That’s the title of a 2024 book by a couple of Australian academic economists, Steven Hamilton (based in US) and Richard Holden (a professor at the University of New South Wales). The subtitle of the book is “How we crushed the curve but lost the race”.

It is easy to get off on the wrong foot with at least one of the authors. Each of them has a Foreword, and Hamilton’s rubs me up the wrong way every time I come back to it (as I did just now). There are 26 “I’s” in 2.5 pages (he notes “I am the first to admit I can be prone to self-congratulation”) and then this moan

I do love Australia but boy do we love credentialism. Australia is a country where time served is taken far more seriously than the merits of an argument. Where, unless you have some postnominals, a regular column writing in a national broadsheet, or went to the right private school, the typical journalist won’t give you the time of day. The policy discussion is fundamentally undemocratic, and the country is poorer for it.

Which seemed a little odd for someone who is an assistant professor in another country and has just had a book, on policy in Australia, published by an Australian university press. In fact, I looked up Hamilton’s bio. It has 7 pages of listings under “Opinion Writing” (130 or so pieces), and the bulk of those articles/columns were published in top Australian newspapers (AFR, Australian, SMH). Not bad for a junior academic living in another country.

The title of the book is a bit of a puzzle. In places, the story is that Australia did some things exceptionally well (thus, low death toll) and other things exceptionally badly (that subtitle about losing the race is about the delays in securing vaccines – and the economic nationalism of trying to promote Australian-produced options – and in moving away from exclusive reliance on lab-processed PCR tests and authorising/enabling extensive use of RAT tests). But then their claim in the concluding chapter is “overall, Australia’s handling of the pandemic was exceptionally good”, notwithstanding their claim earlier in the book that the vaccine delay – similar to New Zealand’s – was “almost surely the single most costly economic event in Australian history”, a claim which itself makes no sense unless they are using some exceptionally narrow definition of “economic event” that isn’t hinted at in the text. And they give very little attention to the Reserve Bank of Australia’s role in pandemic economic management – none at all to the massive losses to taxpayers from ill-judged risky interventions in the bond market, and very little to the worst outbreak of (core) inflation in decades.

My own final take on that “overall exceptionally good” claim was as follows:

In some respects (including the important mortality one) Australia did materially better than most. Arguably the Australian government (like New Zealand’s) got one really big call right (the initial closing of the borders in March 2020 just in time, albeit – and as [the authors] note – later than they should have). Beyond that, the record is really rather mixed. Some of that might perhaps have been inevitable in such exceptional times. But plenty of things could have been done better, as even [the authors] (sometimes grudgingly) acknowledge.

For those tempted to buy the book, if you followed events closely over 2020 to 2022 you aren’t likely to find anything new, and some of the argumentation is moderately detailed, and thus it isn’t entirely clear who the target audience was. But time moves on, people forget too quickly, and before long there will cohorts of policy advisers and even politicians for whom the pandemic period was little more than a hazy teenage memory. For them, perhaps in particular, it is likely to be a useful point of reference.

The editor of the New Zealand economics journal, New Zealand Economic Papers, invited me to write a review of the Hamilton and Holden book, which was published on their website a few weeks ago.

There were a few changes before the final published version but what follows has all the substance.

Review of Steven Hamilton and Richard Holden, Australia’s pandemic exceptionalism:how we crushed the curve but lost the race, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2024, 240pp

Introduction

No one can doubt that 2020 and 2021 were exceptional. COVID-19 was the worst pandemic in a century, and the nature and scale of the policy responses were pretty much without precedent. Those of us who’d assiduously read accounts of the 1918/19 flu pandemic got little real help in what to expect. The discontinuities in the economic data will probably be puzzling students a century hence.

But in their new book two Australian academic economists, Steven Hamilton (George Washington University) and Richard Holden (University of New South Wales), seek to highlight what they believe to have been exceptional about the specific Australian experiences and policy responses – exceptionally good (the economics), and exceptionally bad (sluggish acquisition of vaccines, very slow adoption of RAT tests). Since the overall experience of the pandemic in Australia – policy and outcomes – was very similar to that of New Zealand many of the arguments made are likely to be valid, or not, for New Zealand too.

Both Hamilton and Holden (hereafter HH) had many things to say during the pandemic, and a fair number of the points they were making then were fundamentally correct. And so if the book often has a self-congratulatory tone (and Hamilton acknowledges his tendencies in his Foreword) it isn’t entirely unwarranted.

Judged by deaths from Covid, Australia was one of the group of the best performing advanced countries. As HH recognise, these outcomes were a mix of luck and policy – Italy, for example, felt the full force of the outbreak early, but it could have been any other country, particularly those with lots of travel to and from China.

Using Our World in Data, here are the advanced countries with cumulative death rates less than 1000 per million people (a longer list than you might get the impression of from reading the book).

| COVID-19 death rates per million (to 21 January 2025) | |

| Australia | 963 |

| Iceland | 489 |

| Japan | 597 |

| Korea | 693 |

| New Zealand | 879 |

| Singapore | 358 |

| Taiwan | 739 |

In contrast there are the United Kingdom (3404), the United States (3548), and Italy (3344), with a number of central and eastern European EU countries materially higher again.

But how should we assess the wider policy response, in particular the economic side of things?

Assessing policy responses

The authors were among the organisers of an open letter in April 2020, signed by 265 Australian economists, arguing in support of government policy, including lockdowns, and they continue to champion the view that there was no trade-off between public health and economic outcomes in the peak pandemic period. It is a set of arguments that, taken together, never seemed fully persuasive.

HH remind readers of the Goolsbee and Syverson (2021) paper that suggested quite early on, using mobile phone data, that almost 90 per cent of the reduction in movement in the United States was voluntary (was happening anyway independent of legal restrictions being imposed). If so, and given that the legitimate public health goal was to get and keep the replication rate below 1 (ie each case passing Covid on to, on average, less than one other person), was there really a compelling case – that would pass a robust cost-benefit test – for fairly extreme lockdowns? How much difference did the marginal movement restrictions produce (on the health side) and at what economic and social cost? Presumably, on average, the least costly and disruptive reductions in movement occurred first and voluntarily?

Unfortunately, we do not know with any confidence the answers to questions like these. There was little or no evidence of serious cost-benefit analysis being deployed, even in principle, in the New Zealand official advice (and the Productivity Commission ran into significant blowback when it attempted something illustrative) and nothing in HH’s book suggests things were any different in Australia. Unfortunately, there is also no sign of any marginal analysis in this book (or in other post-event evaluations).

Peak lockdowns in New Zealand were more onerous than those (on average across states) in Australia and, for what it is worth, the best estimates of June quarter 2020 GDP in both countries show a materially larger fall in New Zealand than in Australia[1]. Lockdowns were not the biggest part of the economic story, but it is also very unlikely they made only a small difference[2]. Output not generated in one quarter isn’t typically replaced with additional output later, even when there is a very quick recovery in activity to the pre-crisis level. And beyond GDP effects, HH seem largely unbothered by the human costs of the more extreme provisions – funerals couldn’t be held, the dying or bereaved couldn’t be comforted, and so on. Decisionmakers, of course, had to operate under considerable time pressure in early 2020 – although as HH note, they were often slow to grasp the seriousness of what was emerging and so lost valuable time for reflection and analysis.

Hamilton was among those making the case fairly early that in a shock of this sort (not having its roots in initial economic imbalances) fiscal support measures should focus not just on income support but on keeping firms and employment relationships (and the embedded firm specific capital) intact. It wasn’t a new idea (and New Zealand governments had used that model on a small scale in the wake of the Christchurch and Kaikoura earthquakes) but as the magnitude of the Covid crisis belatedly became apparent the scale of any such support (not just dollars but the administrative capacity required) was daunting.

The United States serves as a foil throughout the book to help make the authors’ case for Australian exceptionalism (especially on the economic side of things). The authors correctly note that the American political system (in which the head of government doesn’t control the legislature, and where a large proportion of powers – including around unemployment insurance – operate at the state level anyway) could not realistically have been expected to generate quick and comprehensive whole of government responses, of the sort we saw in Australia and New Zealand. They contrast particularly the Australian JobKeeper programme programme (somewhat similar to the New Zealand wage subsidy scheme, both emphasising retention of existing employment relationships) with the US support programmes (lump sum household grants and the Paycheck Protection Programme).

The way government support programmes were designed is generally recognised as having had substantial implications for the extent to which the reported unemployment rate rose in different countries.

Increase in unemployment rate: end-2019 to peak COVID level (percentage points)

Australia +2.5

New Zealand +1.1

Canada +8.1

United States +11.3

United Kingdom +1.4

Those are stark differences[3], and HH attempt to connect the difference between the US and Australian unemployment numbers to subsequent economic performance. Somewhat surprisingly they do this wholly by reference to the employment to population ratio, which is higher now in Australia (and New Zealand) than pre-COVID, but is lower in the United States, with the suggestion that the JobKeeper type of programme, if not perfect, was better suited to a full and quick rebound in the economy.

As it happens, the United Kingdom (with a very small increase in the unemployment rate) also now has a lower than pre-COVID employment to population ratio, but more importantly there is no mention at all of the respective GDP experiences.

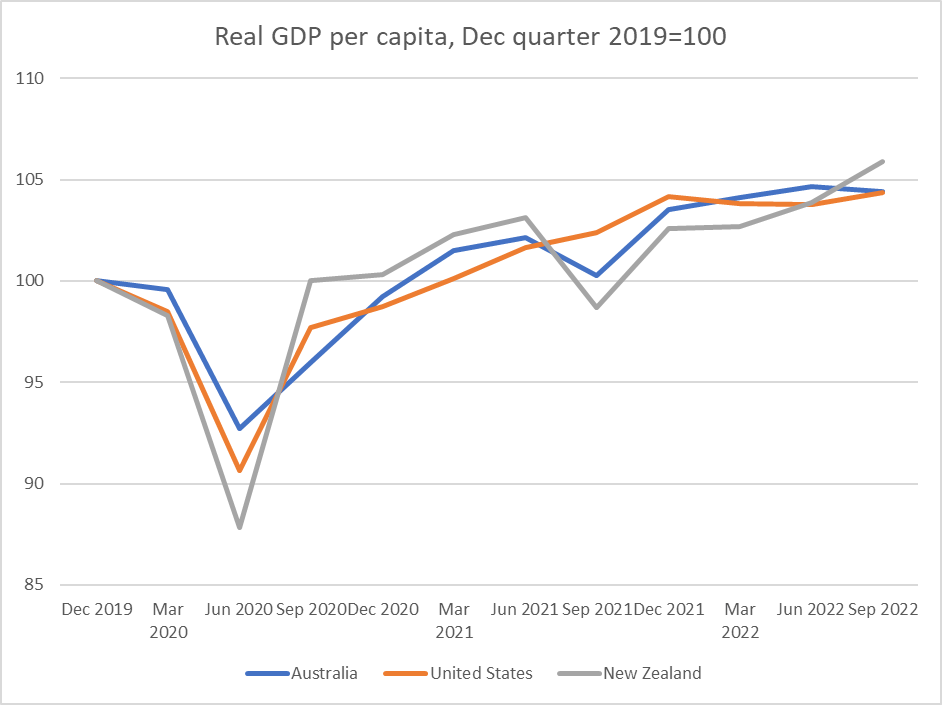

In fact, despite the very different pandemic experiences of Australia and the United States the tracks for real GDP per capita were remarkably similar. Both countries regained the December 2019 level in the same quarter (March 2021) and by the end of the immediate pandemic period the cumulative growth rates had been almost identical.

Since then, of course, US productivity and real GDP per capita growth have diverged (favourably) from those of almost all other advanced economies. The reasons aren’t yet well understood, but there isn’t much evidence that pandemic-related labour market scarring has mattered much at least at an economywide level.

As the authors highlight, Australia could reasonably be considered to have done exceptionally badly around vaccine procurement, and the approval and widespread use of RAT rest. They both devoted many column inches at the time to the breathtaking failure of politicians and officials in Australia to act early and decisively to secure access to vaccines by placing orders or buying options at scale on all the emerging potential vaccines (a New Zealand book would have to grapple with the same failure). No one knew which would emerge as best or be available earliest, and the cost of over-ordering would have been small compared to the costs of additional economic and social disruption if the population remained largely with access to an effective vaccine. The complacency – in the then Prime Minister’s words “this is not a race” – reflects very poorly on ministers and officials, and came at a considerable economic cost. Like New Zealand, Australia eventually achieved very high vaccination rates, but the operative word is “eventually”.

Unfortunately, and inexcusable as those delays were, this is one of a number of places where HH lapse into overstatement. They estimate that the vaccine delays cost Australia (directly and indirectly) A$50 billion and go on to claim that this meant that “Australia’s great vaccine debacle [was] almost surely the single most costly economic event in Australian history”. $A50 billion is a lot of lost output but it was about 2.5 per cent of one year’s GDP. By contrast, during the Great Depression Australia’s per capita GDP averaged almost 15 per cent below pre-Depression levels for five years (so in total something like 75 per cent of one year’s GDP), and the 1890s financial crisis (when it took 15 years for real GDP per capita to regain pre-crisis levels) was even worse. If one wants more recent, and directly policy-related, costly economic choices, one might think of the post-war tariff walls or letting inflation get away in the 1970s.

Macroeconomic policy

HH are firm champions of fiscal policy as a countercyclical stabilisation tool, and spend quite a bit of space in the book revisiting arguments for why there should have been (but wasn’t) countercyclical fiscal stimulus in Australia’s 1991 recession and why they believe such stimulus was both desirable and successful in 2008/09. They are sympathetic to Claudia Sahm’s proposal for additional semi-automatic fiscal stabilisers. I’m sceptical on all three counts (including the associated claim that Australia avoided a recession in 2008/09, when the unemployment rose by 1.7 percentage points and real per capita national disposable income measures fell materially), but the connection to an event like the pandemic is not clear.

In a typical unexpected downturn countercyclical policy aims to stimulate business and household demand and spending. The relative merits of monetary and fiscal policy tools can be debated but the goal is pretty clear. The goal in March 2020 was quite different. The aim wasn’t to stimulate demand or activity, but to tide people and firms over while the economy was more or less shutdown (more or less as a policy goal, through some mix of official edicts and private risk-averse behaviour). That required direct transfers in one form or another, something monetary policy simply cannot do. The fact that programmes like JobKeeper (and the New Zealand wage subsidy) worked – at vast, probably unnecessarily large, fiscal cost[4] – in a unique crisis like COVID tells us almost nothing about how best to handle future conventional (aggregate demand shock) downturns. And nor do the experiences of past conventional recessions shed useful light on how best to handle shutting down much of the economy temporarily for non-economic reasons.

One of the striking omissions in the book is any serious or sustained discussion of monetary policy and the performance of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). Monetary policy wasn’t the instrument that could or should have dealt with the income support and firm-retention goals governments rightly had through COVID. But monetary policy moves last, and is supposed to take into account all the other pressures on the aggregate demand/supply balances, with the aim of keeping inflation near target. Faced with the unique pressures of COVID too many central banks, including the RBA, failed badly. Core inflation reached levels it was never supposed to reach again under inflation targeting. And those same central banks ran up massive losses (tens of billions of dollars in the RBA case) on ill-judged and largely ineffective bond buying programmes. These massive losses to taxpayers are not mentioned at all in the book.

There is a brief discussion of inflation, but HH seem to treat those outcomes as just a price that had to be paid, even describing the inflation (somewhat curiously) as an “insurance premium” (such premia are usually fixed upfront against uncertain losses and are not the unexpected outcome). They, like many central bankers (at least judging by their public remarks), seem utterly indifferent to the huge redistributions of wealth such a severe outbreak of unexpected inflation caused.

Various commentators, including HH, contrast the really gloomy macro forecasts that were widespread in mid-2020 with the actual outcomes. The suggestion is that this is a testimony to policy effectiveness, but surely it is mostly a testimony to forecasting failure? Central banks and finance ministries in the second and third quarters of 2020 knew all about the nature and magnitude of the policy support, but they simply misread the overall macroeconomic implications. Take the RBA Statement of Monetary Policy from as late as November 2020: they forecast trimmed mean inflation at 1 per cent for 2021 and 1.5 per cent for 2022, both well below target. Projections of that sort at that time were not uncommon (those of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand were similarly weak). Those serious misjudgements, not the COVID support interventions themselves, gave us the serious inflation problem that central banks are still now dealing with the after-effects of. Getting the balance between demand and supply effects right, knowing what weight (little, as it turned out) to put on adverse uncertainty effects etc, wasn’t easy, but it was the job central bank experts are paid to do.

Conclusion

Much is made by HH of Australian “state capacity”[5] and at one point they suggest that “if this book is about anything, it’s state capacity”. On recent metrics (eg O’Reilly and Murphy (2022)) state capacity in Australia going into the pandemic was good but didn’t stand out relative to other advanced economies. The authors are clearly right to praise the ability of the Australian Tax Office (ATO) to put in place quickly the JobKeeper programme, itself in part a reflection of efforts to modernise the agency over previous years. But since state capacity is more than just the technical abililty to implement a programme quickly and efficiently under pressure, we can’t – and HH don’t – ignore things like the vaccine procurement and RAT approval issues, both of which were costly failures. And what we saw, in Australia no more or less than most other advanced countries, was monetary policy authorities failing to do their core job adequately when it really counted.

We need many more books and formal studies about all aspects of the pandemic period, national and cross-country. That said, it isn’t entirely clear who the target market for this particular book is. The Australian Treasury (past and present), the ATO, and the then Treasurer Josh Frydenberg will welcome it (they count as the authors’ heroes), and those already inclined to agree with the authors will nod along as they read, but without necessarily learning anything new. In a fairly short account covering a substantial amount of sometimes-complex historical ground perhaps there isn’t room for, and they don’t attempt, fresh in-depth analysis. But memories fade all too quickly, and before long a new generation of junior policy analysts will be staffing agencies with only a hazy child’s memory of the pandemic. The book should be a useful introduction to much[6] about the Australian government response.

Which brings us to the final issue: was Australia’s overall handling of the pandemic “exceptionally good”, as the authors claim? In some respects (including the important mortality one) Australia did materially better than most. Arguably the Australian government (like New Zealand’s) got one really big call right (the initial closing of the borders in March 2020 just in time, albeit – and as HH note – later than they should have). Beyond that, the record was really rather mixed. Some of that might perhaps have been inevitable in such exceptional times. But plenty of things could have been better, as even HH (sometimes grudgingly) acknowledge.

References

Gibson, J. (2022), Government mandated lockdowns do not reduce Covid-19 deaths: implications for evaluating the stringent New Zealand response, New Zealand Economic Papers Vol 56 2022 Issue 1

Goolsbee, A. and Syverson, S. (2021), Fear, lockdown, and diversion: Comparing drivers of pandemic economic decline 2020, Journal of Public Economics 193

O’Reilly, C. and Murphy, R. H., (2022), An Index Measuring State Capacity, 1789–2018, Economica, Vol 89, Issue 355 pp 713-745

Reddell, M., “A radical macro framework for the next year or two”, Croaking Cassandra blog, 16 March 2020 (https://croakingcassandra.com/2020/03/16/a-radical-macro-framework-for-the-next-year-or-two/)

[1] Note, however, that measurement of a locked-down economy was much more difficult than usual, particularly in non-market sectors, and outsiders can’t be sure how comparable the (inevitable) assumptions used were.

[2] John Gibson (2022), written in 2020, is also relevant here, drawing on the diverse restrictions in the different parts of the United States..

[3] The United Kingdom had by far the largest peak to trough fall in GDP of any of these countries.

[4] HH tend to play down the validity of ex post observations of this sort (while accepting that there may be cheaper options that could be considered in future), but as it happened I had laid out before the New Zealand lockdown the genesis of an alternative approach that, had it been adopted, would have proved considerably cheaper (Reddell (2020)),

[5] For example (p39), “the sharp contrast with the United States revealed deep reserves of state capacity that we simply had not realised were there”.

[6] But not all. One notable omission from the book was much discussion about the range of different state approaches.