In the years after the financial crises of 2008/09 one often read plaintive cries of “and who went to prison?”, and angry claims that the system was rigged. I can’t say that I was ever much moved by such lines. We simply don’t – or shouldn’t – generally imprison people for being bad at the business they are in, whether it is banking or baking, even if the businesses themselves were big, and the people concerned had employers who’d previously paid them lots (and lots) of money.

There has been a plethora of books about aspects of that crisis period. Glancing along my bookshelves just now I counted 100 or more, most of which I’ve read. Some were very analytical, some were lively descriptions of some aspect or other of that period, some country-specific, some more general, some were more about policy and policy institutions, some more about bankers and financial markets, but not one of them disconcerted me (and that is putting it very mildly) in the way that Rigged, a new book by BBC economics correspondent Andrew Verity did. (Amazon Australia shows the publication date as 1 August 2023, but I ordered it and it arrived a few days ago). It is a simply astonishing story, which shows a whole set of authorities (notably the British ones) in a very very bad light.

The context is the so-called “LIBOR crisis”. For readers who followed that story over the last decade, much of what follows won’t be new, especially if you’ve been in the UK. But I hadn’t really, because it seemed to be mostly a moral/political panic, in the “why aren’t evil bankers in prison?” vein. And, to be honest, from what little I had read of the story, I knew that I’d observed stuff in the little New Zealand markets in my years in the Reserve Bank’s Financial Markets Department that, if you were concerned about this sort of thing, was arguably more egregious.

LIBOR is (or was) the “London Interbank Offer Rate” (there was also LIBID – “bid” – although I don’t think it gets a mention in the book). It was a major set of benchmark short term interest rates, in various currencies, off which many other contracts are priced. LIBOR rates were set each morning – under the auspices of the British Bankers’ Association (BBA) – when cash dealers in each of 16 banks would indicate (for each currency and term)

“At what rate could you borrow [unsecured] funds, were you to do so [in the London market] by asking for and then accepting inter-bank offers in a reasonable market size just prior to 11 am?”

The submissions would be ranked, with the top and bottom four excluded and the remaining eight averaged. Individual banks’ experiences could be expected to differ a bit (although not by much in normal times), and for any individual dealer answering the question there might be a (tightly-bunched) range of possibilities. It was an estimate, informed usually by data in fairly liquid markets, with the exclusion and averaging rules dealing with outliers and, thus, typically expected to result in a reasonable central estimate. Very short-term rates would typically be very close to the relevant central bank’s policy rate. Within each bank, there was often a bit of jockeying: other dealers might have positions that would benefit a little from that day’s LIBOR rate being just a bit higher or a bit lower, but since the cash dealer had to lodge a response at which his (they were almost all male at the time) bank could borrow, any leeway was apparently very slight, perhaps one basis point, occasionally two.

And so it had gone on for a couple of decades. Regulators knew how the system worked, the adminstrators (BBA) knew how the system worked, as did participants in the markets.

But then the financial crisis began to build in the second half of 2007 (the crisis period is often dated from 9 August that year, the Northern Rock crisis became public in early September 2007). Short-term interbank funding markets were no longer as liquid as they had been and material gaps started to open up between where banks would lend to each other unsecured and the central bank policy rates (either for fully collateralised lending or risk-free deposits at the central bank itself). And there were swirling differences in market and media perceptions of which banks might be a bit less sound than others.

You might have hoped that each bank’s dealer would simply continue to submit each day his best estimate of what his bank could borrow at unsecured and let things fall where they may. But that didn’t happen. Instead it became something of a “dirty secret” (except not very secret at all since people in banks and markets knew it, as did the key regulatory bodies, and there were even stories in the major financial newspapers) that the published LIBOR rates no longer represented a best estimate of what individual banks (or the sector as a whole) could borrow from each other at. Verity focuses in on Barclays, where the cash dealer seems to have tried quite vigorously to follow the rules, which resulted in Barclays posting rates above those of the rest of the panel of banks, which (submissions being visible to others) in turn prompted concerns “if they are having to pay that much they must be in more trouble”, and even a sell-off in the share price. And so the pressure came on the dealer from above to bring his submissions more into line with those of the other banks. He, rather grudgingly (documenting his concerns and uttering them to anyone who would listen), went along. Regulators and central banks on both sides of the Atlantic were aware of what was going on, and if anything seem to have been more sympathetic to Barclays than (say) concerned that posted rates (used as benchmark pricing across the system) no longer reflected real borrowing costs.

As the financial crisis intensified so did the problems (some quite practical, in that at times the markets had frozen so badly that really no bank could borrow unsecured from others, so in truth there probably should have been no LIBOR rate at all). The gaps between unsecured interbank rates (both “true” rates and published LIBOR rates) and policy rates was high and widening, at times when central banks – in the UK, but in most other countries – were cutting policy rates deeply to try to lean against the collapse in demand and economic activity. Market rates often weren’t coming down much (in some cases they were rising) and politicians and their advisers were often getting increasingly uneasy.

And so the pressure – and this is extremely well-documented in the book – came on banks to put in lower LIBOR submissions. Doing so wouldn’t change actual borrowing rates – either interbank or the retail rates that the wholesale rates influenced – but I guess it was going to get better headlines, and it might make it “look” like things (policy responses) were “working”. In the UK case (the focus of the book), this involved not just very senior figures at the Bank of England, but them channelling pressure from The Treasury and Downing St itself (people named include very senior and otherwise respected figures, including a current Deputy Governor of the Bank of England, and someone who was until last year the permanent head of The Treasury in the UK). Very senior bankers were left in no doubt that the authorities wanted the LIBOR rates marked down, and they complied, ordering their underlings (the cash dealers and their immediate bosses) to bring LIBOR submissions more into line. The differences here were not a matter of a basis point or two, but often 50 basis points or more. Relative to the LIBOR rules, anyone with a contract in which they received the LIBOR rate was, in effect, being bilked out of a lot of money (vice versa if you were paying LIBOR). One could, of course, argue, that central banks were actively trying to lower short-term rates generally by a lot, but…….acceptable instruments don’t generally include pressuring bankers to write down numbers that simply don’t reflect reality. If central banks really wanted market rates even lower, they had tools available to make that happen directly.

The more pragmatic and less idealistic of you may here be drumming your fingers and going “needs must”, and in a crisis what needs to be done gets done. I wouldn’t agree with you – institutions are supposed to be built for resilience under stress, not for fair weather events only – but if that was the end of the story, it would have been quickly lost to history.

But it wasn’t the end of the story.

As the crisis faded, in some circles the narrative that someone “needed to pay” took hold. At least in the UK, as I read the book, there wasn’t much interest in pursuing anything around LIBOR, until the Americans got involved. You might reasonably wonder what the activities of British officials in Britain and British employees of British banks in Britain, as regards a benchmark rate owned and administered by a British entity (the BBA) had to do with the US, and its Department of Justice and CFTC. They seem like good questions, but such is the world as it is, and the trans-national overreach of the US on matter financial. As Verity tells it, Obama’s nominee for head of the CFTC had had close ties to Wall St and wasn’t going to get confirmed by the Democrat-controlled Senate unless he was going to take a credible stance as an avenging angel of wrath.

My interest is less in the US side of things than in the UK, where (thanks to leaks in particular) the book is astonishingly well-documented. Anyway, the US started pursuing banks abroad (Barclays in particular in this book), in what seems like a bizarre process in which they relied on the banks themselves to search their own documents, and then negotiated (large) administrative fines, which saved the banks and their CEOs and chairs, all while throwing under the bus a few fairly junior employees who’d initially been more or less compelled to talk to the US authorities, thinking of themselves as expert witnesses etc, only to find themselves personally in the gun,

These employees became alert to the prospect of spending much of the rest of their lives in a US prison, (having regard to the very low acquittal rate in US courts) for things they were quite sure they had never done, except as normal, accepted commercial practice, well known to central banks and regulatory agencies on both sides of the Atlantic, typically either authorised or instructed by senior managers within their own banks. And so several became convinced their only option was to get themselves charged in the UK, preferably engaging in a plea deal that might involve, to all intents and purposes, lying to conform with the preferred narrative of the UK authorities, to get to stay in the UK and not destroy themselves and their families financially. Others preferred to defend themselves in the UK, several were charged in the US (before US courts finally overturned the very basis on which they had been charged).

And, to be quite clear here, none of all this regulatory and legal action involved anything that had gone on during the financial crisis (when not only had authorities, notably the Bank of England, been aware of how the system worked, they had actually been part of engineering LIBOR submissions a long way from actual market rates). Instead, the bounds of interest were very carefully drawn to cover only the period prior to the crisis beginning to unfold. The focus was on how these dealers had lodged their LIBOR submissions in normal times, as many many like them had done for a couple of decades. The focus was on other people in each bank suggesting to the dealer that their positions might benefit from a slightly higher or slightly lower LIBOR (the basis point or two mentioned above, in reaching a necessarily imprecise estimate).

And what was the offence? Well, there was none in statutory law. None.

Instead, the authorities wheeled out an old common law offence “conspiracy to defraud”, which – at least as Verity tells it – was so little regarded by the UK commercial barristers prior to the crisis that there had been a push to remove it. Under these provisions/precedents, there was no need to show that anyone had lost, or to quantify any losses. And yet the political rhetoric was all about egregious rip-offs, suffering customers, and rigged markets. Judges ruled – without allowing appeal – that it was enough that someone in a bank had suggested to the bank’s cash dealer that his/her positions might benefit from a slightly lower/higher LIBOR and the dealer to say something like he’d see what he could do. There was – according to English justice- a conspiracy to defraud – all recorded in emails and trading room recorded phone calls. The same judges then refused to allow testimony from expert witnesses as to how markets actually worked (in one case regarding EURIBOR submissions, the UK judge refused to allow testimony from the people who had written the code of conduct around the operation of EURIBOR).

Here, some scale and perspective is worth noting. As I noted above, LIBOR worked with a panel of 16 banks, with the four highest and four lowest for any particular currency/term on the day excluded. If perhaps a dealer in one bank had shaded his bank’s estimates 1 basis point in one direction (remember that plausible range was typically not much more than a couple of basis points), then even assuming there was not some other bank with exactly the opposite interest, the chance of affecting LIBOR at all was low, and the magnitude of any plausible effect tiny. There are hard numbers at places in the book.

By contrast, the activities during the financial crisis period, done in full awareness and often with the encouragement of the authorities and of specific named very senior bankers, never saw judicial scrutiny.

And so eight bankers – cash dealers – went to prison in the UK, serving non-trivial custodial sentences, for offences that no one thought were offences until the “avenging angel” mood took hold in the wake of the crisis. And when I say “no one” here I mean not just the dealers, but their bosses, their bosses’ bosses (the chief executives of the banks were the board of the BBA which administered LIBOR), and the central banks and regulatory authorities on both sides of the Atlantic, but particularly (and at very senior levels) the Bank of England. Not one Bank of England official rang the police (or SFO) at any point to express concern at the normal commercial way they knew the market worked, and those senior people are on record during the crisis encouraging/abetting/ (perhaps) instructing, bankers to deviate from the LIBOR rules, including passing on the political pressure from Downing St (which was no part of any central banker’s mandate).

And yet, as Verity records, in 2015 at the height of the hysteria – and amid the criminal trials – the then Governor of the Bank of England delivered a major speech in which he would “publicly demand that the government should change its sentencing guidelines to raise the maximum jail term for “rogue traders” from seven to ten years”. This was (is) the same central bank that (Verity records) “George Osborne had urged the central bank to come clean about its role in Libor, [but] the Bank of England had decided against that. Freedom of Information requests would be consistently rejected in the succeeding years”.

Your reaction might be to wonder why anyone would be particularly sympathetic to well paid (not very senior) bank traders. Because it was an egregious abuse of justice: sound process and integrity matter whether it is a scruffy teenager or a nicely-dressed multi-millionaire trader facing the system. Any of us could one day be in gunsights of the state. I mean, if one were going to (in effect) create retrospective offences and start prosecuting bankers for them mightn’t one prosecute those in charge (all the way up) who were actively aware of how things worked, authorised and rewarded people, and at times directly instructed behaviour that was egregiously distortive (in terms of LIBOR rules/practices (rather than, as in at least one case a ‘whistleblower’), and consider expert testimony from people with responsibility for overseeing the relevant markets etc.

The conduct of three lots of people in this whole affair warrant scrutiny:

- the politicians. How did Cabinet ministers stand by and allow these prosecutions and imprisonments when (if nothing else) they knew the people who managed and instructed those charged walked free, with no criminal or civil consequences whatever? And how did former PMs and Cabinet ministers (Gordon Brown, Alistair Darling – Chancellor during the crisis) never speak up and out, not just about their own roles but the disproportion of sending low level people to prison while their bosses walked free? It is the sort of act of omission that leads people to simply despise politicians,

- the senior bankers. Many despise them already, but really……..you keep your job and your bank or walk way with tens of millions in retirement packages etc, while seeing former staff – who acted on your instruction and authorisation – sent to prison, people against whom charges were laid only because you did your own searches of your own bank records, saved yourself, and tossed some staff to the criminal authorities. Just despicable. Who ordered Peter Johnson (cash dealer at Barclays) to mark down his submissions, despite Johnson’s explicit written dissent? Why, the very top tier of Barclays’ management.

- the central bankers (and the like). I expect better from central bank and Treasury officials. Not necessarily excellence or at times even basic competence, but integrity and decency. I’ve met and dealt with some of the individuals named (I recall now sitting in the Bank of England’s chief economists’ seminar in May 2008, in the early days of the crisis, listening to Sir John Gieve, deputy governor responsible for financial stability – altho, curiously, not named in the book) so perhaps it shocks me more. Perhaps one can defend the approaches senior BoE or HMT (or even Downing St) officials took during the crisis, but they actively aided (and seem to have pressured banks to facilitate) the distortion of LIBOR. I’m not suggesting any of them should have been prosecuted, but how (a) does the Bank of England justify not revealing in full its own part and knowledge during the period, all while Mark Carney as Governor was baying for the blood of traders, and b) how come that, even in retirement, not one of these people spoke out and suggested that it was simply wrong to be sending these people to prison. None of them appears to have been willing to speak to Verity, none has spoken in public, and we are left guess whether just possibly one or two might have said quietly “I say old chap, are we really sure about this?” (if so, to no apparent effect). It reflects very poorly on all involved, some of the most senior (and otherwise) respected figures in British economic and financial policy. One could see it – perhaps unfairly but it isn’t obvious what other interpretation makes sense – as circling the wagons in their own defence, and that of their peers who ran the banks. Never mind the juniors, we can destroy their lives and marriages and send them to prison. (These the same people whose own policy misjudgments – viz recent inflation (Andrew Bailey gets a couple of minor mentions in the book) – result in few/no consequences beyond gilded retirements and knighthoods or peerages.)

From the sound of the book, the English prosecutorial and judicial systems have quite a bit to answer for as well, but….I’ll leave that to the lawyers.

The whole thing smacks of a witchhunt: someone must pay, these individuals their bosses have helpfullly pointed us to are someones, so they will do (and it wouldn’t do to pursue the bosses or else, perhaps, confidence in the system might be eroded – which if true should have at very least raised questions as to whether the whole grossly-slanted chain of prosecutions, where eg juries were never allowed to know what regulators had known in advance, was being pursued for any reason other than the a politically-driven effort at distraction).

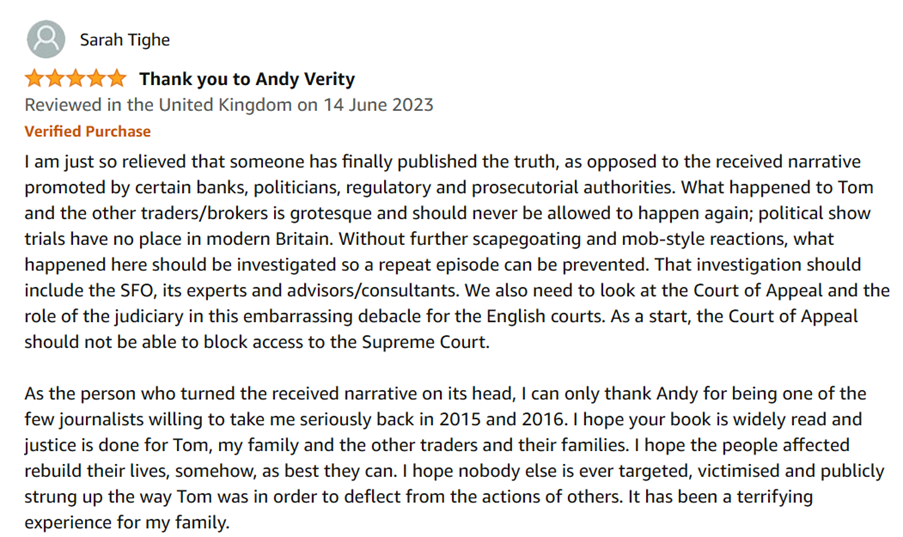

It is hard to tell if I’ve done a 325 page book justice. All I can do is to encourage people to read it. Yes, it is about technical stuff, but Verity does an impressive job of explanation and translation, and his story is supported with copious direct quotations, most of which would never have come to public light if a big dump of documents and recording had not been leaked to him. I’m going to leave you with the Amazon review comments of Sarah Tighe, herself a lawyer, ex-wife of one of those sent to prison (there is a recent extended interview with him here)

I went looking for reviews of the book, and couldn’t yet find any yet. But interest in the issue seems to be rising again in the UK (here is a recent parliamentary speech from a senior backbencher).

One fears that even if the individuals eventually have their convictions overturned (and how do you compensate someone for a life destroyed?) that officialdom in particular will never have to answer the hard questions it seems it (collectively and as accountable individuals) should.

PS Someone who isn’t named in the book, but the division he ran is, is the Reserve Bank’s Deputy Governor whose CV includes this

Now that was probably a fourth [UPDATE: or perhaps 5th1] tier position in the Bank of England, and he took this specific position up just after the worst, so he wouldn’t have been in any sort of direct decision-making role. But one is left wondering how he feels about those sent to prison while he’d been a fairly senior part of a system and institution that was encouraging banks actively to manipulate LIBOR submissions/rates. It should matter in someone who is (a) on the MPC, b) is head of financial stability here, and c) must be one of the favourites to himself be the next Governor of the Reserve Bank. There is that old line “the standard you walk by is the standard you accept”. No one should accept – or walk by – the standards of officialdom on display in this book.

- See references to Hawkesby in footnotes to the organisation chart on page 60 of this later BoE report