On Saturday I did a guest lecture to the Master of Applied Finance course at Victoria University. Martien Lubberink, who runs the course, invited me along to talk to the students about the Reserve Bank’s monetary policy this year (as it happens, most years for the best part of two decades I used to do a lecture to this same course articulating and championing the monetary policy framework and the Bank’s conduct of policy).

There wasn’t a great deal in the lecture that hasn’t already been covered in one or (many) more posts over the course of the year, but if anyone is interested here are the slides I used

Activity over substance VUW presentation 12 Dec 2020

and this is the story I was trying to tell

Notes for VUW MAF lecture on 2020 mon pol 12 Dec 2020

For the most part, I tried to look at what the Bank has, and hasn’t, done on their own terms. I didn’t, for example, spend lots of time on whether negative OCRs would “work”, but rather took as given the Bank’s repeatedly stated view that they would. I didn’t challenge the “least regrets” approach they have claimed, since the second half of last year, to be guiding them, but looked at how they had done relative to that worthy aspiration. I took for granted their embrace of the notion that in downturns when both inflation forecasts undershoot and unemployment forecasts overshoot aggressive monetary action is warranted. And against the backdrop of all that sort of thing I suggested that the year was best characterised as one of lots of activity, and rhetoric, and not a great deal of monetary policy substance.

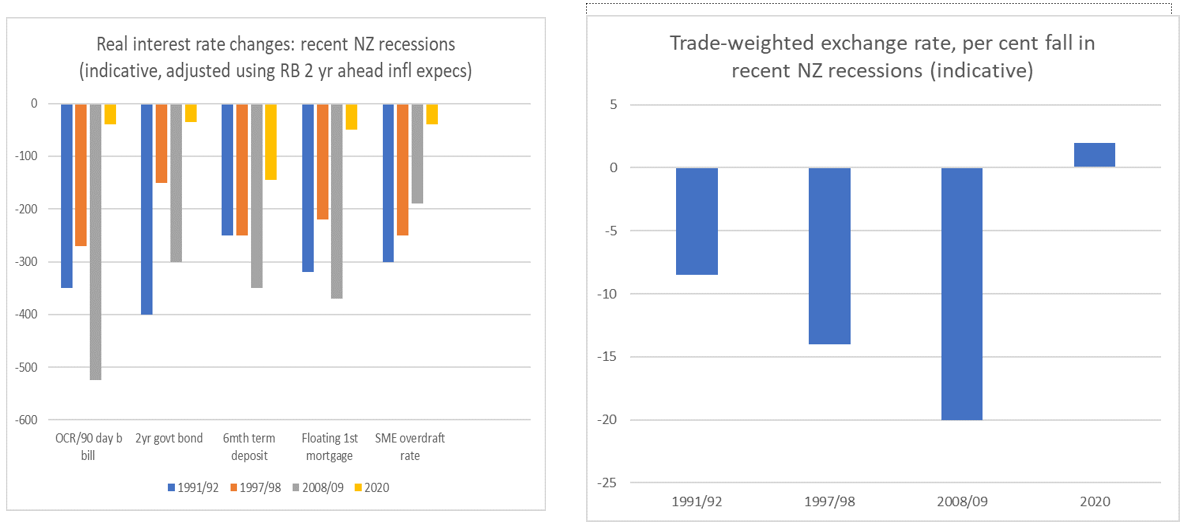

For example, I included these two indicative charts comparing (real) interest rate and (nominal) exchange rates this year and in each of the three previous recessions since inflation targeting was adopted.

Whatever the impact of the LSAP and the funding for lending programme etc, the bottom line remains that key financial market prices just haven’t moved very much (and that is another area where I take as given – but also agree with the Bank – that to the extent those programmes work they do so largely by altering interest and exchange rates).

I ended the lecture with some thoughts on how we should evaluate the Bank’s monetary policy performance this year. From my notes

How should we evaluate the Bank’s performance?

We always have to be careful, when evaluating government agencies, not to hold them to unreasonable standards. In this talk I’ve tried to ensure that I use either information that was available to them when they made decisions, their own rhetoric and arguments, or common international central banking practices and standards. We can’t blame the RB, for example, for not pre-emptively easing a year ago in anticipation of a pandemic no one – no central banker anyway – could reasonably know about.

But we, and should, criticise them for:

- The failure to recognise and respond to the emerging risks early (monetary policy works with a lag, risks around being near the lower bound were well known),

- The failure, having decided that the negative OCR was a preferred option, to have ensured the bulk of the system was operationally ready (almost inexcusable, and has meant we have had monetary conditions tighter than otherwise for most of the year,

- The failure to operate as if “least regrets” was actually guiding policy – the evidence for this not being my independent analysis, but their own numbers,

- Falling back on exuberant spin regarding the impact of the LSAP, when realistically the effective impact is likely to have been small,

- Opening the way to the “$100bn money printing” rhetoric by adopting LSAP rather than a mod-point on the yield curve target (as the RBA initially did, and even the LSAP the RBA is now doing is much smaller relative to the size of the economy),

- Allowing the (second-best) sensible FFL instrument to also be framed as some dangerous money printing exercise,

- Lack of serious transparency – whether the utter refusal to publish background analysis/research behind the mon policy choices/instruments, even in extremely unsettled times and when the rest of govt was being proactively transparent, or the continued invisibility and silence of the non-executive members of the MPC, and

- The lack of effective communications and framing. There have been few speeches all year, hardly any published research, nothing from the non-exec MPC members. Instead, they’ve largely left the framing of issues to critics – notably the ones who think the Bank has done too much and is to blame either for house price inflation and some looming general inflation. There has been nothing authoritative from the Bank, and they seem constantly to have been running to catch up.

It has been a poor performance, that reflects poorly on all those involved: the Governor, his senior staff, the invisible non-exec MPC members, the Board (paid to hold management to account) and the Minister with responsibility for management and the Board.

Of course, it is fair to ask how much difference a better monetary policy – substance and presentation – might have made. By now, perhaps not a lot substantively – the mon pol lags are longer – but into next year it would have helped lay the foundations for a strong recovery, a lift in inflation, and a rapid return to full employment (we can’t afford the 10 years it took after 2007). And, agree with them or not, the RB would stand higher in informed opinion, and if we value the idea of an operationally independent central bank, that would have to have been a good thing. It would truly have been a least regrets strategy.

At the end of the lecture, we had some time for questions. Perhaps the best question was the one I could not give a compelling answer to: why – given their projections, given their avowed “least regrets” approach – has the Bank and MPC not been willing to do more?

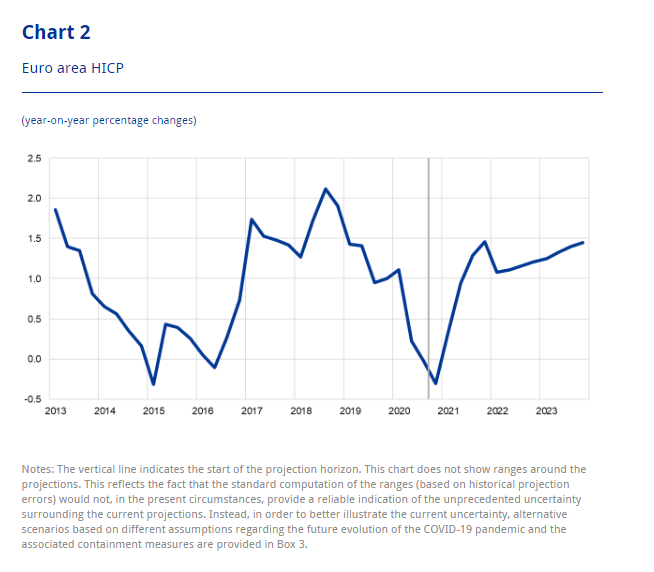

I had noted that there were similar issues with central banks in a number of other countries, and indeed that it was striking how relatively little monetary policy had done in this downturn and period of greatly-heightened uncertainty. You can see it in, for example, the published projections of the Reserve Bank of Australia, the ECB, and probably others too – where for several years to come not only is inflation expected to be below target, but unemployment is above general estimates of the respective NAIRUs. As our Governor notes, that is a combination that points in the direction of a lot of monetary policy support.

(As just one example of what is going on elsewhere, the ECB released its latest projections late last week.

Three years out inflation is still barely back to 1.5 per cent, compared with a target of just under 2 per cent. In these same projections, the unemployment rate rises further from here.)

Central banks could do more to boost the recovery in activity and employment. The quiescent inflation numbers – their own projections – tell us that. In fact, those projections (and market and survey expectations) are best seen as a constraint limiting how much central banks can do; a constraint that when inflation projections are below target should be thought of as a non-binding constraint (especially when central banks around the world have had an upward bias to their inflation forecasts for the last decade).

So why don’t they do more? I don’t know. They don’t say – especially not our Reserve Bank which talks one set of rhetoric (often quite good rhetoric) and acts inconsistently with that rhetoric. Perhaps there is something in the story that active-government left-liberal Governor doesn’t want to use monetary policy because he wants to put pressure on the government to run bigger deficits and further increase public spending. I hope that isn’t a part of the story – it would be profoundly inconsistent with our democratic institutions of government for a non-elected official (and his lackeys on the MPC) to refuse to do their job simply to try to advance their personal political preferences in other areas. Perhaps they don’t believe the rhetoric (they themselves use) and doubt that monetary policy can do much more good in stabilising the economy. Perhaps there is some secure-public-employee indifference to the scandal of prolonged and unnecessarily high unemployment (which never affects senior central bankers, and probably rarely their children): it did, after all, take 10 long years after 2007 to get unemployment in New Zealand back down again. Perhaps there is some embarrassment that with all those years of advance notice they didn’t get their act together and ensure that banks were operationally ready for negative OCRs? Perhaps, globally, there is some discomfort that with all those years advance notice – most having got to the lower bound in the last recession – nothing (repeat nothing) has been done anywhere to make the lower bound less binding, and enable the sorts of deeply negative interest rates that (for example) former IMF chief economist Ken Rogoff has called for.

Sure, it is easy for people to talk about all the fiscal stimulus that has been provided instead of monetary policy. But those published central bank forecasts – here or in other countries – capture all those effects. It is the job of monetary policy to estimate all the other effects and then, if the inflation outlook is below target and the unemployment outlook is above NAIRU-type estimates, to do more, to do what it takes. with monetary policy. That is what we have discretionary monetary policy for. (There are, of course, hard cases where the inflation and unemployment strands aren’t aligned, but as our own Governor has repeatedly pointed out this year, this isn’t one of those times.)

So, I really don’t know the answer to the student’s question. But I should (as should anyone who follows central banks closely), because they should be telling us. Instead, we’ve had a year of few speeches, no visibility (still) for the non-executive MPC members, little or no published research, a refusal to release background documents and analysis, and little or no attempt to articulate and defend a robust framework. 10 days or so ago, for example, the Governor gave a speech to an Australian audience on New Zealand monetary policy this year. As far it went, and by Orr’s standards, it wasn’t a bad speech but it addressed none of these questions. That isn’t good enough, and reflects poorly on everyone involved – the Governor, the MPC, the Board supposed to hold them to account, and the Minister of Finance with overall responsibility for the Bank, for monetary policy, and for economic performance more broadly.

There has been a lot of rhetoric, a lot of busy-work, but not a lot of monetary policy doing what it is there for, and not much transparency and accountability either.

Michael

I feel you are being unfair to RBNZ and disregarding the uncertainties they face.

In 2020, RBNZ shifted focus from CPI+Employment to Fiscal Facilitation

Allowing government to pump billions into the economy to provide fiscal offset for the effect of the pandemic.

The effectiveness of RBNZ/Government is illustrated by the latest GDP data which shows an almost complete recovery in activity.

Could RBNZ have done more? Its not clear they could or should have. In particular, their ability to undertake Fiscal Facilitation is based on inflation remaining quiescent. Given the inflationary forces looming, prudence on RBNZ’s part seems very sensible.

Tim

LikeLike

Thanks for those comments Tim. To respond briefly, the Bank’s mandate did not change this year at all, and nothing that they did really made much difference on the “fiscal facilitation” side, except perhaps for that couple of weeks in late March when global bond markets were a bit topsy turvy,

On the economic/inflation/unemployment outlook, I built my presentation around their Nov MPS numbers, and the Governor in his recent Aus reaffirmed his view that risks at to the downside. Clearly they could have done more – at v least taking the OCR to zero,

As for the “inflationary forces looming, all I can really say is “maybe, and didn’t we hear the same story in the US/Uk/Europe 10 years ago?” and “so far, in NZ in particular neither surveys nor market measures of inflation expectations expect even as much inflation as was being expected this time last year.

I think one mount an argument along your lines, but the RB (given what else they have said, repeatedly) can’t.

LikeLike

Tim, the only inflationary forces on the horizon is the incompetence of the Ports of Auckland in clearing their backlog. The logjam of products and also the additional costs of trucking containers from alternative ports will certainly give imported consumer products an inflationary boost. This is somewhat offset by the abundance of high quality fruit produce that are not exported due to the same logjam because now they are short of empty containers to export product.

When China, Vietnam and India’s mega factories have excess inventory and excess production capacity inflation is not going anyway fast. Global forces beyond our borders determine whether we have inflation or not. There is nothing much the RBNZ can do when global consumer product prices are falling.

LikeLike

Chaps

I recommend you read a paper from the MAN Group. Inflation Regime Roadmap June 2020. It was awarded the “Best Investment Paper 2020” award. Im sure you can Google it

Even if you are skeptical about inflation rising, there are three points to note. The potential is there. Investors are VERY concerned about the potential. Were it to happen central bank freedom would be materially circumscribed.

Inflation and deflation are both possibilities and as such, investors and the RBNZ have to take account of the risks.

Tim

LikeLike

Thanks Tim. Interesting piece from a few months ago, and inflation breakevens have moved up a bit since then. Personally I remain a bit sceptical , esp about NZ and Aus where govt debt is still quite modest, but only time will tell. Remember, however, that my critique of the RB was based largely on their model and their outlook, which still emphasise the downside and deflationary risks.

LikeLike

Tim, the inflation risk in the US is due to the 25% import tariff imposed on Chinese products in Donald Trumps trade war with China. With US market access being restricted you can expect NZ inflation to keep falling as Chinese products get dumped in other markets. The NZ dollar has also climbed to now $0.72 against the USD which means even cheaper imported products.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Utopia, you are standing in it!.

LikeLike