In my first post today, I posed some questions around the plausibility of the assumed increase in international travel into and out of New Zealand if the proposed Wellington airport runway extension was to proceed.

In this post, I want to focus mainly on how the consultants have calculated the net national benefits from the runway extension.

The Sapere cost-benefit analysis estimates net benefits to New Zealand from proceeding with the runway extension now of $2090 million (2015/16 dollars). These results are summarised in Table 30 of the report. Of these gains, just under half accrue to New Zealand users of the airport (in respect of both passenger and freight traffic) and just over half accrue to “other sections of the community”.

Even if the passenger number assumptions are correct, the benefits to New Zealand users appear to be somewhat overstated, and the benefits to the rest of the community are largely non-existent.

Take the users first. The main benefit to New Zealand users is the lower cost of travel. Much of that is the cost of time. The consultants have valued the time of New Zealand travellers using some standard values from an Australian Civil Aviation Safety Authority document, but don’t appear to have allowed for the fact that New Zealand earnings (and hence the appropriate value of time) are materially lower than those in Australia. In PPP terms, real GDP per hour worked in New Zealand is only around 75 per cent of that in Australia. That suggests the consultants have overstated the value of the time savings, and that the actual number would be lower by perhaps 25 per cent.

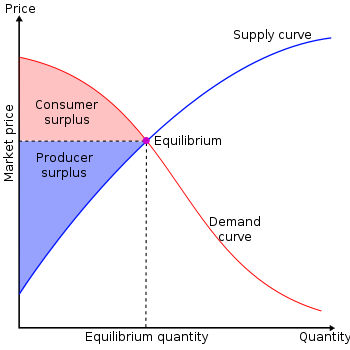

Concepts of consumer and producer surplus are very important in evaluating the welfare implications of proposals such as this. The basic idea is illustrated in this chart.

Consumer surplus is the value from consuming a product or service over and above what the consumer had to pay for it. For some consumers, the surplus will be large (think of the first refreshing drink on a very hot day), but for the last additional consumer (the marginal) consumer, that surplus should be zero. People will purchase additional products or services up to the point where the marginal cost to them is just equal to the marginal value of that additional consumption. We’ll come back to producer surplus shortly.

Sapere have allowed for an estimate of the consumer surplus that arises from the additional use of air travel services by outbound New Zealand residents ($73 million of the benefits). I’m not totally clear how they derived that benefit estimate But they consciously do not to attempt to put a value on the additional consumer surplus New Zealand residents gain from the additional goods and services consumed on their additional overseas holidays. It is hard to estimate such a value, but (as they pointed out to me) this omission does somewhat understate the benefits to New Zealanders of a runway extension that leads to the sort of increased outbound New Zealand traffic the calculations are based on. However, while this is an omission, the magnitude seems likely to be quite small. Recall that these are the marginal travellers, for whom a holiday abroad is only attractive because of the option of travelling directly through Wellington. It is also worth stressing that while these gains are real, they accrue directly to users of the airport, and provide an additional basis on which the airport could recoup the considerable cost of providing the longer runway.

The bigger questions arise around the estimates of the benefits to the rest of the community.

The first of these is the value of the additional GST on sales of goods and services to the 200000 more (by 2060) annual foreign visitors to New Zealand as a result of the runway extension. That GST is mostly a net real gain to New Zealand (foreigners funding our government spending). In the Sapere estimates, it would be worth a discounted present value of $184 million, so represents almost 10 per cent of the estimated total economic benefits.

But increased GST from foreigners spending in New Zealand is not the only GST effect likely from extending the runway. Cheaper travel also works by encouraging more New Zealanders (especially those from around Wellington) to travel abroad. When New Zealanders travel abroad they pay GST (or the equivalent) to foreign governments. And the income they spend abroad can’t subsequently be spent at home. Had they spent the same money in New Zealand, the GST would simply have been, in effect, a transfer from one set of New Zealanders to another. But with an increase in foreign travel, it is now a transfer to foreign governments. Even on the InterVISTAS/Sapere numbers, around a third of the net increase in foreign travel results from New Zealanders going abroad. If anything, I’ve suggested that long-haul flights to/from Wellington, if viable, might be more attractive to New Zealanders than to foreigners. At best, the GST gain is likely to be no more than half the Sapere number.

But much the biggest issues relate to the possibility of benefits to New Zealand from additional foreign tourists buying real goods and services in New Zealand. Sapere appear to have estimated a total for the likely increase in tourist spending in New Zealand and then subtracted an estimate for the cost of providing those services. For that they have assumed that 45.5 per cent of the expenditure is domestic value-added (ie returns to labour and capital). That approach doesn’t seem right and generates highly implausible estimates.

The producer surplus is the gain to the provider of a good or service over and above what he or she would have been willing to provide that service at (see the earlier chart). The cost of providing the service includes the cost of intermediate inputs (materials etc) but also the cost of the labour and the cost of capital (a normal rate of return). If the producer sells product at that cost, there is no producer surplus. In this context, there is no net economic benefits – economiccosts have just been covered.

Over the long haul, in reasonably competitive markets, producer surpluses should be very small (in the limit zero). For a hotel that budgeted on 80 per cent occupancy, a surprise influx of visitors for the weekend will generate a producer surplus – the windfall arrivals add much more to revenue than they do to costs of supplying the service. But over the long haul – and the airport project is evaluated over the period out to 2060 – it is fairly implausible that there will be any material producer surplus resulting from well-foreshadowed increases in visitor numbers. Most of what tourists spend money on in New Zealand are items such as accommodation, domestic travel, and food and beverage. In all those sectors, capacity is scalable. One would expect new entrants just to the point where only normal costs of capital were covered. In the long run, supply curves for most of these sorts of services/products should almost flat.

My proposition is that there are few or no producer surpluses likely to arise from a trend increase in foreign tourism as a result of extending Wellington airport. But even if there were, any such gains would have to be offset against the loss of producer surplus for New Zealand producer (to foreign producers instead) from New Zealanders taking more holidays abroad. It makes little difference to the hoteliers if I take my holiday in London instead of Queenstown, while at the some time someone in Manchester takes his in Queenstown instead of taking it in London.

Even if the consultants are right that there would be more additional inward visitors than outward, any producer surpluses from either set of numbers should be small. And the net of two small offsetting numbers is even smaller.

The safest assumption, in evaluating the WIAL proposal, is to assume that the economic benefits of the proposal all accrue to users, and that there are no material net economic benefits (or costs) to the rest of the community. Perhaps there is a small amount in the net GST flow, but it is hardly worth focusing on given the scale of the other uncertainties.

Perhaps this point will seem counterintuitive to lay readers and city councillors. Surely “Wellington” or “New Zealand” is better off from having more foreign visitors (assuming the numbers outweigh the increased outflow of New Zealanders)? And if so, shouldn’t we – Councils, government – be willing to spend money to get those benefits? The short answer is no. Good and services cost real resources to provide, and in a competitive market simply providing more goods and services won’t make the city or country better off – you need to be able to sell stuff that generates more of a return than it costs to provide (including the cost of capital). Vanilla products and services typically don’t do that. After all, labour that is used to provide services to tourists is labour that can’t be used for something other activity. And over a horizon of 45 years we can’t just assume there are spare resources sitting round unused. Spending public money to generate this economic activity will come at a cost of some other economic activity being displaced (as well as the deadweight costs of taxation, which are allowed for in the cost-benefit analysis).

If, to a first approximation, there are no “net incremental economic benefits” for the “rest of the community” then even if the WIAL/Sapere passenger number estimates are totally robust, the net benefits of the project drop from $2090 million to $954 million.

In my earlier post, I noted that the cost-benefit analysis had been done using a 7 per cent real discount rate.

The authors defend it by reference to the Treasury’s guidance on evaluating infrastructure and single-use building projects (eg hospitals and prisons).

Frankly, I’m sceptical that that is an appropriate discount rate for this project. And I would be astonished if Infratil – the dominant shareholders in WIAL – treated their own marginal cost of capital for a project like this as being as low as 7 per cent real. Perhaps a case might be made for something that low in respect of projects that depend simply on existing traffic (growth) patterns – eg the current extension to the domestic terminal at Wellington – but at the margin this runway extension has the feel of a much higher risk project. After all, they could build it and no one might come. I’ve written previously about government discount rates, and also linked to a recent Reserve Bank of Australia article suggesting that private sector firms are typically using hurdle rates of at least 10-13 per cent nominal (almost as many in the 13-16 per cent range).

I would reiterate the point here. For a project like this, a much higher discount rate should be being used. Perhaps if it all goes wrong, WIAL itself might be able to recoup the costs from all airport users (I don’t know the Commerce Commission limitations on that), but even if so, this evaluation is being undertaken from a national benefit perspective. The risk of all users being lumbered with higher charges to cover the cost of a project gone wrong has to be factored in to any evaluation as to whether public money should be used. A 10 per cent real discount rate seems a pretty reasonable commercial benchmark, and the sensitivity analysis (table 33) indicates that using a 10 per cent discount rate rather than a 7 per cent rate roughly halves the estimated net economic benefits of the project on the “most likely” scenario.

Using a higher discount rate and removing the producer surpluses (that are most unlikely to exist) would reduce the estimated net national gains of the runway extension proposal – advertised at in excess of $2 billion – by around three-quarters, even if the passenger number estimates were totally robust.

If one uses the low scenario instead (Table 33), net economic benefits are estimated at $802 million. But $533 million of those benefits were estimated to accrue to the rest of the community – and I’ve argued that those producer surpluses just don’t exist to any material extent. And on that scenario, using a 10 per cent discount rate reduces the net economic benefits by 57 per cent relative to the estimate done using a 7 per cent discount rate.

Perhaps there is a viable proposition in all this for the airport company itself. I rather doubt it. I suspect that the additional landing and passenger charges that would have to be levied on the new wide-bodied/log haul services would undermine the additional demand to the extent where it was simply uneconomic to provide those services. Wellington doesn’t look like a natural place for economic long haul services. But that should be the airport company’s call, with their own money at stake

Councils – and especially Wellington City Council – should steer well clear of the temptation to put ratepayer money into this proposal. It is not as if Infratil appears to be proposing to reduce its stake in the airport. What is apparently proposed is a ratepayer/taxpayer capital subsidy, without the councils gaining any additional ownership interest. If things go wrong, the airport company itself may well, over time, be able to recover its investment, since many people need to use Wellington airport. Even if things go right, the Wellington City Council has little way of recouping the cost of its gift/investment. And if things go wrong, it has no way at all. Only the chimera of alleged “wider economic benefits” could lure otherwise intelligent people into a proposition with such a weirdly asymmetric payoff structure.