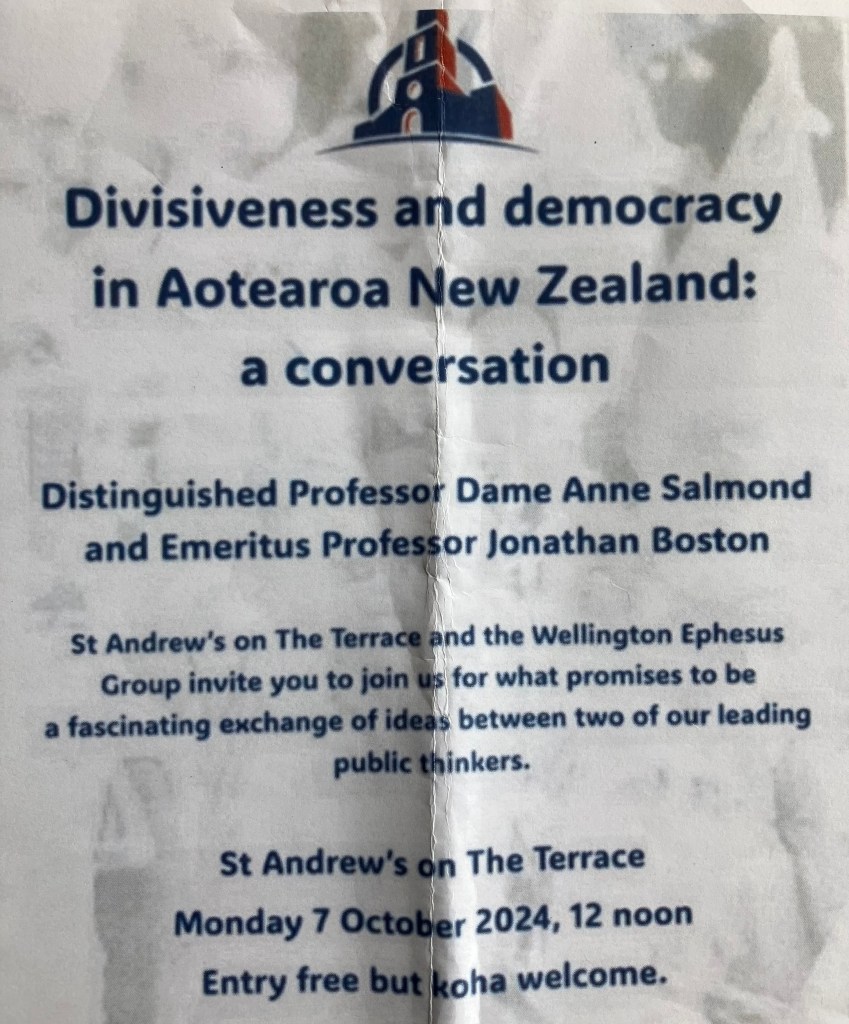

Not the usual stuff of this blog, but at lunchtime yesterday I went along to this well-attended event (St Andrew’s was full).

I had a few reactions and didn’t think I could do them justice in a few quick tweets.

Why did I go along? Well, several reasons really. Being semi-retired one has time, in principle the topic sounded interesting and important, I’d never heard Salmond speak before, and I have some time for Boston. I can’t say I necessarily expected to agree with the thrust of the promised “conversation”, but it is always good to hear people you disagree with make their best cases. Boston noted that it was a rare event at which he lowered the average age (and he is a few years older than me).

As it happened, Salmond did most of the talking, while Boston acted more as guide and host to the conversation (although he threw in some more comments in the Q&A session, including stating his preference to raise the NZS eligibility age to 70 – I clapped at that point). He sought to structure the discussion under 4 headings: treaty issues, environmental issues, the future of democracy, and “what on earth should we do now”.

Of course, I should have anticipated that the “conversation” wasn’t really going to be anything at all disinterested. If you were concerned about the way in which politics and society were going, and were interested in exploring common ground, rebuilding trust, engaging in efforts towards mutual understanding etc, you certainly wouldn’t have taken Salmond’s approach. From Salmond’s side in particular, it was mostly a series of sneers and laments about this government (David Seymour in particular, and Christopher Luxon who seemed to have fallen into the hands of bad people).

(As regular readers will know I am not myself a particular fan of this government, have little time for either Seymour or Luxon, and do not support Seymour’s Treaty Principles Bill.)

If inflammatory language is one of the problems of our day, Salmond contributed more than her fair share in just one session. Had anyone who strongly disagreed with her own politics been present they’d not have felt as if Salmond had any interest in them, except to sort them out and put them on the straight and narrow, or any recognition that there might be legitimately competing interests, world views, models for how policy should be done or New Zealand governed. Instead – particularly on treaty issues – we got sneers at how David Seymour couldn’t read Maori (which seemed particularly strange from someone of wholly European ancestry re someone of part Maori ancestry), claims that his approach was “impertinent”, that it was all “heartbreaking”, and that “it takes a lot of work to remain as ignorant as many of us have been”. It was, apparently, okay to have a discussion about the Treaty of Waitangi, “but not like this” – more, it seemed, a case of it was okay for the unwashed to ask questions of the experts and be put back on the right path, as if historical research (fascinating as it often is) was the answer, rather than one contribution to dialogue and debate as to how a modern New Zealand should best be governed, and what (if any) ongoing role an 1840 treaty might play in that.

The government was then accused – in the calm moderate language that fosters dialogue – of an “ambush of our democracy”, a claim which appeared to apply not just to treaty things but to the environment. This government, we were told, “is going in the opposite direction to our survival as a species”. Strangely – or perhaps not – the fact that the ETS continues in place, which caps emissions across the economy as a whole, was never mentioned. The fast track list seemed very unpopular……and yet of course there was no mention of projects fast-tracked under the previous government. Perhaps one line I might welcome was that there wasn’t much evidence of the coalition agreement commitment to evidence-based policymaking, if only it weren’t that successive governments – of both political stripes – have been so poor on that score.

And if the rhetoric hadn’t been amped up enough, we were then told that the government was “tossing whole categories of people on the rubbish heap”, while being invited to evaluate the government on how many New Zealanders were leaving, the suggestion being that it was because of this “ambush of democracy” – as if this hadn’t been a stark and sad feature of New Zealand, across governments except when the borders were closed, for too many decades.

I’m sure it was quite entertaining and emotionally satisfying for the much of the audience – and there were audible gasps of approval when she quoted Nobel economics winner Paul Romer to the effect that “we must stop apologising for regulation. It is the only thing that protects us from the abyss” – as if no one had noticed that David Seymour’s own new ministry is actually called the Ministry FOR Regulation.

I suspect that Boston was pretty sympathetic to a fair amount of Salmond’s commentary but he did inject a moment of realism, noting that the government (and its component parties) are about as popular now as they were in the election last year. If good Christopher Luxon (Salmond had been keen on him at Air NZ) really had fallen among the disreputable, “many of our fellow New Zealanders” seemed to quite like what he was doing.

(Now again to be fair, Boston seemed distinctly unimpressed with the Labour Party, and Salmond with the Green Party, so perhaps they might think it was all just the failures of the Opposition).

Salmond seemed dead keen on allowing New Zealand policy to be shaped by international “great and good” people: we got repeated references to various reports of Nobel Prize summits. It wasn’t quite clear how this was going to help her treaty concerns, but I guess she had in mind the environment. Quite why we’d want New Zealand policy to be guided by a bunch of people who are very expert in usually quite narrow technical areas, when most political hard choices are about values and distributional tradeoff, wasn’t ever made clear. Salmond seemed very keen on “citizens’ assemblies” and exercises in so-called “deliberative democracies” but presumably only so long as people like her got to guide the material these selected citizens were presented with. More money for journalism, and public broadcasting in particular, seemed to be a policy line both Boston and Salmond were championing, seemingly utterly oblivious to the declining public trust in journalism.

Perhaps weirdest of all was the way Salmond ended. Apparently oblivious to Boston’s reminder that the current government isn’t exactly unpopular (at least outside central Wellington) there was an impassioned plea that we should “let leaders lead”. Since I doubt she in mind Seymour, Shane Jones, or even the diminished Luxon, one can only assume it was only the right sort of approved leaders who should be allowed to lead. In a final flourish of no nuance whatever, we were told that we needed leaders who would look to the interests of their children and grandchildren, not to the interests of donors. A particular unconstructive approach to enhancing mutual respect etc to simply assert that everyone who disagrees with you is either ignorant or in the thrall of donors, and has no concern for next generations (even their own) at all. It really was quite breathtaking.

Perhaps if one went along to an ACT rally, or even a New Zealand Initiative members’ retreat, it might all be about as bad on the other side: the dismissive sneering and the automatic assumption of a single right pathway, if only the peasants could be cowed or brought to understand. Maybe (I genuinely don’t know). For myself, I’m sceptical of constant calls for “social cohesion” etc, since there are really big and important differences and values and world views and priorities, and there isn’t much point in assuming that one side or the other only needs to be enlightening (or perhaps silenced). But it really was astonishing that someone as able in her own field as Salmond evidently is, had no apparent interest in anyone else’s models or values or frameworks, or even a conception that there could be such things: the people of goodwill and intelligence might genuinely, deeply, and perhaps intractably disagree.

But it probably all played well to the elderly base present at the meeting. Just like so many gatherings – so much social media for that matter – do.