The Reserve Bank Monetary Policy Committee releases its next Monetary Policy Statement and Official Cash Rate (OCR) decision next Wednesday – the first we’ve heard from them since November.

Until a couple of weeks ago you could probably mount a pretty strong case for the status quo. If the MPC was right to have left the OCR unchanged at 1 per cent in November, it probably looked as if that was still going to be the right decision in February. I thought they should have cut in November, and so was still inclined to think they should cut now – but it wasn’t a particularly strongly held view. It is worth remembering that after all these years, the Bank’s favoured core inflation measure still isn’t back to 2 per cent (it was last there in 2009) and there wasn’t a lot in the wind suggesting it was likely to rise further. But there hadn’t looked to be a lot in it.

The Reserve Bank’s Survey of Expectations, released at 3pm today, looks to be not-inconsistent with that sort of status quo story. But the survey closed a week ago, and opened two weeks ago – the Bank doesn’t tell us when responses came in, but I know I completed mine on 25 January.

Since then coronavirus has become a huge story. From an economic perspective, the issue isn’t so much the number of deaths – 50 or so in total two weeks ago and 640 now, on official figures – as the policy and personal responses, here (and in other similar countries) and in China. Two weeks ago, perhaps optimists might have hoped a one week shutdown over Lunar New Year might break the back of the problem. But then, of course, ever more cities in China were locked down, the PRC authorities banned most outbound tourism, countries starting putting restrictions on arrivals of non-citizens who’d been in the PRC, and finally New Zealand – apparently dragged along by Australia – banned the arrivals of anyone other than citizens (and their close family members) who’d been in China recently. We’ve also seen dairy product prices falling, talking of serious disruption in the logging industry, and so on. We’ve even seen some more-domestic effects, including the cancellation of the Lantern Festival in Auckland. Oh, and there seems to be no sign in the PRC responses that suggests they think they’ve already got on top of the problem.

No one knows how long these effects will last, or whether things may yet get (perhaps materially) worse from here (I was talking to a journalist the other day about possible extreme scenarios, and it doesn’t really do to contemplate what would happen to world trade – perhaps only for a short period – in such scenarios).

When I say ‘no one”, that of course includes the Monetary Policy Committee, who will have not a shred more information on the underlying situation – and probably very little more on domestic economic effects – than you, I, or anyone else. Any data available just yet – perhaps daily air arrivals, or electronic transactions volumes in (say) Queenstown – will be fragmentary at best, and there won’t even be new local business survey data for a few weeks. So they have to work with what we know, perhaps how things would be likely to play out if the policy responses (here and abroad) remain much as they are for any length of time, and within a framework for thinking about risk and regret.

All of which looks a lot like the classic sort of shock monetary policy is designed to help manage (lean against). Aggregate demand in New Zealand will take a not-insignificant hit: tourism and export education from the PRC is about 1 per cent of GDP, and tourist numbers will dry up almost completely for now, and (if our numbers are similar to those in Australia) the export education numbers are likely to more than halve.

These effects might not last long, but they are the situation we face now and no one has any idea how long the adverse effect will last.

But these aren’t the only demand effects. Australia and the PRC are our two largest overall export markets: economic activity in China is likely to have taken a substantial hit this quarter, and Australian universities are (for example) even more dependent on the PRC student market than the New Zealand ones are.

And how would you respond to uncertainty if you were in business, or were (for example) a lending institution. The rational response is to put projects on hold where possible. That seems likely to happen – perhaps on a very small scale initially (few new projects start each week, but mounting as the situation becomes more protracted (and perhaps doubts grow about just how quickly business might rebound).

Also, although the focus to date has been on services exports (tourism and export education), and a couple of goods export sectors, even if goods can be still shipped out to China, you have wonder how soon the flow of imports is going to be affected – people who’ve been in China in the last 14 days can’t enter Singapore, Australia, PNG, Fiji, Taiwan or…..New Zealand (and, I understand it, much of New Zealand’s trade is trans-shipped through Australia or Singapore). Ships need sailors.

I don’t know what the Reserve Bank will have chosen to do about their formal economic forecasts. In their shoes, I’d probably publish ex-coronavirus forecasts, and then a series of scenarios around coronavirus effects (what else can they do: they usually treat other policies as a given, and in this case the ban of people who’ve visited the PRC is scheduled to lift next Sunday, but I doubt anyone much expects it will be, and more importantly neither they nor anyone else can credibly forecast the path of the virus, including how its is beginning to spread outside China).

But whatever they do in the body of the document is much less important than the policy call they make. This is the time to cut the OCR. perhaps even by 50 basis points. It would be a mix of risk-mitigation and responding to a real loss of demand (very rarely do we see such hard early evidence of a specific source of demand drying up so quickly).

The standard counter-argument is something along the lines of “early days”, “likely to rebound quite quickly – eventually”, and so on. But here is the thing about monetary policy: it can be adjusted quickly (to cut and to raise); it is the tool designed for short-term macro-stabilisation (unlike fiscal policy) and some of the channels – notably those to the exchange rate – work really quite quickly. I’m not suggesting that cutting the OCR would make more than a trivial difference to GDP in the March quarter (the tourists and students still won’t have come), but if the effects are any longer-lasting we would start to see the benefits.

Twice before the Reserve Bank has cut the OCR is response to truly-exogenous external events. The first was the unscheduled 50 basis point cut in September 2001 (a week or so after the terrorist attacks). Here was the case we made then

“It seems more likely now that the current slowdown in the world economy will worsen. In these circumstances, New Zealand’s short-term economic outlook would be adversely affected, although any downturn might well be relatively short-lived.

“New Zealand business and consumer confidence will be hurt by recent international and domestic developments, and today’s move is a precaution in a period of heightened uncertainty.

I still reckon that was an appropriate response at the time, even though we had (a) no new survey or hard data, (b) there were no foreign or domestic government restrictions which would have the direct effect of biting into domestic demand in New Zealand and (c) the exchange rate – already low – was by this point almost 5 per cent lower than it had been on 11 September. It was explicitly precautionary, but in a climate where our best judgement told us that if there was any effect it was going to be adverse (disinflationary).

The second such 50 point cut was in March 2011, after the severe February earthquake. As the Governor put it at the time

“The earthquake has caused substantial damage to property and buildings, and immense disruption to business activity. While it is difficult to know exactly how large or long-lasting these effects will be, it is clear that economic activity, most certainly in Christchurch but also nationwide, will be negatively impacted. Business and consumer confidence has almost certainly deteriorated.

Going on to observe

We expect that the current monetary policy accommodation will need to be removed once the rebuilding phase materialises. This will take some time. For now we have acted pre-emptively in reducing the OCR to lessen the economic impact of the earthquake and guard against the risk of this impact becoming especially severe.”

We knew that the longer-term impact of the earthquake would be a big positive boost to demand (all that rebuilding activity, which would crowd out other activity in time) but still concluded that it was appropriate to cut early and quite hard to lean against adverse confidence effects etc (and some direct adverse demand effects – eg to South Island tourism). Perhaps we just got lucky, but it still looks like an appropriate response to me, even with years of hindsight.

In June 2003, SARS also played a role in the Bank’s decision to cut the OCR then. I wasn’t involved in that decision – I was working overseas – so don’t have as strong a sense of the balance of factors. One can mount an argument that it was unnecessary to have cut – the Governor eventually concluded as much – but much of that argument was with the benefit of a hindsight that real-time decisionmakers could not have had (about how quickly the virus would be contained).

Set against the backdrop of those three cuts, I reckon the case for an OCR cut now – even it had to be pullled back in six months’ time – is stronger than in any of those other cases. We have clear adverse domestic demand effects, that aren’t just about confidence but about policy choices in China and in New Zealand (and, more peripherally, in other countries), we don’t just have a one-day event which we live with the aftermath of (rather an ongoing situation, which is probably still worsening), the epicentre of the issue is in the world’s largest or second-largest economy which itself is taking a large negative economic hit for now, and Australia – our other main trading partner, and major source of investment – faces very similar issues to New Zealand.

Against that backdrop, it isn’t obvious what the downside would be to an OCR cut next week. Core inflation is still below the target midpoint, and yet the demand shock is adverse. Perhaps things resolve themselves very quickly in a couple of months and the Bank is slow to pull back the OCR cut. The worst that could happen then might be core inflation going a bit above 2 per cent. But since 2 per cent isn’t supposed to be a ceiling, and we’ve haven’t even been to 2 per cent in the last decade, that might count as a gain not a loss, in terms of supporting core medium-term inflation expectations.

Then, of course, think about really bad scenarios, and a world with very limited fiscal and monetary policy capacity to respond to a serious downturn. It really is important to keep those expectations up. Recall that that was one of the stories the Reserve Bank told for a while after the unexpected 50 basis point cut last August.

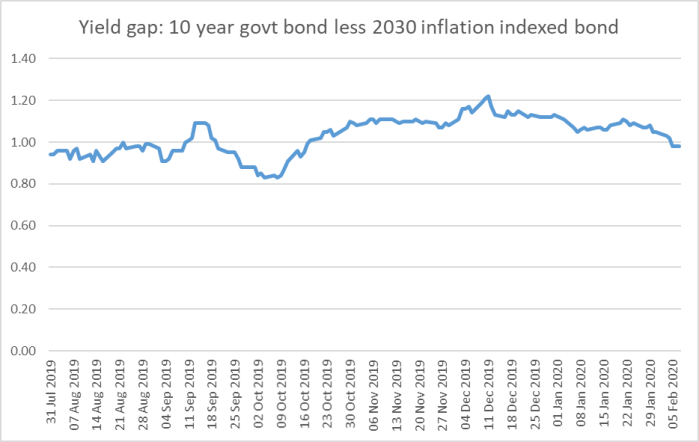

But here is the implied inflation expectation measure from market prices, right up to today (the difference between yields on nominal and indexed 10 year government bonds)

There was a bit of lift in this measure of implied expectations late last year (partly global, but a range of central banks were responding similarly). But now we are pretty much back to where we were before the Bank cut the OCR unexpectedly sharply six months ago (and this even after bond yields have bounced off their lows earlier this week). I guess we should take some comfort that implied expectations aren’t lower than those in August, but 0.98 per cent is a long way from 2.

And as one last straw in the wind, in 2017 the Bank (helpfully) added a couple of questions asking about respondents expectations for inflation five and ten years hence. The answers have hewed pretty close to 2 per cent – I usually put in 2 per cent for 10 years hence, noting that the current MPC/government won’t have any effect on those outcomes – but when I opened the survey results today I noticed that even these expectations (which the Bank likes to boast of, as a sign of confidence) have been edging down.

The differences are small, and in isolation I wouldn’t put much weight on them. But not much is moving in the right direction, and these results were surveyed two weeks ago when most respondents thought the policy status quo was just fine for now.

It seems a pretty obvious call to me that they should cut on Wedneday – absent some startling positive turn in the virus and related news between now and Wednesday morning – rather than just idly handwringing about “watching and waiting”. And the Governor/MPC was willing to make some big and unexpected calls (wisely or not) last year. The Bank wouldn’t be the first central bank to move either.

Who knows whether or not the Bank will actually move on Wednesday – quite possibly not even them yet – but I’m sure the MPC will have been looking for some analysis of past responses to out-of-the-blue shocks and thinking about the similarities and differences here. Whichever path they finally choose, that thinking should be laid out – not just noted – in the MPS and/or the minutes.

Would not the potential for scarcity in the flow of certain goods ex-Asia have the potential to increase local prices – and hence inflation? Isn’t it about time the RB met its inflation target?

The government has plenty of fiscal policy initiatives it could bring forward immediately. I’d rather the government responded to such external shocks, as opposed to the RB. New Zealand would not necessarily be worse off for learning how to deal with weaker demand from China.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry, I meant meet the long run midpoint as an average. Low inflation/deflation seems to be more of a problem as per the points made here;

https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/research-and-publications/seminars-and-workshops/inflation-targeting-prospects-and-challenges

LikeLike

I agree with Katharine, no cut required to OCR The RBNZ does not need to cut. The Chinese banks are still offering fixed interest rates at 3.15%. The Australian banks are pushing upwards towards 3.5% as they are trying to make a point that the RBNZ increased capital requirements will force interest rates up. Any OCR cut will not influence the Australian banks to cut.

Sharemarkets are already rising in value in anticipation of the Chinese governments response which likely means pumping billions more cash into the Chinese economy to kickstart after the extended Chinese Lunar holidays. I don’t think they can maintain a lockdown on so many cities longer than a month. The potential for mass Civil unrest and police brutality due to the lack of provisions will rise the longer the lockdown.

LikeLike

There could be some shortages like that that could boost some prices but that effect is likely to be swamped by (a) the loss of demand and (b) cheaper local prices for commodities otherwise sold to China (crayfish as just one tiny example, but also I imagine hotel rooms in Queenstown or Rotorua).

LikeLike

Radio news last night the hotel industry are lobbying government for help – Auckland, Rotorua and Queenstown – MSM silent so far

LikeLike

Not exactly the best time for Phil Goff to be announcing a bed tax. Auckland Council does come across as greedy to fund its executive pay increases as Chinese visitors numbers drop over a cliff.

LikeLike

The LNG industry is now on an edge.

This is not going away in a hurry. China doesn’t care what it does to its people and if they starve then that’s the price of survival of the current dynasty. And its all about that survival.

https://ysb.co.nz/gasmaggedon-sweeps-over-global-energy-market/

LikeLike

Oh, and fiscal policy is a lot slower to deploy (and unwind): better suited for longer term issues whereas a virus is most likely to be a 2-12 month thing).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Household deposits in banks equal to Household debt. Increasing or decreasing interest rates will not increase domestic consumer demand overall. Therefore lowering interest rates has the largest impact on increasing businesses bottom line profit and encouraging businesses to expand but given that Chinese demand has pretty much fallen over the cliff businesses will not invest nor expand.

Banks are still very tight with lending due to increased Capital requirements and LVR equity restrictions. Faster impact by lowering the equity restrictions on LVR.

LikeLike

Lowering the equity restrictions will boost the property market with increased credit liquidity. The impact to demand will be almost immediate as the property market is already positioned to rise.

LikeLike

Roger J Kerr – September 2019

In slashing the OCR interest rate by 0.50% to 1.00% on the 7th of August, the RBNZ stated that they wanted to stimulate business investment and confidence by making the cost of debt cheaper. So far, it seems that they have scored an “own goal” and achieved the exact opposite.

How has that August cut played out. Has business investment responded.? How much.?

Domestically, interest rate movements create beneficiaries and victims in equal amounts. It is a zero-sum-game. An immediate 50 bps cut would simply amount to feel-good gesture politics. A transfer from one group to another. Savers incomes would be cut and would spend less. Borrowers would simply pay down debt. For forestry companies with logs sitting on wharves a rate cut would only be of benefit it they are carrying debt. If no debt, the cut will not move the logs. Shipping companies – same.

Helicopter money wouldn’t help. TARP would help targeted businesses-industries

LikeLike

Reasonable people can debate these things, but my perspectives:

– it is hard to tell how much difference any OCR change makes, partly because they are supposed to lean against things already underway (so investment might not rise when OCR cut but might fall away less than otherwise). Standing back after 6 mths, I don’t think many economists would think the Aug move was an “own goal”, even if the comms/messaging at the time was terrible.

– OCR cuts are not zero sum games. They don’t work by “compensating” individual adversely affected industries/firms, but by shifting incentives to towards spending now rather than later, and by lowering the exch rate (encouraging prodn and consumption locally, rather than abroad).

Note that in suggesting a cut now I’m not suggesting some catastrophic econ decline. In serious recessions the OCR tends to drop 500bps. A cut now or in March simply leans a bit against a downturn, and implicit says interest rates don’t now need to be quite as high as seemed previously to get inflation to 2 per cent. That shld always be the test.

LikeLike

Chart trends indicate that the OCR has a massive influence on the 90 day bank bill rates. Also Treasury bond rates appear to be closely linked to the OCR. Mortgage interest rates are much less tied to the OCR with residential floating interest rates still around 5% and 2 year fixed around 3.5% Most small businesses rely on the residential overdraft facilities to fund working capital.

In terms of household savings and deposits, they almost equal which means the net effect to available funds to fund consumption is a zero sum game. In terms of the affected number of people, there are significantly more savers than there are borrowers which suggests a lower OCR reduces demand sentiment overall.

However, businesses that rely on debt which is pretty much most NZ businesses will see improved bottom line profits which allow for individual workers job security and pay increases. Note that retained earnings is not cash savings in businesses. The OCR has a much more direct impact to business investment decisions than on overall household demand.

Note also.that reasonable people are not all financially literate.

LikeLike

Curious that the National party is seeking to ensure that New Zealand is more economically reliant on China in the future (although to be fair they seem to have absolutely nothing else in the way of ideas on how to improve the economic prosperity of New Zealand):

https://www.newsroom.co.nz/2020/02/02/1011349/the-man-who-would-be-finance-minister

“How will doing more of what we’ve done for the past three decades finally make us wealthy? I asked. Goldsmith offered no explanation.”

The obfuscation, lack of transparency and mixed messages from China/CCP with this latest crisis would seem to indicate that the prudent strategy would be to reduce economic exposure to China. Clearly the collective wisdom of the National party caucus thinks otherwise.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thanks for the prompt to finally read that interview. It really is deeply underwhelming. In a way, I guess that shouldn’t be too surprising, but one always hopes that some day one of them (our political leaders) will offer something serious and different.

LikeLike

Check out David Seymour.

Only MP saying anything sensible.

LikeLike

I’m in Singapore visiting clients here then in Hong Kong and London. One or two businesses have said they want to do a conference call rather than face to face bit they are the exception. The schedule is (mercifully) full.

What’s interesting here is that there are now instances of panic buying and hoarding of staple items such as rice, toilet paper etc. I imagine that dairy products are also flying off the shelves. I think for NZ, dairy won’t be that badly impacted – people can store it and still need to eat – it will be highly perishable items (vegetables), or durable materials that go into construction (logs) and services (education/tourism) that will be more severely impacted.

To me, this is a supply and demand shock in cHina, but largely a demand shock outside. We don’t know how long it will last or how deep it will be, so we can only do scenario analysis, but the figures I’m coming up with are pretty large, and with each new city quarantined and each day prolonged, the shock is deepening.

I’m probably less inclined to urge a rate cut at this point, but the Statement and tone should be very cautious… and the Bank should indicate clearly all meetings are live. That way, the market can price a cut in for the OCR review if necessary.

LikeLike

Thanks Peter. Certainly one of those issues reasonable people can differ on, but when there is an unambiguous negative demand shock (as we agree is primarily the case outside China) then if one thought the OCR was roughly right pre that shock, the case for a cut – even if ended up being quite shortlived – seems reasonably clear. Sure we don’t want mon pol generating shocks, but we also don’t – for now – need the OCR as high, to get/keep inflation near target, as seemed the case a month ago.

Enjoy your trip: I hope you don’t find yourself compulsorily self-quarantined when you get home, having visited HK in the previous 14 days (not the situation yet, but easy to see how that could change quite quickly).

LikeLike

Apartment buildings are cramped conditions and with shared air conditioning ducting. The problem is we do not know how the novel corona virus is spread. If it is an airborne then the way the Chinese government is keeping people stuck in camped conditions and stale air conditioning can only accelerate the rate of the spread.

LikeLike

While changing interest rates may help the real issue is to make Kiwi businesses more profitable with a greater amount of cash in the till.

Doing that requires our investment in new and better plant.

The way to achieve that is to change the depreciation rates. Singapore Air can depreciate a new plane in 5 years, Airnz it takes 15 years and the same for all our plant. (and I don’t include cars in this.)

Change our depreciation rates and lower our tax rates and watch the business grow.

Oh and stop subsidizing those that bleat and screw the pollies, e.g. Weta and Amazon etc.

https://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/news/article.cfm?c_id=3&objectid=12306788

Lowering interest rates is simply not going to make business work smarter.

If I have a 100k loan the difference could be $20 a week.

Less than a lunch snack.

At $1mill that’s only $100 a week. Chicken feed. No one makes a business decision on that kind of margin.

Simply not going to make a difference.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Perfect example – great idea.

LikeLike

Hi Michael, just a thought: isn’t one response here targeted fiscal assistance? It feels like at this stage it’s certain industries that look likely to come under intense (possibly short term but we don’t know) pressure, but the rest of the economy is doing ok (a big “if” that this remains the case I know).

LikeLike

I guess my main focus was on the issue facing the RB, which has to take everything else (incl fiscal policy) as given and react accordingly.

Generally, monetary policy isn’t well suited to targeting particular industries/people (the upside is that it is pervasive in its effects, and quick to adjust), which direct govt payouts can do. I’m generally sceptical of the case for the latter, except thru the welfare system – businesses need to structure themselves to cope with temporary disruptions. It would be harder to use the direct payout route than, say, immediately post Feb 2011, because (a) adversely affected firms are quite widely dispersed (think tourism) not geographically concentrated, and (b) because we aren’t beginning a defined recovery phase, indeed things might yet get much worse.

In practice, perhaps there will be elements of both (I certainly expect the govt will provide financial support to universities, altho that is a slightly different case since the govt is also in effect the owner).

LikeLike

[…] Bank has cut the OCR in response to truly-exogenous external events,” Reddell wrote in a blog post, pointing to 50 basis point cut after the 9/11 attacks and the Christchurch […]

LikeLike