The CPI for the December quarter was finally released yesterday – even later in the month than that other CPI laggard the ABS. The picture wasn’t pretty, even if at this point not particularly surprising. My focus is on the sectoral factor model measure of core inflation – long the Reserve Bank’s favourite – and if, as my resident economics student says “but Dad, no one else seem to mention it”, well too bad. Of the range of indicators on offer it is the most useful if one is thinking about monetary policy, past and present.

Factor models like this provide imprecise reads (subject to revision) for the most recent periods – that’s what you’d expect, especially when things are moving a lot, as the model is looking to identify something like the underlying trend. The most recent observations were revised up yesterday, and the estimate for core inflation for the year to December 2021 was 3.2 per cent. That is outside the 1-3 per cent target range (itself specified in headline terms, although no one ever expected headline would stay in the range all the time).

It is less than ideal. It is a clear forecasting failure – which would be even more visible if we show on the same chart forecasts from 12-18 months ago.

But…it isn’t unprecedented. In 28 years of data, this is the third really sharp shift in the rate of core inflation – although both were in periods before this particular measure was developed. And, at least on this measure, at present core inflation is still a bit below the 3.6 per cent peak in 2007, or the 3.5 per cent the annual inflation rate averaged for a year or more in 2006 and 2007.

What perhaps does stand out is how little monetary policy has yet done, how slow to the party the Bank has been. Over 1999 to 2001, the OCR was raised 200 basis points. From 2004 to 2007, the OCR was raised 300 points. And as core inflation fell sharply from late 2008, the OCR was cuts by 575 basis points.

So far this time the OCR has been increased by 50 basis points, and is not even back to pre-Covid levels – even though, on this measure, core inflation never actually dipped in 2020. I refuse to criticise the Reserve Bank for misreading 2020 – apart from anything else they were in good company as forecasters – but their passivity in recent months is much harder to defend.

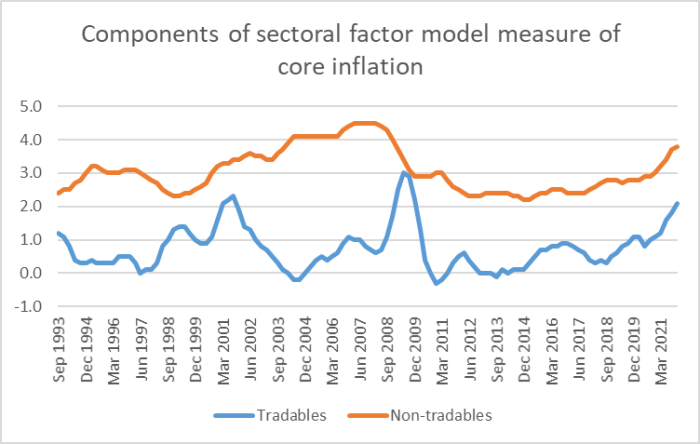

The sectoral factor model measure is itself made up of two components. Here they are

Because the model looks for trends, the big moves in this measure of core tradables inflation have often reflected the big swings in the exchange rate – which affects pretty much all import prices – but this time there has been no such swing. Just a lot more generalised inflation from abroad (as well as the one-offs that this model looks to winnow out). So a lot more (generalised) inflation from abroad – not something to discount – and a lot more arising from domestic developments (demand, capacity pressures, and perhaps some expectations effects too). It is a generalised issue – above target, and probably rising further (both from the momentum in the series, and continued tight labour markets and rising inflation norms).

The headline inflation number gets media and political attention it doesn’t really warrant. Headline inflation is volatile, and even if in principle it might be more controllable than what we see, it usually would not make economic sense to control it more tightly. For that reason, in 30+ years of inflation targeting it has never been the policy focus.

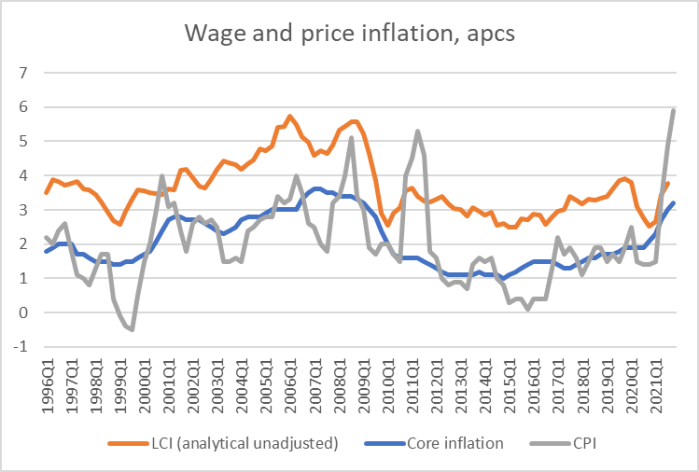

And to the extent that wage inflation fluctuates with price inflation, the relationship is much closer with core inflation (we’ll get new wages data next week, and most likely the annual wage inflation will have risen a bit further).

It is worth noting – for all the headlines – that in every single year of the last 25, wage inflation has run ahead of core (price) inflation. As it has continued to do even over the last year. That is what one would expect – productivity growth and all that – even if the economy were just growing steadily with the labour market near full employment.

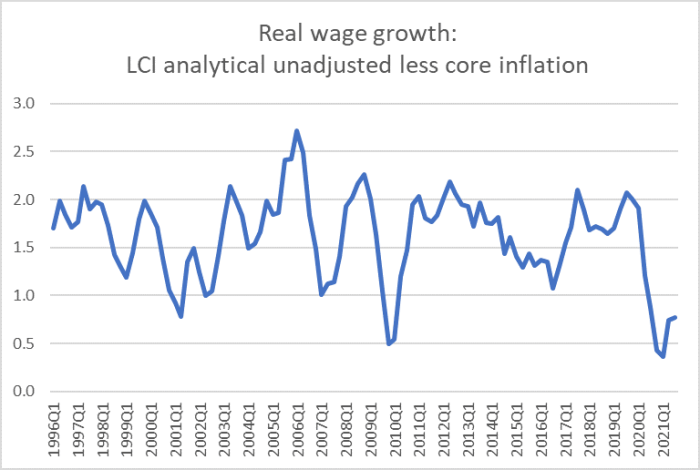

It is true that the gap between wage and price (core) inflation is unusually narrow at present

Perhaps the gap will widen again over the coming year – overfull employment and all that – but bear in mind that true economywide productivity growth is probably atrociously (partly unavoidably) low at present, so the sustainable rate of real wage growth is also less than it was.

(None of this means wage earners aren’t now earning less per hour in real terms than they were a year ago, but that drop is, to a very considerable extent, unavoidable. The gap between headline and core inflation is typically about things that have made us poorer, for any given amount of labour supply.)

What does all this mean for policy? First, for all the criticism – often legitimate – of wasteful and undisciplined government spending over the last two years – core inflation is primarily a monetary policy issue, and sustained core inflation above target is a monetary policy failure. The government is ultimately accountable for monetary policy too, but if what we care about is keeping inflation in check, it is the Bank and the MPC that should primarily be in the frame, not fiscal policy. Monetary policymakers have to take fiscal policy – just like private behaviour/preferences – as given.

To me, the recent data confirms again that the Reserve Bank was far to slow to pivot, and far too sluggish when they eventually did. They are behind the game, as was clear even by November before they – like the government, but even longer – went for their long summer holiday in the midst of a fast-developing situation. It is pretty inexcusable that we will go for three months with not a word from the MPC, even as inflation has surged in an overheating economy.

What disconcerts me a bit is the apparent complacency even in parts of the private sector. (If I pick on the ANZ here it is only because they put out a particularly full and clear articulation of their story quite recently). As an example, ANZ had a piece out last week suggesting that the OCR would/should go to 3 per cent by about April next year, but that this would/should be accomplished with a steady series of 25 basis point adjustments. I’m also hesitant about making calls about where the OCR might be any considerable distance into the future (and in fairness they do highlight some of the uncertainties) but if you are going to make a central-view call like that most people might suppose it was consistent with a gradual escalation of capacity pressures, gradually leaned against with policy. But on their own description, the economic growth outlook over the next year doesn’t look spectacular at all – the word “insipid” even appeared – while the pressures (inflation and capacity) seem very real right now, in data that (at best) lags slightly. Core inflation has (unexpectedly) burst out of the target range, the economy is overheated, inflation expectations have risen (even in the last RB survey the two-year ahead measure was 2.96 per cent – up 90 points in six months, when the OCR has risen only 50 points. ANZ’s economists did address the possibility of a 50 basis point increase next month. They seemed to think it unlikely, because no ground has been prepared. They may well be right about that – and that may be what their clients care about – but, as advisers, they seemed unbothered about it. Why not urge the Bank to get out now and prepare the ground for next month’s review? Why not thrown caution to the wind and suggest the world wouldn’t end if the MPC actually took the market by surprise and took actions that increased the changes of keeping inflation in check? Based on what we know now, the economy would be better off if the Bank raised the OCR by 50 basis points next month (and sold some of that money-losing bond stockpile) and suggested it would be prepared to do the same again in April if the data warranted.

What difference does is make? The big risk right now is that people come to think that a normal inflation rate isn’t something near 2 per cent, but something near 3 per cent (or worse). If that happens – and no single survey will tell the story – it will take a lot more monetary policy adjustment (and lost output) at some point to bring things back to earth, all else equal. And whereas we have no real idea what monetary policy should be in the middle of next year, it is quite clear that considerably tighter conditions are warranted now, and that the Bank so far has not even kept up with the slippage in inflation and expectations.

What about Covid? By 23 February when the MPC descends from the mountain top, it seems likely that we might be nearing the peak of the unfolding Omicron wave. Experience abroad suggests that even when the government doesn’t simply mandate it, a lot of people will be staying at home, a lot of spending won’t be happening. Who knows – and we may hope not – MPC members themselves, or their advisers, may be sick and enfeebled. Tough as those weeks might be, they should not be an excuse for a reluctance to act decisively. MPC went slow last year, and to some extent now pays the price in lost optionality. Delay in August didn’t look costly then. Delay now looks really rather risky.

But who are we to look to for this action. As (core) inflation bursts out of the target band, and expectations of future inflation rise, we already have an enfeebled MPC, even pre Covid.

- We have a Governor who has given few serious speeches in his almost four years in office,

- A Deputy Governor who didn’t greatly impress when responsible for macro, and is now likely to be focused on learning his new job, and finding some subordinates after he and Orr restructured out his experienced senior managers before Christmas,

- We have a Chief Economist who has been restructured out, and on his final meeting. No doubt he’ll give it his best shot but….that wasn’t much over the three years he was in the job, including not a single speech,

- And we have the three externals, appointed more for their compliance than expertise, who’ve given not a single speech between them in three years, and two of them are weeks away from the expiry of their terms (and no news on whether they’ll be reappointed or replaced).

It was pretty uninspiring already, to meet a major policy, analytical and communications challenge. And then yesterday, the dumbing-down of the institution – exemplified in speeches (lack thereof) and the near-complete absence now of published research – continued, with the appointment of Karen Silk as the Assistant Governor (Orr’s deputy) responsible for matters macroeconomic and monetary policy. And this new appointee – who it seems may not be in place for February – seems to have precisely no background in, or experience of, macroeconomics and monetary policy at all (but apparently a degree in marketing) But she seems to be an ideological buddy of the Governor’s, heavily engaged in climate change stuff. Perhaps the superficial customer experience – pretty pictures etc – of the MPS will improve, but it is hard to imagine the substance of policy setting, policy analysis, and policy communications will. It was simply an extraordinary appointment – the sort of person one might expect to see if a bad minister were appointing his or her mates. And if this appointment was Orr’s, Robertson has signed off on it, in agreeing to appoint her to the Monetary Policy Committee. It would be laughably bad, except that it matters. How, for example, is the new Assistant Governor likely to find any seriously credible economist to take up the Chief Economist position even if – and the evidence doesn’t favour the hypothesis at present – she and Orr cared? Coming on top of all the previous senior management churn and low quality appointments it is almost as if Orr is now not vying for the title “Great team, best central bank”, but for worst advanced country bank. (It is hard to think of serious advanced country central bank, not totally under the political thumb – and rarely even then – who would have such a person as the senior deputy responsible for macroeconomic and monetary policy matters: contrast if you will places like the RBA, the ECB, the Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, and numerous others.)

I sat down this morning and filled in the Bank’s latest inflation expectations survey. For the first time – in the 6/7 years I’ve been doing it – I had to stop and think had about the questions about inflation five and ten years hence (I’ve typically just responded with a “2 per cent” answer – long time away, midpoint of the target, 10 years at least beyond Orr’s term). With core inflation high and rising, policy responses sluggish at best so far, and with the downward spiral in the quality of the MPC (and the lack of much serious research and analysis supporting them), how confident could I be about medium-term outcomes. Perhaps it is still most likely that eventually inflation is hauled back, that over time core inflation gets towards 2 per cent, with shocks either side. The rest of the world, after all, will still act as something of a check, no matter how poor our central bank becomes. But the decline and fall of the institution is a recipe for more mistakes, more volatility, more communications failures, and less insight, less analysis, and fewer grounds for confidence that the targets the Minister sets will consistently be delivered at least cost and dislocation. That should concern the Minister, but sadly there is no sign it – or any of the other straws in the wind of institutional decline – does.

Im not too worried Mike.

The housing market is coming to a schreeching halt and as it slows we will see a sharp slowdown in CPI new dwellings, taking the heat off real estate agent fees and property rates in the process. Petrol price inflation will also dissipate, between them that will shave about 2.5pp off headline by year end.

Then a lot of the lift in the CPI elsewhere is in very large one off movements related to shipping issues, or border closure. International airfares, AV equipment, books, used cars etc. As supply normalises, which it will eventually, competition will correct these prices and some may even fall.

So inflation isnt going to become embedded. And if you dont believe my word, then you can look at TIPS which are hovering below 2% for the long dated 13 year contract.

And if im wrong, the Bank isnt in the same position it was in 95/96 or 06/07 as household debt levels are extrordinarily high, mortgage fixings very short and the mortgage curve is in contango. The RBNZ had households by the jugular. If needed, they can simply do 25bp every meeting until theyve ground (households) inflation into the dust.

I dont think it will get there and id be surprised if the cash rate rises beyond 2%. Business and consumer surveys suggest the white flags are already being hoisted…

LikeLike

Time will tell, but I’m reluctant to have policy run on medium term forecasts, when what we see out the window is so troubling (incl lower nominal rates than in Feb 20, but inflation expecs almost a full percentage point higher). It wouldn’t surprise if the OCR doesn’t get to 2 per cent – at all or for long – but my focus is on getting to 1.5% quickly and being pretty open-minded from there. What I do oppose is the Bank doing the ANZ thing, or the Wheeler 24 thing, and talking too confidently about where rates may need to get to in the medium term, something no one really has much idea on.

LikeLike

Michael, would it be fair to say that the RB’s human capital is the weakest it has ever been in the bank’s 88 year history? I can’t think of a single wise head or senior policy wonk there these days and I have been in the financial markets for 25 years (albeit 8 of those in Australia). My contacts at the RBA openly regard the RBNZ as something of a sick joke these days, which is sad.

LikeLike

Can’t say much about the first 30 years (when policy/analytical capability prob didn’t matter that much anyway), but if we took just the last 50 years that is certainly the way it looks to me. That said, some smart people in the past have made some really daft calls at time – I was part of some of them – and I recall a time perhaps 20-25 yrs ago when the RBA looked on us as crazed mechanistic zealots.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Utopia, you are standing in it!.

LikeLike

Hard to know what to say about all this. This Bank clearly never got the go-hard go-early message. Early was at least a year ago..

The RBNZ used to be noted for both style and substance. Sadly I do not see either any more – in spite of all the designation (and salary?) inflation in the management..

What on earth is the Board (not) doing??

LikeLiked by 1 person

Serving out their last few months while the chair (Neil) keeps sufficiently in with Adrian and MOF to effortlessly graduate to chairing the new, more powerful (on paper anyway) Board.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Couldn’t agree more. My prior point of the 50 being a bad idea last year due to swap volatility and horrendous interbank liquidity has been reversed. Sure it would have been a tricky time for the banks and the consumers would have worn the increased tranfer pricing but you are right; last year’s inaction in the face of genuine tightening signals for monetary policy, the opportunity was squandered and the “communication issues” where we got a no hike reduces the credibility of their actions. This is economics, not marketing spin. Looking at the swap curve over the next year, we can see the market is reluctant to price more than 25s for any meeting, and whilst there is a case for a 50, banks rest easy in the knowledge that the RBNZ is too spineless to make that move. What I do dread is when we do have serious economic headwinds and we are lagging behind the policy curve by such a margin that we are dealing to the previous crisis when the next one comes along.

On the OCR call; it was interesting to see that ANZ would put out a piece which was so heavily predicated on a central hypothesis which is forecasted so statically, it does not lend credence to the stochastic factors at play. With well defined economic conditions this research holds weight, however when we have so many variables and no cohesive government response to this, it is generous to think that one policy meeting can be forecast, let alone 6.

Additionally, this yo-yoing with OCR forecasts and the like just increases market volatility and that gets priced into mortgages where the rates have been oscillating unpredictably (to the consumer) which will erode consumer confidence.

LikeLike

Apart from the impact on households and business with the resultant (negative) flow through to government tax revenue, let’s not forget what a 225bps rise ( using the ANZ scenario) in the OCR means from a cash flow perspective to the Crown’s accounts on $52bio pool of floating rate debt.

LikeLike

“….but apparently a degree in marketing’. A little harsh? She is after all an Insead Alumni….

ahhh, but not of the highly competitive and prestigious Insead MBA programme. No, the four week Advanced Management Programme… which can also be completed two weeks on site and two weeks virtual. A bargain to your employer for $58k.

LikeLike

The Reserve Bank once generously paid for one of those sorts of programmes (at LBS) for me, altho in those days all four weeks were onsite. Memorable mostly for my one experience of rock climbing – in Kent of all places.

LikeLike

Kent & rock climbing not a natural association, apart from the White Cliffs of Dover -obviously. Tell me, does your CV indicate you are a LBS Alumni?

LikeLike

No

LikeLike

I like your transparency. Whereas putting ‘Almuni’ leans more towards inference and misdirection

LikeLike

I see that on her LinkedIn page it is clear that it is the Advanced Management Programme, so that spin and misrepresentation is clearly more at the RB end.

LikeLike

Yes, I was aware. My observations/comments are not a criticism of Karen Silk, but a rebuke of the Bank and its need to constantly spin things. In attempting to gild the lily the Bank hasn’t done her any favours right out of the gates, their clumsy comms just comes across as a somewhat hackneyed and blatant sales pitch. Perhaps your title could have been, ‘Inflation, Monetary Policy and all that…spin, again.’

Anyway good luck to her, with colleagues like these who needs enemies, and on past Assistant Governor survival rates …..I’ll give her a year.

LikeLiked by 1 person

On the subject of survival rates and comms let’s see what happens after the Bank’s performance at the December FEC.

Officials have placed themselves in all sorts of jeopardy in responding to questions raised about staff turnover. Officials oral responses to MP’s questions could have been brushed away as a simple ‘lapsus linguae’ and remedied by an appropriate written ‘erratum’. However, Assistant Governor Tainui-Hernandez came out with an emphatic “no, that’s not right”, which was promptly followed up by the Governor’s equally emphatic comment of “and yes its incorrect”…..this is unfortunate to say the least. The Bank then doubled down by sliding out a no fault no harm clarifying statement later in the day.

New Zealand State Services Commission’s Officials and Select Committee Guidelines are quite clear: “56 Witnesses or advisers who knowingly mislead a committee can be proceeded against by the House for contempt. In addition, committees have the power to receive evidence under oath, which leaves a witness who deliberately misleads a committee open to a charge of perjury under s 108 of the Crimes Act 1961”.

If the rumours I hear coming out of Wellington are true that ‘proceedings’ are being brought, and they probably should be by all sitting MPs in that Committee due to the affirmative rebuttals given and the need to uphold the sovereignty of Parliament , then it will get really interesting. As former Deputy Governor Bascand will ruefully know, protocols are protocols, and what’s good for the goose is good for the gander.

LikeLike

Interesting scenario (and a possibility Jenny Ruth touched on a couple of weeks ago). But wouldn’t Orr just (sensibly) respond with an abject written apology, citing “inexperience” (on Tainui-Hernandez’s part). The whole episode reflects poorly on the Bank (and Orr) but unless Grant Robertson does some sharp U-turn and starts actually caring about the decline and fall of the RB in the end it won’t come to much.

After all, these are people happy to appoint a marketing and customer experience exec to run the central bank’s macro/mon pol functions, and to appoint her to the MPC. And yet barely a murmur – incl from the Oppn or the media.

LikeLike

Yes, but Tainui-Hernandez is a well-qualified and experienced lawyer/barrister. From her earlier comments she clearly recognised the peril she was in, but stepped on the landmine anyway. It’s baffling- legal 101 and an exercise in getting the facts straight to a question you know will be asked (especially given the backdrop in the proceeding 24 hours). Hence why the opening stance and subsequent responses given by the Bank’s officials comes across as a deliberate attempt to mislead the Committee ……Unfortunately for them they just didn’t seemed to fully comprehend how serious it could be, but I doubt many people in the State Sector do either.

LikeLike

All fair, but still the issue remains that unless Robertson decides to change his stance there will be no real consequences. It isn’t as if Orr can simply jettison Tainui-Hernandez, when he was sitting right there and made effort to clarify or answer openly immediately.

Per your next response re Robertson, it prob would make some sense to cut Orr loose – or, for now, just distance himself from bad Orr choices – but to do that would open fresh questions about his own past stewardship judgement. Will be interesting to see how far the Nats pursue the Orr/RB issues, but Luxon forcing Bridges to backtrack before Christmas wasn’t encouraging.

LikeLike

Granted it would be hard for Roberston in his appointment of Orr to claim ‘non est factum’ in his defence, but as most Government Ministers everywhere barely read let alone understand half of what lands on their desk anyway perhaps there is precedent somewhere.

LikeLike

It is, and always will be, about political capital. Politically it may have suited Roberston to have appointed Orr as Governor and sing from, what he hoped would be, the same hymn sheet, but it’s become abundantly clear very quickly there is little harmony in that particular boys choir. Instead of Orr and the Bank being an asset they have become a ballooning liability to Labour with the Bank seen as a soft ( self imposed) target for National to indirectly attack Labour. Ultimately, this sniping is in nobody’s best interests, especially as noted previously when inflation is on the march and what is required of a Central Bank is to focus its efforts and energies on meeting its legislated mandate.

LikeLike

PBL

Totally agree with your last sentence.

Particularly at present when there is a need for courageous RB use of the OCR.

So far too little and too late.

When a team starts poking one another it is indicative of internal decay.

The stability of the NZD must be their focus not internal politics.

LikeLike

Sort of connected to this topic is a review of a new book, The Lords of Easy Money: How the Federal Reserve Broke the American Economy by one Christopher Leonard.

The review in the RealClearMarkets website is brutal, but when you get a chance I’d appreciate a post on it. I think he makes a lot of good points and certainly takes a hammer to my acceptance of the idea that it is cheap, easy money that has been largely responsible for a booming US stock market in the last twenty years.

LikeLike

I have the book on order – somewhat sceptically – so there may well be a post to follow. I certainly don’t buy the idea that central banks are to blame for share prices trends.

LikeLike

[…] disagreed and believed that monetary policy was responsible. I presume the interviewer had in mind my post from a couple of weeks back, and I then tweeted out this […]

LikeLike