I’ve written a couple of posts over the months drawing on work by Waikato economics professor John Gibson. Back in April there was this post, and then last month I wrote about an empirical piece Gibson had done using US county-level data suggesting that government-imposed restrictions in response to Covid may have made little consistent contribution to reducing death rates (in turn consistent with evidence suggesting that much of the decline in social contact, and economic activity, was happening anyway, in advance of government restrictions).

Fascinating as I found that paper, I was never entirely convinced how far the point would generalise, It seemed implausible, for example, that government restrictions and “lockdowns” would never make much difference – even if, in practice, the particular ones used in US counties might, on average, not have. After all, at the extreme, if a population (wrongly) regarded the threat from a particular pandemic as fairly mild, and yet some megalomaniacal government nonetheless banned all cross-border movement and ordered that no one was to leave their home for six weeks it is quite likely that – gross over-reaction as the government’s reaction might be – fewer lives would be lost from the virus under extreme lockdown than with no government restrictions. Then again, if the public was right and the government was wrong, such a lockdown would not save any material number of virus deaths, but would come at an enormous cost, whether in economic terms or personal and civil liberty.

That earlier paper also used only US data, and although there is an enormous richness in US data – since restrictions were imposed at state and county level – there is the entire rest of the world, even just the advanced world, to consider. As it happens, Professor Gibson has now done another short paper looking at (much of) the OECD countries – most of the advanced world. Here is his abstract.

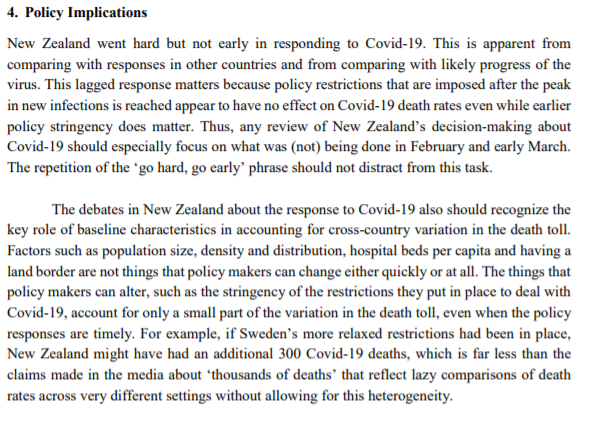

A popular narrative that New Zealand’s policy response to Coronavirus was ‘go hard, go early’ is misleading. While restrictions were the most stringent in the world during the Level 4 lockdown in March and April, these were imposed after the likely peak in new infections I use the time path of Covid-19 deaths for each OECD country to estimate inflection points. Allowing for the typical lag from infection to death, new infections peaked before the most stringent policy responses were applied in many countries, including New Zealand. The cross-country evidence shows that restrictions imposed after the inflection point in infections is reached are ineffective in reducing total deaths. Even restrictions imposed earlier have just a modest effect; if Sweden’s more relaxed restrictions had been used, an extra 310 Covid-19 deaths are predicted for New Zealand – far fewer than the thousands of deaths

predicted for New Zealand by some mathematical models.

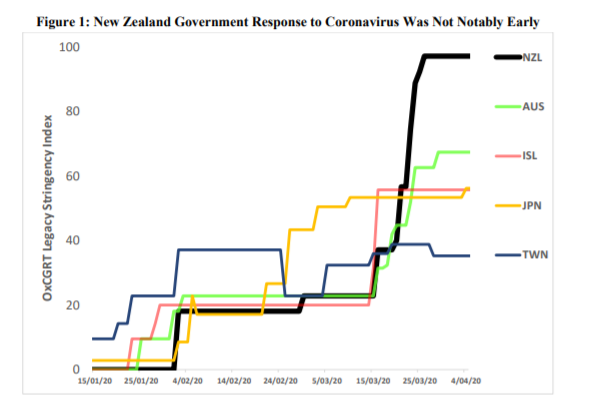

Professor Gibson does not seem at all taken with the Prime Minister’s “go hard, go early” catchphrase. He argues that the New Zealand government went hard, but actually rather late. He begins the paper with this chart, comparing restrictions in New Zealand and several other advanced island countries (ISL being Iceland).

And observes

Up until mid-March the New Zealand response generally lagged the other countries in Figure 1. Moreover, the initial response, from 3 February, required foreign nationals arriving from China to self-isolate for 14 days. In late February, this extended to travelers coming from Iran. Subsequent genomic sequencing of confirmed cases in New Zealand from 26 February until May 22 shows representation from nearly all the diversity in the global virus population, and cases causing ongoing local transmission were mostly from North America (Geoghagen et al. 2020). Thus, aside from self-isolation being poorly policed, restricting travelers from certain countries (for example, China, Iran) is ineffective at keeping the virus out, unless all countries in the world simultaneously impose the same restrictions. Without such coordination, the virus can spread to third countries, from whence it can enter New Zealand. It is like bolting one door on a stable with many exterior doors, with horses free to roam around inside so that a smart horse (aka ‘a tricky virus’) can escape through any of the other doors.

And goes on to note that

The evidence in Figure 1 is open to at least two criticisms. First, different comparator countries may allow alternative interpretations. Secondly, comparing with responses of other countries may not be the right metric. Sebhatu et al (2020) find a lot of mimicry; almost 80 percent of OECD countries adopted the same Covid-19 responses in a two-week period in midMarch: closing schools, closing workplaces, cancelling public events and restricting internal mobility. These homogeneous responses contrast with heterogeneity across countries in how widely Covid-19 had spread, in population density and age structure, and in healthcare system

preparedness. One interpretation of this contrast is that some governments panicked and followed the lead of others, rather than setting fit-for-purpose Covid-19 responses that reflected their local circumstances. So another approach to study policy timing is to compare policy responses with the spread of the virus in each country.

Gibson adopts an approach of working back from data on Covid deaths – imprecise as that it, it is generally regarded as better than direct estimates of case numbers, which are hugely affected by just how much testing has been done – to estimate when there must have been a turning point in infection numbers to be consistent with the observed deaths data. That involves using an estimate, informed by experience, of the lag from infections to deaths (he mentions a couple of papers estimating lags of three to four weeks). Gibson produces results for 34 OECD countries, although unfortunately (for New Zealand comparisons) not for Australia.

The results in Table 1 show that the inferred inflection date in infections ranges from February 23 to 4 June, and for the median OECD country occurred on 23 March. For New Zealand, the approach in Figure 2 suggests new infections peaked on March 16, over a week before the strictest restrictions began on 26 March. Even if a shorter lag from infections to deaths is assumed, the peak in new infections in New Zealand still will have occurred before the Level 4 lockdown began. New Zealand is amongst 17 countries whose peak policy stringency occurred after the likely turning point in infections. So based on comparing policy

timing with likely progress of the virus, the ‘go early’ claim seems untrue.

He argues that it matters

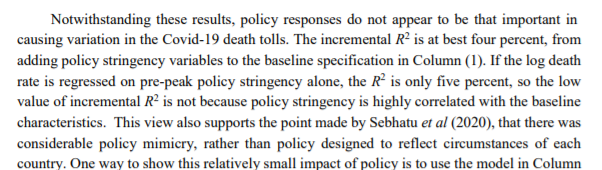

It matters that policy restrictions are applied too late. Over two-thirds of variation in Covid-19 death rates (as of August 18) across these 34 OECD countries is due to baseline characteristics: deaths are higher in more populous countries, with higher density, higher shares of elderly, immigrants and urbanites, and fewer hospital beds per capita and having land borders (Table 2). If the country-specific mean of the OxCGRT policy stringency index is included it provides no additional predictive power. However, if the time-series of policy stringency is split at the inflection point in infections for each country (based on Table 1), prepeak policy stringency is negatively associated with Covid-19 death rates while post-peak policy stringency has no statistically significant effect on death rates. A similar pattern is apparent if the (likely) dates of peak new infections are controlled for, or if the maximums of the stringency index are used rather than the means. Thus, it seems to matter more to ‘go early’ than to ‘go hard’.

Gibson goes on to deal with concerns about endogeneity, re-running tests looking at policy responses relative to those of other nearby countries. Doing that tends to confirm the thrust of the earlier results.

there is a precisely estimated negative elasticity of death rates with respect to the policy stringency that was in place prior to the peak of new infections and an insignificant effect of policy stringency after the inflection point in infections has occurred.

But even then the effects appear to be quite small

And what of New Zealand?

or, in the slightly less-loaded framing from the abstract

if Sweden’s more relaxed restrictions had been used, an extra 310 Covid-19 deaths are predicted for New Zealand – far fewer than the thousands of deaths predicted for New Zealand by some mathematical models.

Of course, all those 310 would have been people, with grieving families, but on this model, we would have had a rate of deaths per million still in the lower half of OECD countries (rates akin to many eastern European countries, and Norway) not to those of (most of) northern Europe, including Sweden.

Having read and reflected on the paper, and engaged on a couple of points with Professor Gibson, I thought there were still several points worth making in response:

- unlike his earlier paper, this paper makes no claims about what was known, or not known, by New Zealand and other countries’ governments in mid-late March. Even if the true number of new infections had started to decline even prior to the New Zealand “lockdown” policymakers could not have used this methodology at the time (since the deaths – the foundation of the timing estimate – had not yet happened). Reviews with the benefit of hindsight are not without their considerable uses – most real-world reviews are of that sort – but it is important to be clear that that is what this paper is. Politicians, of course, use their own take on hindsight to reinforce their preferred narratives,

- the results may depend quite a bit on the correct specification of the model, and in particular on whether the other variables included (country population, population density, elderly share of the population, foreign-born share of the population, per cent living in urban area, available hospital beds per capita, and the presence/absence of a land border) have a robust foundation. The one I was particularly sceptical about was country population, as I could not see a good reason for it to affect Covid death rates. I asked Gibson about it and he re-ran the model without that variable and in summary “the basic pattern of results in terms of the policy variables stays the same, and particularly the contrast between pre-peak and post-peak stringency”. As it happens, this variant produces a lower estimate of New Zealand deaths with Swedish-level restrictions than the models reported in the paper itself. (Gibson, however, continues to think a population variable has a sensible structural interpretation.)

If we take Gibson’s results at face value they seem pretty appealing (and, in many respects, not that surprising, since we know – from papers since released – that officials in mid-late March were not recommending a lockdown of anything like the stringency of what the government actually imposed).

That said, it isn’t clear to me what the nature (and quantification) of any tradeoffs around economic costs and loss of liberties might be. There is a reasonable argument – and it is the stance I take myself – that the extreme restrictions on economic activities and liberties should be counted as a very large cost, justifiable (if ever) only in the face of the most severe and near-certain threat. What sort of society are we when we tolerate a government banning a swim in the sea, banning funerals, banning any public celebration of Easter, banning utterly safe economic activity (a sole practitioner going to his or her place of business)? But perhaps there is a counter-argument if maintaining the sort of moderate death rate Gibson envisages also required that we kept Swedish-type restrictions in place right through the last six months? It is possible – but needs for work, more modelling – that the total economic costs might have been similar or even higher. But then should one put a higher price on the most extreme episodes not just weight all losses equally? Perhaps there is a clearer-cut argument there in respect of restrictions on liberties than on the narrower GDP effects, perhaps especially when we recognise that different people value different things, different freedoms, different obligations in different ways. And that arbitrariness and unpredictability of use of extreme controls should itself be represented as carrying, and imposing, a heavy cost.

My position all through has been that the government over-reacted in adopting the full extent of its so-called “Level 4” restrictions. But the issues in my mind then was a difference between a New Zealand “level 4” and the somewhat less severe approach adopted in Australian states. With the benefit of hindsight, a paper like that of Professor Gibson poses more questions – and the sort of the questions that need to be posed, since the virus hasn’t gone away and (for example) we see Israel being forcibly locked down again. I hope his paper gets some scrutiny from, and engagement with, some of the more thoughtful of the champions of the New Zealand government’s approach. Perhaps he is quite wrong and his conclusions just aren’t sound, but they look like results that should warrant serious engagement, perhaps even a question to the Minister of Health, the one who the other day was trying to pretend the government does not (implicitly or explicitly) put a dollar value on human life in making its spending/regulatory decisions.

You know the rules were silly when even the Minister of Health is caught, not once, but twice, breaking them….

LikeLiked by 2 people

Many rules appear to have been designed with an objective of disciplining the society (or scaring it into obedience) rather than pragmatism. But then, politicians giving those rules human face are faced with a Hobson’s choice as no politician is going to state publicly that some, potentially severe consequences are acceptable. Particularly in view of the concerted panic-mongering in the media and equally scary public pronouncements from a number of “experts”. The political cost would be just too high. And so we persist with an illusion that “eradication” is possible or indeed achievable…

LikeLike

Yuou may want to check the copied abstract – it does not read well.

LikeLike

Thanks. Fixed now.

LikeLike

Thx!

LikeLike

The definition of “Early” is reasonably important to this analysis.

New Zealand went early in terms when the first cases started to occur in New Zealand.

Our relative isolation meant that our first cases arrived well after infections were occurring at quite concerning rates elsewhere, particularly in Italy and UK from memory.

I’m very much a layman in this type of analysis but on the face of it Sweden has a higher fatality rate and worse economic (unemployment) outcomes than we have had.

The restrictions on funerals in Levels 3 and 4 is questioned, but what about the experience of the church members who overlooked the numbers allowed at a meeting for a funeral event with the outcome of significant virus spread which arguably resulted in the period of current restrictions being extended.

The only area (apart from 3rd world economies where the data is probably not reliable) that I see has done better than NZ, and that is better from both health and economic perspectives, is Taiwan.

Your comments on this layman’s perspective would be welcomed.

LikeLike

The fatality rate as shown on publicly available web pages could be misleading as there’s no standard way of recording fatalities – each country does it in their own way. Far more enlightening, at least in my own uneducated view is the rate of hospitalization, fairly low for virtually all countries.

Similarly, it is very difficult, if at all possible to make a meaningful comparison between various countries in economic terms. Can we rally compare two countries as different as Taiwan and NZ? Or Sweden and NZ?

LikeLike

Beware of reading too much into the HLFS unemployment figures. At present, the Ministry of Social Development estimates that 198.9k are on Jobseeker support (7.1% of the labour force) with a further 18.6k on COVID-19 Income Relief Payments (0.7% of the labour force) and a whopping 375.4k are on the Wage Subsidy (13.5% of the labour force). So, at present we have 592.9k people either on the unemployment benefit or receiving a wage subsidy, that’s a remarkable 21.4% of the labour force or more-than one in five of the labour force. The Wage subsidy has cost the taxpayer $13.9bn, or about 4.5% of GDP. Then there’s the fact that something like 16% – or about one in six – mortgages have been either deferred or moved to interest-only. Also, key commodities – dairy and meat – prices have fallen and the ToT has only really held up because of the fall in global oil prices and then we are about to have a summer without tourists.

Call back in 6-months and tell me things are fine…

LikeLiked by 4 people

Agree with Belarus re the economics – far too early to tell. But note that Gibson’s paper isn’t holding out Sweden as a model, just using their restrictions as one illustrative example.

NZ’s experience is an odd mix. Looking back, we were astonishingly lucky not to have had a case at all from China, given the number of people travelling to and fro before China and then we put restrictions on. In Gibson’s analysis, “early” is just about when we acted hard relative to the estimated peak in infections, altho note that on his model even acting early does not have that large an effect.

On your final main para, it really is too early to tell on the economic impact side, altho in terms of death rates Singapore and S Korea are also (per capita) v similar to NZ. For our econ outcomes, every economists recognises that even Thursday’s GDP number will be only a first draft estimate and there are likely to be big revisions to come.

LikeLike

I saw an interesting analysis of explanatory variables for Sweden’s higher death rate compared with other Nordic countries. One possible explanation is that countries like Denmark and Norway had quite severe flu seasons in years preceding Covid, while Sweden did not. What this meant was that Sweden had a lot of people left living who would otherwise have died in a severe flu season. Using a bush fire analogy, they had more fuel load than comparators so had a more severe fire.

This explained between 20 and 50% of the disparity in deaths that may not have been accounted for in simple statistical analysis.

https://www.newsroom.co.nz/swedens-disaster-in-disguise – link to the abstract in the article

LikeLiked by 1 person

Have to tell you that it was around the motor camps in January. Lots of oversea’s tourist and some no at all healthy.

LikeLike

But if it really was Covid it should have spread more broadly and eventually have shown up in hospitalisations etc.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Utopia, you are standing in it!.

LikeLike

New Zealand’s population density is 19 per square km, Sweden’s is 23, and almost exactly double our population. 5,846 people have died there due to COVID-19. It truly beggars belief that we would only have approx 300 deaths, given that the Swedish people are probably more disciplined and the health system is likely much better.

The only things I could think of that may explain the difference is us having better control at the border, and that if we didn’t go early, we went earlier than Sweden. Is that accounted for in the model?

LikeLike

Fair points, altho recall that Gibson’s paper isn’t using Sweden as a model (restrictions, or outcomes) but estimating off the experience of 35 OECD countries and simply using the Swedish level of restrictions as an illustrative example.

LikeLike

I still point to our higher UV levels that reduces the speed of the viral multiplication factor. Sweden has an average UV factor most of the year around UV factor 1 or 2. In NZ our UV factor is consistently above 11 or 12. US bio weapons studies indicate strongly that UV does effect viral rate of multiplication and spread.

LikeLike

This is going off on a somewhat different tangent, but Michael what did you make of Brian Fallow’s article in which he basically says that applying cost-benefit analysis to a Government’s COVID response is inappropriate, indeed I think he says ‘repugnant’?

For example, he says “If loss of income were the only reason to mourn someone’s passing, their funeral would be poorly attended. It is a mistake to treat the economy as a whole as if it were the Pharmac budget writ large. The benefits and opportunity costs are not all of a piece….Of course lockdowns are bad for business. So is having the border closed to all but returning expatriates. Perhaps the Swiss found World War II bad for business.But were they not fortunate to be an island of peace and neutrality amidst the carnage?”.

Etc.

Thoughts?

LikeLike

I thought it was really strange, and even a bit obtuse. But one does have to careful about the framing and perspective. I would give my life to save my children, but I would not expect the state reasonably to spend that sort of amount to save my child, given all else it could do with the same amount of money. I would give my life for my child, but at my age I would be reluctant to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to save my own life.

The final line seemed particularly odd: I suspect WW2 was quite good for Swiss business, but there is – or should be – some moral stain on them for not having paid price and joined in the effort to topple Hitler and resist his invasions. Some causes are worth paying a v high price for – us joining WW2 might be an example.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Remember as well that loss of income isn’t soley tied to the economic pain. It has direct influence on quality and length of life.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are so right Paul the costs are very high our very humanity.

We are not suppose to cower in fear, be locked up and socially distance.

Oh and in response to Jon below: In Melbourne the testing numbers dropped off when the central banking govt ” got all Nazi on them”. The PCR test used is “experimental use” as it cannot be used diagnose infection/disease. And yet that is what the govts are using it for.If you were a non corrupt microbiologist you’d be disgusted.

https://notpublicaddress.wordpress.com/2020/08/27/stop-testing-and-youll-stop-covid/

LikeLike

Putting a healthy population in home detention and imposing bizarre measures and non science based rules had a huge psychological negative impact that has not yet been looked at .

The MOH not reporting increased suicide stats is how a tyrant would deal with social impacts .

The “lockdown” was not science based.

https://notpublicaddress.wordpress.com/2020/08/20/petition-to-the-supreme-court-of-nz/

LikeLike

Home detention is a significant overstatement of what Level 4 was, let alone what the conditions were for Level 3 and are for Level 2.

There is science around the impact of lockdowns, with Melbourne being an example close to home. Check out the infection trend before and after lockdown was implemented (I don’t agree with lot’s of the detail on Victoria lockdown, but it’s impact on reducing rate of infection is very obvious).

The MOH doesn’t report suicides, they are determined by the coroner. It takes time to hold an inquest and that’s why the statistics are slow being available.

Hopefully that helps you understand some of the issues you are concerned about.

LikeLike

I understand you are an economist and you could not understand the science or legal.

Never mind.

There is no science this is all political.

Its called a psyop.

There is no isolated new virus and no new disease” covid” no evidence of it at all .

The RT PCR test can’t diagnose disease/infection …its meaningless.

Here’s the origin of the covid Hoax( but you’d need a science background )

https://notpublicaddress.wordpress.com/2020/08/08/how-to-create-your-own-novel-virususing-computer-software/

PS

The MOH do collect suicide figures data but stopped when the numbers got to high.

LikeLike

My wife and I have sufficient background to be able to understand the Lancet paper referenced on the above link that clearly comments on treatments for Covid 19.

If the Lancet reports on the success or otherwise of treatments then I’m fine to take that evidence that the virus exists.

But then I also believe the science that on a personal basis 5G is less harmful than 4G so maybe I’ve been wifi washed.

I don’t expect we will agree so let’s agree to disagree and leave this discussion at this point.

LikeLike

You do not have the understanding( medical and science) needed and this ignorance and blind belief in authority ( after terrifying people ) is a relied upon condition in a psyop.

PS I have communicated with the lancet and they have not known or forwarded info of any scientist that has isolating a new virus( Sars CoV2). Coughs ,pneumonia and stress induced hypoxia are not new symptoms or a new disease. the set of symptoms use to be called the ” flu”.Now the flu is a bio-terrorist weapon called “covid”.

LikeLike