The Herald ran an op-ed yesterday under the heading “Why the Government’s new Reserve Bank mandate may lead to worse outcomes”. It was written by Toby Moore who served as an economic adviser in Grant Robertson’s office while he was Minister of Finance (a fact the Herald chose not to disclose to its readers).

I’m more interested in the substance of his argument. Moore is a serious guy, and I suspect he’d run his arguments whether or not he’d ever taken up a role with Robertson. But I think his core argument ends up not very persuasive.

Moore opens his article pointing out that there isn’t an overly strong economic case for having reverted to something very like the old statutory objective for monetary policy. There are certainly bigger economic challenges (albeit probably not ones the law draftsmen could tackle as quickly). As the Governor repeated again yesterday – while trying to minimise the extent to which the previous wording was actually a “dual mandate” (a point on which he was correct, but not a point he’d have made often under the previous government) – no monetary policy decision in the last few years was made differently because of the revised wording of the statutory mandate. That is entirely convincing: the Reserve Bank’s big mistakes (and they were very big mistakes) were forecasting ones. Given their forecasts their OCR choices made (more or less) sense. But they misunderstood how the economy was operating and how real the inflation risks were.

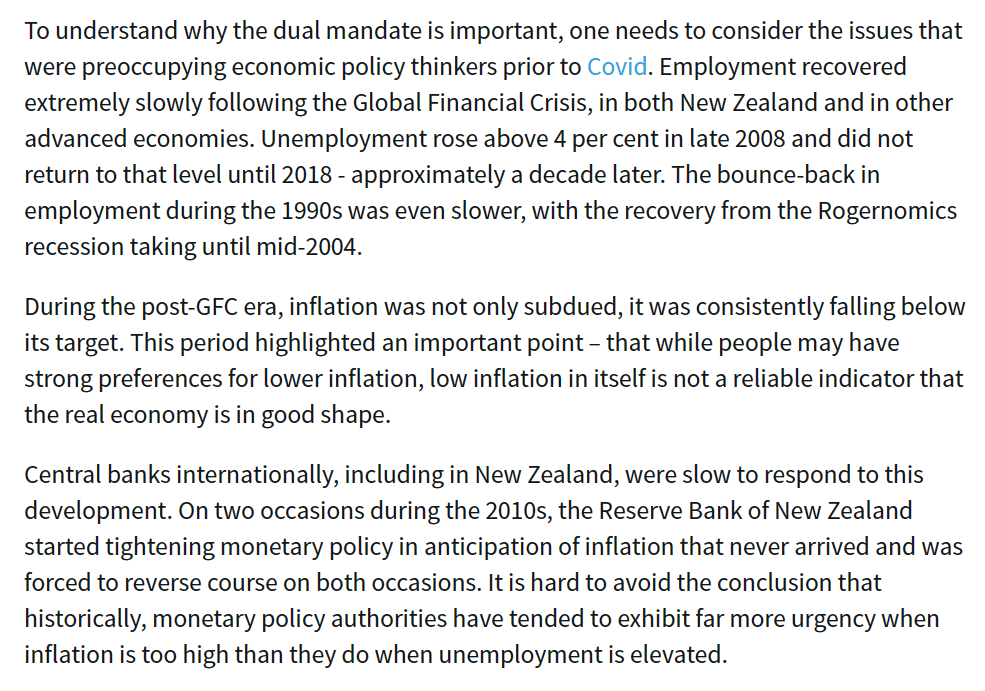

But then Moore attempts to argue that much of the previous 30 years would have been different (and better) if only the Reserve Bank had spent those decades operating under the statutory mandate it had from 2019 to 2023. The episode I want to focus on is that from a decade or so ago. These are his words

One can see the issue more starkly in this chart

As one added bit of context, in 2012 a requirement was added to the Policy Targets Agreements requiring the Governor to focus on delivering inflation near 2 per cent, the midpoint of the 1-3 per cent target range.

I agree with Moore that a series of bad monetary policy choices were made by the Reserve Bank during this period. In fact, while I was still at the Reserve Bank I argued against the proposed tightening cycle that eventuated in 2014 on the twin grounds that core inflation was very low, and (consistent with this) evidence from the labour market suggested quite a lot of slack still in the economy. Once I left the Bank in early 2015, it became a regular theme in commentary on this blog.

But…..the key point is that, once again, economic forecasts were very wrong. The Bank’s forecasts during this period usually had core inflation coming back to the midpoint and needing higher interest rates to keep it there.

And actually I think there is a fair argument - that should appeal to Moore, although not to some others - that during in 2010s one problem was that the Governor, having recently returned from a long sojourn in the US, became fixated on the housing market and the US crisis of 2007-09, and constantly wanted to orient policy to lean against such risks, without ever stopping to consider (a) similarities and differences between NZ and the US, or (b) his statutory mandate. It wasn’t the biggest factor in setting monetary policy wrongly – policy that delivered core inflation bouncing near the floor of the target range for years – the problem was forecasting failure and bad models – but it didn’t help either.

A central bank in the early 2010s (a) strongly focused on the inflation target, and (b) with better forecasts/models (or just looking out the window) would have delivered a lower OCR during that period, and in particular would not have championed a substantial tightening in 2014. That would have had better outcomes for inflation and for unemployment.

Reasonable people can differ on how best to specify and to articulate what we look to the Reserve Bank to deliver with monetary policy, but the problem a decade ago wasn’t some excessive focus on inflation, but a poor understanding (shared of course with many others here and abroad) of just what was going on. Arguably, looking out the window - at actual headline and core inflation - might have given a better steer during that period. A ‘dual mandate’ simply wouldn’t credibly have made any difference, given all else we know. The unemployed paid a price for those limitations/mistakes (as holders of fixed nominal financial assets have paid a big price for central bank mistakes in the last year or two).

Excellent central banks matter. They make a difference to real people, real outcomes. It would be good if we had one, and/or a government seriously resolved to deliver a better one.

Good article.

My tuppence worth (or given inflation since those days, perhaps my dollar’s worth) is that whether the dual mandate would have changed past decisions in the absence of stagflation is a bit of a navel-gazing sideshow.

The problem instead with multiple objectives for a single policy instrument is that purposeful decision-making is formally impossible when they are in conflict. That makes decent accountability impossible.

So when there is a dual mandate and both inflation and the unemployment rate are high, what is a central bank meant to do? Toss a coin?

The other point is that monetary policy determines the price level in the medium-long term, but not the unemployment rate. So, if one or the other is to be the prime target for monetary policy, it makes sense for it to be the former.

LikeLike

Thanks Bryce. Adrian, backpedalling fast at FEC yesterday, did note that technically the old formulation was not a “dual mandate” (employment was subordinate to inflation). Personally I’d be happy with a formulation that more explicitly articulated that: eg keep unemployment as low as possible, consistent with core inflation remaining inside a 1-3% range with a midpoint of 2%)

I’m less persuaded on the accountability point. On the one hand, it is quite clear central bankers failed in 2020 to 2022, and then a great deal of judgement is inevitably involved in the question of whether they should pay a personal price (eg how inexcusable, how idiosyncratic, was their forecast error?). I’ve come round to a more hardline view: the price of well-paid autonomy has to be serious accountability so if you mess up this badly you should lose your job, even if there were (and there almost always will be) some mitigating arguments. Not as if anyone forced them to take MPC positions.

LikeLike

Adrian Orr has moved interest rates up much faster than any other RBNZ governor before him. I had thought that Don Brash was really tough but Adrian Orr takes the cake. Was there any consideration to Sustainable housing? Seriously that is a No because most existing housing development projects have stalled or new projects been put on hold. There is no dual mandate.

LikeLike

Michael – I am also skeptical of the idea the mandate would have changed much over any horizon. For much of the 2010s I think the RBNZ, like many central banks, were grappling with understanding where interest rates were going given there had been such a significant expansion in monetary stimulus during the GFC but apparently low inflation afterwards. Their frameworks were always telling them that rates would need to ultimately rise and that inflation was just around the corner. Sometimes they saw indicators suggesting that was happening. A different mandate wouldn’t have changed any of that.

Having said that, I would not argue that a more activist monetary policy approach through the 2010s would have served NZ well.

Household debt to GDP was stable (uncharacteristically) and household debt to income actually fell a bit through the 2010s. Household balance sheets significantly strengthened and gave them the resilience to navigate the stresses of the Covid and post Covid period. It was useful the RBNZ didn’t interrupt that strengthening process by lowering interest rates even further. Indeed you can see that an inverse relationship between household debt to GDP and interest rates persisted through the period (and was very noticeable through the pandemic when policy was grossly over eased). When inflation is low and growth adequate there isn’t a case for overreaction. The public cares less about inflation when it’s below 3. Central banks should just leave them alone and get involved only if it looks like the output gap is moving significantly one way or another.

Inflation was low in the 2010s due to factors that were poorly understood but had little to do with domestic policy settings. Trying to offset whatever that was with lower domestic interest rates would have been damaging in my view. Asset prices and household debt would have risen by more causing increased societal strains and reduced household and financial stability resilience.

Right now the RBNZ should be solely focused on getting inflation to 2 percent. After that, if inflation is low and growth ok then that’s a quality problem. If there are concerns about per capita growth or living standards then other areas of government should do something. Cutting interest rates won’t help and will make things worse ultimately.

I have a couple of charts to illustrate my points but don’t think I can add them here.

Kelly

LikeLike

Thanks for those comments Kelly. I guess my problem with your suggested approach is that it wouldn’t have consistent with the explicit addition to the PTA in 2012 (addition of the midpoint, which all MoFs since have kept) and simply seems indifferent to unemployment (which a fair chunk of the public does care about, and which has real scarring effects on individuals). The approach you champion – and I know some other people who do so – ends up being functionally an argument for a “dual mandate”, but it is also not really consistent with the sort of accountability model explicit in successive RB Acts. That might not be the worst thing in the world, except that in practice it means allowing even more discretion to officials (who in the NZ case have simply not been excellent or commanding of respect). If I really thought that much additional discretion was macroeconomically appropriate I’d say Paul Tucker’s criteria for delegating power could then never be met and that the powers should be reserved to MoF herself (advised of course by the Tsy and RB, but as advisers not deciders).

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think anywhere between 0 and 3 over reasonable periods of time is fine. And I think the previous PTAs could have been interpreted consistent with that. If an output gap opens up as unemployment rises too far then of course act. Otherwise I think the Central bank causes more trouble than it’s worth. 20% up on asset prices so inflation maybe rises half a percent when unemployed is within cooeee of average/neutral is a bad trade off I think.

LikeLike

Of course by conventional estimates there was still a negative output gap in NZ during the first half of the 2010s.

But the big difference between us prob turns on the extent to which mon pol should be factoring on house prices/household debt outcomes (beyond any aggregate demand effects). I think it was a mistake to do so in Sweden and Australia, and led us slightly astray here at times when Governors became particularly angsty about house prices (altho in fairness here mostly a search for tweaky tools or regulatory (incl prudential regulatory) interventions.

LikeLike

It’s simple – you cannot have two simultaneous targets. Only in fiction does the cowboy shoot with two hands simultaneously and the archer loads two arrows on his bow. It is true for our eyesight which has a very small central and large peripheral vision and our brain is the same – only capable of really concentrating on a single idea. True with bringing up children too; my brother insisted his daughters cleaned their teeth and however exhausted they might be they would clean their teeth even with eyelids drooping before collapsing into bed; all my brother’s other requests were more hit or miss but that was his top priority. Just one target and you might be successful. Bringing up children is far more important than any central bank and its policies. So keep it really simple and give them a single target. Also remove all distractions such as their attempts at public relations, climate change, multi-culturalism and diversity.

LikeLike

Quite like the teeth-brushing story but…..when raising my kids I had multiple objectives for them (or for my parenting).

Entirely agree though on the final sentence, altho not because i think those things really distracted the RB from inflation, as because if bureaucrats are given a great deal of discretionary power they should use it only for the thing Parliament asked them to do, not to pursue extra personal agendas.

LikeLike

Cindy Ardern introduced us to the Four Cults of the Apocalypse – Covid, Climate, Treaty, and Trans. Obviously, over the past few years, Mr. Orr got stuck into these tasks, boots and all.

The Covid Cult saw Mr. Orr losing $12bn in the worst trading performance seen since Nick Lesson. The Climate Cult saw him howling up at the Sun God during random conferences. The Treaty Cult saw him singing waiata and preaching Karakia to the forest God. I’m not sure if he donned his finest frock to celebrate the Trans Cult, and shrieked at the stars in celebration, but I wouldn’t be surprised…

Do we want Mr. Orr to focus on the Covid Cult? NO. Do we want Mr. Orr to focus on the Climate Cult? NO. Do we want Mr. Orr to focus on the Treaty Cult? NO. Do we want Mr. Orr to focus on the Trans Cult? NO.

Should Mr. Orr instead be targeting household debt?

How about NO.

What about if Mr. Orr targeted house price inflation?

What about if he doesn’t. NO!

What about Mr. Orr being put in charge of achieving full employment?

NO, NO, and NO.

Mr. Orr has one job. 2% inflation.

He has failed dismally to achieve this target for years. Excuses are no longer acceptable.

LikeLike

[…] Unconvincing […]

LikeLike

If the RB has dual mandates,how about changing that to multiple?

Perhaps the balance of payments, exchange rates and productivity need adding to the remit?

Big flat screen TV s and big government regime versus exports , productivity relying on the exchange rate levels.

In fact the NZD level has a huge impact on profitability and growth in the tradable sector and profligacy in the consumer consumption that has tp be paid for.

The NZD is another ,much abused by Government ,tool which is used ,along with inflation (see Friedman ) to redistribute wealth .

No, The RB must focus on the one thing they can influence inflation

LikeLike