On Friday morning I picked up my copy of The Post to find on the front page a story clearly handed to Stuff’s political editor Luke Malpass, about a shiny new intervention that ministers were to announce later that morning to help out residential property developers. It was, we were told, going to offer free downside price/liquidity insurance to large and established property developers. It would be sold as strictly “time-limited” except that there would, in fact, be no time limit specified.

My reaction on Twittter was “What…….” and it brought to mind that old jeer about business-friendly (as opposed to pro-market) governments and an enthusiasm among some of their supporters to “capitalise the gains and socialise the losses”. Little did we imagine that this would in fact become declared and intended policy of this National/ACT/NZ First government (not in the midst of a crisis, where sometimes these things happen, but as a whole new policy tool). I’m not generally an ACT fan, but……you have to wonder what the point of an allegedly pro-market anti-intervention libertarian party is if they wave things like this scheme through Cabinet (and not even their backbenchers have issued statements of disapproval, they being rather freer than ministers).

Malpass’s report was quickly proved accurate, with the announcement later that morning by Chris Bishop and Chris Penk (ministers of housing and of building and construction respectively) of the Residential Development Underwrite scheme.

The fact that it appeared to replace but considerably extend schemes in place under Labour was not a point in its favour

Funding for the RDU will be redirected from unused funding from the Kiwibuild and BuildReady Development Pathway programmes. Both of these programmes are now closed to new applications.

This government (rightly) having made much of inheriting a large structural fiscal deficit, and wanting to get government out of business, instead jump in boots and all. And all apparently on the basis that a couple of Cabinet ministers and their MHUD officials know better than the market what should be built when, where, and by whom, and thus who will win the benevolence of the free government underwrite.

There was more information on the MHUD website, but it was no more reassuring. There was no sign of any analytical framework behind any of it (no analysis at all, let alone anything serious or rigorous. of market failures or any sort of cost-benefit analysis or risk assessment). In fact, there was a distinct sense of something that had been rushed out. Some property developers had presumably been bending the ears of ministers. As the Herald put it “the government is riding to the rescue of stressed property developers”, in a distinctly picking-winners approach to the recession. Plenty of people and firms will have undergone huge stress in the last couple of years, as inflation was squeezed back out of the system. It was and is a necessary adjustment. But most apparently didn’t enjoy the favour of ministers.

And will no doubt do so again. In one article on Friday, Bishop was quoted thus

Bishop said the scheme wouldn’t be in place forever and Cabinet would make decisions about when to “turn it on and off” depending on demand and construction activity.

So that would no predictable and rigorous framework, but rather a great deal of trust in ministers’ ability to forecast construction cycles and housing demand, or to respond to pressures of the electoral cycle or developers bending their ears. Good regulation – like a good tax system – is stable and predictable, not turned on or off at the whim of ministers. This is poor policy, done poorly. And isn’t it simply dishonest for a government department to repeat ministerial spin about the intervention being “time-limited” (and MHUD does exactly that upfront) when there is no time limit at all? After all, in the grand scheme of things every policy intervention will eventually be altered/amended.

In essence what the scheme involves:

- the government will guarantee to purchase at an agreed (in advance) price houses that don’t sell at an (approved) market price within an approved period of time,

- only large-scale developers will be eligible for this assistance, preferably those building in Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch, Hamilton, and Tauranga [a little surprised Queenstown wasn’t on the favoured list),

- no fee will be charged for this put option that is being granted to the developers

The rationale appears to be that banks and other potential lenders aren’t sufficiently willing to take risks on this projects, even at high fees/interest margins, but……government knows better/best. Quite why we are supposed to believe this self-delusion (ministers and officials falling for it is perhaps more understandable – if no more excusable – given the nature of their incentives) is never made clear. Minister are, it appears, blessed with some special insight into the state of the economy and the timing/speed of the recovery, and instead of just (say) publishing that analysis, they prefer to give handouts (and that is what free price/liquidity insurance is) to developers.

In the MHUD document there is this statement upfront

The secondary objective never seems to get another mention, but the ‘primary objective” is almost worse, for being functionally meaningless. You minimise the cost and risk to the Crown by simply not offering free insurance, and if you must offer such insurance you should do so with a disciplined and transparent model (to, for example, estimate the economic price of the option). But there is nothing of that sort in any of the MHUD material, just a lot of mention of the (extensive) discretion afforded to officials, of whom we may be left wondering both what their expertise is and what their incentives are. Why would we back them to make better choices than financial market participants? And as for “maximising housing supply”, there seems to be no analytical framework there either, including around incentives on developers (who will, of course, prefer free insurance and can be expected to try to game the rules). Will there be any material impact on supply, will any impact be any more than timing, and how will MHUD rigorously evaluate claims put to them by developers? Oh, and isn’t developers finding themselves with overhangs of houses and land part of the way that much lower house prices actually come about?

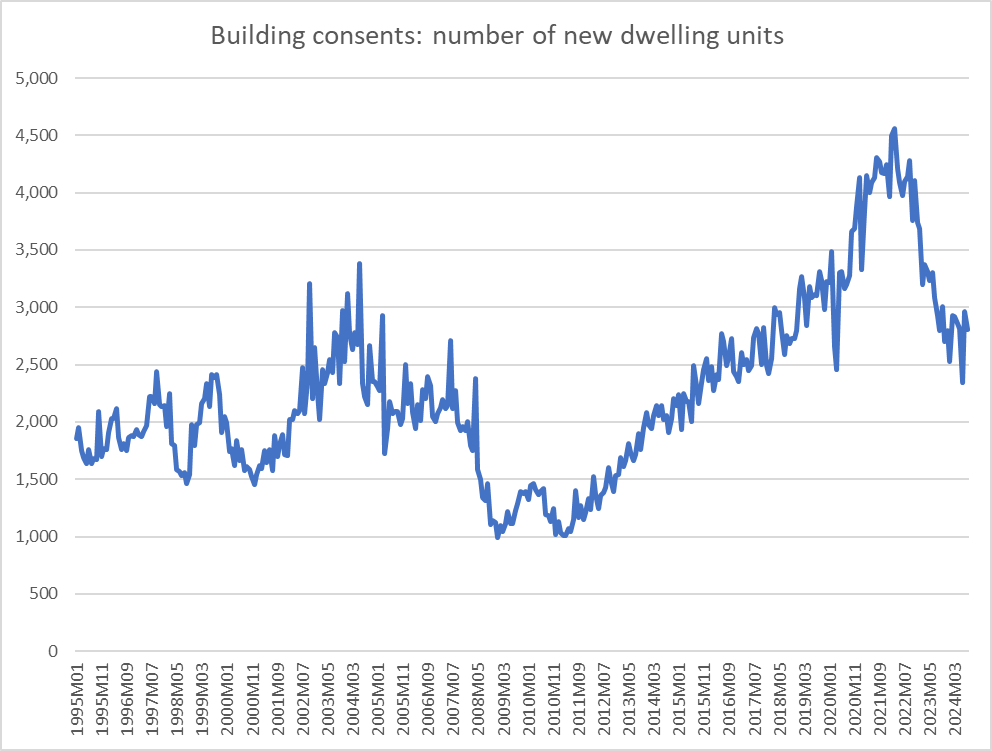

It is possible the scheme won’t end up being hugely costly. After all, house prices might take off again as interest rates fall. Or officials might err on the very cautious side and very few underwrite grants might be made (or at such deep discounts that the real insurance cost is cheap). But there is just no good or compelling analytical foundation for any sort of intervention of this sort (none provided, none readily conceivable). Even the business cycle argument seems rather flakey. Ministers seem to lament the cyclicality of residential construction (globally, it tends to be one of the most cyclically variable components of GDP), but when they lament the state of the industry, they don’t mention that new residential dwelling consents are still running around twice the level at the trough of the 2008/09 recesssion.

There is also talk about helping to get the cyclical economic recovery underway. Pretty much all the arguments against using fiscal policy for that purpose – I’ve outlined them here repeatedly – apply at least as much to discretionary sector-specific interventions like the Residential Development Underwrite. And, of course, were the Reserve Bank to regard this scheme as being likely to make a material difference it should, all else equal, make them more reluctant to, with less scope to, cut the OCR a lot further.

It is a rather sad reflection of how the quality of New Zealand policymaking has fallen. Perhaps we should be grateful that exchange rate cycles aren’t what they were – and that past governments were less prone to scheme like this – or who knows what sort of free insurance the government would be dreaming up for exporters.

Who knows what the relevant government agencies thought of this scheme. I’ve lodged OIA requests and am particularly interested in any analysis and advice from The Treasury and the Ministry for Regulation.

I’ve been reading your articles for many years. Some I don’t understand. This is the first to leave me gob-smacked. This will gives governments a real incentive to aim for high inflation. Will our taxes be rewarding foreign developers? It is a policy that can only work if politicians and their public servants are all-knowingly wise and absolutely incorruptible. Ask the CCP to administer it for us; they have experience in rapid building of apartments.

LikeLike

And look at the timing – this announcement on Friday – and then the list of 149 fast-track projects released on the weekend;

https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/political/529962/government-unveils-149-projects-selected-by-fast-track-approvals-bill

Link to embedded .pdf in that article.

Pork barrel to accompany their picks.

LikeLike

Hi Michael,

In my humble opinion, this sort of thing all started around 4 years ago, under the illustrious (be kind) leadership of the fabled Ardern. She clearly operated like a puppet on a string, but what was more annoying was the little pushback she and her cronies received from the opposition. The response to an announcement of another crazy idea seemed to be: Oh well, it is their turn now, and soon it will be ours. Those of us watching the circus were outraged.

What is more infuriating is the salaries their so-called advisors are on, earning around $ 500 k a year with glorious handshake clauses, regardless of outcome. A while ago I saw an email in circulation quoting the salaries of these highly-paid civil servants, and the document was 2 years old at the time, with some eye-watering numbers on them.

That reminded me of a blog I read many years ago where this young girl (very naïve) decided to work for one or other UN agency somewhere in Africa, going out there with a ‘I’m going to save the world attitude’. Around 18 months later (and a massive reality check) she wrote about her experiences, and the most notable thing was this: In these African countries people try to get a govt job, and from there on use every lever they’ve got to enrich themselves with total disregard for the struggling people they are meant to help.

I’m realizing more and more that this sort of behaviour happens everywhere, not only in Africa or Asia.

Regards, Jan

LikeLike

I think the problems date back further than that, probably to at least the Clark govt. The decline of the Tsy dates to that period, and so did the strong and instinctive reluctance to do special deals. handouts etc . The Key govt was no better – look at the special deal around the Auckland convention centre for example. And film subsidies galore……embraced by both main parties.

LikeLike

Coming to think of it Michael, you are 100% correct. I used to operate (mostly) ignoring politics, but not anymore.

So after 3 successive govts, the bar is now so low that it would appear ‘that nobody cares’. Oopss…another $ 50 mil down the drain. Just ignore it and carry on while we borrow or print some more.

If any of us in our private or business capacity operated like this we’d be dead bankrupt, and barred from ever operating a bank account again.

LikeLike

Bankruptcy is a 3 year period. Not forever. Also in many business cases where a business is in financial strife, assets are restructured out to a separate entity before a company is put into liquidation and in most cases bankruptcy is avoided and assets are preserved to fight another day.

LikeLike

Just an acknowledgement that this version of my comment is from Chat GPT – I can send the original if required but this is much better written and more succinct.

As someone who embraces MMT, this policy stands out as a clear example of fiscal intervention during recessions. The government’s underwriting of housing projects signals that, despite pro-market rhetoric, they acknowledge the need for fiscal levers alongside monetary policy. Keynesian principles—supporting the private sector to mitigate recessionary effects—are in play here, even if it’s framed differently. I predicted this move after the May Budget as a necessary step to restart the economy, though I expected it closer to the election.

What’s striking is the tone of criticism in the article, which implies that the government’s involvement in supporting developers is inherently flawed. The article suggests that the “pro-market” solution would be to let developers and banks respond naturally to lower demand, downsizing or shifting to high-margin luxury housing while waiting for the construction cycle to lower costs. In this view, the economy would eventually reset, with cheaper labor and materials as inflation and interest rates fall.

But the critical question is: why is the government doing this now, especially when it risks political capital with free-market advocates? The answer is simple—productive capacity. The construction sector is being hit hard, losing jobs and business capacity due to the government’s earlier pullback on public sector projects. The Reserve Bank didn’t fully anticipate the scale of this contraction, which has broader implications for the economy. If we lose too much productive capacity now, it becomes harder to make future growth investments when the labor force and expertise are diminished.

In other words, while the policy may look like a bailout for developers, it’s about preserving long-term economic capability. The government understands that you can’t just “crash” the economy to fight inflation without losing the means to recover later.

Finally, the policy highlights class politics in action. The shift away from public housing (like Kainga Ora’s 6,000 homes per year) towards taxpayer-funded middle-class developments suggests a preference for appeasing wealthier constituencies. The government may dress this up as “unlocking capital” for investors, but ultimately, it’s about maintaining a flow of income into the private sector, as MMT predicts.

LikeLike

Won’t respond to the substance, but it is certainly quite impressive what Chat GPT can do.

LikeLike

Yes – it’s amazing and this is quite different from what I wrote but incorporates the same key points. It knows the type of language that is required for the topic so it phrases things in terms that will be familiar to economists much better than me.

LikeLiked by 1 person