Opening The Post on Monday morning it was as if the 2026 election campaign had gotten underway already, even as we sit waiting for the new government to form.

Under the headline “An answer to National’s revenue gap” was a column by the CTU economist, and former Grant Robertson adviser, Craig Renney suggesting that National should scrap most everything it campaigned on and adopt instead a left-wing tax policy approach that was not acceptable even to the Hipkins Labour Party this year. But then we learned last week that Labour itself was putting all revenue options back on the table as it thinks about its own future. One media profile last year suggested that Renney is keen on getting into Parliament, and to be fair you’d have to acknowledge that he was a more high profile, perhaps even effective, campaigner this year than most Cabinet ministers.

Anyway, Renney’s idea is that we should look to the United Nations for guidance on tax policy (why?). Some United Nations report apparently mentions windfall profits taxes, and the number of them introduced in various European countries last year and this.

Renney quotes this UN report saying “several developed countries introduced taxes aimed at ensuring a fair distribution of profits in industries that have experienced significant gains because of the pandemic and financing recovery programmes, or subsidies for energy consumers”.

And then he leaps into claiming the relevance of this to New Zealand. Where does he start? With, of all companies, Air New Zealand (“Last year, Air New Zealand’s profit was up 180%.”)

We are seriously supposed to believe that Air New Zealand experienced significant gains because of the pandemic? The company that only survived on government handouts and recapitalisations after its business dropped away very very sharply, through the mix of closed borders and individual reluctance to travel? The company that lost $454 million in the year to June 2020, lost $289 million in the year to June 2021, and lost $591 million in the year to June 2022, before recovering to make $412 milllion in the year to June 2023. Shareholders – the largest of which is the government itself – simply lost truckloads of money from owning an airline through a pandemic. As you might expect. But Renney apparently thinks them a serious candidate for a windfall profits tax….

Another extraordinary feature of his article is that as he talks up European governments imposing windfall profits taxes he never once mentions that the overwhelming bulk of such taxes were imposed on fuel companies in the wake of the sanctions the EU (and a bunch of other countries) put on Russian gas and oil exports after the invasion of Ukraine, which had the effect of driving European gas prices, and thus marginal wholesale power prices sky high. There is perhaps a certain logic in governments that make a product artificially scarce (in pursuit of admirable geopolitical ends) also taxing what might be genuinely windfall gains. One might haggle over how such taxes were imposed etc (there is good reason to think many were ill-designed if they were really supposed to be windfall taxes), but the basic idea isn’t prima facie absurd.

(If you want an accessible summary of what the Europeans have been doing, try this recent report.)

But……New Zealand wasn’t directly affected by those sky-high gas prices (one reason why headline here never went as high as it did in many European countries, including the UK). It doesn’t stop Renney of course (writing of New Zealand, “the top four energy companies made $2.7 billion in operating profits, or $7.4 milllion profit per day”, without any sense of context or scale (return on equity eg) or any sense at all of there being anything ‘windfall’ at all about those profits).

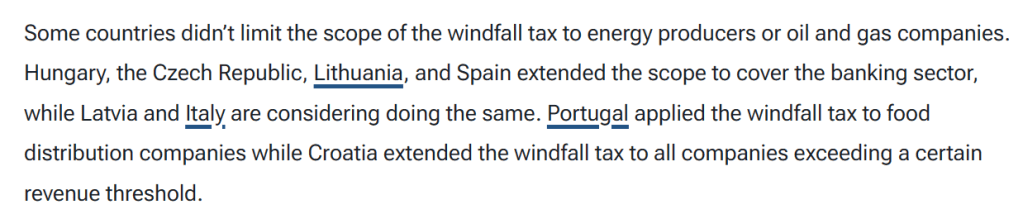

How wide-ranging are those European taxes?

Renney tries to tell us that “globally, these taxes were aimed at……markets where there is little competition (such as supermarkets)”, but in fact that seems to be a sample of one country with a tax on supermarket-type entities (itself done in a distortionary manner to apply only to big companies), in one of Europe’s less-than-stellar economies. As that clip above says, Croatia introduced one (not really focused on true “windfalls” at all), imposed for a single year on all big companies (200 or so). Much of the focus of these measures was to pay for big consumer energy subsidies, in the face of that same energy price shock induced by the sanctions. None of which has any relevance to New Zealand, or to any sort of medium-term revenue strategy. And we know people think New Zealand supermarkets make “too much” money, but whatever the merits of that argument it has nothing to do with any serious analysis of a case for windfall profits taxes. (As it happens, I thought there might have been an arguable in-principle case in respect of the profits supermarkets were given by the government when it forced almost all other food retailers to close during lockdowns, channelling all business to the supermarkets………but I guess that rather arbitrary distortion was done on Renney’s own watch as adviser to the Minister of Finance.)

Ah, but then there are the banks, bete noire of the New Zealand left (whether they really dislike the banks or simply find them a convenient populist whipping boy is never quite clear). As that clip above noted, a handful of European countries had imposed “windfall” profits taxes on banks (whatever Italy was first proposing was substantially watered down). I didn’t look up all those cases, but I had a look at Hungary – a government that of course the left usually looks utterly askance at – where the so-called windfall profits tax isn’t even based on profits, or any credible sense of identifiable windfall – it is just a crude tax grab based on revenue (not profits) and this year was sharply modified through further financial repression – banks could avoid much of the tax if only they bought more government bonds.

But what of New Zealand and the banks operating here? We know Renney’s old boss the (still) Minister of Finance got tantalised a year ago by the idea, before being eventually talked out of it.

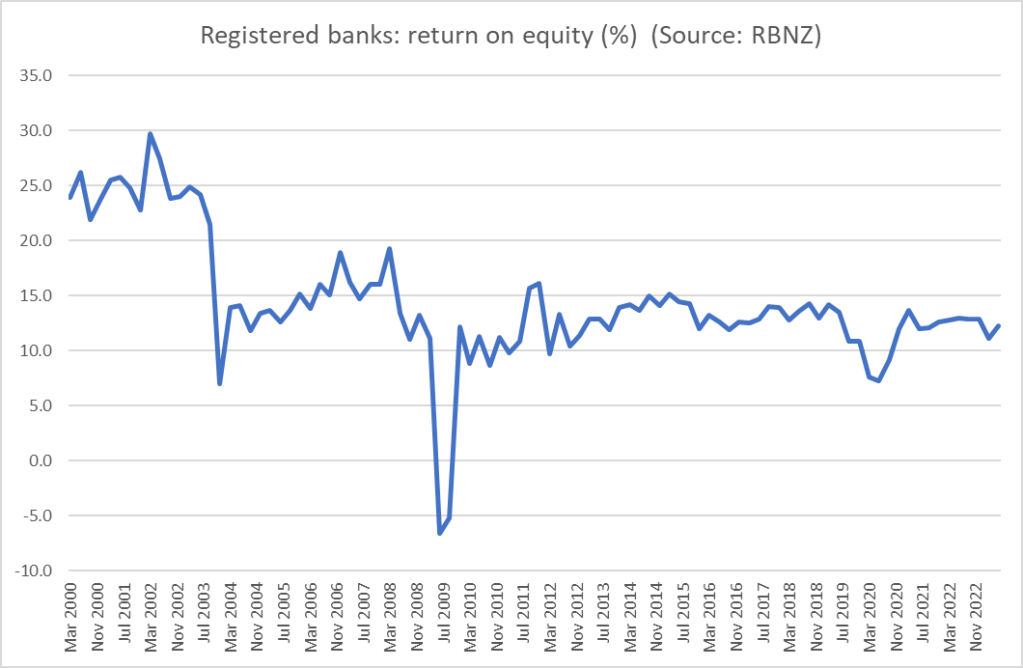

And as for the data

there is simply no evidence of a pandemic or post-pandemic windfall for banks. If anything, return on equity has been trending downwards (as you’d expect in the face of higher capital ratios), and if you really think there are important barriers to entry etc, tackle those directly. Your party was, after all, the government for the last six years.

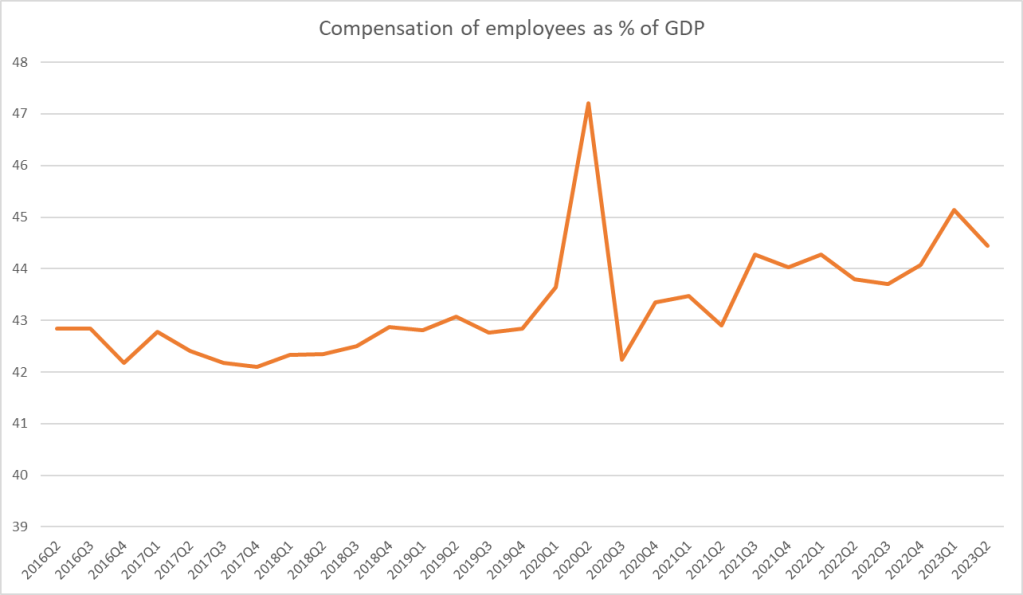

As for those rapacious businesses more generally……well, workers have had an increased share of GDP over the last couple of years (as you might expect in an badly overheated labour market).

Renney goes on to claim “perhaps the most compelling case for their use comes from the fact that many of the countries that have launched windfall taxes now have lower levels of inflation than New Zealand”. That isn’t even a serious attempt at economic or policy analysis (let alone something warranting “the most compelling case”, unless Renney is conceding that the actual substantive case is threadbare). Of course, if you use big direct subsidies to consumers you can lower headline inflation – Renney’s Labour government did that for a year with the petrol excise tax cut, without even suggesting a way to pay for that largesse – and many of these European so-called windfall taxes have been mostly about financing such subsidies. What matters macroeconomically is much more about measures of core inflation.

We could check out some of those countries that did more than just energy taxes, except that almost all of them are in the euro, where monetary policy is set for the region as a whole (Germany by far the biggest economy). And of the two that aren’t, Hungary had core inflation in the year to September of 12.8 per cent and the Czech Republic had 7.1 per cent core inflation in the same period.

In his final paragraph, Renney comes back to the banks – the honeypot the left keeps eyeing up. There he writes that “I’m confident that the current chairs of the big four banks wouldn’t mind a phone call from the incoming prime minister asking for their cash.” Perhaps that is supposed to be a dig at the overly close relationship between the incoming PM and the chair of the New Zealand ANZ subsidiary, but I think it is pretty safe to say that all the chairs (and the CEs) would tell the PM that they’d pay what the law demands, not a penny more or a penny less (the approach most of us take), and if somehow they were personally inclined to be more generous, they’d no doubt find their parent boards in Sydney and Melbourne, let alone shareholders around the world, not exactly impressed at scheme to give away shareholders’ money. Such a chair might not, and probably should not, last long.

What is quite extraordinary in the whole column is that there is not even a hint (and sure there are word limits, but you can squeeze in hints about things that might really matter) that we already have one of the highest company tax rates in the advanced world, and have historically had low rates of business investment. Arbitrary extra business taxes – with not a even a hint of symmetry (windfall refunds/handouts in tough times) – are not exactly a standard feature of prescriptions for prosperity. But then in six years in government (in three of which Renney was the key adviser to the Minister of Finance), Labour showed little or no interest in lifting productivity or longer term economic performance, just in redistributing the pie differently and channelling a larger share of GDP through the government’s book, often not even funded by tax revenue. Renney’s prescription boils down to the new National-led government doing more of the same. Low as my expectations of that government are, at least on Renney’s specific schemes (lots more business taxes, lots more subsidies) I don’t worry too much.