2024 will mark 40 years since the great acceleration of policy reform that began with the election on the 4th Labour government in July that year and ran for the following decade or so. I’m sure there will be lots (and lots) of reflections on the period later this year, most especially from the left where the ongoing political angst seems greatest (yes, it really was a Labour Cabinet that kicked off the process and did many of the lasting reforms, much as some on the left remain very uncomfortable about that).

If one thought about the big economic issues that were around at the time, they could probably be grouped under three broad headings:

- inflation

- fiscal deficits and government debt, and

- productivity

One might add to the list the balance of payments current account, which became no longer a policy problem once capital controls were lifted at the end of 1984 and the exchange rate was floated in early 1985. (Yes, recent deficits have been very large, but as a symptom of other imbalances, rather than a policy issue in its own right.)

Of that list, New Zealand has done fairly well on the first two items.

We used to have among the worst inflation record among the advanced countries (high and variable), but in recent decades we - like most advanced countries - have done much better. The last three years have been a bad lapse, but if that never should have been allowed to happen, the ultimate test is whether things are got back under control, and we seem now to be on course for that (eventually the lagged infrequent data will emerge). I’m not here going to get into lengthy debates about other countries, but whatever the common shocks once a country floats its exchange rate its (core) inflation outcomes over time are its own choices (see Turkey for any doubters).

We’ve also done pretty well on fiscal policy imbalances. There are plenty of leftists around who think taxes and spending should have been, and should now be, higher, but my focus is imbalances (deficits and debt). Again, the last few years (post Covid spends) have been bad, but under governments led by each main political party, New Zealand has over decades done a reasonably good job of keeping debt low and reining back in deficits when they have first blown out. And our system of fiscal policy transparency is pretty good too (although like almost anything could be improved).

One could throw financial stability into the mix. Almost every country that liberalised in the 80s ran into serious financial sector problems a few years later (neither the private sector lenders and borrowers nor the putative regulators really knew what they were doing, perhaps unsurprisingly after decades of financial repression), but the last 30 years have been pretty good. Lots of finance companies failed 15 years ago, which wasn’t necessarily a bad thing (risk and failure are integral parts of a market economy), but the core of the financial system has been sound and stable. Plenty of countries would have traded that record for their own experience.

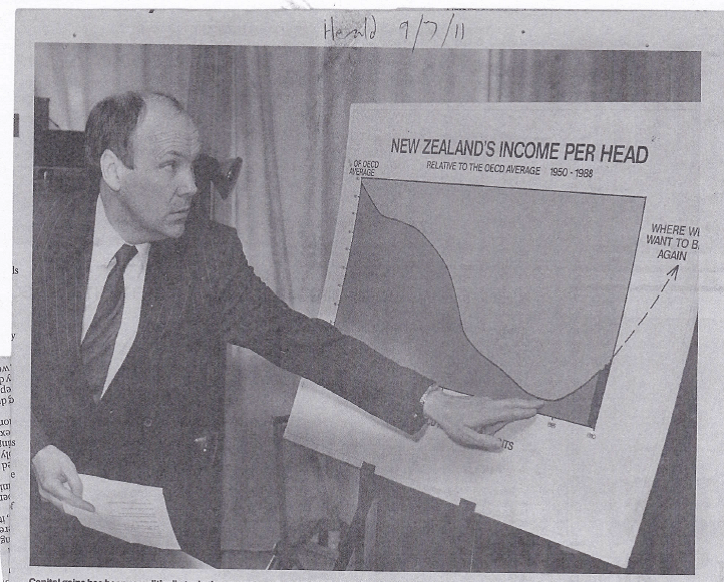

The big hole in the story has been around economywide productivity. 40 years ago people were highlighting how far New Zealand’s performance had fallen (official reports from as early as 60 years ago were already drawing attention to growth rates having slipped behind), and the hope/aspiration was to turn that around. This is one of my favourite photos (reproduced in the Herald a decade or more ago, but showing late 80s Minister of Finance David Caygill)

Even though there had been not-insignificant economic reform and liberalisation over the previous few decades, in the early-mid 80s it was easy to highlight the many very obvious inefficiencies in the New Zealand economy (car assembly factories dotted around the country to name but one example). The previous decade in particular had been a very tough time for New Zealand - hardly any productivity growth at all after 1973/74 – probably less because economic policy became particularly bad (one could quite a long list of useful and important reforms, alongside other problems and new distortions - eg Think Big) than because the terms of trade were very weak.

Almost as bad as the worst of the Great Depression, but averaging low for longer. Exogenous adverse shocks to both export and import prices impeded the ability of the economy to generate high average rates of real productivity.

As recently as 1970 (when the OECD real GDP per hour worked data start) and despite decades of inward-looking policies New Zealand’s average productivity still didn’t look too bad. We were below the median OECD country but not by much, just under the G7 median, and more or less than same as the big European countries (UK, Italy, France, Germany). By the time of the 1984 election we’d slipped a long way further.

We were by then around the same as Greece, Ireland, and Israel, and of the G7 well behind all except (still fast-emerging) Japan.

Here is where we are relative to the same group of OECD countries in 2022

We’ve clearly pulled away from Greece, but that is about the only semi-positive I could find (and yes, the gap to Italy has closed somewhat as well). For what it is worth, on the data to hand so far 2023 looks to have been a year when New Zealand average productivity fell.

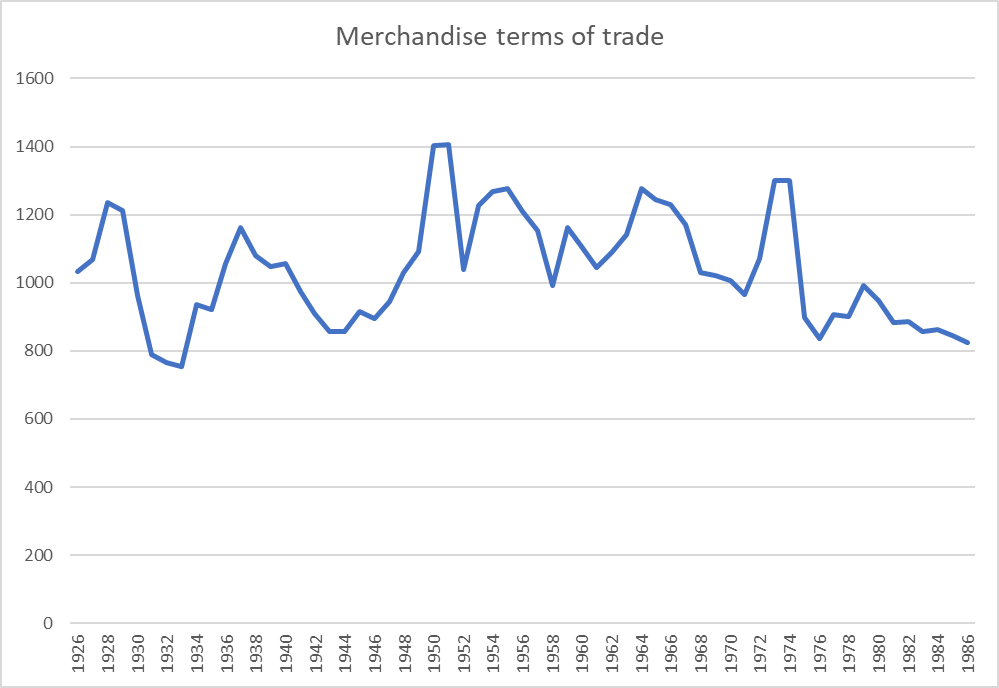

Of course, the rate at which we’ve been falling down the league tables has slowed. But then remind yourself what happened to the (merchandise) terms of trade

They have trended upwards since the late 80s (I remember our puzzlement at the RB when the first late 80s lift happened) and especially in the last 20 years. On this measure (which excludes services, to get a long-term consistent series) the terms of trade have averaged higher than at any time in the last century. And yet still average productivity languishes.

There are of course a whole bunch of new OECD members since 1984. A large group of them were then either part of the Soviet Union or communist-bloc countries, even the least bad of which had much more messed up economies than New Zealand’s. This is how we compare now with that group

Middle of that pack to be sure, but probably not for long on the trends of the last couple of decades. South Korea is just about to go past us too.

It really has been a shockingly bad performance by New Zealand, against what would normally have seemed a propitious background - a sharp sustained recovery in the term of trade and a much greater reliance on letting market price signals work. There isn’t much serious basis for wishing away this failure.

And yet there seems to be little sign that our politicians or their official economic advisers have much interest, or any serious ideas for finally reversing the decades of real economic relative decline.

It is as if the powers that be and those around them have simply become resigned to our diminished fortunes, indifferent to what that failure means for actual material living standards now, and those for our children and grandchildren to come.

Yes we have done very poorly. Personally I think that we needed to have and still need to have some target for research and development eg 3 per cent ie there needs to be more investment by both public and private sector players so that we have new industries creating high value goods and services. Unless we as a country get richer we cannot afford the levels of health care and other services we expect. We also need to get richer so we can put more money into large climate change issues.

Frank Lawton.

LikeLike

One R&D project comes immediately to mind. Rocketlab. This initiative was assisted with a government R&D grant of $90k and subsequently sold to US interests for $350 million and is now a US company valued above $4 billion. So where did the NZ taxpayer gain? Certainly not in the eventual sale of $350 million and certainly zero interests in the subsequent $4 billion valuation. But yes NZ does have a Space Industry with a 10 billion trade which does employ people and make rockets that we do launch from NZ. You could argue a big pay off for the NZ economy for that $90k R&D spend.

LikeLike

Correction: NZ Space industry is around $2 billion and not $10 billion.

LikeLike

That’s the problem when your only economic strategy is low value immigration – i.e., sadly the ACT Party’s current policy – https://www.act.org.nz/immigration – looks only to repeat the past ‘population’ exercise.

Unless someone sees that any of these policies – https://www.act.org.nz/economy – will serve to address our productivity problem?

LikeLike

The frustrating thing about ACT is that they are the only party to care enough about productivity enough to put out a serious document https://assets.nationbuilder.com/actnz/mailings/6523/attachments/original/230905_ACT_%28Tackling_Our_Productivity_Crisis%29_Policy_Document_A4.pdf?1693863432

but also totally wedded to v high immigration as a policy strategy (that had already failed for 30yrs now)

LikeLike

Agree – at least they are thinking about it – the reason I mentioned them. In addition to that failed population policy strategy of successive governments, their website policies under the Economy heading, seem to me to be focused on efficiency measures as the second pillar. But improving productivity is more than that, I think. And you never get their by importing low wage labour – that actually works against a lift, as no one needs to innovate when labour is so cheap.

LikeLike

The productivity equation has always been a difficult calculation in New Zealand. Previously with 70 million sheep to export and a captive UK market our low population had high productivity simply because productivity only considered monkeys or humans as the denominator and not the 70 million sheep. For many years our dairy and beef industry provided the productivity with its incremental year in year out increases until we reached a peak 10 million cows. Again counting monkeys and conveniently our economists forgot to count the 10 million cows and 40 million sheep.

LikeLike

Frightening stuff.

There will be no turn around until decades and decades of bad regulation are addressed and removed!

Productivity declined as bureaucracy grew.

Government constructs such as the ETS , Forestry etc are living off subsidies along with tourism and any number of other Government anointed activities crowding out any productive growth .

Government has choked entrepreneurial activity in NZ by over government.

What will the new Government bring?

LikeLike

On your final question, not very much (judging by either campaign indifference or the coalition agreements.

LikeLike

And yet we were consistently in the top three countries in the world on the ease of doing business index. For the last four years on record, we were first. There are narratives in New Zealand that need to be challenged, if only because of the effect they have on business confidence. E.g. this, and CGT.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ease_of_doing_business_index#

LikeLike

Technically easy to set up and run a business here (at least by international standards), which suggests the issue is about opportunities; profitable ones probably aren’t just being left on the table by private sector firms and entrepreneurs.

LikeLike

Excellent comment Michael and it is plain bloody annoying that our policy makers are busy doing everything but take an initiative on the problem.

LikeLike

How does the recent increase in the public sector employment influence productivity?

Can the latter be even reliably measured?

LikeLike

In the core public sector (where there is no market price for products) inputs (mostly labour) are mostly used for GDP measures. All else equal a big increase in core govt employment is likely to have dampened “true” labour productivity a bit (whether that is reflected in the actual data is another question). Many analysts focus on “market sector” data – I tend not to since it is available only annually, with longish lags, and is harder to compare against other countries’ experiences.

LikeLike

I recall hearing, perhaps around two decades ago, that much of New Zealand’s faith in the stock market collapsed after Black Monday in ’87. Following that, Real Estate became the investment of choice for many. Given that prices are up to three times what is regarded as ideal now, there must be a gigantic amount of capital tied up in it that could have been invested more productively?

Otherwise, what are we doing differently to the countries that have passed us?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Douglas,s Labour (Plus Ruth Richardson and her mother of all Budgets) all promised removal of all subsidies.

But both were constrained by political considerations and removed subsidies from the small high producing sectors and transferred those subsidies to social spending.from the tradeable sector.

The government is still subsidising and picking winners.—Weta workshop, labour market etc etc.The Carbon market and forestry is one of the worst

Let us not forget the inherent tax and subsidies in an overvalued exchange rate .And yes,.inflation taking from those with fixed incomes to “add value” to the housing stock.

( By the way there are only approximately 20 million sheep left in NZ down from 73 million in the 1970s .We are also nett importers of pork.Manufacturing has also declined hugely.)

The NZ economic pie is much smaller leaving less to share with immigrants

Unbridled immigration can not help NZ

LikeLike

Interesting commentary from Monash University re Australia’s skilled migration programme https://theconversation.com/australias-skilled-migration-policy-changed-how-and-where-migrants-settle-215068

The takeaway: “evaluating whether the skilled migration policy has been a success involves understanding whether or not highly educated immigrants are finding jobs that match their qualifications. Our research suggests this hasn’t been the case.”

Would New Zealand be any different?

All indications are the more people we gain, the poorer per capita we become.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Michael,

I’m wondering which countries have seen the highest quality growth in Real GDP phw over the same period? And if there are learnings from such examples as to policy best practices to drive this?

LikeLike

Hard to know how one would think of defining ‘highest quality’ in this context. The strongest growth has been from South Korea, Turkey, and the former Communist central European countries. But catch-up growth can be easier than being a frontier country – those with the highest levels of productivity – and as far as I can see none of those frontier countries (US and much of NW Europe) have stood out in the last 20 yrs or so.

LikeLike