On two separate themes; aggregate fiscal policy, and the Investment Boost initiative.

Aggregate fiscal policy

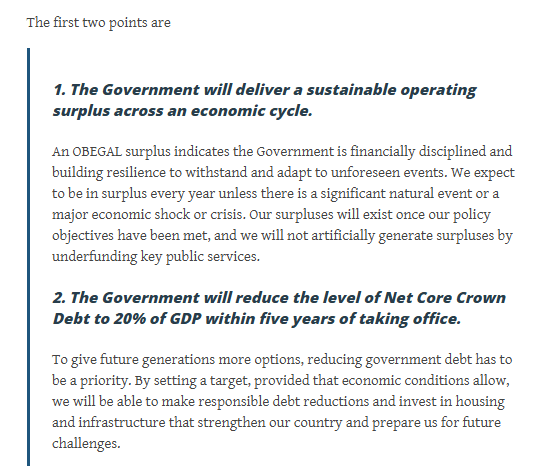

Over the weekend for some reason I was prompted to look up the Budget Responsibility Rules that Labour and the Greens committed to in early 2017 (my commentary on them here). At the time, the intention seemed to be to fix in the public mind a sense that these two parties of the left would nonetheless be responsible and prudent fiscal managers (as I recall a fair bit of the more left wing parts of the bases of the two parties lamented the agreement for giving much too much ground to what might have been thought of as orthodoxy).

And what were they promising?

The debt measure they were using at time had been 24.6 per cent of GDP in June 2016.

To which one can only say, those were the days:

- the last time there was an OBEGAL surplus was the year to June 2019, and neither government nor opposition now seem bothered by the forecast of another 3.4 per cent of GDP deficit in 25/26 (just the same as the latest estimate for 24/25). Under the current government, the preferred deficit measure has been changed, against Treasury advice, to make things seem less bad. The current government’s long-term fiscal objectives (in the Fiscal Strategy Report) still include maintaining on average “over a reasonable period of time” a zero operating deficit, but there is little practical sign it means anything to them (or that Labour now would be less bad)

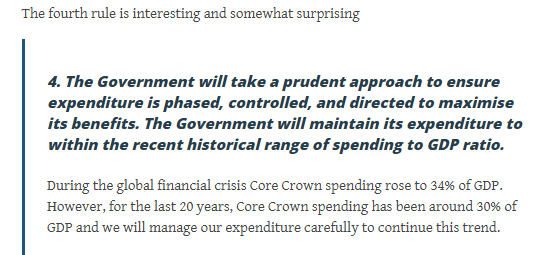

- core Crown expenses are projected to be 32.9 per cent of GDP in 25/26, up slightly from 32.7 per cent in 24/25, and down only a touch on the 33 per cent actual for 23/24. Back when Labour and the Greens made those 2017 commitments core Crown expenses were a touch under 30 per cent.

- debt measures have chopped and changed (and the current government was stuck with the additional debt their predecessors took on, although have not hesitated to take on much more since). These days, net core Crown debt is about 42 per cent of GDP. The government’s long-term fiscal goal is stated to be getting into, and keeping that measure in, a range of 20-40 per cent of GDP, but even on their rose-tinted fiscal forecasts that measure is projected to be 45.5 per cent of GDP by June 2029 (NB, that will be seven years on from the end of Covid as a big budgetary item). Meanwhile, Labour seems uncertain whether they’d attempt to even keep this debt measure below 50 per cent of GDP.

A political party today that seriously pledged to do what Labour and the Greens promised in 2017 to do (and by 2019, net core Crown debt was below 20 per cent, OBEGAL was in surplus, and core Crown expenses were below 30 per cent of GDP) would almost certainly be slammed as dangerous, extremist, unrealistic etc. So far have things fallen, under Labour and under National.

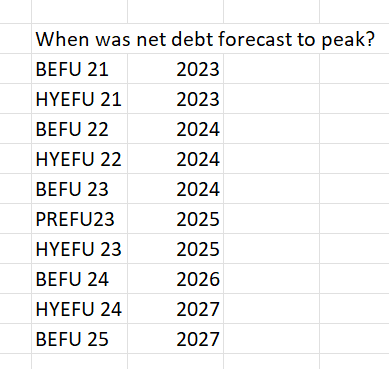

Meanwhile, too many journalists still seem to accord some degree of seriousness to fiscal projections for the end of the forecast horizon (four years out, so currently the year to June 2029). When the date for the crossover point from deficit to surplus keeps getting pushed out (and more recently, the Minister’s definition changes to make things easier), people should eventually realise that there is little or no substance to these numbers. They might be generated by The Treasury, but they aren’t some sort of best unconditional forecast, but rather the best forecast conditional on whatever successive ministers tell Treasury will be their policy for several years ahead (the end of the forecast period always, by construction) being well beyond the following election). The problem is that even if ministers honestly believe what they tell Treasury at any point in time (and probably they mostly do), it isn’t then anything more than a statement of good intention, perhaps even wishful thinking.

As an illustration of the point, consider this chart which shows projected core Crown expenses for 2025/26 as a share of GDP in successive Treasury economic and fiscal updates, going back to the end of 2021. The biggest further increases happened under Labour, but the line has continued to trend up under the current government.

Now, sure, further out the projections show core Crown expenses falling as a share of GDP, but that is sort of my point. Such projections are just vapourware. Exactly the same trend showed in the projections Treasury did under Labour (HYEFU21 to PREFU23 in this chart). It is easy, and perhaps appealing, to show such downward trends in future. It is quite another thing – politically rather than technically – to actually deliver. In both of the last two Budgets there has been plenty of hullabaloo (from politicians left and right) about expenditure cuts. But whatever the merits of those cuts, the bottom line remains that most of the proceeds have been used to increase other spending (some tax cuts last year)….and thus core Crown spending as a share of GDP is not actually falling.

Journalists, in particular (since politicians will politick), would be well-advised to ignore pretty much everything in the Treasury fiscal forecasts beyond the financial year to which the Budget actually relates (25/26 in this case), the year for which Parliament is actually being asked to make specific concrete appropriations. Most of the rest is vapourware.

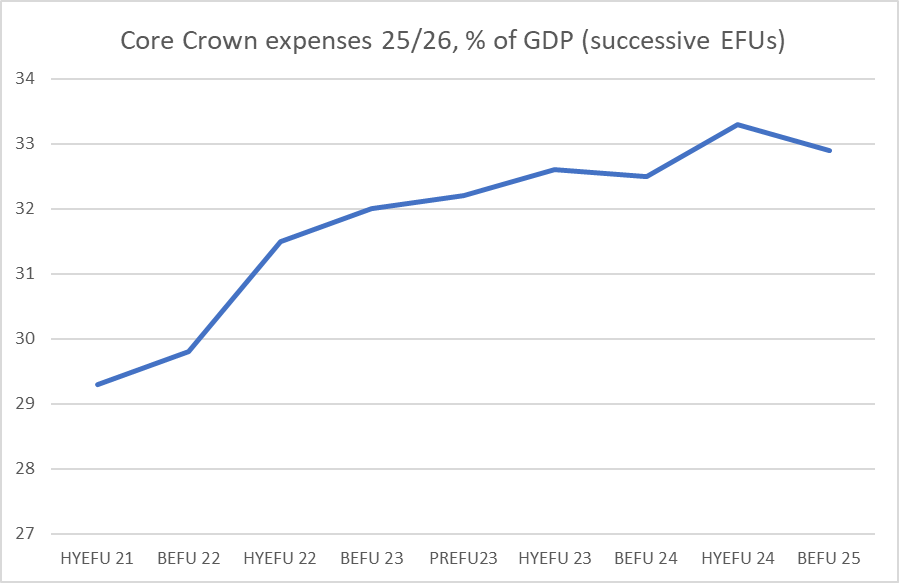

In a similar vein, here is a little table I stuck on Twitter on Saturday. The peak in net debt remains consistently two years ahead of whichever of five years’ Budgets one is looking at.

The government’s fiscal strategy seems to be not very different from that of the last couple of years of the previous government – do nothing about the long-term and in the short-term spend just as much as you possibly can without scaring the horses by blowing out the fiscal projections for net debt peaks and deficit crossovers too much in any one go.

Treasury are somewhat caught in the middle in all this. They have to forecast on the basis of fiscal policy as communicated by the Minister. That might be inescapable, but as I’ve argued previously in a PREFU context, maybe it would make sense to require Treasury to do a parallel set of forecasts showing the main fiscal variables on (a) unchanged tax rates (as at present), and b) maintaining the real per capita level of central government purchases (health, education, defence, Police etc) and the current programmes of transfers and income support. Those latter shouldn’t of course be treated as set in stone – efficiencies can be made, and different governments can have different priorities – but the expected cost if none of the expected deliverables are changed is still useful information, both for ministers (who may well already get something similar) and those seeking to hold them to account.

Investment Boost

Having been promised, by the Minister of Finance herself, “bold steps” in the Budget to address economic growth and productivity underperformance, in the end it all came down to a single measure, the so-called Investment Boost. In my quick post last Thursday I was mostly focused on the fact of the single measure and the rather underwhelming forecast change to our longer-term growth prospects (the level of GDP lifts by 1 per cent, not getting there fully for more than 20 years). [Note that this is quite similar to the then-estimated long-run effect of the 2010 tax-switch reform, which involved a switch from personal income to consumption tax and a slight increase in the corporate tax burden.] Considered against the size of gap between New Zealand average productivity and that of OECD leaders (60 per cent or more), it would represent little more than rounding error, even if the case for the new policy measure itself was strong.

I don’t envy IRD and Treasury having to come up with estimates of the economywide long-term impact of an intervention like this investment incentive. Their Regulatory Impact Statement is here, and it reports that while there have been various experiments with such policy interventions in other countries in fact there doesn’t seem to be much in the way of robust evaluations (and often these investment incentives have either been time-limited and/or applying to a materially more restricted range of assets than Investment Boost).

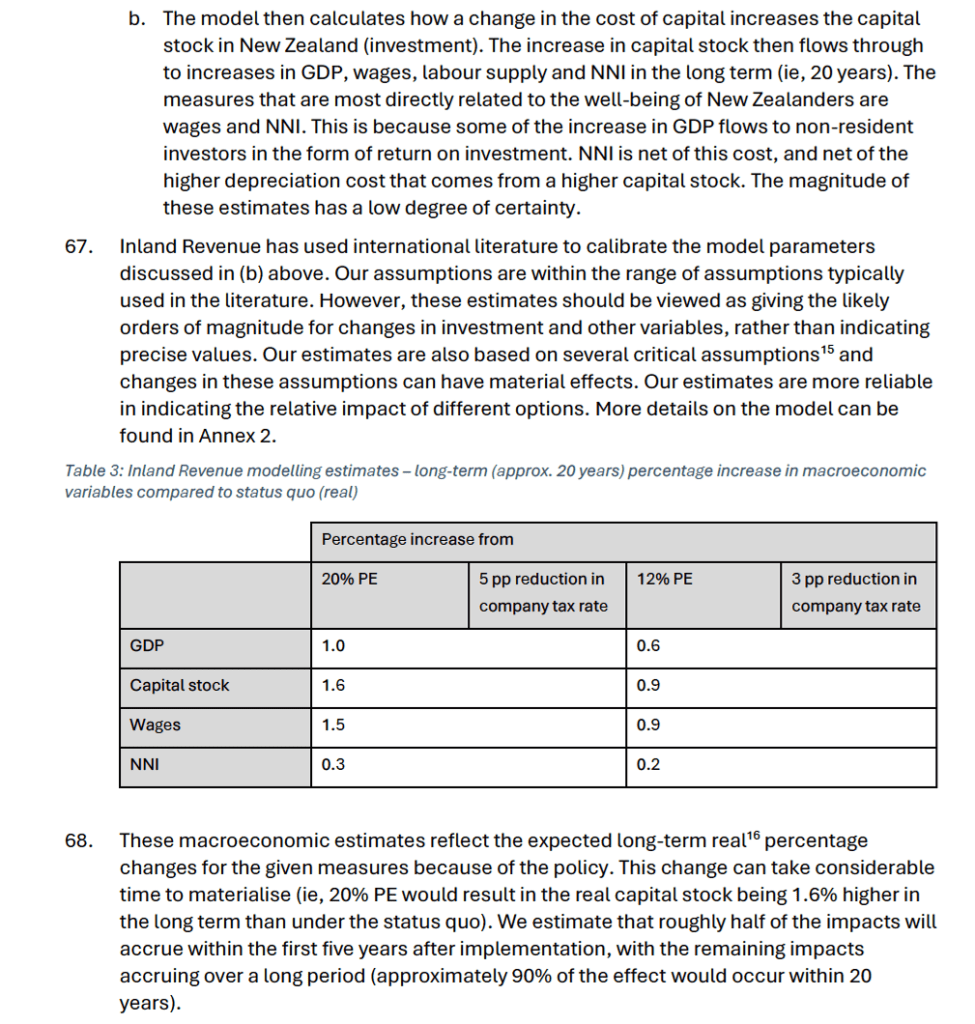

This is the bit of the RIS where they describe the economywide results

Note that in the new steady state (many years hence) GDP is 1 per cent higher than otherwise, and the capital stock is 1.6 per cent higher. Since it is stated (and both IRD and the Minister have confirmed) that the results include an increase in jobs/hours (increase in total use of labour), it is a bit difficult to see how there is likely to be any material increase in total factor productivity at all. Among the other oddities is that if total wages are rising by more than GDP, and yet the capital stock in increasing even more, the model must be generating quite a reduction in rates of return to capital. Why that is, and how plausible it is, I’ll leave to the specialists.

But perhaps more worthy of attention is that last line in the table. NNI is net national income (ie net of depreciation, and national= benefits to New Zealand residents, as distinct from “domestic” which is things generated in New Zealand, whether by New Zealand residents or foreign investors), and by far the best measure of the economic gains (or otherwise) to New Zealand. Note that NNI in New Zealand is currently about 80 per cent GDP, so – on this particular model – only 25 per cent of the lift in GDP flows through to economic benefits to New Zealand residents ((0.3/1)*0.8). Most of the GDP gains accrue to foreign investors (something IRD is certainly not hiding, but obviously wasn’t being advertised by the government). Now, to be clear, I am all in favour of facilating foreign investment, but as with almost any policy intervention the test is whether whatever benefits foreigners may pick up result in sufficient gains to New Zealanders. For interventions that cost NZ taxpayers’ lots of money (as this one does), gains to foreigners are not themselves a benefit. The question is whether they enable greater benefits for New Zealanders.

(Note that IRD makes the point that “the magnitude of these [absolute] estimates has a low degree of certainty”. But their best estimates are, presumably, what ministers had available to them.)

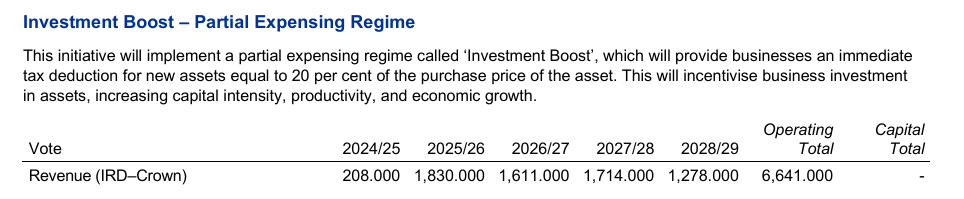

How large is the direct fiscal cost?

This is from the Summary of Initiatives document

Note that the cost in the early years is considerably higher than that by 2028/29. I presume that is reflecting the fact that for most investment the Investment Boost deduction is “just” changing the timing of the deduction (you get to write off 20 per cent of the cost in the first year, but then subsequent depreciation deductions over the remaining life of the asset are correspondingly reduced: for shorter-lived assets those reduced future deductions is significant once you are beyond the purchase year). In the RIS it is stated that that 2028/29 number is also the one they assume for the out-years (although presumably adjusting for inflation, and with a trend increase in the level of business investment – population growth etc).

And how much is $1278m per annum relative to net national income? Net national income, based on Treasury’s GDP forecasts, for 2028/29 is likely to be around $420 billion (80% of forecast GDP of $524bn), so the direct annual fiscal cost to New Zealand residents of this policy, once we get through the more expensive introductory phase, looks to be about 0.3 per cent of NNI. And that cost is being incurred every year, even though the NNI income gains don’t get up to 0.3 per cent for 20 years or more. Apply a discount rate of 8 per cent (as surely Treasury should insist on for what is a commercially-focused policy) and things could quickly look not overly attractive if a proper cost-benefit analysis had been done (it wasn’t). I guess there will be additional tax revenue on the additional GDP (tax/GDP is about 28 per cent), but again you don’t earn the tax until the real GDP benefits gradually flow through, while the fiscal cost is frontloaded. Time costs.

So perhaps the policy is net beneficial to New Zealanders (even if the scale is small). But is it an appropriate policy?

Reflecting on it further over the weekend, I’m not sure it is really either appropriate or particularly intellectually coherent. (I could add that I’m not greatly bothered by it being uncapped – so, for example, is the unemployment benefit which costs what it costs depending how many people end up unemployed, or interest deductibility etc. Government champions will no doubt add that since the point is to increase investment, if there is even more new investment than IRD/Treasury forecasts that is likely to be a good thing, not a bad thing. In some commentary I wondered if people realised that it is not a 20% grant, but rather a reduction in first year tax of 5.6 per cent of the purchase price (0.28*20).)

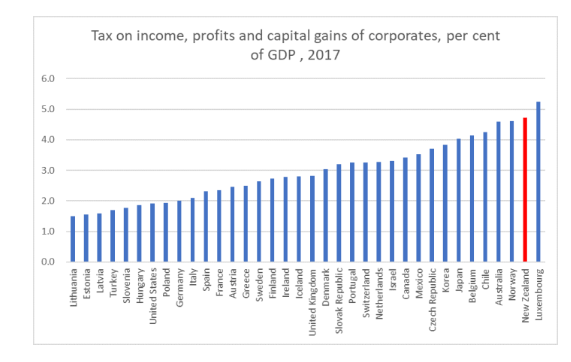

To me, there is little serious doubt that New Zealand has overtaxed business income. IRD show some of the cross-country comparisons, and they could have added this one (which is a few years old but was in the background documents for the Tax Working Group).

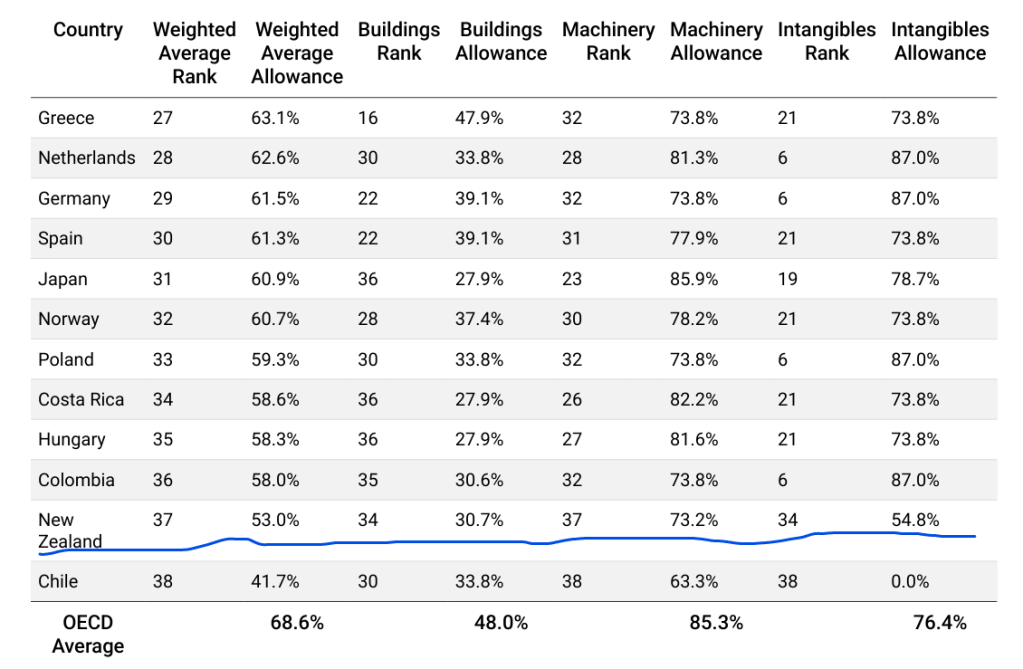

They could also have cited the Tax Foundation’s recent piece on capital cost recovery, depreciation etc. This was the bottom (worst) bit of their table for OECD countries showing the net present value of total write-offs over the life of an asset

Very few countries, for example, do as they should and inflation-adjust the value of assets to allow full real economic depreciation over the life of an asset.

But I’m still left uneasy about this particular Investment Boost initiative.

You hear a lot these days about “capital intensity” (lack thereof). For years, Treasury has talked up this rather mechanical growth accounting decomposition – business investment has been quite modest for decades, and so capital stock per worker has tended to lag – and this year ministers have taken to championing the line. And sure enough, from the RIS

There aren’t (in the views of ministers) enough capital assets, so we’ll offer an incentive (quite an expensive one) to encourage firms to have more capital assets.

The problem with this mentality – whether it is officials or ministers talking – is that it too easily fixates on symptoms rather than underlying economic causes. It never asks the question as to what is is about the New Zealand economy or its policy settings that means either New Zealand firms or foreign ones don’t seem to find that many profitable (after tax) opportunities available here (let alone look at what might be the best, or most cost-effective ways of addressing any issues thus identified.)

[Perhaps I should add here I’m old enough – as is Nicola Willis – to have been around when, a mere 15 years ago, New Zealand’s accelerated depreciation regime was scrapped – something signed off by the government (for which Willis worked at the time) and enthusiastically welcomed by Treasury (where I was working).]

Instead, there seems to have been a lurch to subsidise (one group of) inputs, even though outputs and outcomes are the things we should care about (much) more. Are more and more- highly-successful companies likely to also be engaging in more capital investment? Of course, but that is a different framing than one of “if we subsidise more capital goods will we see more highly successful companies?”

There are reasons to be ambivalent at best. For example, the goal of the policy appears to be more new investment (rather than higher GDP or NNI themselves), and thus you can get the subsidy for buying a new asset (or a used one from abroad), but not for buying an existing asset which some other might no longer need, or not be using as efficiently as your firm perhaps might. A whole new wedge is inserted, actively discouraging more efficient use of existing resources (TFP) in favour of subsidising more resources. Is that effect likely to be small enough not to worry about? Hard to tell, but (for example) very long-lived assets like factories and office buildings are caught in the net, and it is quite likely that a building won’t have the same best owner for its entire life. And what about vehicles? Some tradesman’s business fails and there is a vehicle to be sold – there is less likely to be a good recovery when a new or expanding business can get a subsidy on a new asset, but not on picking up an under-utilised existing one. And if, for small businesses in particular, there is an element of personal consumption in some business assets (be it the fancy ute or the higher-end-than-strictly-necessary laptop), lower rates of tax on business income would seem more likely to generate efficient outcomes than subsidising the purchase of capital assets. Again, perhaps small in the scheme of things, but not self-evidently an efficient approach.

Then, of course, there is the question of the intellectual coherence of the government’s approach to the taxation of business.

Last year, it was important (or so both government and Opposition believed) to remove tax depreciation from commercial buildings (otherwise the 2024 Budget numbers wouldn’t have added up), but this year new commercial buildings (including, according to the fact sheet, work already underway last Thursday) gets a 20 per cent deduction in the first year of purchase (absolutely huge upfront compared to the usual depreciation rates for buildings) – and since there is no clawback in reduced depreciation in later years, by far the biggest winners from this policy will be those adding new commercial buildings. So was tax policy last year correct – when it went one way on commercial buildings – or is correct this year, when it went quite the opposite direction? (And what was the net NNI effect of those two contradictory policy changes?)

Last year, the government also moved to reinstate interest deductibility in respect of residential rental property. The argument – which I supported totally – was that interest was and is a normal cost of doing business and as it was deductible for every other sort of company there were no good grounds for disallowing interest deductions on residential rentals. Firms need office, people need places to live, and in both cases owner-occupation will suit some but not others. So last year, residential rentals were a business like others, but this year……”residential buildings and most buildings used to provide accommodation are not eligible for Investment Boost – though there are explicit exceptions for some buildings such as hotels, hospitals, and rest homes”. Rest homes – you mean places where people live and are not owner-occupiers? I guess Rymans and the others will be happy, but where is the intellectual coherence? (And it is not as if the fact that depreciation is not allowed on residential rentals – itself a flawed policy- is a decent justification; after all, see above in respect of commercial buildings.)

Here is the main IRD/Treasury justification for excluding residential investment

As if the ultimate point was not improved household wellbeing, whether that arose via higher wages or lower real rental prices. And not a mention of last year’s policy stance, just officials and ministers again picking preferred types of capital assets.

I’m left rather ambivalent at best. There have been, and no doubt will be again (from whoever is in government) worse policies but this is simply a not very good one (despite the Minister touting apparent Treasury advice that there was something “optimal” about the 20 per cent). Had the government wanted to do something economically rational and rigorous around depreciation – see table above – it might have been better to have reinstated depreciation on buildings (residential and non) and inflation-indexed the depreciable values. But if it was coherent, it would have been a lot less catchy, since lots of machinery and software etc depreciates quickly and things like the inflation distortion matters less.

Finally, from a purely cyclical perspective, it isn’t impossible that there could be a larger short-term boost to demand and activity than implied by those long-term numbers.

Working back from the IRD cost estimate for 2025/26 ($1830m) and a company tax rate of 28 per cent suggests a base level of (covered) business investment of about $33bn. GDP is estimated at just over $450bn in 2025/26. Whatever the longer-term effects, perhaps there is reason to think the short-term lift to investment might exceed the long-term one: on the one hand, the enthusiasm effect among small businesses in particular (the policy seems to have gotten good headline reaction where it was presumably supposed to do so), and on the other, the risk/possibility that if there were to be a change of government after next year’s election this incentive could be wound back or abolished (the left would need money to fund their preferred initiatives, just as this government has – and the Greens, notably, have promised to increase company tax rates). If one were thinking of doing some capex in the next few years, the next 18 months or so might seem a particularly propitious time all else equal. A 10 per cent lift in business investment in a year would itself represent about a 0.7% lift to aggregate demand. At very least, and like all tweaky tool incentives, it will make for an interesting case study.