Procrastinating this morning, I asked Grok to write a post in my style on yesterday’s Monetary Policy Statement. Suffice to say, I think I’ll stick to thinking and writing for myself for the time being. Among the many oddities of Grok’s product was the conviction that Adrian Orr was still Governor. Mercifully that is not so, even if – despite all the questioning yesterday – we are still no closer to getting straight answers on the explanation for the sudden, no-notice, accelerated departure of the previous Governor. Perhaps responses to OIAs will eventually help, but some basic straightforwardness from all involved – but especially Quigley and Orr himself – would seem the least that the public is owed, especially after all the damage wreaked on Orr’s watch.

Yesterday’s Monetary Policy Statement certainly made for a pleasant change of tone. Stuff’s Luke Malpass captured it nicely: “A lack of journalists being upbraided at times for not reading the materials in the hour allowed, or for asking the wrong question, was a change from previous management”. I watched about half of the Bank’s appearance at FEC this morning, and it was as if it was a whole different Bank. Not necessarily any deeper or more excellent on substance, but pleasant, respectful, engaged people accounting to Parliament, as they should. And, setting the standards low here, there wasn’t any sign of attempts to actively mislead or lie to the committee (Orr, just three months ago in only the most recent example).

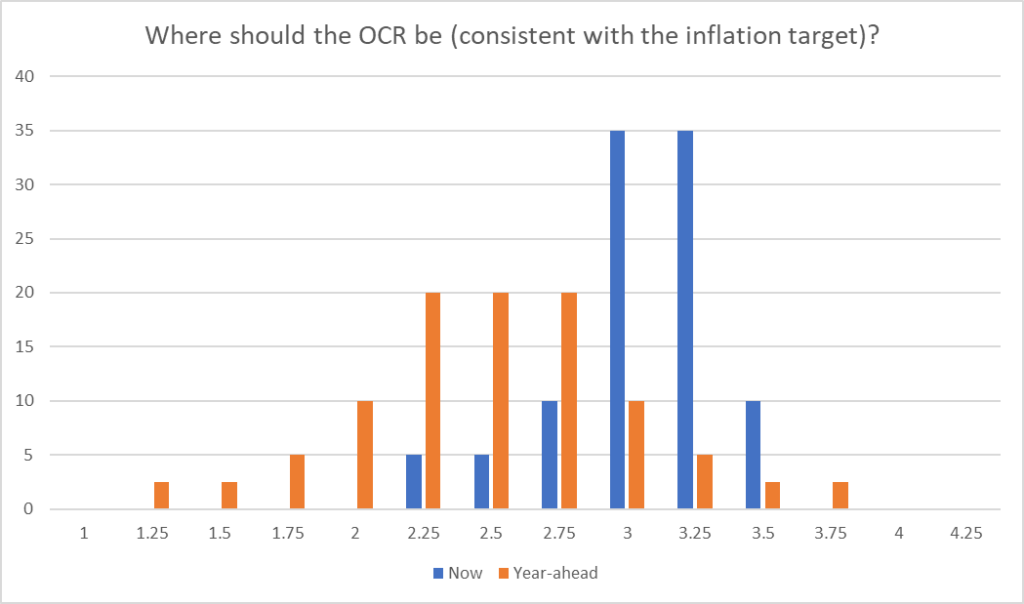

I don’t have any particular quibbles with yesterday’s OCR decision. It was probably the right thing to do with the hard information to hand, but we won’t know for quite some time whether it really was the call that was needed. The NZIER runs a Shadow Board exercise before each OCR decision where they ask various people (mostly, but not all, economists) where they think the OCR should be at this review and in 12 months time, and invites them to provide a probability distribution. I’m not part of that exercise but I put my rough distributions on Twitter earlier in the week (in truth the blue bars should probably have been distributed in a flatter distribution – we really do not know)

The Bank’s projection for the OCR troughs early next year at 2.85 per cent and, as the scenarios they present reinforce again, there is a great deal of uncertainty about just what will be required (and not just because of the Trump tariff madness and associated uncertainty).

One of the interesting aspects of yesterday was that for only the second time in the six year run of the MPC that there was a vote (5:1 for a 25 point cut rather than no change). But, of course, being the non-transparent RBNZ we do not know which member favoured no change, so cannot ask him or her to explain their position, let hold them to account or credit them when time reveals whether or not it was a good call. As it happens, despite the vote the MPC reached consensus on a forecast track for the OCR and since that track embodies a rate below 3.5 per cent as the average for the June quarter and yesterday’s was the final decision of the June quarter, I’m not sure what to make of what must really have been quite a small difference. The bigger issue remains that there is (almost always) huge uncertainty about what monetary policy will be required over the following three years (the standard RB forecast horizon) and yet never once has any MPC member dissented from the consensus track. Groupthink still appears to be very strong. And notwithstanding the Governor’s claim that there is “no bias” one way or the other for the next move or the next meeting, the track – which all the MPC agreed on – clearly implies an easing bias (even if not necessarily a large one for July rather than August).

Hawkesby, unprompted, was yesterday championing the standard approach under the agreement with the Minister which enjoins the committee to seek consensus and only vote as a last resort. He acknowledged it is now an unusual model internationally, but claims it was preferable because it means – he claims – that everyone enters the room with a completely open mind about what should be done, whereas in a voting model people tend to enter the room with a preconceived view. Perhaps it sounds good to them, but it simply doesn’t ring true (and there is no evidence their model – which, among other things, saw them lose the taxpayer $11bn – produces better results in exchange for the reduction in transparency and accountability.)

It rang about as false as yesterday’s claim from the chief economist that the uneventful (in markets) transition when Orr resigned was evidence for the desirability of the decisionmaking committee. I’m all in favour of a committee (although a better, and better designed committee) but my memory suggested (and the numbers seem to confirm) that there were also no market ructions when Don Brash resigned, in the days of the single decisionmaker model.

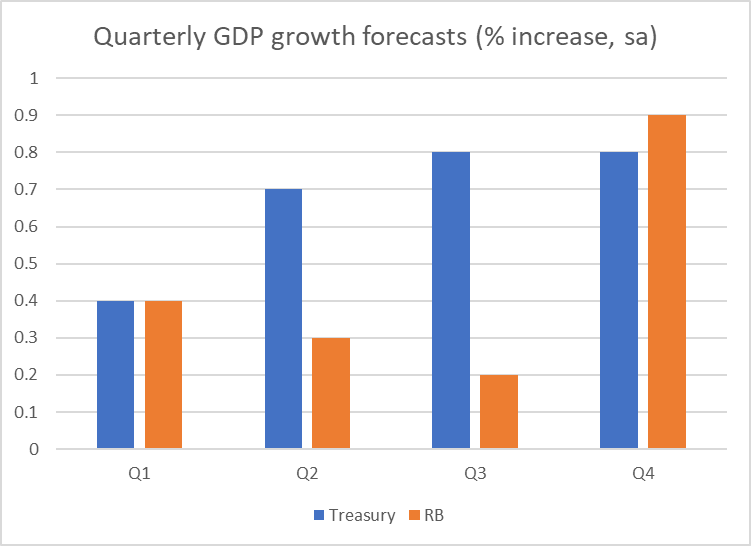

There were a few things worth noting in the numbers. First, the Reserve Bank expects much weaker GDP growth than the Treasury numbers released with the Budget last week (Treasury numbers finalised in early April)

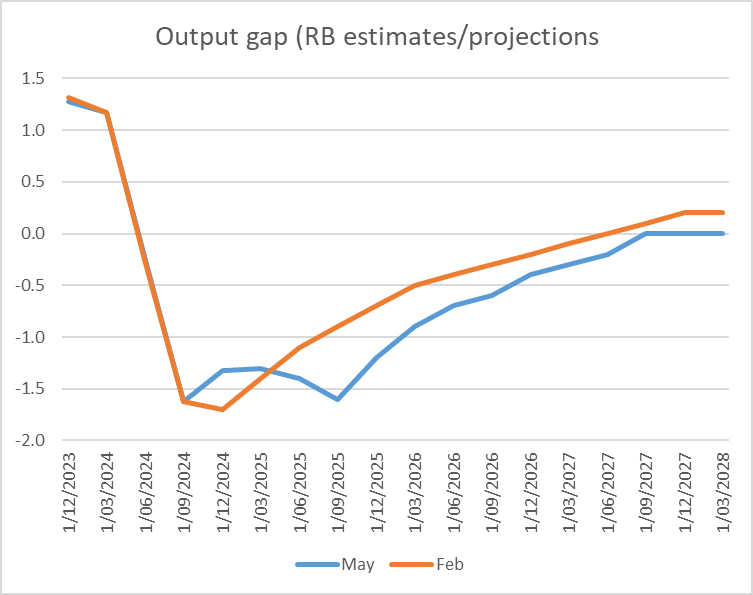

and as a result, significant excess capacity persists for materially longer than in the Bank’s February forecasts

And I’m still not sure where the rebound (above trend growth reabsorbing all the excess capacity) is really supposed to come from, on their telling, given that the OCR is still above their longer-term estimate of neutral, and never drops below it in the projection period. Reasonable people can differ on where neutral is likely to be (when the OCR was last at this level, less than three years ago, the Bank thought neutral was nearer 2%, now they estimate close to 3%), but it is the internal consistency (or lack of it) that troubles me.

I had only two more points to make, one fairly trivial, but the other not.

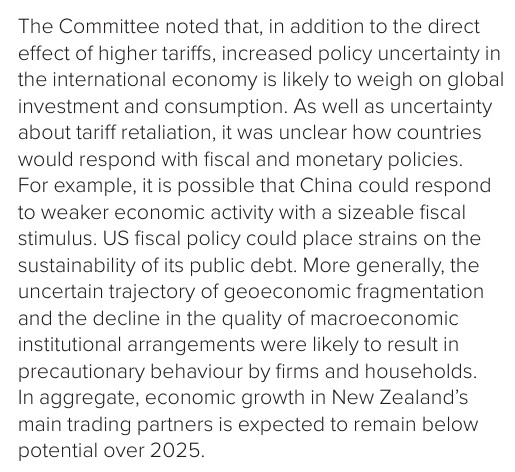

The trivial one first. In the minutes there was this paragraph about the world economy.

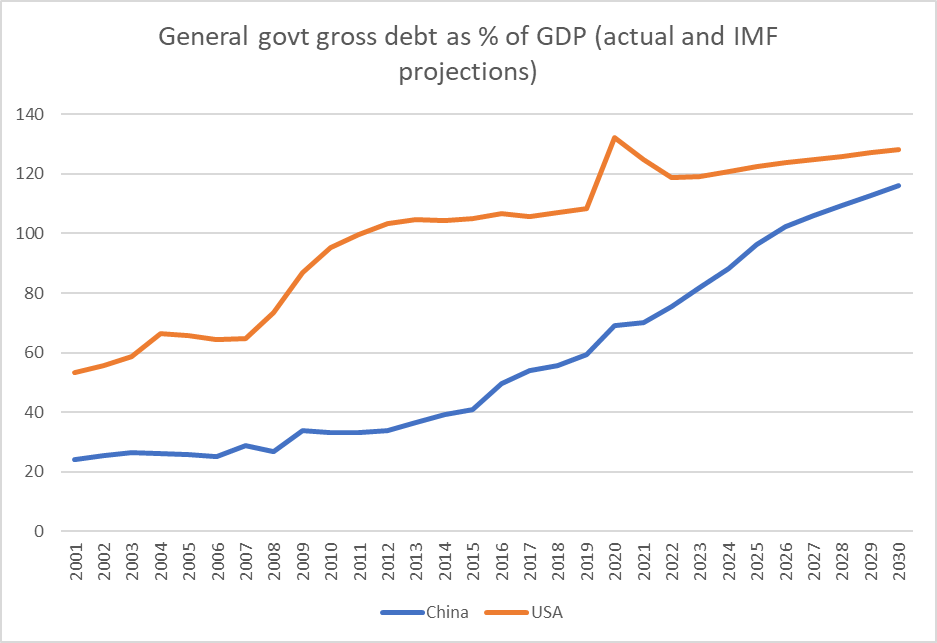

I don’t have any trouble with the (“weak world”) bottom line, but two specific comments puzzled me. The first was that difference in tone in the commentary on fiscal policy in China and the US: one might use “sizeable fiscal stimulus” (with no negative connotations) and of the other (and much more negatively) “fiscal policy could place strains on the sustainability of its public debt”. It wasn’t at all clear that the MPC realises that China’s government debt is almost as large as the US’s, and as a share of GDP has been increasing (and is expect to increase) much more rapidly than that of the US.

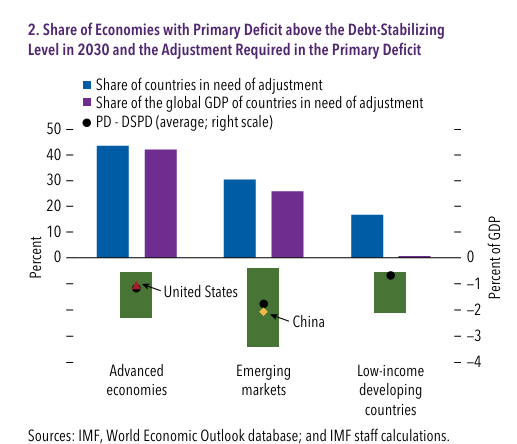

In a similar vein, this chart from the recent IMF Fiscal Monitor suggests that on IMF estimates China is already in a deeper fiscal hole, needing more fiscal adjustment (% of GDP) than the US to stabilise government debt.

Of course, the rest of the world is much more entangled with US government debt instruments than with Chinese ones, but it was a puzzling line nonetheless.

I’m also at a loss to know quite what the MPC was getting at with the line about ‘the decline in the quality of macroeconomic institutional arrangements [was] likely to result in precautionary behaviour by firms and households’. Not only is it not clear what decline they are talking about – are the Fed and the ECB not still independent, and the PBOC still far from it, and fiscal policy seems to have been on its current track for some years (in multiple countries). Is Congress bad in the US? For sure, but it has been so for a long time. I guess it might have been the relaxation of the German debt brake they had in mind, but….probably not. I was also a bit unsure how all this was supposed to play out. If, for example, there was an increased perceived risk of government debt being inflated away, wouldn’t the rational reaction be to increase purchases of goods and services on the one hand, and real assets on the other to get in before the inflation? Private indebtedness tends to rise when interest rates are modest and inflation fears are rising. In the end, who knows what they meant. Which isn’t ideal. They should tell us.

The more important issue is the Reserve Bank’s treatment of fiscal policy, where the bad old ways of Orr were again on display yesterday, in ways that really should undermine confidence in the Bank’s analytical grasp (and, frankly, its willingness to make itself unpopular by speaking truth in the face of power).

In his press conference yesterday the temporary Governor was asked about the impact of the Budget on the projections and policy decisions. He noted that they were glad to have all the information but that really it hadn’t made much difference, noting that any stimulus from the Investment Boost policy was offset by the impact of spending cuts. This is made a little more specific in the projections section of the document (a small increase in business investment, and on the other hand “on net, lower government spending reduces inflationary pressure”).

Readers with longer memories may recall that this issue first came to light a couple of years ago. Until then, for many years, the Bank had presented the impact of fiscal policy on demand primarily through the lens of the Treasury’s fiscal impulse measure, which had originally been developed for exactly that (RB) purpose. The Treasury has made some changes to that measure a few years ago which, in my view, reduce its usefulness to some extent, but certainly doesn’t eliminate it. Treasury continues to present the numbers with each Economic and Forecast Update. The basic idea is that increased taxes reduce aggregate demand and increased spending increases demand, but (for example) some spending is primarily offshore and thus doesn’t directly affect domestic demand. It is a best approximation of the overall effects on domestic demand of changes in fiscal policy. You can have a positive impulse while running a surplus (typically, if the surplus is getting smaller) or a negative one with a deficit (typically, if the deficit is getting smaller). It is straightforward standard stuff.

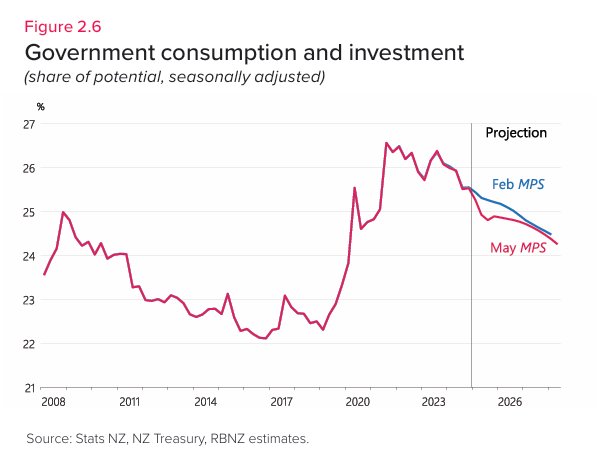

And yet two years ago the Bank simply stopped talking about this approach and replaced it with an exclusive focus on government consumption and investment spending (ie excluding all transfers – a huge component of spending – and the entire revenue side). This sort of chart has appeared ever since

and, probably not coincidentally, projections of (real) government consumption and investment have been trending downwards over that entire period. (This was the same vapourware I referred to in Monday’s fiscal post, where both Grant Robertson and Nicola Willis have repeatedly told us – and Treasury – that future spending will be cut.).

Back when this started, I OIAed the Bank for any research or analysis backing this change of approach. Had there been any of course they would already have highlighted it. There was none. But the switch had allowed the Governor to wax eloquent about how helpful fiscal policy was being, even as by standard reckonings (Treasury, IMF, anyone really) that year’s Budget had been really quite expansionary, complicating the anti-inflation drive.

The temporary Governor – who is presumed to be seeking the permanent job – seems, whether consciously or not, to be engaged in the same sort of half-baked analysis that avoids saying anything that might upset the government. Yes, on the Treasury projections government consumption and investment spending are projected to fall. But what does the Treasury fiscal impulse measure show?

At the time of the HYEFU last December, the sum of the fiscal impulses for 24/25 and 25/26 fiscal years was estimated to be -0.47 per cent of GDP (with a significant negative impulse for 25/26, thus acting as a drag on demand). By the time of last week’s Budget, not only was the impulse for 25/26 forecast to be slightly positive (this is consistent with, but not the same as, the structural deficit increasing) but the sum of the impulses for the two year was now 0.7 per cent of GDP positive. Fiscal policy, in aggregate is adding to demand (and by materially more than estimated at the last update). And the incentive effect of Investment Boost on private behaviour is on top of that.

Absent some serious supporting analysis from the Bank or its temporary Governor for its chosen approach (focus on just one bit of the fiscal accounts), it looks a lot like an institution (management and MPC) that now prefers to avoid ever suggesting that the fiscal policy effects might ever be unhelpful. After all, all else equal a positive fiscal impulse reduces the need and scope for OCR cuts – and we all know (we see their press releases) how ministers love to claim credit for OCR cuts.

If there is a better explanation, they really owe it to us. If they aren’t any longer happy with Treasury’s particular impulse estimate, they have the resources to come up with their own. But there is no decent case for simply ignoring developments in the bulk of the fiscal accounts. Wanting the quiet life simply isn’t a legitimate goal for a central banker, and if Hawkesby continues with the dodgy Orr approach – and he has been part of MPC all along – it does call into question his fitness for the permanent job. It isn’t the Reserve Bank’s job, except perhaps in extremis, to be making calls on the merits or otherwise of the fiscal choices of governments, but they are supposed to be straight with us (and, by default, with governments) on the demand and activity implications of those choices. They aren’t at present.