In my post yesterday about the Reserve Bank’s FSR and the subsequent press conference conducted by the Deputy Governor I included this

The sprawling burble continued with questions about whether banks should lend more to things other than housing – one veteran journalist apparently being exercised that a large private bank had freely made choices that meant 69 per cent of its loan were for houses. Instead of simply pushing back and noting that how banks ran their businesses and which borrowers they lend to, for what purposes, was really a matter for them and their shareholders – subject, of course, to overall Reserve Bank capital requirements – we got handwringing about New Zealand savings choices etc etc, none of which – even if there were any analytical foundation to it – has anything to do with the Bank.

Someone got in touch about the 69 per cent line and suggested that it must be a sign of something being wrong, going on to suggest that the Reserve Bank’s capital framework and associated risk weights was skewing lending away from agricultural and (in particular) business lending.

My summary response was as follows:

I guess where I would come close to your stance is to say that if we had a properly functioning land market producing price/income ratios across the country in the 3-4 range (as seen in much of the US, incl big fast-growing cities) then the share of ANZ’s loan book accounted for by housing lending would be much less than 69%, and in fact the total size of their balance sheet would be much smaller. But my take on that is that the high share of housing loans is largely a reflection of central and local govt choices that drive land prices artificially high, and then we need financial intermediaries for (in effect) the old to lend to the young to enable houses to be bought. The fault isn’t the ANZ’s and given the capital requirements in NZ there is little sign that the overall balance sheet is especially risky, and therefore should not be of particular interest to the RB (except perhaps in a diagnostic sense, understanding why balance sheets are as they are). I’m (much) less persuaded that there is a problem with the (relative) risk weights, given that every comparative exercise suggests that our housing weights are among the very highest anywhere (and, in effect, rising further in October).

But to elaborate a bit (and shift the focus from one particular bank) across the depository corporations as a whole (banks and non-banks) loans for housing are about 62 per cent of total Private Sector Credit (and total loans to households are about 64 per cent). A large chunk of the balance sheets of our financial intermediaries are accounted made up of loans for housing.

The gist of my response was that that shouldn’t surprise us at all, given the insanity of the land use restrictions that central and local government impose on us, rendering artificially scarce – and expensive – something of which there is an abundance in New Zealand: land. If, from the perspective of the economy as a whole, relatively young people are buying houses from relatively old people (or from developers) the higher house/land prices are the more housing credit there needs to be on one side of banks’ collective balance sheets and – simultaneously – the more deposits on the other. If median house prices averaged (say) $300000 – as they do in much of the (richer) US – there would be a great deal less housing credit in total.

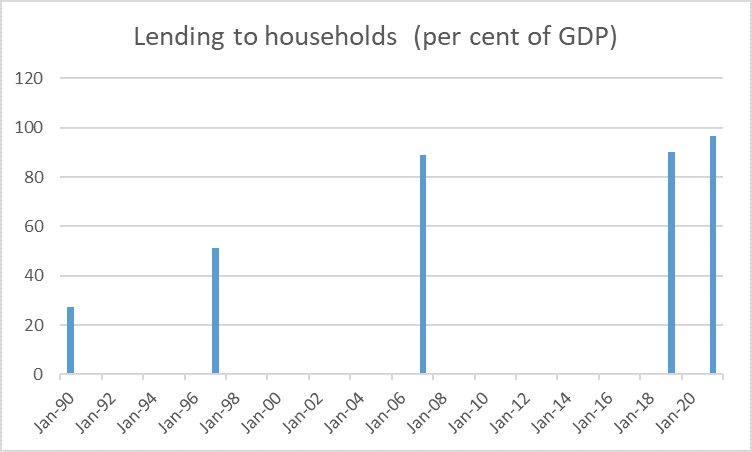

One other way to look at the stock of housing credit is to compare it to GDP – in effect, all the economic value-added in the entire country. Since the GDP series is quarterly and the credit data are monthly, I haven’t shown a full time series chart here. The data start from December 1990, and then only for an aggregate of housing+personal loans (but personal loans are small in New Zealand). So I’ve shown lending to households in Dec 1990, in mid-97 (roughly the peak of the business cycle), Dec 2007 and Dec 2019 (two more business cycle peaks), and March 21 (for which we have credit data, but only an estimate for GDP).

There was a huge increase in the stock of lending, as a share of (annualised) GDP over the first 17 years of the series. What I’ve long found interesting is how little change there was over the following full business cycle (there were ups and downs in between the dates shown), and then we’ve had a bit of a step up in the last year or so (and even if house prices stay at this level, future turnover will tend to further increase housing debt expressed as a share of GDP).

Since real house prices have more than tripled since 1990 it is hardly surprising the stock of housing debt (share of GDP) has increased hugely. Were real house prices to, for example, halve then we might over time expect to see the stock of housing debt drift gradually back – it could take decades – towards say the 1997 sort of number.

Implicit in the journalist’s comment was a suggestion that lending to housing somehow limits how much lending banks do for other things. That generally will not be so. Banks (as a whole) are generally not funding-constrained – not only do loans create deposits (at a system level) but international funding markets are available (and used to be very heavily used, when NZ had large current account deficits). Of course, there is only so much capital devoted to New Zealand banking at any one time, but in normal circumstances capital flows towards opportunities.

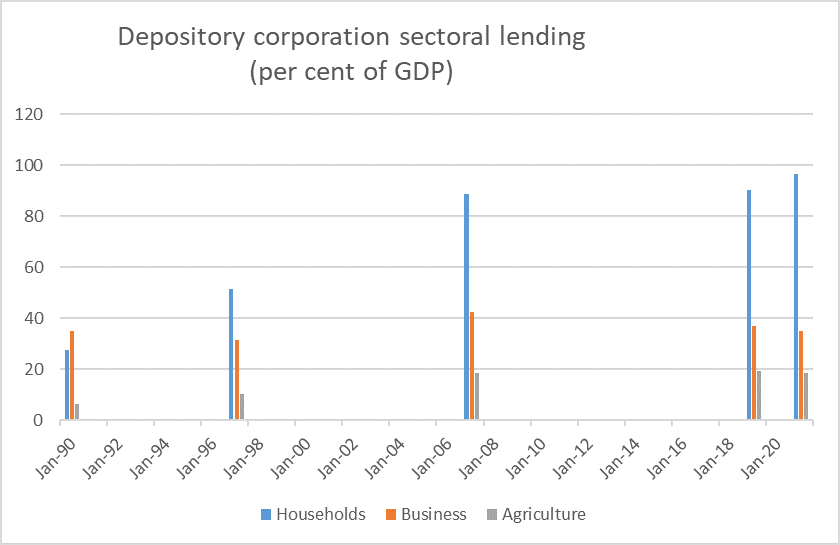

But what has the empirical record been? The Reserve Bank publishes data for business lending from banks/NBDTs (which isn’t all business borrowing by any means – between funding from parents and the corporate bond market) and for agricultural lending.

Here is how the full picture looks

For what it is worth, intermediated lending to business in March was exactly the same as a share of GDP as it was in December 1990. For younger readers, December 1990 was just a couple of years into banks working through the massive corporate debt overhang that had built up in the few years immediately following liberalisation. Farm credit, of course, has increased very substantially – again particularly over the years leading up to 2007/08 with the wave of dairy conversions and higher land prices.

On the business side of things, it is worth bearing in mind that business lending (share of GDP) was consistently weak throughout the last business cycle. Some will argue that banks had some sort of structural bias against business but even if so (a) over that decade or so there was no growth in the stock of housing lending as a share of GDP, and (b) there is little compelling evidence that systematic and large unexploited profit opportunities were going begging over that decade. It seems more likely that the markets – including banks – financed the profitable opportunities that were around, but there just weren’t many of them.

So my story remains one that if central and local government were to free up land markets and house price to income ratios dropped back to, say, 3-4 then over time the stock of housing debt (share of GDP) would shrink, a lot. There are some stories on which much cheaper house prices generate fresh waves of business entrepreneurship etc with workers able to flock to those opportunities, but I don’t find those stories convincing in New Zealand (in the aggregate). But simply repressing the financial system some more – the agenda the Reserve Bank and the government have been pursuing for several years now – will not change those business opportunities one iota.

(This post hasn’t tried to deal with the riskiness of the housing loans. My take on that is really the same as the Reserve Bank’s – at least when it isn’t champing at the bit to intervene. Capital requirements (and actual ratios) are high – materially higher than they were – and they are calculated in a fairly conservative way, with risk weights on housing that are fairly high, including by international standards. For what it is worth, the ratings issued by the agencies seemed aligned with that interpretation. )

That we have such a large share of total credit for housing isn’t, prima facie, a banking system problem – banks will follow the opportunities that (in this case) bureaucratic distortions create, and our central bank has demanding capital standards and in APRA one of the better banking regulators around – but rather just another indicator of how warped our housing market has been allowed – by governments – to become. But we knew that already. In fact, governments knew it to, but they prefer to try to paper over cracks, hide behind ever more pervasive RB controls, rather than tackle the core issue.

On which note, a couple of months ago the Wellington magazine Capital asked if I would contribute an article on what might be done to fix the housing market, with a Wellington focus. I wasn’t really familiar with the magazine – having previously seen it only in hairdressers, takeaway outlets and the like, for readers to glance through while they wait – but I said yes, and looking through the edition I picked up this week it looks like a mix of fairly geeky material (eg a whole article on lead-rubber bearings) and the lifestyle stuff.

Since I didn’t give them my copyright, many readers are out of Wellington. and the issue with my article seems to have been on sale for a while now here is the piece I contributed.

Free up the land: unravelling the unnatural housing disaster

Michael Reddell[1]

April 2020

New Zealand house prices, even adjusted for inflation, have more than tripled over the last 30 years. The persistent trend was unmistakeable even before the latest surges. Million-dollar houses were once the rare exception in Wellington, but now are almost the norm in too many suburbs. The Wellington region median house price is now perhaps 10 times median income, putting home ownership increasingly beyond the reach of an ever-larger share of those in their 20s and 30s.

Most of the talk is loosely about “house” prices but what has really skyrocketed is the price of land in and around our urban areas; whether land under existing dwellings, or potentially developable land. And this in a country with so much land that all our urban areas cover only about 1 per cent of New Zealand.

It is scandalous, perhaps especially because it is an entirely human-made disaster. Land isn’t scarce, and hasn’t become naturally much more scarce, even as the population has grown. Instead, central and local governments together have put tight restrictions on land use. They release land for housing only slowly and make it artificially scarce, not just in and around our bigger cities but often around quite small towns. And if there is sometimes a tendency to suggest it is “just what happens”, citing absurdly expensive (but much bigger) cities such as Melbourne, San Francisco or Vancouver, nothing about what has gone on is inevitable or “natural”.

The best way to see this is to look at the experience in the United States, where there are huge regions of the country – often including big and growing cities – where price to income ratios are consistently under 4. Little Rock, for example, is the state capital of Arkansas. It has a growing metropolitan population of just under 900,000, and a median house price of about NZ$300,000 – little changed, after allowing for inflation, over 40 years. The US also helps illustrate why it is wrong to (as many do) blame low interest rates: not only are interest rates the same in both San Francisco and Little Rock, but US longer-term real interest rates are typically a bit lower than those in New Zealand. The same goes for tax arguments: they have much the same tax code in both the high-priced growing US cities as in (much) more affordable ones. High real house prices are a policy choice; not necessarily the desired outcome of central and local government politicians, but the inevitable outcome of the land use restrictions they choose to maintain.

Both central and local government politicians sometimes talk a good game about making housing more affordable, but neither group seems to have grasped that in almost any market aggressive competition among suppliers is what keeps prices low. People sometimes suggest there isn’t enough competition among, for example, supermarkets or building products suppliers, but if we really want widely-affordable housing again in New Zealand what we need is landowners aggressively competing with each other to get their land brought into development. And that has to mean an end to local councils deciding where they think development should happen, whether within the existing footprint of a city or on its periphery. We need a presumptive right for owners to build, perhaps to two or three storeys, on any land (and, of course, councils need to continue to be able to charge for connecting to, for example, water and sewerage networks). It could be done now. That it isn’t tells us that councils are the problem not the solution. Too many – including in Wellington – seems to think it is their role to use policy so that in future lots of people are living in townhouses and apartments, even as experience suggests that what most (but not all) New Zealanders want, for most of their lives, is a place with a backyard and garden. And they seem to fail to understand that simply allowing a bit more urban density, perhaps in response to a build-up of population pressure, hasn’t been a path anywhere else to lowering house prices. Instead, such selective rezoning simply tends to underpin the price of those particular pieces of land.

Sometimes people suggest that even if this sort of approach would be viable in Hamilton or Palmerston North, it isn’t in rugged Wellington. But as anyone who has ever flown into or out of Wellington knows there is a huge amount of undeveloped land in greater Wellington. And if the next best alternative use should be what determines the value of land that could be used for housing, much of the land around greater Wellington simply does not have a very high value in alternative uses (not much of it is prime dairying or horticulture land). Unimproved land around greater Wellington should really be quite cheap, although the rugged terrain would still add cost to developing it to the point of being ready to build.

Some worry about, for example, the possibility of increased emissions. But once we have a well-functioning ETS the physical footprint of cities doesn’t change total emissions, just the carbon price consistent with the emissions cap. And for those who worry about traffic congestion, congestion charging is a proven tool abroad, which should be adopted in Wellington (and Auckland).

I’m not championing any one style of living. The mix between densely-packed townhouses and apartments on the one hand, and more traditional suburban homes on the other, shouldn’t be determined by the biases and preferences of politicians and officials but by the preferences of individuals and families, exposed to the true economic costs of those preferences. Similarly, policymakers should respect the (changing) preferences of groups of existing landowners what development can, or cannot, occur on their land.

The behaviour of councils over many years reveals them as, in practice, the enemies of the sort of widely-affordable housing which the market would readily provide (as it does in much of the US). If councils won’t free up the land, to facilitate the aggressive competition among land providers that would keep prices low, central government needs to act to take away the blocking power of local councillors.

And this need not be the work of decades. Of course, it takes time to build more houses, but the biggest single element of the housing policy failure is land prices. Once the land use rules look as though will be freed up a lot, expectations about future land prices will adjust pretty quickly, and prices will start falling. We could be the boutique capital city with widely-affordable housing. The only real obstacles are those who hold office in central and (especially) local government.

[1] Michael Reddell was formerly a senior official at the Reserve Bank, and also worked at The Treasury and as New Zealand’s representative on the board of the International Monetary Fund. These days, in additional to being a semi-retired homemaker, he writes about economic policy and related issues at http://www.croakingcassandra.com

Your summary of restrictive land-use policy being the cause of high house prices is of course 100% correct, and yet the question remains, why is this evidence (and there is plenty of evidence) ignored?

I have been at the coal face on land developments in Texas and NZ, and there is no reason why our housing should not be circa 4x median income, in fact, NZ’s housing right up until the early 90’s was always circa 3x median income.

One thing I have noticed is the Govt. with their increasing buy-up of private land for Kainga Ora, is buying that land at the present and historically highly inflated land values and is in effect locking these inflated prices more and more into the ‘norm’. that you have to pay.

This on top of material supply and labour constraints, climate change charges, plus building code upgrades is all adding to the cost. if we think houses are unaffordable now, then they only going up after these extra costs.

What used to happen when the restriction in the market was the buyer, ie less demand than supply, then the buyer set the price, which they obviously wanted to be lower. Thus based on this price, all other costs are deducted and what was leftover was the price you could afford to pay for the land, which if it was higher than its present use, might mean you could buy it. If not, then this represented less supply and balanced out the demand, the end result being that in a less restricted land market, developers and home buyers found an equilibrium between how cheap and the amenity value a buyer wanted and how cheap the developer could buy the land for, which meant the developer could buy land at slightly more than the raw rural land price and build, plus margin resulting in a house that was about 3 to 4 x median multiple.

I have run present NZ subdivision budgets through the same land policy arrangements as they do in the affordable US states, and it always comes out at about 4 x median multiple, it’s almost a universal law this will happen if you have a presumptive right to build.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Not only are they buying at historically highly inflated land values and in effect locking these inflated prices more and more into the ‘norm,’ they are paying for the land with deficit financed money indirectly created by the RB through its asset buying programmes.

LikeLike

Out of interest, would the growth in household debt relative to a measure of household income be more indicative of the problems faced by younger homebuyers? Just thinking all of GDP isn’t avaliable for servicing housing debt….

LikeLike

Oh, absolutely, This post was about a slightly different point though, so I just used GDP as a denominator as a scalar for the size of the economy.

The RB itself does analysis that tries to dig down and look at the incomes of those actually borrowing (itself more relevant than the total, given that most households either no longer have or have never yet had a mortage).

LikeLike

Hi Michael

It is Glenn Morris here from Nelson.

Re your latest post about land prices and so on.

I have the Tasman District Council and the Nelson city council talking at the Nelson Property Investors Association on the 1st June.

I have asked them to talk about intensification along with their LTP documents.

30 years ago when I was selling real estate in Nelson it was permissible to subdivided the old sections into 220m freehold lots to permit joined flats (home units) on them. Now the smallest size is 400m.

The NCC idea of intensification is to permit and encourage CBD owners to put dwellings on the second floor. Yet on my commercial property in lower Vanguard Street being about 50m from what they call the CBD I cannot do the same. Even further beyond my property multiple retail stores are operating such as Briscoes, Rebel Sports and so on. Goodness knows how they figured out where the CBD is.

Despite the NCC admitting they have run out of flat land they are not proposing to return to intensification that the government is encouraging / demanding they do.

The TDC has consented 600 dwelling in the year to March. That is a higher rate per 1000 people than Auckland and in fact higher than any other region in NZ. Every YTD for the last 12 months it has been around 550. Yet their latest LTP shows a forecast of 450 PA for the next 10 years and after then they must think the world is coming to an end and people are no longer having babies because they have dropped the forecast to an even lower level.

Is it any wonder with blind and death planners that my portfolio increased in value by $200,000 in April. It might have even been higher than that but 25% of the portfolio is commercial and Homes.co do not quote commercial properties.

Regards

Glenn

LikeLike

Thanks Glenn. Nice to hear from you, but what a depressing – but I fear all too typical – tale.

LikeLike

But even if they adapted to a 200 sqm intensification level, that ignores what actual home consumers might desire. The reality is that land is the scare resource, not houses. How many houses have been demolished and replaced, on the same piece of land. The land stayed the same, not the house.

Values other than the simple amenity value of the house come into play. Perhaps surprisingly to planners at least, consumers are not homogeneous, they place value on different attributes; kitchens, locations, views, schools etc. But the land is the same. It is not a surprise that a coincidence of these aspects tends to create pockets of relatively high value, e.g. Herne Bay in Auckland, Double Bay in Sydney, Central Park views in NY. Some of these areas are genuinely scarce in a land sense, unless you allow intensification. But not all consumers want intensification (and the planners despair).

Where I live in Auckland I am zoned for 3 dwellings per site (approx 1000sqm). 50m up the same street you can have triple that (at least). Why the difference? I am on a site that is already split into 3, dating back to the 1980s. So the urban plan for my site changed nothing. The relative change i.e. the permissiveness 50m away probably translated into a land owner gain (for them) as the total supply has only marginally changed relative to demand. I am thankful for that, my section is now scarcer and I await the next change to cash in.

Stupid people ignore consumer preferences and economics. Unfortunately they seem to be in charge of planning.

LikeLike

dutyfreenz, Auckland does not operate on roughly 3 dwellings per your 1000sqm site. This sort of measurement was under the old district plans that has been replaced by the Unitary Plan. The number of dwelling allowed is dependent on the size of your dwelling and number of carparks not the size of the land. The most common zoning is the Mixed Housing Suburban and a 1000sqm site typically allows for 8 terrace houses, 2 level buildings with a single carpark.

LikeLike

The size of the dwelling and the number of carparks is determined by you. Auckland Council does not require carparks in higher density developments under the Unitary Plan but does give itself the ability to veto designs.

LikeLike

Land supply is not the only housing supply restriction. The land-use infrastructure funding and financing issue should also be addressed. Infrastructure deficits (and the fear of them) are a major driver of local government behaviour. Michael I am sure as an economist you could come up with an incentive scheme to drive better LG behaviour?

Also not only would a functional ETS system that correctly charges for carbon emissions be required, road congestion and on-street parking needs to be dynamically priced to prevent gridlock.

View at Medium.com

LikeLike

Brendon, money does not grow on trees. Local Council is funded by ratepayers. The problem with Infrastructure is that it is hidden from view and therefore it is easier for Councillors to defer or ignore the maintenance or renewal costs required. It is really only when things start to break down that ratepayers have to stump up with cash. But by waiting till things breakdown the cost becomes enormous. Central government has been ignoring the fact that existing ratepayers do not have the means nor the inclination to fund infrastructure costs especially with the income to debt limits placed on local councils.

This is why income to debt limits make no sense especially when interest rates are so low.

LikeLike

Thanks Brendan. Certainly keen on congestion pricing in our larger cities.

LikeLike

“Certainly keen on congestion pricing in our larger cities”

I kind of understand having off-peak public transport pricing but applying that as a general principle to private motorists, presumably with some form of toll or surcharge… seems more controversial – is that what you are suggesting? It sounds potentially regressive and punitive in its effect. As the city continues to grow and congestion worsens do the fees increase?

A functional roading infrastructure is an essential requirement of any modern city, paid for with taxes, so it is not clear to me why even more taxes should be levied to dissuade use. Unless, perhaps, the tax were temporary and directed entirely towards a roading project that improved traffic flow and mitigated congestion.

LikeLike

Not clear to me why roads need to be paid for by taxes, as distinct from user charges, but I’m quite attracted to the model in which central city congestion charges generate revenue which is returned to all residents of the respective cities in an equal lump-sum annual payment. Since those working in the centres of our cities tend, on average, to be higher paid than average, and those driving in (rather than public transport) also tend to be higher income on average it isn’t obviously a regressive model. Also a congestion charging regime would support more economic pricing of public transport, thus fewer direct subsidies needed.

LikeLike

Roads are already paid for by user charges in the form of the excise tax for petrol per litre (+GST+Local Authority taxes) and road user charges for diesel, quite hefty amounts. Adding yet more taxes to the use of critical infrastructure just reduces efficiency and competitiveness.

I can’t imagine a time when local or central governments would ever return taxes to taxpayers in this way, unless forced to – they will just spend any windfall on other projects.

The comments on the incomes of people driving… seems overly generalised and stereotypical. People choose to drive or take public transport as a result of all manner of factors such as to differences in their job types, need for travel during the day, office/non-office work, access to public transport, access to parking, etc, etc. Without more facts I would have say I still disagree on this.

LikeLike