It must be a busy busy time in the upper ranks of the bureaucracy and their political masters as they rush to complete the Budget – due on the 14th – and whatever schemes, plans, and campaign promises the governing parties have in store for us. Between the three parties that make up the current governing majority, it is sadly hard to think of a single policy proposal in the last couple of months that might actually improve New Zealand’s woeful longer-term economic performance. Indeed, the risk seems to be that the three parties between them have in mind something more akin to a Great Leap Backwards.

But it is policy deliberation time at the Reserve Bank too. Their next Monetary Policy Statement is due on the 13th. In many respects, it should not be very interesting. After all, only little more than six weeks ago the Monetary Policy Committee firmly pledged to not change the OCR at all – no matter how bad things got – for the coming year. Quite possibly, the MPC will decide to increase its bond purchase programme, but if you think that will make much difference in macroeconomic terms, I’m sure vendors could interest you in all sort of dodgy deals (bond purchases aren’t dodgy per se, but just don’t achieve much useful and are mostly political theatre here in the current context).

What the Monetary Policy Committee should be doing is quite another matter. When they made that rash commitment not to cut the OCR any further, no matter what, for at least a year, the Governor was still in some sort of alternative reality: at the press conference after the announcement he was refusing to concede that New Zealand would necessarily experience a recession, and seemed to have no conception of what was already breaking over the world and what was about to break over New Zealand. He wasn’t alone – this was, after all, still in the days of mass gatherings that even the PM was keen on – but he and his Committee are the ones charged with the conduct of monetary policy (I was going to say “responsible for monetary policy”, but the Act is quite clear that the Minister of Finance shares that responsibility).

The economic situation has got a whole lot worse since then. And that is so even if you are optimistic that New Zealand might soon emerge to the government’s “Level 2” – whatever that will specifically mean by the time we get there. Apart from anything else, the rest of the world – including China – is in the midst of a very severe economic downturn. Recall 2008: there wasn’t too much initially wrong here, but a very sharp global downturn still had big adverse ramifications for us and our economy, that took years to recover from.

And with the deterioration in the economic situation, confidence that the Bank will deliver on the inflation target the government has set for it has also drained further away. That was a risk that greatly concerned the Governor only six or eight months ago when the MPC acted boldly last year. It should concern him/them much more now when are actually in the midst of a savagely deflationary shock (globally).

Westpac’s economics team had an interesting note out earlier in the week in which they noted – correctly in my view – that

In our assessment, the RBNZ is going to have to deliver much more monetary stimulus.

They still seem to be believers in the bond purchase programme but argue that even after an increase in that programme

In our assessment even more monetary stimulus will eventually be required.

They now expect that the Reserve Bank will move to a modestly negative OCR, in November.

As they note, there are two possible obstacles. The first is this claim the Bank keeps making that “not all banks’ systems can cope with negative interest rates”. Westpac – being a bank I guess- seems to think this is some sort of adequate excuse. I certainly don’t. Even allowing for the Governor’s utter negligence in not having ensured all systems were in place – the Bank having been aware of the possibility of negative rates for years – it is simply inconceivable that any significant financial institution can be unable to cope with the sorts of modestly-negative OCR levels Westpac is talking about (-0.5 per cent). Perhaps they and the Reserve Bank really have been remiss and some banks’ retail systems or documentation aren’t really positioned for negative retail rates, but with term deposit rates above 2 per cent and lending rates a lot higher than that, negative retail rates simply aren’t a material issue at present if the OCR is only going to go to -0.5 per cent. We need the additional monetary policy support now, not months from now when the Bank and the banks might finally have sorted things out. Institutions that might not be able to cope should simply be left exposed.

And Westpac again

The second impediment is that lowering the OCR this year would break the RBNZ’s commitment to keep the OCR at 0.25% until March 2021. The RBNZ could probably hold its head high by pointing out that the Level 4 lockdown was a truly extraordinary event, and we doubt they would come in for much criticism. However, any move to break an earlier commitment would have to be carefully explained and justified.

I don’t think any of that makes much sense. If the Bank on 16 March didn’t realise the risks ahead of them – lockdowns weren’t exactly unknown globally by then, and a sharp downturn was on its way anyway – the MPC members simply aren’t fit to do their job. Of course, they could shamefacedly say “Oops, sorry, looks like we made a pretty bad misjudgement, and we now need to change course”, but actually acknowledging error isn’t the official style, let alone Orr’s. And as for “carefully explained and justified”, well maybe, but Orr’s style so far has been nothing like that – we’ve just seen one lurch after another (recall the 50 basis point cut last year, not foreshadowed at all) where they mostly make up the rationalisations after the event.

We get to a similar bottom line I guess….and I suppose Westpac has to be more respectful of the Bank or else senior officials might (a) stop talking to them, and/or (b) complain to the chief executive.

Westpac expects that Bank will walk away from the “no cuts for a year” line in August, preparing the way for an actual cut in November – six months from now.

A journalist asked me yesterday if I thought they would abandon the pledge in May. My response then was a quick no – it seemed too close to when the pledge was first made, and to walk away at the first opportunity would deeply degrade the value of any future forward guidance commitments the MPC might offer. But on further reflection I wonder if there isn’t more chance than I initially thought that they will simply walk back much of the “no cuts” commitment this month. After all, their messaging and policy haven’t been consistent and discplined through time in the MPC’s first year, so why suppose it would start now? And, realistically, against this economic backdrop it just looks silly to continue to pledge not to cut the OCR come what may. After all, some journalist might actually ask hard and persistent questions challenging the Governor to justify that bizarre pledge (not likely, but you never know), and that might be a challenge even for our loquacious Governor. Then again, maybe we would simply get handwaving and more claims about all the good the bond purchase programmes have done – bluster over analysis

And there seems to have been something of a change in market sentiment too. The 90 day bank bill rate has fallen by 17 basis points since mid-April and is now at a level consistent with markets pricing a reasonable probability of an OCR cut at some point in the next three months. Longer-term rates are falling too – the 10 year nominal government bond yield this morning was a mere 0.69 per cent.

But long-term bond yields don’t really matter much in New Zealand – to anyone other the government, It isn’t as if there are lots of long-term fixed rate mortgages repricing off the 10 or 15 year bond rates.

And if wholesale interest rates have been falling this week, the exchange rate hasn’t been. In fact, yesterday’s reading of the TWI was less than 5 per cent below the December average – and in those far flungs days people were getting upbeat about economic prospects here and abroad this year. Back on 16 March, the Governor claimed the exchange rate was doing its “buffering” job…….but not really very much at all, relative to the scale of the shock.

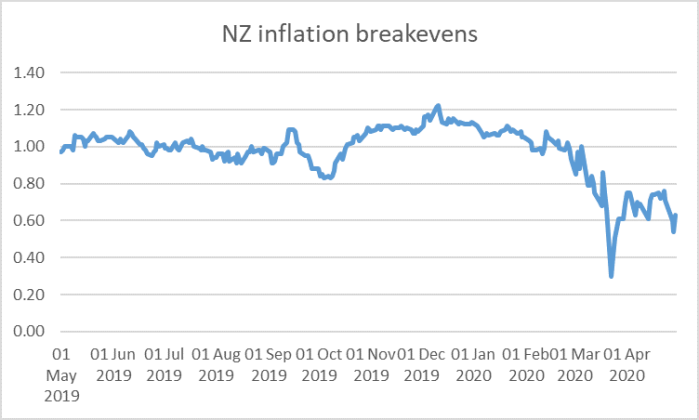

And what about inflation expectations? If there was a modicum of relief in the specific inflation expectations questions in the ANZ Business Outlook survey yesterday, there was none in the “pricing intentions” results (or, for that matter, in the volatile ANZ consumer expectations measures out today). And what of the wholesale markets? This is the chart of inflation breakevens – the gap between nominal and indexed 10 year bond yields.

These implied expectations had already fallen away quite a lot over the last few years – a 1 per cent average of 10 years is just not even close to the 2 per cent target – but have dropped away quite a bit further since then (five year breakevens are even lower). And recall that these are the same upbeat global markets that now have equity markets showing strength that puzzles most economic analysts: it is hardly as if an excess of gloom is currently driving markets.

It also isn’t just some New Zealand idiosynrasy – thin markets and all that. The drop in the implied US breakevens is of similar magnitude to that in New Zealand (and I happened to watch a webinar yesterday run by Princeton economics department and in an online poll of their viewers, the breakeven numbers weren’t regarded as out of line with reality).

In other words, real retail interest rates have not come down much at all, the exchange rate has not come down much at all, and inflation expectations have been (a) falling and (b) always well below the target midpoint. Add in the unemployment we are seeing, rising by the day, it is a standard prescription which in normal times a central bank would see as a pretty compelling basis for a much looser monetary policy.

With an economy that has been shrinking fast, and seems set to remain well below normal for quite some time, it remains pretty extraordinary that both term deposit rates and low-risk retail lending rates (conventional variable mortgage rates) are still materially positive in real terms. Run your eye down the term deposit offerings listed on interest.co.nz and the big banks are typically still offering 2.3 per cent for six months, and their standard variable rate mortgage seems to be priced between 4.4 and 4.6 per cent.

Cross-country comparisons of retail rates are hard – product features differ etc, and our sort of variable rate mortgages are largely unknown in the US – and so I rarely do them. But I thought some Australian comparisons might be relevant – after all the RBA’s policy rate is also 0.25 per cent. But the gap between the policy rate and retail rates is larger here than in Australia.

Thus, whereas ANZ in New Zealand is offering 2.3 per cent for NZD six month deposits, ANZ Australia isoffering 0.9 per cent for AUD six month deposits. Westpac NZ is also offering 2.3 per cent, while in Australia they are also offering 0.9 per cent.

For a variable rate mortgage, ANZ locally is offering 4.44 per cent. In Australia, ANZ will lend Australian dollars on a variable rate mortgage at as low as 2.72 per cent (although there is myriad of product offerings). The best Westpac offering I could see (in Australia) was a bit higher, but still a long way below Westpac’s New Zealand variable rate of 4.59 per cent. This issue here is not about bank margins (between borrowing and lending rates) but about monetary policy, which influences the overall level of rates.

And if Australian nominal retail interest rates are lower than New Zealand’s, recall that the RBA’s inflation target is centred higher than New Zealand’s – centred on 2.5 per cent inflation – so that in real, inflation-adjusted, terms the gap in favour of Australian’s retail customers is even greater. Now, to be sure, Australian real retail rates are usually lower than New Zealand’s – all New Zealand’s real interest rates generally usually are – but when we have a larger adverse shock than Australia, that shouldn’t be the case right now. And when the Governor tries to tell us – as he tried to tell Parliament – that New Zealand interest rates are as low as they can go, he is simply wrong. Real retail interest rates are far too high for this economic climate and need to come down.

Getting them down further remains technically easy. Simply lower the OCR to -0.5 or -0.75 per cent and there will be no large-scale transfer to physical cash. And as I’ve argued before dealing with the large-scale cash conversion risk is also relatively trivial as a technical matter. The Reserve Bank simply refuses to do it, and the Minister of Finance apparently refuses to insist on it. In this climate – and given the margins between the OCR and retail rates in New Zealand – an OCR of -5 per cent would be more appropriate, and if it were implemented decisively – lowering the exchange rate, boosting inflation expectations, easing servicing pressures (why all the focus on rents, and almost none on interest rates?) and signalling a climate supporting a quick return to full employment – the extremely low rates might not even be needed for long. But stick around current levels and the growing risk is that it takes many years to get off the lows, and inflation expectations keep drifting down, reinforced by repeated weak actual inflation outcomes.

The MPC on 13 May should:

- abandon the “no change for a year pledge”,

- cut the OCR to zero,

- announce that the OCR will most likely be cut further in June (which would get many of the benefits immediately, but give a little time if there are some real system issues re a negative OCR), and

- commit to have in place by June robust mechanisms that for the time being removed, or greatly eased, the current effective lower bound on short-term wholesale interest rates.

An apology would be good too, and some long-overdue openness from the invisible – but supposedly accountable – external members. But I won’t push my luck. If they got the substance of policy right now, the past failures could be largely set to one side.

(Oh, and if they wanted to they could offer to buy some more government bonds, but get the basics right and the theatre won’t be necessary.)

Down the Bottom “The MPC ….. 13 May ??? …. just wanted to show I read the whole article 🙂

Cheers

Marcus

On Fri, May 1, 2020 at 12:38 PM croaking cassandra wrote:

> Michael Reddell posted: “It must be a busy busy time in the upper ranks of > the bureaucracy and their political masters as they rush to complete the > Budget – due on the 14th – and whatever schemes, plans, and campaign > promises the governing parties have in store for us. Between” >

LikeLike

Oops.

thanks (now corrected)

LikeLike

Don’t focus on the 6 month mortgage rate – that is the mugs rate. The one year ‘special’ rates are around 3 percent.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m not – 6mth TD rate (because that is the time series the Bank publishes), but the variable mortgage rate, because that is the one most closely tied, albeit with wide margins, to what mon pol directly influences.

LikeLike

The 1 yr rate is where the money is – and also has been influenced by the OCR

LikeLike

Horses for courses: my focus is on the overnight rate and stuff the Bank has actually done. The whole retail yield curve matters for other purposes.

LikeLike

As it happens. one year mortgage rates don’t appear to have fallen much more than floating rates.

LikeLike

“An apology would be good too.”

Moving into comedy?

LikeLiked by 3 people

Hi Michael excellent piece today. I couldn’t agree more with you on NZ retail rates, it’s a bloody disgrace where NZ rates are vs Australia. I am amazed no opposition politicians have picked this discrepancy up and hammered the RBNZ on it. Right now mortgage rates 100bps lower are urgently needed.

LikeLike

Wound not most bank systems have adjusted to negitive rates inside there capital market systems during past euro GFC events…. NZ int rate swaps may be an issue ….

LikeLike

Why does Orr keep harping on about fiscal policy having to do the heavy lifting – surely a high proportion of the businesses (including landlords) and households in financial difficulties have a reasonably large interest bill?

Conversely, those earning an income from interest are unlikely to be in any financial difficulty particularly when there is not much more than the basics to spend money on at the moment?

LikeLike

Lowering the interest will help, but the debt still has to be repaid, and for businesses, normally 5-7 year terms mean the principal is the biggest issue, not the interest unless the business is big enough to negotiate something better than standard.

LikeLike