I’m still less than entirely well, so posts here will stay less frequent and less regular than usual for a while yet. That means things like last week’s OCR decision pass by with little comment (my only one will be, in what conceivable world five years ago would a severe global recession, the drying up of a major local export industry, falling inflation and inflation expectations here and abroad, and recognised downside risks be met with precisely no monetary policy action?).

But I see that the Governor has been out giving interviews – the ones I noticed were with Stuff and the Herald – and some of his comments conveniently tie in with what I was wanting to write about the results of an OIA request to the Bank that belatedly turned up in my inbox on Monday, on the elusive question of what the Bank is (and isn’t) doing about negative interest rates.

You’ll recall that in the second half of last year the Governor was dead-keen on the option of negative interest rates. It wasn’t just a passing comment, but a very substantial interview. Who knows, perhaps the rest of the MPC didn’t agree with him, but he was supposed to be the spokesman for the Committee as a whole. We don’t know what the other MPC members – the ones who don’t, at least on paper, work for Orr – think, and they seem to exist in a state of purdah, refusing ever to make speeches or give interviews.

As recently as the Governor’s speech on 10 March this year – when he and his colleagues were still attempting to play down the economic challenges of Covid – the Governor outlined his preferred tools. He promised then that

We will provide our full analysis of each of these tools against the principles we hold in coming weeks – so that people can fully understand our thinking and, of course, provide input.

None of that analysis has ever been published. The list of tools was clearly organised in order of the Governor’s then preference: forward guidance (just a variant on what they always do) was first, and then

Negative OCR

Reduction of the OCR to the effective lower bound (the point at which further OCR cuts become ineffective), which may be below zero. The Reserve Bank could consider changes to the cash system to mitigate cash hoarding if lower deposit rates led to significant hoarding.

Not only did a negative OCR appear to be in play, but that really encouraging second sentence suggested they might actually have considered doing something – they are technically easy things to do – to allow the OCR to have been cut even further below the negative levels which at present could lead to large-scale shifts into physical cash.

That was then. A few days later the MPC decreed that in fact that OCR would not be changed, up or down, from 0.25 per cent for a year, claiming the matter was really ou of their hands as “banks weren’t ready”.

It was, and remains, a very strange argument given that:

- several other advanced countries had had negative official rates for some years,

- a large share of global government bonds had been trading with negative yields for some years,

- in New Zealand the first negative yields (on indexed government bonds) were recorded last year, at about the time of that interview the Governor gave,

- the Reserve Bank had shown revived interest in these issues for a couple of years, and

- that eight years previously an internal working group (set up by the then Governor, chaired by me) recommended that relevant departments should ensure that (a) the Bank’s own operating systems, and (b) commercial banks’ systems could cope with negative interest rates. Those recommendations were accepted at the time.

In other words, if the Bank’s claims now are really true, commercial banks seem to have been astonishingly (or conveniently, since banks hate negative interest rates) remiss and (more importantly, since it is a powerful public agency) the Reserve Bank ((Governor, Deputy Governor, MPC – and the Board paid to hold them to account) had to have been asleep at the wheel. Given a decade’s advance notice of the risk that market-clearing interest rates would go negative here too, they would appear to have done nothing. That would be egregious neglect – for which people at the bottom, the involuntarily unemployed, would pay the price.

The Bank, of course, likes to claim that it is highly transparent – they have been at it again this week – even as they remain as obstructive as possible on anything they don’t want to be transparent about. The negative interest rates situation has been one of those topics. For example, they’ve staunchly refused to release any of the background or advisory papers the MPC received running up to 16 March, on this or any aspect of monetary policy (as a reminder, the government itself has been pro-actively open, even with papers that may embarrass some or other bits of government).

I had one go with an Official Information Act request that got nowhere. But it is a bit harder to stonewall Parliament, and thanks to the efforts of the National Party members of the Epidemic Response Committee we got some useful material out of the Bank. The Bank didn’t want to draw any attention to this material, but it was there on Parliament’s website, and I wrote about it here.

The Bank told MPs that they’d started to take things seriously at the end of last year

More broadly, bank supervisors raised the issue of preparedness for negative interest rates at banking sector workshops in December 2019.

In late January 2020, the Reserve Bank’s Head of Supervision sent a letter to banks’ chief executives formally requesting they report on the status of their systems and capability.

By late January, of course, Wuhan was already locked-down.

The Bank told the MPs that there had been a range of issues identified, and while they hoped banks were doing something about them, it didn’t want to put any pressure on banks because they were busy people, and had other priorities (which, even if so, would not have been the case had the Bank done its job several years earlier).

None of this was very satisfactory. They never explained – or were pressured to – their own past failures, nor why these alleged readiness issues had not been obstacles in other advanced countries (the euro-area, Sweden, Switzerland, Denmark, Japan), the prevalence of negative wholesale rates abroad.

A few weeks later again, the Governor told the Finance and Expenditure Committee (hearing on the May MPS) that a letter had gone out to banks just the previous week apparently urging or requiring them to have systems ready by the end of the year. I then lodged a further OIA request

Section 105 is the dreadful provision in the Reserve Bank Act which allows the Bank to avoid any scrutiny of its bank regulatory activities under the OIA. When the response to this OIA arrived this week, they had invoked it to allow themselves (so they claimed) to refuse to release anything in response to item (a) in my request. This is a provision that, to the extent it had any merit, is designed to protect highly sensitive individual institution material in the middle of a banking crisis (in fact, of course, anything commercially confidential is already protected, and reasonably so, under the OIA). The readiness of banks’ systems and document for negative interest rates is clearly not primarily – barely at all – a prudential issue, but primarily a monetary policy one. But that doesn’t stop the Bank – the ones that always claim to be so transparent.

However, the Bank did belatedly release what I was after under the second and third strands of my request. The full response is here.

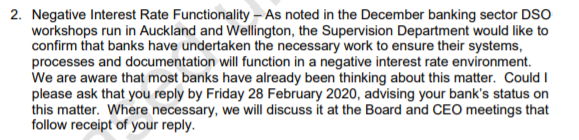

The 29 January letter is on page 4 of the response. It is a catch-all letter from the head of bank supervision drawing attention to various issues large and small that the Bank wanted to deal with this year (among the latter, the Bank’s Maori strategy). Here is the relevant text on negative interest rates

Okay I guess, but with little or no sense of urgency.

There is a three page table summarising the responses from each individual bank (although remarkably one banks appears to have never even responded), complete with this interesting somewhat defensive observation from the Reserve Bank which I had not initially noticed.

“We acknowledge the banks’ responses to our letter of 29 January were a preliminary assessment of their readiness to implement negative interest rates.”

The table is interesting. Of the 19 banks, a fair number are described as ready, but it is fair to note that a number of issues are also highlighted, in some cases in enough detail to be genuinely somewhat enlightening. This is all, however, material that could have been pro-actively published in March, and which the Governor – and those commenting on his draft speech – must have been aware of on 10 March.

Perhaps it is also worth noting that these are individual bank responses, without the benefit of any RB pushing and prodding to better understand how binding perceived constraints might be, what workarounds might be possible, let alone with any sign of the Bank itself having learned from the experience of their counterparts in countries that had operated with negative interest rates for years.

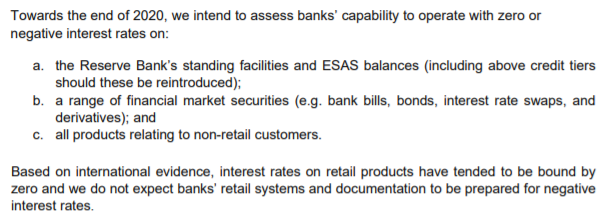

Anyway, all this was then somewhat overtaken by the new letter, dated 7 May. It is from the Deputy Governor, Geoff Bascand to the chief executives of banks. This must have represented the Bank’s (or MPC’s) thinking at the time of the May MPS, although there is no hint – of course – of it in the minutes of the MPC meeting. The letter set out a deadline of 1 December 2020 for banks to ensure that they were capable (with status reports due yesterday). That wasn’t news, but what was was how limited the Bank’s requirement’s (and ambitions) now are, in the middle of the deepest economic slump in a long time.

In other words, they’ve just given up on negative retail interest rates. It isn’t true that in other countries there have been no negative retail interest rates, even with policy rates slightly negative (here is story from just last year of negative retail mortgage rates in Denmark, and recall that lending rates are usually higher than funding rates). And, of course, look back up to the quote from the Governor’s March speech – as recently as then they were open to the possibility of taking the steps that might allow the OCR usefully to be cut more deeply than other countries have done.

Coming back to today, what also interested me was that the Governor continues to muddy the waters on this. In his interview with Stuff there are quite a few comments about negative interest rates.

The Reserve Bank is still warning retail banks to get ready for a negative official cash rate. Rolling this out has been said to be difficult because banks systems weren’t ready and some contracts with depositors didn’t envisage a negative interest rate – effectively a charge on depositors.

Orr said most banks were in a good position to deal with negative rates.

“Only a handful of banks” were having difficulty with negative rates.

Orr appeared to downplay the extent to which a negative rate would impact all areas of a bank.

“What we’re doing at the moment is double checking with all of the banks, so they’re not trying to get absolutely everything capable of a negative [rate] because we don’t need absolutely everything.

“We’re saying it’s a small proportion; it’s the wholesale side of the business,” Orr said.

Ordinary depositors likely wouldn’t notice a difference because rates would still be positive for depositors.

“Internationally the experience has been that banks have been highly reluctant to go below zero for a deposit.

“In fact, retail banks’ reluctance to pass on negative rates to consumers are likely to act as a brake on the Reserve Bank’s appetite to push rates lower.

“There is a limit to how far negative wholesale rates can go in large part because the retail rates end up holding up,” he said.

Read that and you wouldn’t know that the Reserve Bank had told banks they didn’t need to bother about negative retail rates – in fact, you’d get the impression it was banks that could never envisage offering such products, even though they are on offer in other countries.

But you’d also get the impression that the Governor was more concerned for banks than for the New Zealand economy and the people who become unemployed because monetary policy isn’t doing its job. If his Committee had aggressively cut the OCR another 100 basis points, to (say) the -0.75 per cent often envisaged as an effective floor until steps are taken to disincentivise cash hoarding, not only would the banks that had prepared themselves got on with things, and presumably been advantaged, but the others would have snapped to pretty quickly and got workarounds in place. (That, after all, must have been what happened in other countries, and is more like the way the rest of government operated – when a wage subsidy was decided on, MSD wasn’t given nine months to do systems testing etc; when a small business loan scheme was decided on IRD didn’t months to prepare).

And there is no sign at all of the Reserve Bank taking seriously steps to remove the obstacles to a more deeply negative OCR, even though those obstacles are all of the public sector’s making.

Perhaps none of this would matter very much if you believed the spin about what good monetary policy was doing overall, including through the LSAP programme. But it is just spin. Benchmark term deposit rates have been falling a bit more recently, but that means they are now 85-90 basis points lower than they were at the start of the year. But, of course, expectations of future inflation have also fallen quite a lot. There is a range of possible measures, but a reasonable pick might be a fall of about 60 basis points. In other words, real retail deposit rates are down perhaps 30 basis points in the midst of a savage slump for which there is no obvious end. The exchange rate is usually a key buffer for New Zealand, a significant part of how the monetary transmission mechanism works. It bounces around a bit, but at present the TWI is sitting almost bang-on the average level for the second half of last year. For all the handwaving and big numbers (around the LSAP) monetary policy just isn’t doing its job, and the Bank seems to have little interest in it doing so.

On Monday I went to hear a speech the Governor gave. In the course of that address he seemed to defend monetary policy doing not much on the grounds that “the expenditure had to be immediate”. And at one level, for the March/June quarters no one is really going to dispute that – monetary policy doesn’t work that fast, and there was a need (or a good case) for lots of immediate income support, especially for people rendered unable to work by government fiat. But that was then. Wage subsidies have replaced lost income (a large chunk of it) for a few months – at the expense of an increased involuntary burden on taxpayers to come – but meanwhile we are still in a deep recession, still have our borders largely closed, and the state of the world economy appears to be worsening. Monetary policy should have been positioned – and should now be positioned, it isn’t too late – to support domestic demand and activity through the (probably protracted) recovery phase – much lower interest rates, and a much lower exchange rate. As it is, monetary policy – designed as the primary countercylical tool – has done almost nothing and the Bank seems quite unbothered about that.

It isn’t good enough. We need better from the Governor and his Committee (including, for example, to actually hear the excuses of the rest of the Committee members), and we need the Bank’s Board – hopeless cause I guess – to be doing its job holding the Committee to account. But, of course, the person who could make this all happen is the Minister of Finance, who has long-established directive powers, but seems to prefer to do nothing, content to spend taxpayers’ money while doing nothing to remove the roadblock to getting market price signals better aligned with responding aggressively to our economic plight. Don’t rock the boat, don’t be bold, don’t worry too much about the actual unemployed seems to be the government’s approach. Robertson and his boss like to invoke memories of the first Labour government, but it is hard to imagine those big figures in Labour’s history being happy to sit by and see a central bank wave its arms and do nothing to get us quickly back to full employment.

Michael

Best wishes for a quick and full recovery of your health.

I struggle to understand your enthusiasm for negative central bank rates. I guess there could be an effect on the NZ$, but across the board I’d have thought that there were better tools.

If the RB prints money and buys US Treasuries it would (all else equal) improve local liquidity and lower the NZ$.

For the creation of credit, they could ramp up initiatives to support bank lending, such as improving the terms under which they would provide term funding to the banks for the banks to on-lend.

Another plus of not using negative rates is (in my opinion) likely to be on savings rates. A radical move like negative rates is hardly going to generate confidence that will drive households to consume rather than to save.

So, all in all, it seems to me that a lower NZ$, more corporate credit, and more consumption could all be better progressed via something other than negative central bank rates.

Tim

LikeLike

Thanks Tim

If there were another way of materially lowering the TWI I’d happily sign on. I tend to be sceptical that buying USD assets will make much difference, and it seems from his comments that the Governor and staff probably share my view on that count. In conjunction with a negative OCR on the other hand it might be helpful.

On savings, for the next few years at least less desired savings is probably a good thing. There isn’t much investment demand (or, relatedly, demand for new credit.

In the end it comes down to fiscal policy, monetary policy, or little or nothing. Fiscal policy has done a lot in the short term, but the real political limits of that will cut in soon. Monetary policy has done a little. At present, the risk is that we will see unemployment continuing to climb – Tsy seem too optimistic on current policy re a Sept quarter peaks – and eventually falling very very slowly (it took 10 years after 2007 to get the unemployment rate back to something normal).

LikeLike

If the intent is to ensure that the banks lend out their deposits then there must be a cost to the banks. Negative interest rates means that they get to charge to hold deposits rather than to lend it out to create an income. Negative interest rates will just create less lending liquidity in the market.

No negative interest rates. All common financial sense screams “No” even though being a borrower I would hugely benefit. With property prices already starting its upwards momentum in terms of price, you can only gorge on some much before it gets into gluttony and one of the 7 deadly sins.

LikeLike

Michael

I suspect that the election campaign over the next 3 months will put a “sell” on the NZ$.

Providing a third option to monetary and fiscal policy.

The Green’s “tax and give away” is a handy start. Its interesting that they have chosen to fire what seems likely to be their most differentiating shots first.

I get the feeling that the Greens and ACT are staking out the left and right fringes. I wonder how the other three will seek to capture the votes of the middle?

Tim

LikeLike

You may well be right re the election and the NZD, altho if so it won’t necessarily be a helpful fall if, eg, it reflects worries about the Greens’ agenda and the potential adverse effects of that on productive potential.

LikeLike

I do agree with Tim and GGS.

My belief is that a negative OCR would be put NZ monetary stability at real risk!

Rosecevans

LikeLike