Former chairman of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors (and FOMC) Ben Bernanke was yesterday the first of two keynote speakers at the Reserve Bank’s conference to mark 35 years of inflation targeting, which first became a formalised thing here in New Zealand. He indicated that he’d be speaking about inflation targeting in general and then about “some lessons from the recent global inflation”. (I’ve linked to his text above, but you can also find the full session including the Q&As on the Reserve Bank’s Youtube channel).

Bernanke was the first speaker of the morning and he began his remarks, perhaps somewhat bemusedly, noting that it was “the first conference I’ve ever attended that was preceded by a concert” (half an hour or so of it apparently, including singalongs, and reportedly described by senior Reserve Bank staff as “beautiful”). That, I guess, was the Orr-led central bank to the last.

I’ve seen suggestions from a couple of people that Bernanke may have been paid some staggering amount of money to speak. He certainly still seems to command a high price on the US lecture circuit. But I’d be surprised if Bernanke cost taxpayers more than return business class airfares and associated accommodation etc. This conference was a non-commercial event inside the central banking world. And a year or two back Bernanke did a major review of forecasting for the Bank of England, and seems to have been very generous with his time and own resources. Call it a loss leader, or just something he was interested in. Either way, the British taxpayer didn’t pay much at all. [UPDATE: An OIA response from some months ago appears to confirm the fares & accommodation only basis for Bernanke.]

Unfortunately, if Bernanke didn’t cost much, he didn’t offer much beyond his name. It was a fairly short speech (7.5 pages of text), the first two-thirds of which was about inflation targeting in general. It would be really surprising if anyone at the conference either learned anything new from that section or was prompted to think differently about any aspect of monetary policy or inflation targeting. It was almost entirely descriptive, with no attempts to suggest refinements or even to knock down what he might think were dead-end suggested variants. There wasn’t even a mention – amid the observation that the Fed’s target is “well understood by financial markets, legislators, and other observers” – of the questionable experiment with “flexible average inflation targeting”.

Close readers might note that he apparently takes for granted that “clarity about the strategy – and internal debates about the strategy [emphasis added] – also helps the public understand and predict how policy is likely to change when…the world evolves in unexpected ways”. If anyone had noticed, no one questioned him about this observation, which is of course quite at odds with how the New Zealand Monetary Policy Committee has operated since its inception. There is little sign that debates even exist, let alone the nature of them.

He also noted that inflation targeting “does not prevent policy mistakes”, but then he didn’t identify any of those, whether from his own experience or from his subsequent observation as a scholar, let alone discuss the nature of mistakes, or how we learn from them or how policymakers might be held to account.

All in all, it was very much a complacent end-of-history and inside-the-club sort of treatment. I suppose everyone wants to feel good about what they do, and Bernanke is certainly an eminent person to bestow his blessing (Nobel Memorial Prize and all). But it was advertised as a research conference – something about learning, improving, evaluating etc. And there was none of that from Bernanke. Unfortunately it reminded me of his 2022 book, 21st Century Monetary Policy, which also erred sufficiently on the complacent side as to make it of little interest beyond perhaps an undergraduate (or similar) audience.

There was perhaps more interest in the final 2.5 pages devoted to the inflation of the last few years. Unfortunately his story – which, admittedly, might have warmed the heart of the Governor if he’d been there and hadn’t resigned and stormed off the day before – wasn’t very convincing either.

In fact, it was really quite astonishing that there was no analysis and almost no discussion of monetary policy at all. There was not even any mention of central bank responses during the early stages of the pandemic itself. What there was was the claim – supported by no analysis at all – that “my overall conclusion is that, in terms of actual policy choices, most central banks did about as well as they could in the post-pandemic period, given what they knew at the time”.

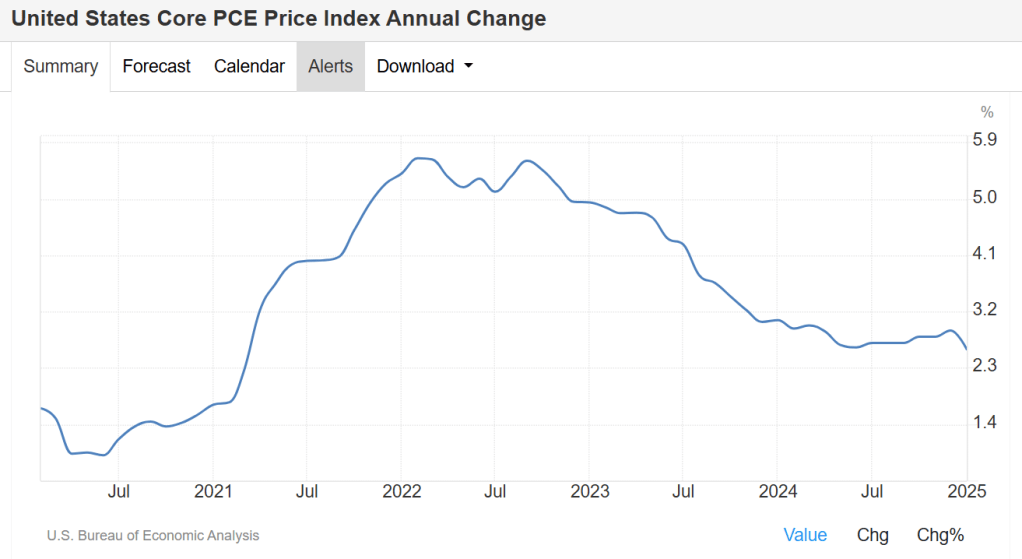

Which is pretty remarkable when you realise that, to take just the US as an example, annual core PCE inflation – core PCE is the one the Fed tends to focus on, and which removes food and energy – peaked in February 2022. The Fed’s first increase in its policy target rate came in March 2022.

Bernanke devotes considerable space to the question of whether (pandemic and post-pandemic) fiscal policy caused the outbreak of inflation. Of course it didn’t, because monetary policymakers (a) know about fiscal policy news, and b) move last. Except at the extremes of fiscal dominance – not even close to being reached in advanced economies in recent decades – fiscal policy is never the primary culprit. If it was, we wouldn’t have made central banks independent. You can have bad or good fiscal policy, necessary, wise, or otherwise, and monetary policy is supposed to counter the (core) inflation effects. And no one really doubts that monetary policy settings once the pandemic really took hold – and for a couple of years thereafter – were expansionary not contractionary.

With hindsight – and only really with hindsight – it might at least be reasonable to note that the initial monetary easing was unnecessary and inappropriate (central banks – and markets – simply didn’t understand pandemic macro well enough). And it is pretty universally acknowledged now that (almost all) central banks were slow to begin to tighten again (even Orr has reluctantly acknowledged that the RBNZ should have started sooner). But apparently that wasn’t something Bernanke wanted to touch on even in passing, perhaps taking politeness to your central banking hosts rather to an extreme.

The essence of Bernanke’s arguments is here

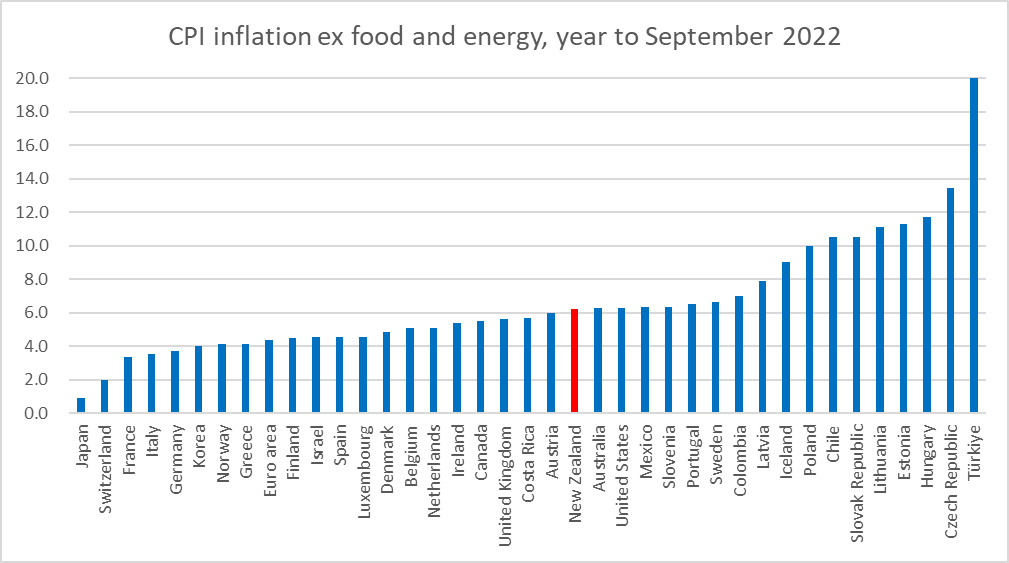

This paper got a fair amount of attention when it was published in 2023. The Reserve Bank even did a version here which, as Bernanke notes, found a larger role for demand – and thus monetary policy – factors. The paper looked at quite a range of variables, but the centrepiece was around headline CPI inflation. Headline inflation, of course, gets affected by the sorts of supply shocks to prices (energy and food) that we saw, in particular, around the time of the invasion of Ukraine. As he notes, headline inflation in Europe was particularly badly affected by the extreme gas price shock (something not affecting NZ at all, detached as we are from the global LNG market).

Central banks though (rightly) tend not to focus on headline inflation – worrying only about whether headline effects spill into inflation expectations and then into price and wage-setting behaviour over longer horizons. Now, simply excluding food and energy inflation isn’t the only sort of core measure central banks and other analysts like to look add in difficult times, but it is what we have reasonably consistent international data for.

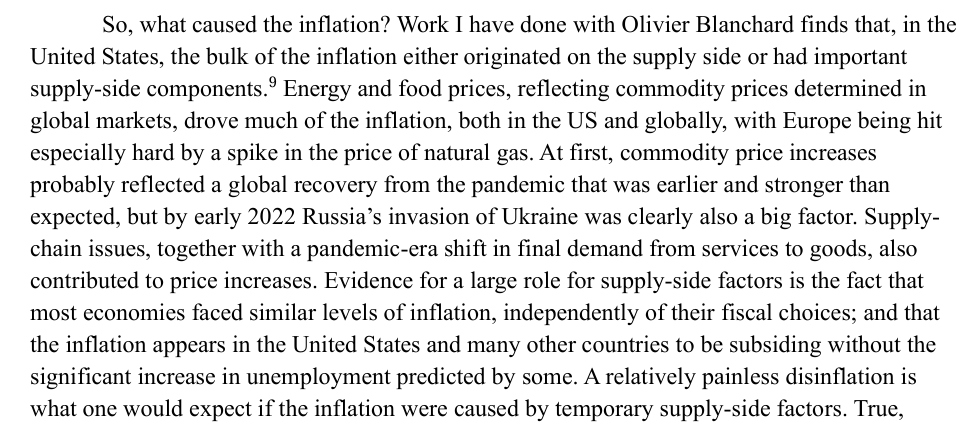

Bernanke claims as evidence for his story that “most economies faced similar levels of inflation, independently of their fiscal choices”. But even on headline inflation that isn’t really so.

which is a much greater degree of cross-country variation than we were seeing pre-Covid, even if one discounts the (geographically specific) gas price shock countries at the far right of the chart.

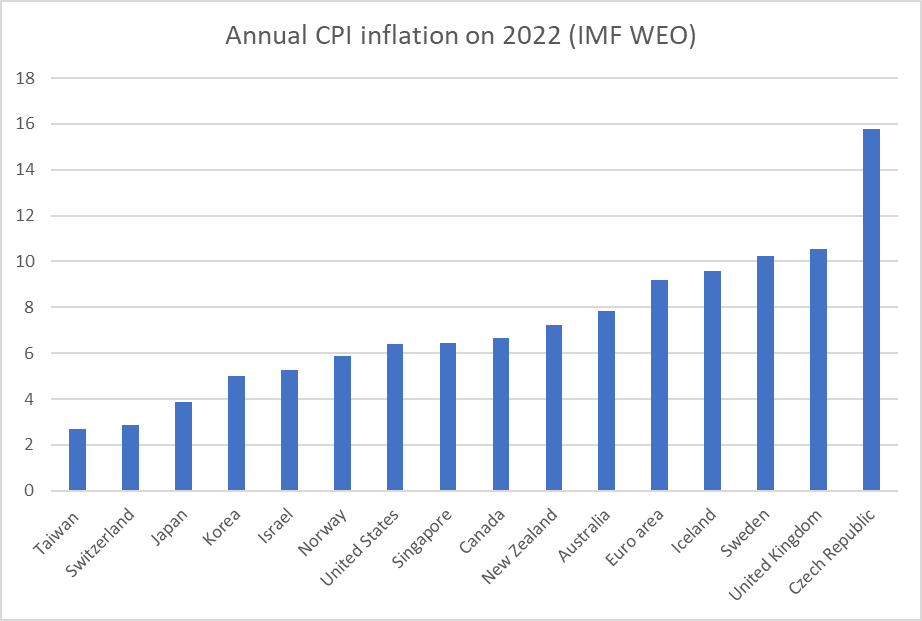

As for core CPI inflation (ex food and energy), the OECD databases have become painful to use, but I dug this chart out of an old post (ideally I’d show all the euro-area countries just as a single observation, although you can see the overall euro area number towards the left of the chart)

Quite some cross-country variation (even excluding the monetarily wayward Turkey). Is it, for example, pure coincidence that the two OECD central banks that didn’t ease monetary policy going into Covid – Japan and Switzerland – managed the lowest inflation? And to the extent that there was similarity- recall, this is in core inflation – across some countries (eg US, NZ and Australia) mightn’t it possibly reflect something about common mindsets and approaches to policy (and even, across those three countries, a fairly common pace of rebound in GDP following the initial 2020 lockdowns etc)?

And if the primary driver for (core measures) of inflation was really supply shocks (that should be largely looked through) rather than central bank choices, there must surely be at least two outstanding questions:

- Why is it that all (or certainly almost all – someone can to point me to an exception if they know of one) advanced country central banks would still today describe their monetary policy stance as being on the restrictive side of neutral? The ECB eased today, to 2.5 per cent, and repeated that interpretation of their policy rate, and it is certainly the RBA and RBNZ stance. (For the US things might be different. Policy is still described as restrictive, but while Bernanke noted that the CBO estimate of the output gap for the US in 2021 and 2022 never got very large (IMF estimates show the same thing), the most CBO recent estimates for the end of last year now point to a large and growing positive output gap.)

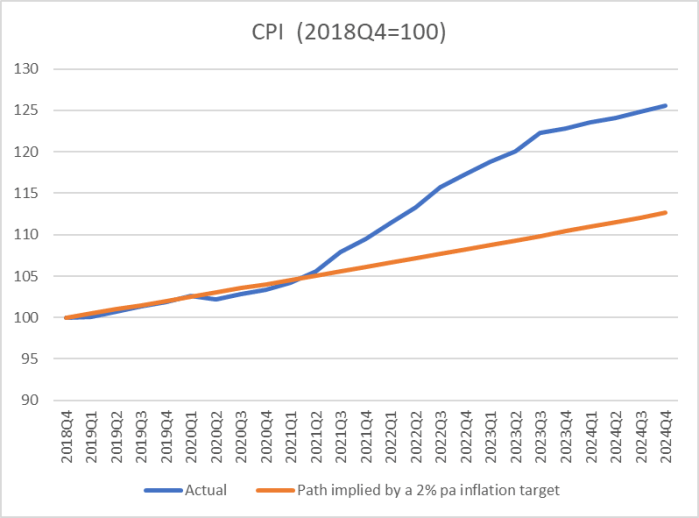

- If the story of the surge in inflation really was mostly about supply shocks why, given that those shocks have now fully reversed hasn’t the price level dropped back? Even in nominal USD terms, world oil prices are back to around where they were in 2018 and 2019, the same goes for wheat, and even European gas prices don’t seem dramatically higher in real terms than they were before the pandemic and war. In all cases, real prices have fallen a lot (shipping and componentry disruptions also largely sorted themselves out), and there simply has not been any period in which headline inflation has substantially undershot the core measures, while the price level – headline or core – remains well above the trajectory implied by central bank targets projected forward from 2019. Central banks don’t pursue price level targets, but successful flexible inflation targeting, that simply looked through the ups and downs of supply shocks to prices (when shocks fairly quickly reverse), would look a lot like medium-term price level targeting. Here is what a chart for New Zealand looks like

In broad outline, this sort of chart for many other advanced countries would look quite similar.

I don’t think anyone accuses central banks of malevolence during the last few years (Covid and inflation). No doubt they were all trying to do their best. But the evidence just isn’t there to support Bernanke’s claim that they did as well as they could have with the information they had (unless that last phrase is somehow shorthand for “on the mental models they happened to be using”, which unfortunately too often turned out to be wrong).

You can’t cover everything in a fairly short speech, but it was also worth noting that there was no mention of the (really large) losses incurred by taxpayers from the QE-type operations (bond purchases) undertaken by central banks during the Covid period, when bond yields were already at extraordinarily low levels. In his book, finished about three years ago, he affected a fairly blithe indifference, noting that any losses this time could be considered against the gains central banks had made on earlier QE. That seemed a pretty rash approach to public sector risk-taking, and would be small comfort to taxpayers in places like Australia and New Zealand where the central banks had not previously done QE. (In fairness, one can make a slightly stronger argument for the QE – beyond the immediate crisis of March 2020 – in the US, where long rates really matter, than here.)

And of course, because pretty much all the chaps (of either sex) had really done their best, there was of course nothing in Bernanke’s discussion about practical accountability. It might at least have been interesting to hear him on that in principle – what would or should it take for powerful independent decisionmakers to warrant losing their jobs? Again, the US system is different than ours (and in fact each country has different specific provisions for removal) but the price of operational autonomy was supposed to be serious accountability – something more, at least when inflation targeting was conceived and idealism was afoot, than just marking your own performance after the event, with barely a hint of contrition.

It was a shame. Surely Bernanke could have offered something deeper and more stimulating (it didn’t even stimulate searching questions from the floor). Then again, I guess Orr and his team had chosen him deliberately. And they’ll have been rather pleased with that “did as well as they could” summary assessment. Wouldn’t want any awkwardness now would we? (Other perhaps than the unplanned unexpected absence of the Governor from his own “celebration” – the word Acting Governor Hawkesby had used in introducing Bernanke.)

Doing monetary policy well in tough times isn’t easy. Glib lines about “it is only about 25bps up and down every so often” are just that – glib. Humans make mistakes, but they – and their institutions – learn when they are willing to confront and explore them.

This made me spit out my coffee – ‘China poaches US talent after being fired in Musk’s mass layoffs.’

LikeLiked by 1 person

Trump is using fiscal contraction to target inflation and reduce interest rates by smashing domestic demand in the US economy with mass layoffs – public and private sector. This is being done to mitigate the inflationary impact of the tariffs and speed up the fall of interest rates. So, it’s cohesive in that sense and not dissimilar to what Willis did last year in NZ.

However, in a globalised labour market, countries that are conducting expansionary fiscal policy with a goal of low unemployment will soak up the un-used skills and IP.

This is exactly what happens to NZ – our unemployed young, skilled and educated people leave to countries that can give them work. And this happens every time we decide as a nation that we need to have a deliberately created recession. And now the US may experience the same thing with China as China soaks up the unemployed young, skilled and educated workers from the US.

LikeLike

Trump’s policies are almost certain to be materially fiscal expansionary (for good or – in my view – mostly ill)

LikeLike

How do you mean? In terms of government spending into the economy his policies will be contractionary – surely? They want to reduce federal spending from 6% to 3% of GDP. Is that not contractionary?

Or are you referring to the amount of new bonds that will need to be issued – which is going to grow?

LikeLike

Mostly that they are looking to extend large tax cuts that were due to roll off shortly, and are only proposing to cover about half of that cost with expenditure savings. All the stuff around DOGE and USAID etc is sound and fury with not much macroeconomic content, because the dollars involved are really tiny compared to the scale of US govt tax and transfer and defence spending policies (and financing costs)

LikeLike

In NZ the fact that our unemployed can move offshore and find work relatively easily may reduce the impact or rising unemployment on wage inflation because the unemployment rate does not rise as high as it would in a closed labour market. It will be interesting to see how unemployment unfolds this year and what happens with net migration at the same time.

LikeLike

Tax revenue in the US is going to fall for two reasons – tax cuts and a contracting economy. The overall quantity of new money being put into the economy by the US government day to day is going to reduce. As a consequence, private sector credit growth (for investment and hiring) is also going to reduce – from whatever level they are at now to a lower level over time.

I.e. the US economy is becoming smaller than it was.

The size of the governments outstanding bond issuance is going to grow as you say – but may not rase the interest rates on government debt. I think the interest rate on long term US debt is actually falling because of recession concerns.

Final MMT point about the interest paid on government debt. Where does the interest payment on public debt go – it goes into the private sector – it is income and savings for the private sector – the credit side of the government debit.

LikeLike

That fall in interest rates on US government debt may be the purpose of the other Trump policies and a recession in the US will generate huge demand for US Treasuries. That demand could be used to fill the gap between spending and taxation that you are highlighting. That’s my theory and I think it’s a pretty good one!

LikeLike

Trust me Michael – there are much bigger cuts coming to the federal workforce – DOGE might be over but the mantel and modus operandi has been passed on to the heads of the federal agencies themselves. Congress has already provisionally approved $4 Trillion in tax cuts to ensure a fete accompli on spending cuts. This is going to hurt and be painful to watch over 2025. China must be sitting there, scratching their heads and thinking – “why is the US government economically attacking their own population?”

LikeLike

But if China started selling some of its vast holding of US Treasuries that would push up the interest rate. They wouldn’t do that would they?

LikeLike