Over the last few days I was reading John Gunther’s Inside Latin America. For those who haven’t come across Gunther before he was an American journalist (and novelist) who really made his name with a series of these Inside books – the first was Inside Europe in 1936 (he’d been a correspondent in numerous European capitals) – that are a mix of history, politics, key personalities and issues in the countries he visited (there is even, late in his career, a New Zealand/Australia one). He appeared to have access to almost anyone and everyone. They are period pieces, and that is their value.

Inside Latin America was published in August 1941, drawing on five months Gunther had spent visiting almost all the Latin American and Caribbean republics. It was well into World War Two, but at a time when the United States itself was still, at best, in a support role, and when it still seemed plausible to many – notably in Latin America – that Germany might yet win the war. From the US side, one of the big concerns was German infiltration and influence throughout much of Latin America, and the perceived risk that if Germany had won the war in Europe many of the Latin American countries might adopt Nazi-sympathetic regimes, perhaps even in time posing some direct military threat to the US. Certainly the Germans took Latin America very seriously indeed, spending heavily on propaganda and influence operations (actually, as I read it the parallels to the activities of the CCP/PRC kept springing to mind). There is a lot in the book on the extent of German influence, and the countervailing steps most of the local governments were by then taking.

And there was a single reference to New Zealand, or more strictly to a New Zealander. Perhaps some of you had heard of Lowell Yerex who was born in Wellington but moved to the US and was at this time the driving force, and main owner, of Transportes Aéreos Centroamericanos, at the time the largest freight-carrying airline in the world. I hadn’t. He sounds like a fascinating character (there are apparently two books about him, one of which I now have on order, or if you google “erik benson, aviator of fortune, essays in economic and business history” you can download the PDF of a journal article that will give you much of the flavour).

But, of course, this is an economics blog. And although Gunther is no economist, he does write quite a lot about trade and production – both of which, at the time, were quite badly disrupted by the war. And he was almost boundlessly optimistic about the economic potential of Latin America. As, I suppose, many western authors had been since 1492 or thereabouts.

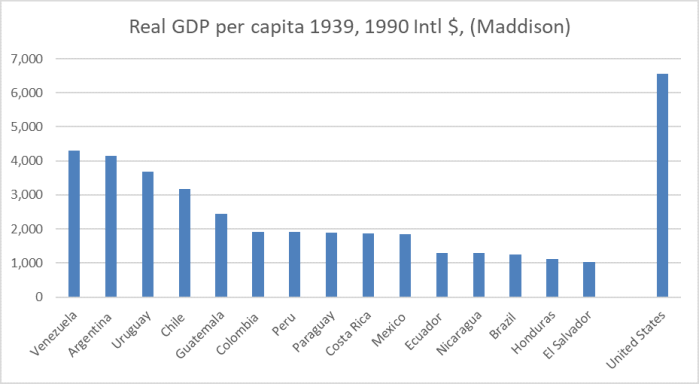

I pulled up the standard reference work for such comparisons, Angus Maddison’s collection of estimates of real GDP per capita, expressed in purchasing power parity terms. For 1939 – a year whose economic data was not materially affected by the war – Maddison reports estimates for 15 continential Latin American countries.

Across all 15 countries, average real GDP per capita was 33.7 per cent of that of the United States. The average of the top four countries was 58.4 per cent of the per capita GDP of the United States. Venezuela (with oil), Argentina, and Uruguay at this time all had GDP per capitas ahead of both Italy (from whence a large chunk of Argentines had come) and Spain (even looking back prior to the civil war, which only ended in early 1939). Take a combination of no serious wars in Latin America itself and abundant natural resources and I guess one could see some reason for Gunther’s optimism.

That was then. But how have things turned out since? In summary, not that well. Of course, all the Latin American countries are materially better off than they were in 1939, but for comparative purpose that doesn’t tell us much.

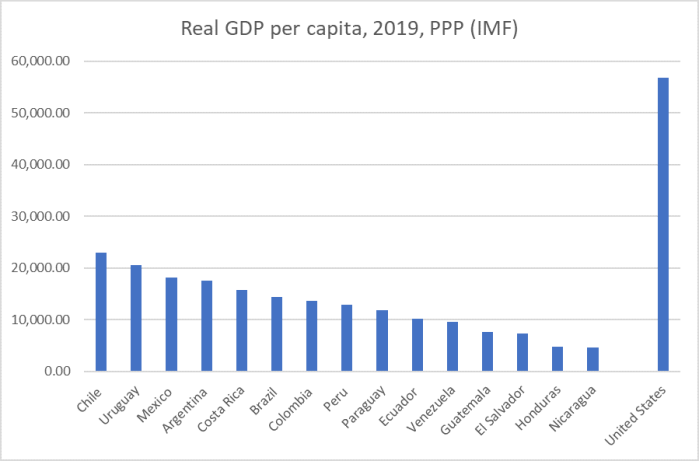

These days, there is per capita GDP data for a wider range of countries in Latin America (more independent countries as well). But for this post, I simply looked at the same group of countries as Maddison reported data for for 1939, using the IMF’s WEO database. Here is the same chart for 2019 (2018 for Venezuela).

There have been some changes in rankings among the Latin American countries: Chile and (the very large) Mexico and Brazil have done relatively well while, of course, Venezuela has been a self-destructed disaster. But simply glancing at the graph is enough to tell you that the Latin American countries as a group have fallen further behind to the US over those 80 years. Averaging across this group of countries, their GDP per capita was by 2019 only 22.5 per cent of that of the US, and even the average of the top-4 countries is now only 34.9 per cent of that of the US. There are now three OECD countries in Latin America – Chile, Mexico, and Colombia – and the best of them, Chile, has real GDP per capita barely 40 per cent of that of the US.

And it isn’t as if the past 80 years have been glory days for the United States. I mentioned earlier that in 1939 the top-performing Latin American economies generated GDP per capita higher than those in Italy and Spain. But from Maddison’s data there was a “top 10” group of western and northern European countries: in 1939 the average of Latin American economies had GDP per capita about 41 per cent of that of the top European grouping, and the top 4 Latin American countries averaged about 71 per cent of top European countries grouping. Respectable enough I suppose.

But over the last 80 years, with all sort of interruptions (the war notably) Europe has really done quite well relative to the United States – and, even more so, relative to Latin America.

Italy might be in a mess now, with little or no per capita GDP growth this century, but both Italy and Spain have real GDP per capita more than 50 per cent higher than the best of the Latin Americans (Chile). And in comparison with those top-10 European countries (not including either Italy or Spain), the average for the Latin American countries has fallen to only 26 per cent of European GDP in 2019 (41 per cent for the group of four best-performing Latin American countries).

One finds a similar sort of Latin American decline if one compares those economies with Canada or Australia (Canada’s GDP in 1939 was only about 10 per cent higher than that of Venezuela).

But, of course – and you probably knew this was coming – if the Latin Americans don’t want to feel so bad about their economic performance, there is always New Zealand.

Across that whole group of 15 Latin American countries, since 1939 there has been a very slight lift (they were 34.3 per cent of New Zealand, now 35.8 per cent). But the top-4 grouping (and recall that the composition of that group has changed, favouring Latin America in the comparison) they’ve actually fallen relative to us – from 59.3 per cent to 55.5 per cent).

Our performance has been quite bad enough, but at least our starting point (1939) was second-highest GDP in the world. The Latin American performance – recall all that potential – has been just dreadful.

Preparing this post prompted me to dig out an old post I wrote about Uruguay/New Zealand comparisons – both small countries with temperate climates, lots pastoral agriculture, nice beaches (and Uruguay has been one of the more politically stable Latin American countries).

In that post I included a chart showing how much faster productivity growth had been in Uruguay than in New Zealand since 1990. That improvement has continued in the last few years. On Conference Board estimates Uruguay has the highest real GDP per hour worked of any of the Latin American countries, and now, on their estimates, is about about 76 per cent of that in New Zealand.

Unfortunately for them, “better-performing than New Zealand” is about all that they can really claim. Real GDP per hour worked in Uruguay has improved only very slightly relative to the US in the last twenty years, and Chile – with the second-highest productivity levels in Latin American – is now further behind the US than they were in 1970 when Salvador Allende – an up-and-coming man to watch when Gunther wrote – took office.

Fascinating. I remember Gunther’s books well, I used them for high school essays, long before the internet. I visited Uruguay ten years ago, along with Argentina and Chile. I was struck by Uruguay’s relative optimism and vibrancy. New Zealand for its part now seems to be heading off on a Peronist track with a renewed focus on the role of labour unions and growing state involvement in the economy through wage and income subsidies. Perhaps we have found our own “Evita”?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Bit confused with your last graph. Which is NZ & which is Latam. Doesn’t seem to add up to the figures quoted.

LikeLike

They are ratios. The first set is the 15 Latam countries relative to NZ, and the second the top 4 Latam countries relative to NZ.

LikeLike

I am reading “Why Nations Fail”, Daron Acemoglu and wondered if you have come across it, it delves into South American economic failure.

LikeLike

(guility he says) it has been sitting on my pile for years waiting to be read. Sadly – or perhaps not (better to have the literature than not) – there is a vast literature on Latam econ and political failure, some more convincing than others.

Of course, some stories of NZ’s relative decline are also more convincing than others, but – being one small country – there is much less literature. My recent contribution (in a book coming out next month) is here

Click to access an-underperforming-economy-the-insufficiently-recognised-implications-of-distance-draft-chapter.pdf

LikeLike

Thanks, will look for it.

I would concur, although I disagree with NZ problem solving ability, I think it is high relative to some other countries but would note that it was only at a post graduate level that I was taught about the difference between complicated and complex problem solving. We are trained to solve complicated problems at university and then run into complex ones.

LikeLike

At University, we learn the lofty standards of accounting, business rules, process mapping and case study solutions. In real life it is about profit and money in the bank to put food on the table, to have regular family holidays, to drive a car, to have at least a 50 inch TV, a new smartphone and a few luxuries as and when you want to buy.

In real life it is about compromise and that creates complexity. Our solutions in real life are about percentages, keeping as many stakeholder people happy, knowing there will be sacrifices. At University we find the best solutions to case studies without needing to worry about people.

LikeLike

Michael, your chapter is a very interesting read. But one paragraph caught my eye, even as you passed on to other matters:

Immigration policy was also influenced quite strongly by the large outflow of New Zealanders…, which prompted the idea that policy should “at least replace those who are leaving”. Although no serious analyst would have been likely to have applied this logic to an individual town or region where the opportunities were scant – standard policy prescriptions would then typically focus more on flexibility and encouraging people to move to where the new opportunities were – it has been a recurrent line in the discussion of New Zealand immigration policy.

No serious analyst might apply that logic to a declining town, but the politicians in charge do so regularly. Among many similar examples in Italy, Japan and elsewhere, the Mayor of Cammarata (Sicily) is offering free houses to anyone who will commit to renovating them within three years. Sensible policy advice would be for the Mayor to wish departing residents well as they move away to better opportunities, and be ready to turn out the lights as the last one leaves. (Newfoundland ran such a programme from the 1950s to the 1970s, subsidising the closing of unviable villages.) The reason he does not do that is that he is responsible to the people who remain in Cammarata, who want a pleasant and viable community to remain even though the economic reason for its existence has long gone.

Cammarata’s policy for attracting more residents is pretty much NZ’s business immigration policy. We know that NZ’s policy is not achieving much, and it is unlikely that Cammarata’s will either. (Potential buyers are reportedly balking at the cost of renovating homes that should really be demolished, and at the tens of thousands expected in fees and permits for the renovation work.) But one should not expect that the policies that serious analysts might recommend will appeal to those faced with responsibility for a formerly successful region which is being left behind by economic and technological change(*). Their incentives must form an important part of the explanation for the policies that they adopt, and those policies will not include allowing population decline.

(*) NZ is not as badly off as Cammarata, of course. Cammarata probably has no remaining reason to exist at all, while NZ still has economic viability as a resource-based economy. But neither can maintain its former position in the world, and neither should try to retain its previous population numbers – but both of them will.

LikeLiked by 2 people

The America’s Cup race next year will draw in hundreds of thousands of people. House prices and rents are rising as the sailors, supporters, fans and support staff flock in. The question is now why are many sailors still stuck without an entry Visa when they are prepared to self quarantine?

Don’t forget our population rose to 5 million even under the severest border lockdown NZ has ever seen. Unfortunately we need people to get stuff done. Expect more people and not less. We keep planning for less and that’s why NZ are lousy planners.

LikeLike

Our institutions are no longer fit for purpose. We can no longer assume the telos of academia and consequently journalism and the public service? Things have been happening outside the norm.

LikeLiked by 2 people

IT Information Technology it trumpeted as an “industry” with tremendous potential in and for NZ. Today the news media informs us the the government funded a covid-19 program of $83 million to supply modems to every school child in NZ aimed particularly at schools in lower-socio-economic areas.The Education Department supplied the main ISP’s with the school rolls. The ISP’s would match their client databases with the school rolls and supply and deliver the modems. Each modem cost $500. The program has not been a success. Probably a fiasco. The principal of Auckland Grammar received 200 modems that no one needs. They are now stored in a cupboard. A number highly paid professional parents have received letters offering the grant even though they already have internet connection with all the requisite hardware. Many schools have not received an allocation. Some children who have accepted the offering do not have a connection to the internet of a laptop. But now they do have a $500 modem

LikeLiked by 2 people

“”To err is human, but to really foul things up you need a computer.””

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am a registered Mentor as a Chartered Accountant. The newbies that I mentor usually complain they have not been trained at work whenever they make a mistake or that they just followed what the previous person had done. My reply is that , they have not paid attention at their Universities because everything they need to do their jobs have been learned and taught over 3 years at the University. Do not expect the company to teach what the newbies already should know. That is why employees get paid. Not sure or don’t know, ask.

I as the mentor cannot know what you don’t know.

LikeLike

Interesting and thought provoking commentary as usual Michael.

For my part, I am deeply skeptical of using data on productivity from some of the Southern European countries, notably Italy. Italy has enjoyed colossal implicit transfers from the Northern European countries through the Target 2 mechanism in the ECB and I don’t think we’ve yet to see the final act of this play, which will most likely result in Italy defaulting and departing the Euro-Zone and Germany becoming saddled with loans via the ECB which will be worth cents in the dollar. Italy could well emerge as a total basket case.

Meanwhile back here in New Zealand, we increasingly face the prospect of a Red-Green coalition government post-September. It doesn’t strike me that many New Zealanders have really taken onboard what this might mean for the country. We have already moved a long way towards an autarkic and socialist economy with all the implications this has for productivity growth. Post-election it is almost certain that this government will look to raise taxes on higher income earners and I would expect them to also broaden and deepen the capital gains tax. For my part, I am already working on Plan B, which will result in me no longer funding the equivalent of 2-3 State employees with my taxes.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Your taxes also fund hospitals, the police, the military, the roads, the electricity grid, social welfare etc etc. Note that social welfare and Treaty of Waitangi payments are the price of peace and security. The alternative is barb wire, sand bagged compounds, armed bodyguards and armoured vehicles.

LikeLike

My problem is that the Treaty of Waitangi is a British Crown document with Maori. The sins of the British Crown and the liabilities should go through the Governor General and sent to the Queen of England to seek redress. This issue really is nothing at all to do with the New Zealand Taxpayer who is now expected to pay for the sins of great grandfathers.

LikeLiked by 1 person