led board, selected when the board was at is embattled and defensive worst, and when that board has shown no sign of having regretted anything about the way they’ve done things? The same board that really really cannot stand critical scrutiny – who instead of engaging or replying were responsible for management’s insistence to an overseas magazine that published an article critical of the Board’s record that the magazine should withdraw it and apologise for having published it. Whose acting chair – of a public agency, allegedly committed to transparency and accountability – celebrated (in writing) when the article was taken down. We are supposed to believe that these people share the incoming Governor’s stated commitments on those scores? Or to have confidence in the Minister who has sacked none of the board members, and has still not replaced Quigley as chair? They are albatrosses around Breman’s neck, no matter how good she might actually and eventually prove to be.

Way back in those RNZ remarks in September I noted “She could prove to be an excellent call. Time will tell.” We must all hope she is. The rebuilding of the Reserve Bank matters and we deserve better than we have had. Senior Reserve Bank officials have gone on record as (belatedly) recognising that confidence and trust in the Bank has taken a hit – a pretty severe one in my view. But rebuilding is going to be a tall order, the more so with such a discredited board – and would be so even for someone with excellent credentials and connections. How much more so for Breman.