I wasn’t quite sure how the economic recovery was going when this morning I walked past five outlets offering coffee and food, within the current “Level 3” rules, and counted three customers between them. Time will tell.

I’ve accumulated a few monetary bits and pieces over recent days that haven’t naturally fitted into any other post, so thought I’d use today’s post to cover them, although without any specific connecting thread. But it is, after all, the Reserve Bank’s Monetary Policy Statement tomorrow.

First, if the determination of the Reserve Bank to avoid any substantive transparency weren’t so serious – monetary policy being, after all, the key cyclical stabilisation tool and New Zealand now being in a savage recession – it can sometimes be so absurd as to be almost funny. In early April I lodged an OIA request for material the Bank had generated or received in March around issues relating to negative interest rates. March, you’ll recall, was when the MPC suddenly told us negative interest rates were off the agenda for the next year, and management told us it was because “the banks weren’t ready”. This has always been a fishy excuse, particularly as it never seems to have been advanced by central banks anywhere else in the world.

I finally got their response last Friday, in the last hour of the last day it was due. They’d decided to interpret “generated” as meaning (only) “already published”, and so refused to release anything, other than the slightly-enlightening but not very specific paper they’d given to the Epidemic Response Committee, and which Parliament had published, during April. Quite where you find a dictionary that equates “generated” with “published” is anyone’s guess, but for the Bank’s purposes it doesn’t really matter – they either close down the request or see it kicked to the Ombudsman and the latter is unlikely to deal with it inside a year. And yet they like to boast about how transparent they are. Oh, and they also claimed that finding and collating what they’d received on these narrow specific points – in March, just a few prior to my request – would take so much time and work, and they were so busy, they just could not answer, not even with an extension of the deadline. But they’re a transparent central bank……they claim.

(It was a bit like the Bloomberg article I saw this morning in which the Reserve Bank is reported as saying that after a year of operation they had been just about to make external MPC members available to the media, when unfortunately the coronavirus intervened. Perhaps they really were just about to open up, but it was reminiscent of the “the dog at my homework” or “the cheque’s in the mail” sorts of line that few take very seriously.)

On a more analytical note, I saw a nice piece from Willem Buiter – former Bank of England MPC member, former Citibank chief economist. former monetary academic – on “The Problem with MMT” in the current context. I know some readers have an interest in so-called Modern Monetary Theory, and I regularly refer people to a post I did on it a few years ago when the chief academic champion visited New Zealand.

In the current context. some are advocating that governments – in countries with their own currencies – can spend just as much as they like, financed – directly or indirectly – by central banks.

As a technical matter, of course they can. As Buiter notes

To be sure, some parts of MMT make sense. The theory views the treasury (or finance ministry) and the central bank as components of a single unit called the state. The treasury is the beneficial owner of the central bank (or, put another way, the central bank is the treasury’s liquidity window)…

MMT holds, correctly, that because the state can print currency or create commercial bank deposits with the central bank, it can issue base money at will.

And in current circumstances, doing so is unlikely to be troublingly inflationary – and, if anything, given the falls in inflation expectations were are observing, a bit more support for inflation near target would not be unhelpful. Banks are currently voluntarily holding $29 billion of settlement cash, up from the $7 billion of so they willingly hold in normal circumstances.

But even in the current climate, the demand for base money at (or very near) zero interest is not without limit. More importantly, things can’t sensibly be assumed to remain like this forever. As and when interest rates need to start rising, either the Reserve Bank will have to pay much more interest on those settlement cash deposits or do some other market operations (eg sell government bonds back to the market) that have the same effect.

This is the relevance of my comment yesterday, which happens to overlap with Buiter’s above, that what happens between the government and the Reserve Bank is really of second-order importance at most – inter-divisional transfers. I’ve had people ask about the potential for the Reserve Bank to simply write-off all the government bonds it is buying. It could probably do so, but it would make no substantive difference to anything. The branch of government we call “the Reserve Bank” would have huge negative equity, but as a technical matter central bank capital really doesn’t matter that much at all (I once worked for a central bank where not only was the capital deeply negative but the accounting/computer systems were so bad we couldn’t even produce a proper balance sheet….and yet we got inflation properly under control.) What matters is how much the government (as a whole) is borrowing from the private sector as a whole – and what changes that is fiscal deficits/surpluses – and whether the government (as a whole, including the Reserve Bank) is willing to do what it takes to keep inflation around target.

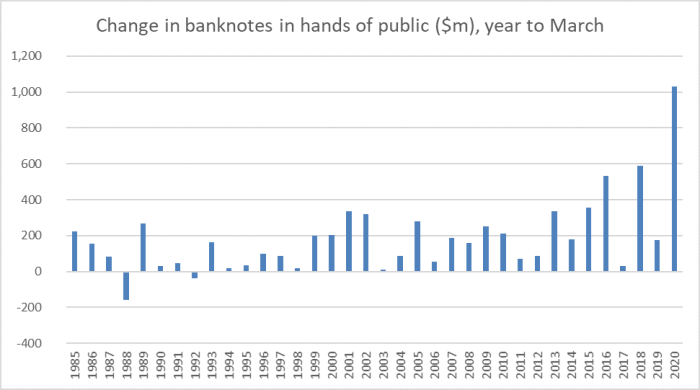

As it happens, we already have an indication of how much very long-term non-repriceable zero interest lending people are willing to do each year to the New Zealand government (as a whole).

And although bank notes don’t have a maturity date they are – at present – redeemable at par, anytime the buyer chooses to sell them back. It took the fear of a pandemic and lockdown to get net new demand up to $1 billion a year – and in all probability next year’s number will be a lot lower again.

Somewhat related to this, there is a great enthusiasm at present – particularly it seems among bank economists – for the Reserve Bank’s large scale bond purchase programme, widely expected to be substantially increased tomorrow. It isn’t clear to me quite why market economists are so keen on this activity which – in a New Zealand context in particular, where there is little long-term fixed interest rate private borrowing – seems largely irrelevant from a macroeconomic perspective. Expect the Reserve Bank tomorrow to wave around fancy estimates suggesting some equivalence to really large OCR cuts, but judge for yourself: is the exchange rate down much, are retail or wholesale real interest rates down much, is voluntary credit growth up much, were banks constrained by inadequate stocks of settlement cash? If not, you can safely conclude that whatever value the bond purchase programme might have in helping secondary market liquidity, it isn’t do much to stabilise or improve the economy. If asset purchase programmes are still doing something useful for bond market liquidity – and there is some public interest in supporting this – actually cutting the OCR and doing bond purchases simply don’t need to be alternatives (as the Bank and many private economists keep doing).

One of the incidential curiosities of the bond purchase programme is that at times like this you hear a great deal of talk about how it is a wonderful time to borrow and the government can lock in very cheap long-term funding. And yet what do really large scale central bank bond purchase programmes do? They transform the liabilities of the Crown from quite long-dated to increasingly quite short-dated, exposing the Crown (us as taxpayers) to really substantial interest rate risk. Perhaps at the end of all this the Reserve Bank will have $50 billion of government bonds, with a representative range of maturities. On the other side of its balance sheet, it will have a lot of very short-dated (repricing) liabilities – all that settlement cash (see above). Whether the Bank eventually sells the bonds back into the market – which hasn’t happened a lot in other countries – or holds them to maturity, the interest rate risk doesn’t go away. It isn’t obvious what public interest is being served by skewing the Crown’s (net) debt so short term. Perhaps interest rates will never rise again……but that won’t be the view many people will be taking,

And then, of course, there is the small matter of how much interest rates have fallen at all.

We know that floating first mortgage interest rates came down by 75 basis points back in March when the Reserve Bank belatedly cut the OCR. That isn’t much consolation as surveyed inflation expectations – medium-term measures – are down by about 70 basis points.

Some people don’t like me constantly focusing on floating rates (which I do for several reasons, including (a) a long time series, (b) the more-direct link to the OCR, and (c) the fact that even if most new borrowers initially take a fixed rate, much of the stock of debt ends up on floating rate terms.

But I try to be at least a little open-minded, and the Reserve Bank does publish data on fixed rate offerings. I had a look at their table of new special residential mortgage rates for various initial fixed terms, and updated it to now from the tables on interest.co.nz. Unfortunately, since the end of last year the typical offerings – fixed rate specials – has only fallen by about 25 basis points. At best, the one year rate is down by about 35 basis points. And did I mention that inflation expectations are down about 70 basis points.

What about term deposit rates? Again, I mainly focus on the six month rate because there is a very long-term time series. But the Reserve Bank does now publish data for a wider range of maturities. Again, I updated the numbers to today. Very short-term rates (1-3 months) seem to have come down perhaps 50 basis points since the end of last year, but for any longer terms the fall is only around 30 basis points. Perhaps I’ve mentioned that inflation expectations have fallen about 70 basis points?

We don’t have anything like that transparency around business lending rates but I suspect we are pretty safe in concluding that those real interest rates won’t have fallen either.

And all this amid the biggest economic slump on record…..and with all that (alleged) support from the bond purchase programme.

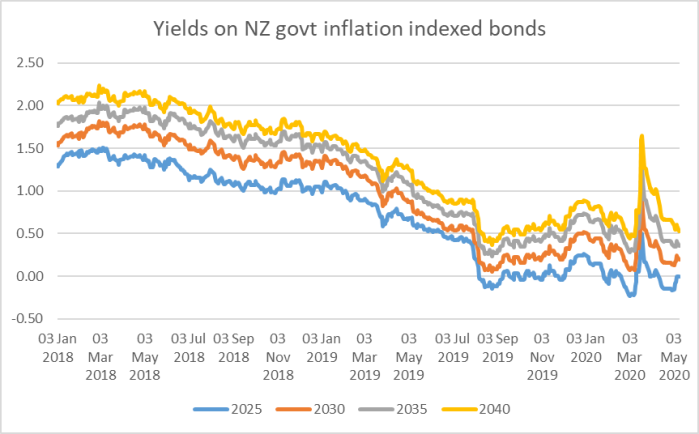

As it happens, of course, we can get a direct read on real interest rates from the inflation-indexed government bond market. There are the yields for the four bonds on issue, with maturity dates from 2025 (now about five years) to 2040.

You can see the huge spike in yields in March, at the time of the global asset liquidation. But once one looks through that what one notices is that current real interest rates are not as low now as they got in August/September last year and barely different that they were in December. The Reserve Bank’s bond-buying programme is not at present buying inflation-indexed bonds, but those yields will have been affected anyway.

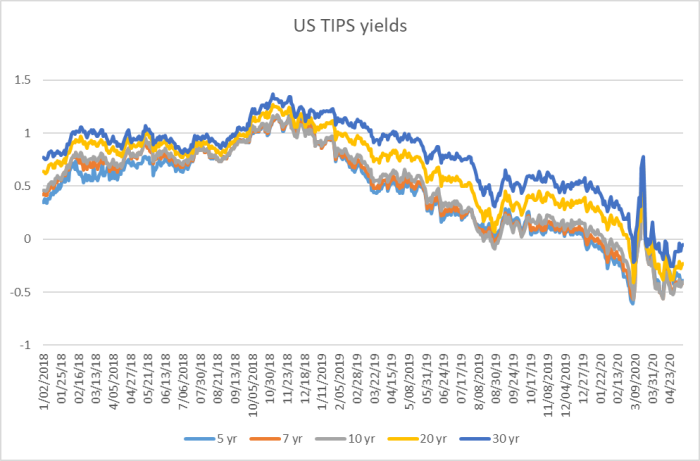

In isolation perhaps that wouldn’t be so interesting – after all, perhaps the market was just banking on a really quick rebound in economic activity. But this chart is much the same one but for the United States.

In the US, even the longest-term indexed bond yield is a lot lower now (50-60 basis points on a 30 year bond) than it was in the second half of last year. And recall that the US government debt is a lot higher – share of GDP – than ours is, or is likely to become.

What explains the difference? Well, one factor – probably not the only one – is that the US Federal Reserve has cut short-term interest rates this year a lot more – 150 basis points – than most other countries, including New Zealand. Lower short-term rates often influence long-term rates. When our Reserve Bank refuses to cut the OCR more – in fact not at all in real terms – perhaps it isn’t that surprising our real longer-term yields haven’t come down.

Incidentally, there was some excitement last year when, for a time, New Zealand nominal government bond yields fell below those in the United States. But do note that end-point levels on those two charts: New Zealand real 20 year bond rates are just over 50 basis points, while comparable US rates – as a much more heavily indebted borrower – are about -25 basis points. We can even compare implied market rates for the second 10 years of a 20 year indexed bond: in the US -10 basis points, and in New Zealand around +90 basis points.

So for those who are keen on the really low interest rate narrative and the suggestion that governments should be borrowing-up large, just recall (a) interest rates are low for a reason, (b) New Zealand long-term interest rates remain well over those in the United States (itself a relatively high interest rate advanced country soveriegn borrower, and (c) for what its worth, our long-term productivity performance has been lousy (productivity is relevant here because a country with really rapid productivity growth on a sustained basis might tend to support sustainably higher real yields).

For now, we all await the Monetary Policy Statement tomorrow. If there was jusr one question I’d like to see journalists ask the Governor (or MPs if FEC is having a hearing) is “quite what is there to lose from doing what it takes to drive the OCR deeply negative, as former IMF chief economist Ken Rogoff advocates?” Is the recession not deep enough, unemployment not high enough, or are perhaps upside inflation risks troubling you? We deserve to know. On the face of it, the MPC simply isn’t doing its job.

In the meantime, if anyone is interested in tuning in I’m appeared at the Epidemic Response Committee at about 11 tomorrow, to talk about economic policy responses to the impact of the coronavirus – both what’s been done to date and what might need doing (the Committee proceedings are livestreamed and are also on Parliament TV). Appearing straight after me is Ian Harrison of Tailrisk Economics whose work I’ve linked to here on various occasions. From talking to Ian, his session should be particularly stimulating.

Is there a link for tuning into Epidemic Response Committee, or can we find it from Parliament TV?

LikeLike

Freeview 31, Sky 86, Vodafone 86.

or

https://www.parliament.nz/en/pb/sc/scl/epidemic-response/news-archive/watch-public-meetings-of-the-epidemic-response-committee/

LikeLike

Brilliant. Thanks for that Michael … I’ll tune in.

LikeLike

Hi Michael. I don’t think you can read the real yields on NZ inflation-indexed bonds too literally (especially so forward real interest rates). There are are illiquid (even more so now, and they’re weren’t liquid before) and the liquidity premium will inflate the real yield relative to ‘pure’ expectations of future real interest rates. It is also market with a much more concentrated and narrower investor base than for nominal bonds. And the RBNZ – as you note – is not buying them. The Fed in contrast is buying TIPS and TIPS in general are much more liquid. If the RBNZ were to buy inflation-indexed bonds as part of its QE programme and this drove real yields lower, would this change your narrative? Probably not I suspect, which is why I’d be cautious about using them to justify arguments.

LikeLike

Yes, all fair points Nick, altho of course many of those points have been made by sceptics since first IIBs were launched and re-launched. I guess I would put no weight at all on precise numbers, and esp not those for any one day or week – I don’t think true 10 year inflation expectations are 0.4% – but equally there is pretty good reason to suppose that (a) NZ real int rates (generally, wholesale and retail) have not fallen, and (b) NZ inflation expectations, like those abroad, have fallen quite a bit. It would trouble me more if NZ IIBs were telling an anomalous story – relative to other NZ data, or other countries’ data – but they don’t seem to be (perhaps with the exception of the breakeven levels – altho that was true before this crisis).

LikeLike

Is there a theoretical link between the level of real interest rates, the level or stock of debt, and the level of productivity?

LikeLike

Not with the level of productivity but with the rate of productivity growth. A country sustaining rapid productivity will tend to sustain higher real interest rates (for various reasons). But a country may have high real interest rates for other reasons that are inconsistent with sustaining rapid productivity growth (my NZ story fits here).

LikeLike

Thanks

LikeLike

Amazing watching this RBNZ MPS conference.

1: Just a terrible incoherent chaotic feed to watch with very weak softball questioning.

2: Any talk of the consequences to depositors & savers virtually completely non existent. Gone are the days where people loved the concept of ‘compounding interest’ i guess.

Other than Bernard Hickey’s few good questions..

Notice Adrian Orr couldn’t answer Bernard’s last pertinent question Michael!

3: Why after watching this would anyone bother keeping their life savings in any bank knowing they are just going to be used as collateral damage to continue propping up the private asset mortgage portfolios for borrowers & banks

The perceived intrinsic value not only of our currency(purchasing power) but also savings being decimated every second…

I can see why physical gold pricing is at record levels and after today this will continue at pace.

LikeLike

What was the question Adrian couldn’t answer? (The sound kept breaking up and I eventually gave up, underwhelmed by the softball questioning to that point.)

LikeLike

Bernard asked Adrian “where EXACTLY was the additional $27 billion coming from? Was he going to create it or borrow it”.

Adrian….hesitated for quite a while and looking uncomfortable and somewhat flustered by Bernard’s direct question…before asking a colleague to answer for him.. The Colleague spoke the usual mumbo jumbo without again answering the simple straight forward question put to him.

I just don’t get it Michael, it’s not a secret surely so why could Adrian not just answer the question? Why can they not just be straight talkers

LikeLike

Thanks. Quite remarkable that he couldn’t/wouldn’t give a simple straightforward answer to what is really a very simple question: he’ll buy (up to) another $27bn of bonds and pay for them by issuing deposits at the RB that will be voluntarily held by the banks at a return of 0.25%.

LikeLike

Interest.co.nz did say they would put a link to the conference to again watch. Maybe someone forgot to press ‘record’, I don’t know but i can’t find it so may look on Newsroom to see if they have it there.

Honestly the last few minutes was the most interesting of the whole thing.

LikeLike

Is the RBNZ embarrassed by the term QE Michael?

Here is Bernard’s Newsroom headline:

“The Reserve Bank has nearly doubled its programme of government bond buying, which is sometimes described as ‘money printing’ or ‘Quantitative Easing for the rich’, Bernard Hickey reports”

LikeLike

You may have noticed I don’t use the term either. They use Large Scale Asset Purchase programme. “QE” tended (back in 09 etc) to emphasise the quantity of new settlement cash created – and see that as the key transmission mechanism. The Bank argues that the primary transmission mechanism is thru lowering bond yields (and they are probably right to do so – my difference with them is that having lowered bond rates, so what? It doesn’t make much difference, other perhaps than to the Crown’s borrowing costs).

Also, the bond purchases need not necessarily involve “money printing” – growth in settlement cash. In time, it is likely that some of that will be offset by short-term open market operations.

LikeLike

Ok, so no central banks like those terms, I get it & I can see Bernard maybe using antagonising language in his headline, so Michael I ask you this:

Where & when do you see an end to this kind of “solution” and a return to what we used to call ‘normal’ retail interest rate levels? (bearing in mind we are at record lows for our lifetimes)

A decade? never?

If the only direction from now on is down or negative (wholesale) then to what end? Surely this just continues to erode confidence in our currency?

What are the ‘cons’ YOU see doing this? I know you have stated the ‘pros’

The way I see it, pandemic or no pandemic we are just getting to to obvious point a great deal faster.

LikeLike

I don’t know. In the longer-run, central banks have almost no influence on real int rates at all – it is all about the structural and cyclical factors, not all well understood, that drive savings and investment preferences.

On the currency, recall that our currency (TWI) has been high for the last 15+ years (mostly) – at levels not really supported by the fundamentals. For now though the “to what end” is about getting people back to work.

On cons, there are clear distributional effects. If you are my age, you would really prefer int rates were this high or higher. If you were 35 with a big mortgage or a commercial debt, you prefer something much lower. The balance has to be set by the whole economy though.

There are uncertainties around how the deeply negative OCR would work – we haven’t done it, so we don’t know with certainty/ But we do have a fairly good idea what happens if we do little.

LikeLike

Yes, jobs need to be created fast that is for sure.

Where you are at in life ( age & assets) definitely affects ones opinion on these matter most indeed.

Just scary times now really and I’m not talking Covid (from my own point of view)

LikeLike