It doesn’t seem to have been the best week for the Reserve Bank since the release of the latest Monetary Policy Statement last Wednesday. Of course, one could make a pretty compelling case that in the Orr years few weeks have been, and especially not any weeks when Bank figures actually say or do anything. But for now we’ll focus just on the last week.

On the one hand there was some pretty clear pandering by the Governor to the instincts and preferences of the new government. There is nothing like losing $12 billion dollars of taxpayers’ money and delivering several successive years of core inflation well above target – with no contrition on either count – to suggest past loss of focus and energy, but we learned from the Herald that

The PM said that during his conversations with Orr on Tuesday he was pleased to hear the governor’s “obsession” with lowering inflation.

If that was really Orr’s word – and it isn’t entirely clear from the story whether it was his word or the PM’s take – and he really meant it (as distinct from just indulging in loose rhetorical pandering) it would be more than a little concerning, when central bankers (New Zealand and abroad) have been at pains for decades to explain that having an inflation targeting regime does not mean they are (in their own words) “inflation nutters”. There are many many examples, in formal literature and less, from here and abroad, but as just one local example this article from Orr’s time as the Bank’s chief economist back in the (allegedly hardline, but always actually quite flexible) Brash years. I don’t think Orr was actually serious about the “obsessive” bit, because when he was asked about inflation in the MPS press conference he was at pains to explain – sensibly – that if there were forecasting errors around how quickly inflation comes down they simply couldn’t be sensibly corrected immediately (lags and all that). But it speaks of a Governor who is simply not a nuanced and serious communicator (consistent with the near-complete absence of speeches from him on monetary policy, through a period of serious policy failures).

In his remarks last week Orr also seemed to be getting on side with the government’s stated intention of legislating to restore the statutory goal for monetary policy to price stability, noting that the Bank’s own work on the Remit review had suggested a more prominent place for the price stability goal. That was all fine, and Orr has been pretty clear all along that Labour’s change to the goal in 2018 had not made any material difference to monetary policy decisions in the last few years, and the Bank – under successive Governors (and chief economists) – has long championed its (internationally standard) flexible inflation targeting approach.

But then the current chief economist was let loose and in remarks to Newsroom is reported under this headline

as having said

which is an astonishingly loose comment from someone paid hundreds of thousands of dollars a year and holding a statutory office as an MPC member. It is no doubt true that one could set up a highly-simplified model in which some arbitrarily chosen reaction function to some specific types of shocks might end up with (temporarily) higher unemployment under one specification of the statutory target than the current one. But….not only would there be other shocks in which unemployment would be (temporarily) lower (when both inflation and unemployment are low), but there is no sign of any work or thought on whether such shocks are at all frequent, or how they were actually dealt with under the statutory goal in place here for the best part of 30 years. And, notwithstanding Conway’s comment, the monetary policy decisions that matter are almost never easy, precisely because they are about uncertain futures. Take the last time core inflation was well away from the target midpoint – in 2008 – and check how many times the Reserve Bank was tightening then. It wasn’t, of course, and was right not to have done so (whatever mistakes it (we) might have made in the previous couple of years). It might be interesting for someone to OIA the Bank and ask what evidence they have for Conway’s claim that the planned legislative amendment will result – even “at the margins” – in higher unemployment.

But all that was general high level policy frameworks stuff. What about actual policy and outlook.

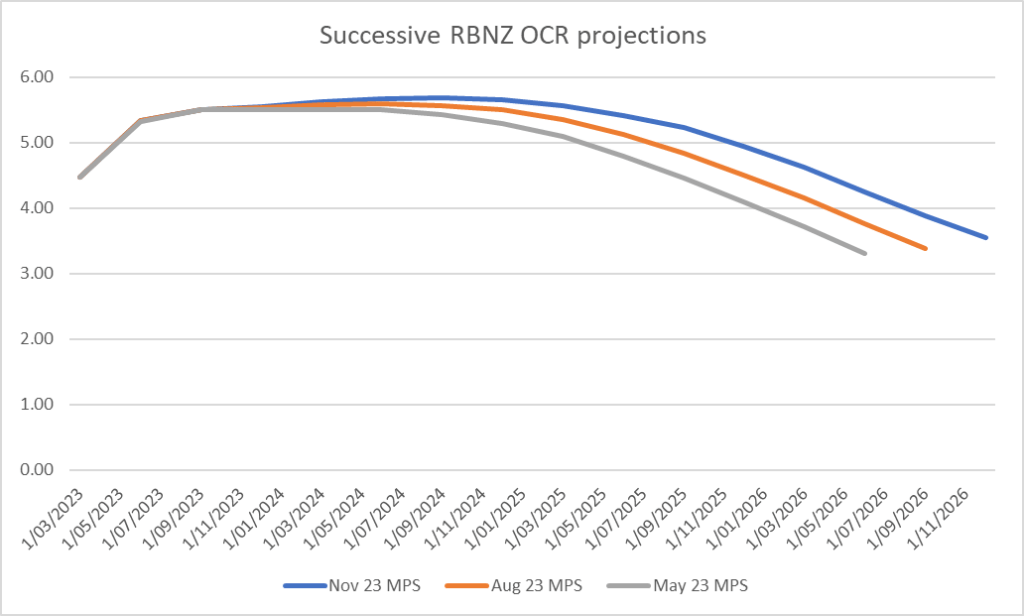

In the MPS – which the Governor described as “a wonderful wise document” – the Reserve Bank again revised upwards their future track for the OCR, lifting both the peak of the track (to the point where they reckon there is a better than even chance of another OCR increase next year) and increasing quite materially the extent to which they expect interest rates will have to stay high. The further out projections have been lifted by about 50 basis points, coming on the back of similar increases at the previous MPS.

But here is the most immediate problem (from a tweet last week).

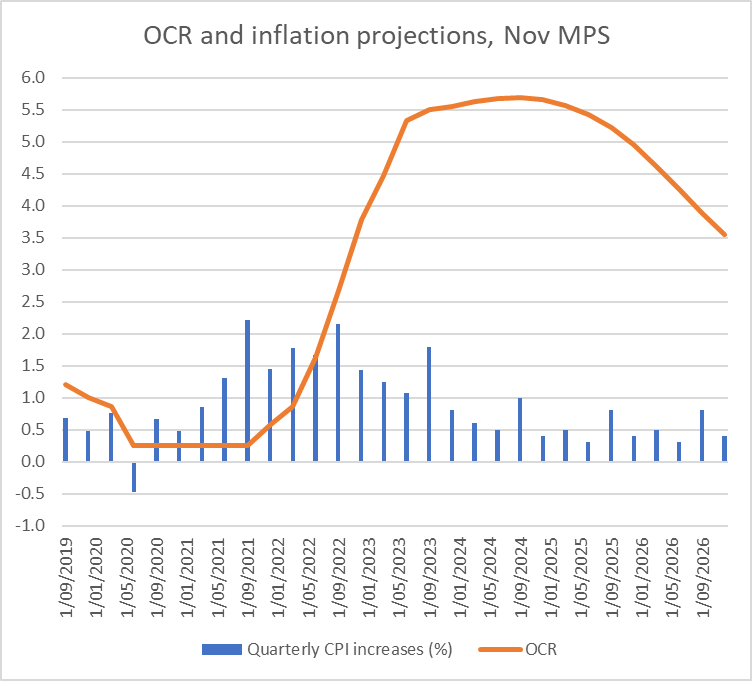

Much of the media comment focuses on annual rates of inflation. The Reserve Bank projections have annual inflation finally dropping into the target 1 to 3 per cent range – although still a considerable way from the 2 per cent midpoint the Bank is required to focus on – for the year to September 2024. Even that isn’t far away now, but in thinking about policy it is typically more useful to be looking at the projections for quarterly percentage changes in the CPI.

There is some seasonality in the CPI (September quarters are typically much higher and the other quarters a bit lower than average). Unfortunately the Reserve Bank does not publish its inflation forecasts in seasonally adjusted terms, but on this occasion eyeballing does fine. You can see not only that ever quarter in 2024 has quarterly inflation at about half what it was for 2023, and as early as the June quarter of next year (mostly measured as at mid May, so only five months away) the headline quarterly CPI increase is projected to be already 0.5 per cent. By the December quarter of next year, the quarterly CPI increase is explicitly consistent with annual inflation of 2 per cent.

And how long does monetary policy take to have its largest effects? Views differ but the standard Reserve Bank line – the reason why the Governor suggested that if they are wrong about September 2024 they can’t sensibly immediately fix things – is something like 18 months. Even if it is as short as 12 months, those inflation outcomes next year in the Bank’s projection are the result of the current OCR, not a possible increase next year. And those outcomes are entirely consistent, on a quarterly basis by next November at the latest, with the midpoint of the inflation target range.

So why would you publish projections now showing a further OCR increase next year, and no cuts below the current 5.5 per cent until mid 2025 when (a) your best projections (presumably) are that quarterly inflation will be at target next year, and (b) your routinely repeated view is that monetary policy takes perhaps 18 months to have its main effect on inflation? If anything, that looks like a recipe for keeping the unemployment rate – not expected to peak, at above 5 per cent until mid 2025 – a bit higher rhan otherwise “at the margin”.

One possibility was that it was all just about “jawboning”. In the MPC’s view markets were getting a bit over-enthusiastic looking for the first rate cut so perhaps the track was pushed up and out a bit to send a message (and yes, late messaging changes to interest rate tracks do happen). But…..even if that had been the case, why wouldn’t you also have pushed up the inflation track? After all, the Reserve Bank’s inflation projections (see chart above) show a really sharp collapse in quarterly inflation rates, starting right about now.

But two members of the MPC have been sent out to assure us, via different media outlets, that no, the Reserve Bank was dead serious, and it was not (in a Post article reporting comments from Conway) “talking tough for effect”, or (in a Herald interview with the Deputy Governor) that there were no games going on and “our messages are genuine”.

If genuine, then incoherent. If inflation is doing anything like what the MPC’s own published inflation projections are suggesting (ie very quickly now getting back to target), there is no credible case for keeping the OCR well above (assumed) neutral for the indefinite future, and not cutting at all until mid 2025.

(To be clear, I am not and never have been a fan of published central bank interest rate projections, or any medium-term central bank forecasts – the state of knowledge is so limited that anything is more about messaging and game playing than any real information – but it is the MPC that chooses what it publishes.)

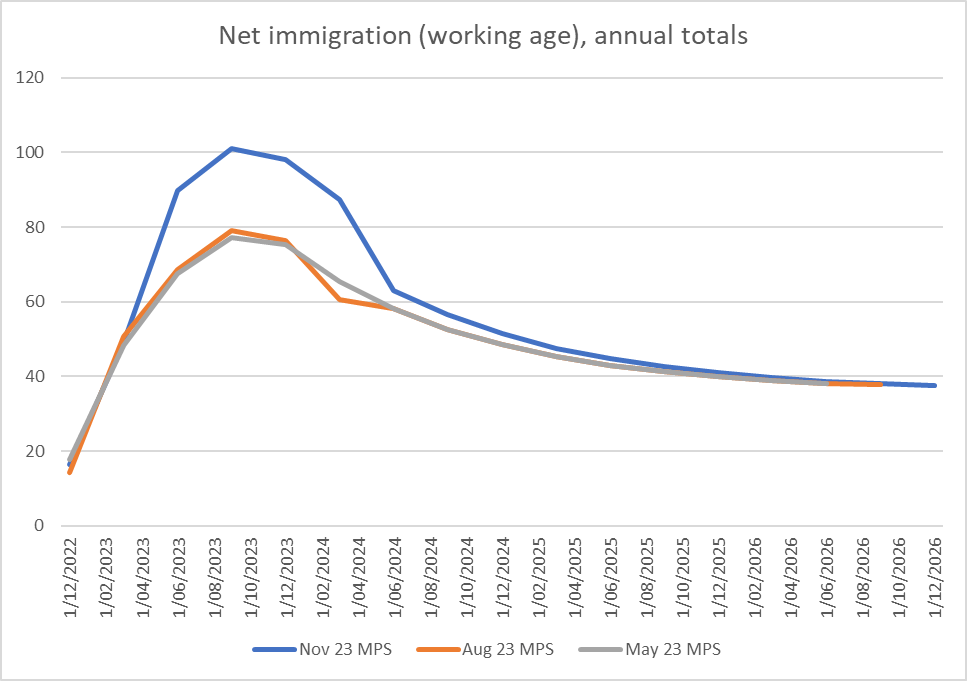

The story really doesn’t add up. Nor is it particularly compelling to suddenly start playing up fiscal pressures on demand (nothing having changed on the expansionary side around fiscal policy settings since the May Budget, and the Governor repeatedly played down demand effects in May and August – when it suited the government of the day for him to have done so). One could say something about immigration pressure (when the huge surge in net non-citizen arrivals has been evident for many months) altho the near-term estimates of the inflow have been increased.

But that big shock – the additional net arrivals – has already happened (quarterly this year), and yet the MPC tells us the think the inflation rate is just about to collapse, on current monetary settings.

Up to this point I have not taken a view on whether the Reserve Bank’s inflation forecasts are likely, just highlighting the tension between what are really quite rosy inflation projections, and that OCR forecast track – and the rhetoric- which is anything but.

The Reserve Bank has also been at pains to make the (obvious) point that they have to set monetary policy in the light of the New Zealand inflation outlook and that whatever is going on in other countries is not necessarily a great guide to what will be required in New Zealand. Which is all true, but…..much of what has gone on around inflation in the last three years has been fairly common to a whole bunch of advanced countries. There were, of course, the largely common supply shocks – ups and downs of oil and freight prices etc – but more importantly excess demand pressures, and extremely stretched labour markets, also became apparent in many countries. And if our fiscal policy looks to have been a bit more expansionary than in most, the biggest demand effects of that seem set to have been in 2022 and 2023 rather than beyond. The surge in immigration has certainly been huge – and my standard model for a decade has emphasised the positive net short-term demand effects from migration but (a) similar things have been seen in Australia and Canada, and to a lesser extent in countries like the UK, and (b) the Bank’s forecast assume quite a sharp slowing (annual net immigration next year is forecast at half the rate of this year.

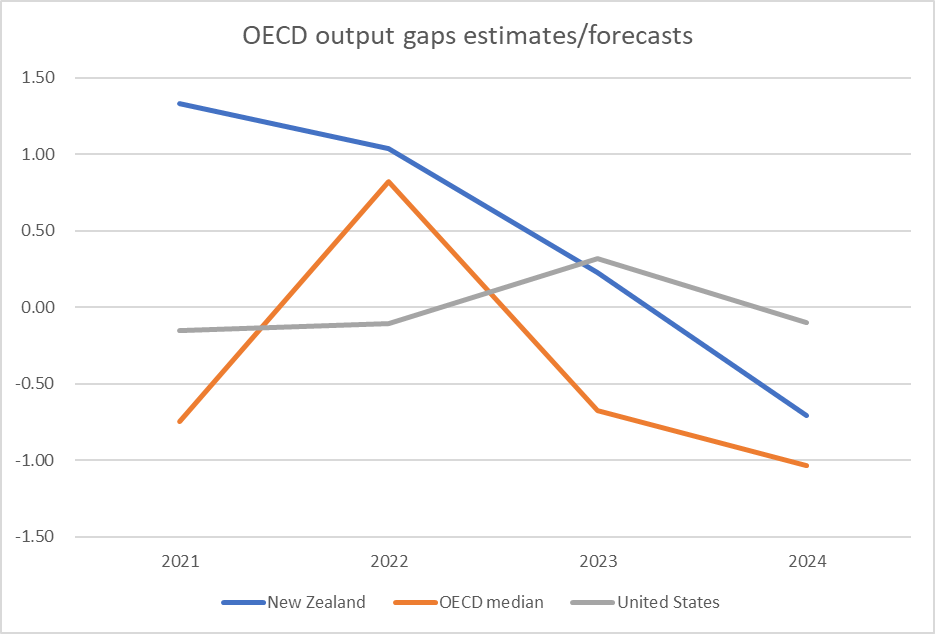

In a post a few weeks ago I highlighted that on IMF estimates New Zealand had had the biggest excess demand (positive output gap) problem of pretty much any advanced country. If so, that would be a reason for caution, why inflation might be tougher to beat here than elsewhere (and it is true that our OCR is only around those of other countries, whereas in most past cycles it has had to go higher). But the OECD’s recent forecasts, out last week, suggest a picture that has New Zealand’s experience closer to the pack for this year and next.

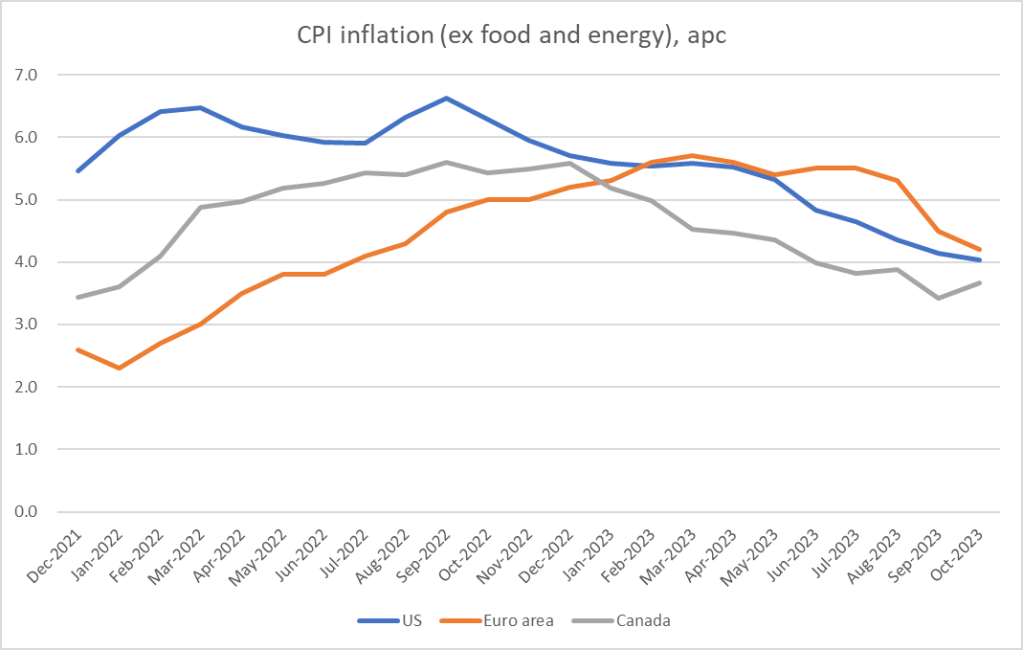

What has happened then to (core) inflation in other advanced economies?

There are positive stories (US and euro area getting a fair number of headlines)

Each of those current annual inflation rates are materially below New Zealand, and the quarterly/monthly data are often more favourable.

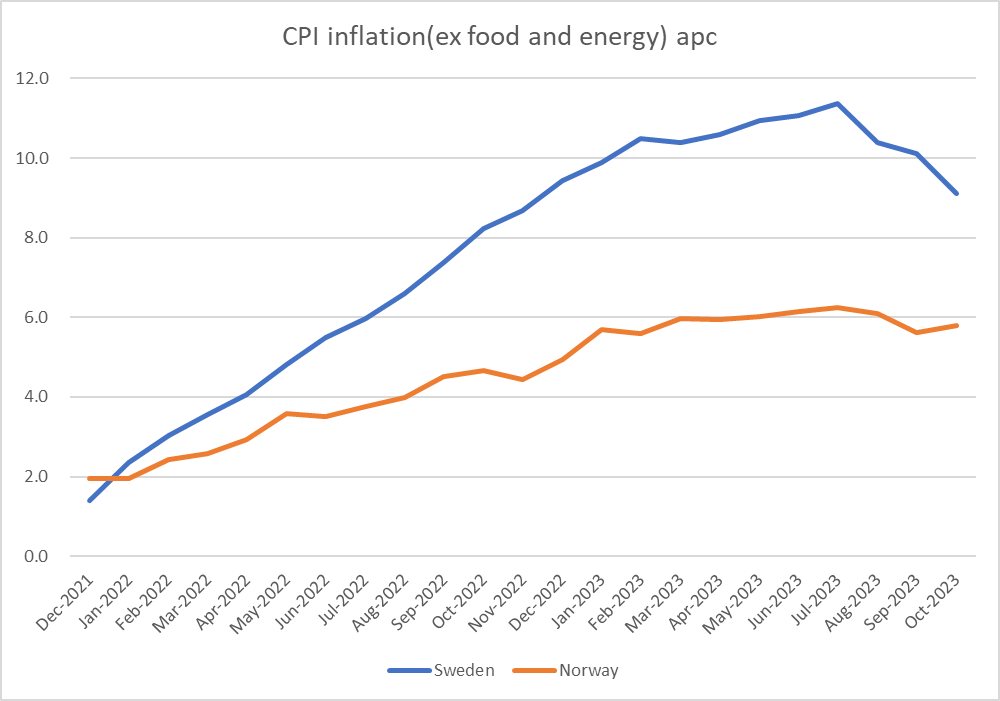

In the Nordics, perhaps a mixed picture

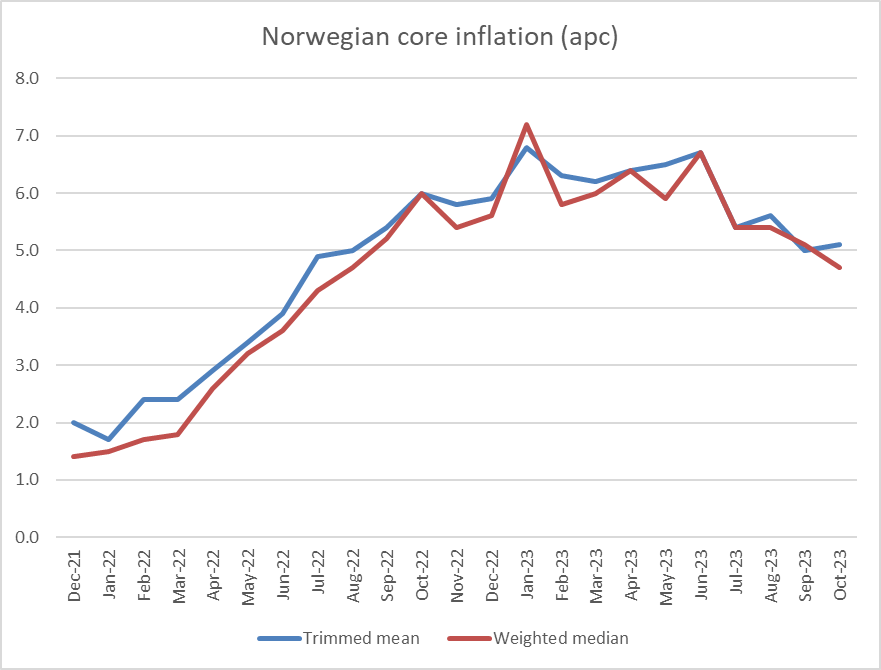

but even then if one looks to the Norges Bank’s core indicators things seem to be heading in the right direction.

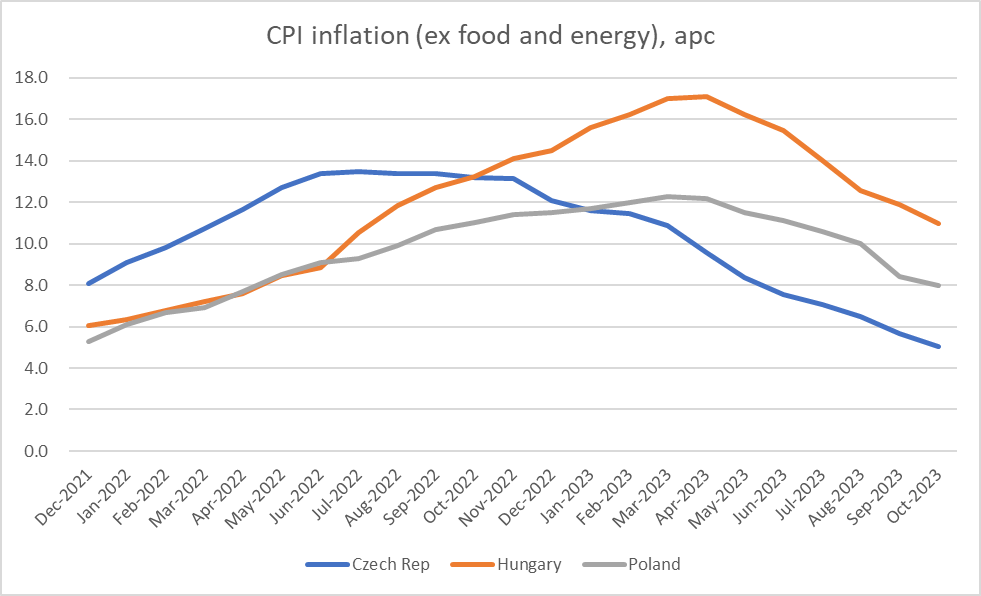

And even in the central European countries there has been a big reduction in core inflation (with a long way to go)

None of this is any guarantee that any of these countries will get to 2 per cent quickly, but the direction seems pretty clear, and it isn’t really obvious why it would suddenly become so much harder to cover the last mile. Nor, thus, is it really apparent why things will prove so much different here – when the RB itself tells us they think inflation is just about to collapse. It wasn’t as if there was any serious sustained analysis in the MPS itself to explain a) why the Bank expects inflation is on the brink of collapsing, or b) why they are really reluctant to believe their own numbers. Sure, the Governor was heard to mutter things about inflation expectations – even, bizarrely, suggesting that 10 year ahead numbers were some sort of personal blow, when we know the Governor will be gone in 4.25 years at most – but the best predictor now would have to be that if headline and core inflation fall away sharply, as the Bank tells us it expects, survey measures of inflation expectations will follow.

The Bank was in a slightly awkward situation last week, as neither they nor anyone else yet had (or has) a good sense of what the new government’s fiscal policy will mean (fiscal impulses etc) but that is no excuse for such an unconvincing set of stories on the data and evidence they do have. And of course now they have gone for the summer, with no speeches, no serious supporting analysis, just those strange plaintive lines from Messrs Conway and Hawkesby “no really, we are serious…..we really think inflation is to fall like a stone next year and yet we really think the OCR will have to stay this high or higher for the next 18 months”. It reflects poorly on the Bank, and should be just another set of evidence around the weaknesses of the Bank that one can only hope Nicola Willis will in time do something about.