Not unlike the OECD, our Productivity Commission tends to lean left. Not usually in some overtly partisan sense, but in a bias towards government solutions, a disinclination to focus on government failures as much as “market failures”, and a mentality that is often reluctant to look behind symptoms (which government action can sometimes paper over) to look at deeper causes and influences.

Sometimes the cheerleading for the left becomes more overt. There was a streak of that evident in their climate change report a year or two back, but it seems particularly evident in their latest draft report out this morning. Reflecting the change of government, the political complexion of key personnel of the Commission, the Commissioners – while each individually capable – appears to have shifted leftwards.

The Productivity Commission’s inquiries are into topics selected by the government of the day. The current Minister of Finance has been keen on his “future of work” theme for years, dating back at least to when he became Labour’s Finance spokesman. Now that he is Minister of Finance he is able to get the taxpayer to cover work in this area. Here are the terms of reference for the current inquiry into “Technology disruption and the future of work”.

Apparently prompted by the government, the Commission appears to have begun releasing draft reports in stages. This seems a useful step forward: potential readers or submitters might be faced with a series of 100 page drafts, not the single 500 page behemoths that the Commission often used to produce. The draft report released last night (“Employment, labour markets and income”) is the second of five as part of this inquiry.

What it boils down to, amid various reasonable insights, is a push for a much bigger welfare state, allegedly in the cause of lifting average New Zealand productivity (and sustainable wages), without a shred of evidence or careful considered analysis connecting one to the other. It is the sort of thing you might expect a political party to come out with – the Labour Party conference, for example, is meeting shortly – but not so much independent bureaucrats supposedly focused on productivity.

This, from the Commission’s press release, is the gist of what they are about.

I heard Sweet on the radio this morning playing up the contrast – beloved of people championing flexicurity- between “job security” and “income security”, claiming that New Zealand has the former (“a bad thing”) but not the latter.

The mental model that appears to be driving the Productivity Commission in this draft report is one in which we have an excessively rigid labour market, with people (and society) reluctant to face job change, and that this in turn is a big part of the reason why business investment has been low, and productivity growth has fallen far behind. There is little or evidence adduced to support these claims, let alone the next leap that if only people were given more money more readily when they lost their jobs we’d be well on the way to solving our productivity failings.

Here is the Commission’s summary of the good and the bad, as they see it, of New Zealand’s labour markets (from p21 of their report)

It isn’t obvious that low labour productivity is particularly a labour market issue, but setting that to one side for now, I wouldn’t disagree with any of those bullet points. But I’d look at the first group (“the good”) and be inclined then to suggest that this wasn’t the area to be looking if I was trying to do something about (a) economywide productivity growth or (b) adoption of new technologies by firms. Our labour market looks pretty flexible and responsive. The Commission itself says so.

So why then the push for much higher welfare payments (call them “social insurance” if you like) to people who lose their jobs, less means-testing etc etc? It can’t be economics – facilitating ready movements of people from one job to another etc – so it really has to politics; a view on a different set of income distribution arrangements. That is stuff elections should be fought over. But it simply isn’t that credible that the absence of these very general northern European approaches is causally connected to the failures of productivity here (except perhaps in the reversed causation sense that richer and more productive countries may choose to be more generous).

The Commission is dead keen on us following the example of Denmark, the Netherlands, and Sweden. These are all highly productive economies (which appear in the grouping of top tier countries – northern Europe and the US – I often use here in productivity comparisons). But it isn’t obvious that their labour markets function betters than ours does. I’ve shown some comparisons re Denmark previously, when Grant Robertson in Opposition was touting the Danish “flexicurity” approach. In that post, I concluded

I imagine that life on the unemployment benefit is a bit more pleasant in Denmark than in New Zealand, but it isn’t obvious that the Danish structure, as a package, is producing, over time, better outcomes than what we have here. And their model is vastly more expensive, and more heavily regulated, consistent (of course) with Denmark’s position as the OECD country with the third largest share of government spending as a per cent of GDP (57 per cent). New Zealand, by contrast, has total government spending of around 41 per cent of GDP

Perhaps more regulation and more spending was Robertson’s point. I guess we have elections to debate such preferences, but it seems a stretch to believe it would be an approach that would make our labour market function better. It isn’t obvious Denmark’s does.

But lets update the comparisons and extend them to include the Netherlands and Sweden as well.

First, take a look at the OECD’s indicators around employment protection legislation. Recall the Commissioner claiming New Zealand has “job security” and suggesting we need to move further away from that. Well, here are the comparisons.

| The OECD indicators on Employment Protection Legislation | |||||

| Scale from 0 (least restrictions) to 6 (most restrictions), last year available | |||||

| Protection of permanent workers against individual and collective dismissals | Protection of permanent workers against (individual) dismissal | Specific requirements for collective dismissal | Regulation on temporary forms of employment | ||

| Denmark | 2013 | 2.32 | 2.10 | 2.88 | 1.79 |

| Netherlands | 2013 | 2.94 | 2.84 | 3.19 | 1.17 |

| Sweden | 2013 | 2.52 | 2.52 | 2.50 | 1.17 |

| New Zealand | 2013 | 1.01 | 1.41 | 0.00 | 0.92 |

New Zealand’s legislation around employment protection is more liberal on each measure than any of these flexicurity countries – quite materially so in most cases.

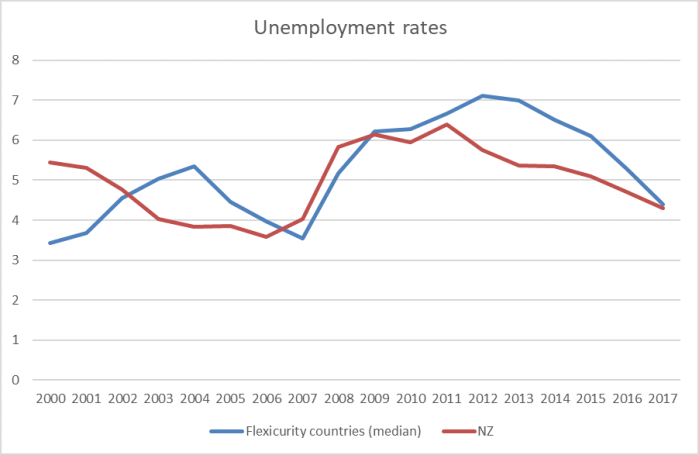

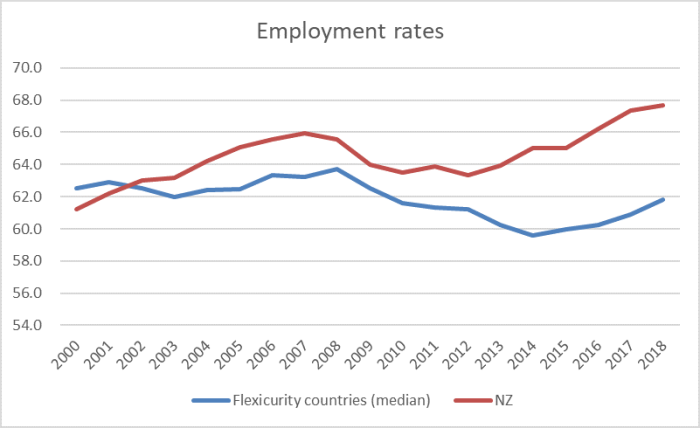

Or unemployment rates, not just a one year snapshot but a glance back over this century to date.

Most of the time, most years, New Zealand’s unemployment rate has been lower than that in the median flexicurity country. The differences aren’t always large, and aren’t even always same-signed, but it isn’t an obvious advert for the alternative model.

And what about employment rates?

Sweden has employment rates very similar to those in New Zealand, but taken together this group isn’t necessarily a great advert for an alternative income support model. Of course, in richer and more productive countries more people can afford to work less etc, so I’m certainly not suggesting the whole difference is down to the presence/absence of flexicurity. Perhaps there is a political “income distribution” case to be made – that’s one for political parties – but I’m struggling to see reasons why, evidence that, flexicurity offers potential labour market/productivity gains.

And to emphasise that flexicurity in these countries is just one component of a radically different approach to the role/size of government, here is a chart showing government spending.

The Commission even concedes (page 60) that materially higher income replacement rates when people become unemployed seems to be associated (in a cross-country relationship) with higher rates of (long-term) unemployment. As they note, it isn’t an ironclad relationship – there is always a lot of other stuff going on, which needs much more careful analysis to distinguish. But why they would jeopardise one of the more impressive economic achievements of New Zealand this century (low averages rates of unemployment, especially long-term unemployment) isn’t clear.

Much of it comes down to this alleged “attitudes to technology” issue, even though the Commission makes no attempt at all to show that fears about technology or job displacement is somehow a major factor – a factor at all for that matter – in low rates of business investment in New Zealand.

They begin one section late in the report this way

So even though the Commission itself has concluded (reasonably, or so it appears to me) that “fears of mass job losses from automation [are] unsubstantiated” one public opinion poll is enough to suggest there is some widespread systematic structural problem.

One might well wonder whether (a) it was not ever thus (except perhaps in the hyper full-employment period of the 1950s and 60s, and (b) whether those fears are not being fed by people like the Minister of Finance. Without evidence that any such fears are (a) much greater than usual, (b) causally connected to weak business investment in technology, and (perhaps) (c) evidence that such fears are lower in the flexicurity countries, it isn’t a great basis for proposing far-reaching policy change.

Following on from that extract we get this

Bredgaard and Daemmrich (2012, p. 2) described the Danish “flexicurity” system (Box 3.2) as a strategy for “economic competitiveness and sustainable national prosperity”.

Firms in Denmark gain competitive advantages from a mobile labour force and government funding of public services and infrastructure, while workers benefit from domestic employment opportunities and continuing training.

Well, perhaps, but I”m sure one can find champions for any country’s appraoch, but where is the systematic cross-country evidence, including relative to New Zealand (a country with lower average unemployment rates, lower long-term unemployment, higher employment).

And then there is this

But, as already noted, New Zealand not only has fewer job security protections than France – the bad example cited here – but fewer than those in Denmark, Netherlands, and Sweden. And one might remind the Commission that correlation is not causation, especially when it isn’t supported by any independent argumentation to make the case that (a) flexicurity produces these poll results, and (b) more importantly, flexicurity increases the rate of uptake of new technologies across economies as a whole. The Commission offers nothing on either point.

One could go on. The Commission notes that one “could” introduce “portable redundancy accounts” as, apparently they do in Austria. But makes no real case for doing so, and never seems to engage with (for example) the tax inefficiency (to the individual) of having various pots of money tied up in various places, all while (typically) having a mortage on the other side of the balance sheet. They toy with ideas of mandatory redundancy, but again without any attempt to demonstrate a connection to productivity or business investment. They worry about the ability of people who lose their jobs to service a mortgage, but never seem to adequately connect that concern to the fact that if there is a system that generates little long-term unemployment, most people are usually relatively readily able to find new jobs, and can self-insure (both formally, through mortgage protection insurance, and informally – it isn’t common for both members of a couple to lose their jobs at once). Mortgages in New Zealand are, of course, highly burdensome, but that is a reason to fix land supply and get the price of houses down, not to greatly enhance the welfare system.

Changing tack, I was also interested that the Commission did not touch on three other dimensions that might seem relevant to discussions around the sorts of schemes they propose:

- the fiscal automatic stabilisers in New Zealand tend to be quite muted. That reflects the twin facts that our tax system isn’t highly progressive and that our unemployment benefit system is modest and pays a flat rate. What the Commission proposes would strengthen the automatic stabilisers, but at the price of increasing the cyclical amplitude of cycles in the government’s budget balance. There are pros and cons to such a change, but they didn’t seem to be mentioned at all,

- the Commission rather overdoes the point about social insurance and how different New Zealand and Australia are to the rest of the world, but there is one important dimension they didn’t touch on. In other countries, the social security systems are typically partly funded by social security taxes on wages. That means tax rates on wages are typically higher than those on capital income. This is a relatively attractive feature, given that business investment (especially foreign investment) tends to be quite sensitive to expected after-tax returns (and people like Andrew Coleman and me have been making this point for years). Even if we did not increase welfare payments to the unemployed there would be a good case to lower income tax rates and raise the lost revenue through a social security tax on labour incomes. This wasn’t a dimension the Commission touched on and while, considered politically, that might not be surprising, it is quite a gap analytically.

In sum, there is no sign that the current Productivity Commissioners have any sort of robust defensible model for thinking about New Zealand’s long-running productivity failures. In particular, they show no sign of having thought hard about why firms operating here – and who might operate here – have proved so reluctant to invest more heavily over long periods of time. There is no evidence offered that excessive rigidity in the labour market, or fears of workers, is any part of the issue at all.

And yet they jump to champion quite radical changes in our welfare system, even including near the end of the report a folksy politicised cartoon

The economic case just is not made. Sure, it would be great to have a highly productive economy, but the Commission simply has not made a serious effort to demonstrate any sort of causal connection between their (apparent) personal political preferences around unemployment benefits/social insurance and any sort of plausible path to much better productivity outcomes in New Zealand. (And here one might note that places like France and Belgium – with quite restrictive labour laws, much more so than the flexicurity countries – have similarly high average rates of labour productivity.)

If they want to champion such a model – and reasonable people can debate the merits of some aspects of it in its own right – there is an election next year. Perhaps the Commissioners might consider standing for Parliament instead of using taxpayer resources to champion a different answer to inherently political questions.

The OECD is full of pinkos.

Gee i missed that.

what is the evidence for that claim?

Talking about climate change does not count. It is not a ‘left’ policy. It is supported across the board except for the ‘mad’ right who although very noisy are small in numbers and but very large in conspricies.

LikeLike

Actually, on the OECD point a few years ago I put to a v senior OECD official (then about to retire) that the OECD could reasonably be seen as a technocratic wing of European social democracy, and he smiled, blushed, and said he wasn’t going to disagree. (I’m not suggesting they are Jeremy Corbyn).

Re the climate change report, my point wasn’t about addressing the issue etc – they were responding to a govt request – but to the cheerleading nature of the resulting report, minimising costs of adjustment, misrepresenting some papers on particular interventions, and playing out possible (net) economic gains from adjustment. My concern wasn’t the specific recs mostly, but that it wasn’t a piece of sober dispassionate analysis.

LikeLike

Thanks for that. but we need evidence not opinions.

Have the OECD advocated ‘left leaning ‘programs . If they have I have missed them. It may well be it occurs when they report on you Kiwis.

LikeLike

Since mine was a passing comment on this occasion, not central to my post, I’m not going to spend lots of time trying to document the point, altho my impression over years engaging with the OECD and its material (incl their analysis and recs for NZ) and the long experience of my interlocutor isn’t irrelevant (to a commentary of this sort).

But to go on a little, I wouldn’t even have thought my comment was particularly controversial. They tend to reflect the consensus of economists, esp European ones, and that is much more “smart active govt” than, say, it was 30 years ago when I first dealt with the OECD. It doesn’t mean the OECD is opposed to markets, or harnessing them, but it tends to reflects its geography – northern Europe has pretty big govt (even if sometimes quite good regulatory systems. On issues of relevance to NZ i’d say the lean has been fairly Blairite.

LikeLike

No problems so it is merely your opinion over time.

Goodo

LikeLike

The largest problem is the comparative is done in US dollars. NZ and many countries do have a significant variability against the USD from one year to the next which does affect the compararives between nations.

LikeLike

make that conspiracies

LikeLike

People can already draw down their Kiwisaver accounts in cases of hardship like unemployment.

LikeLike

Which is a point the report notes, but still seems to want to have “new stuff” to offer.

LikeLike

Most I suspect would not want to go to the administrative trouble of that kind of draw down – and perhaps even more importantly, if they are prudent individuals, they know they will need that in retirement.

Hence, in the absence of a public scheme of income security (normally funded via tax paid on wages, such as in the US social security scheme) covering temporary periods of unemployment – what most NZers do who find themselves in this position, is take the first available job (or two, as many opt for more than one part time job). And many of these readily available jobs are those with low productivity – hence adding to our poor stats in that regard.

If one has the benefit/security of time in order to make a good-fit/choice regarding new/alternate employment after no-fault dismissal/redundancy – then I do believe our productivity statistics would improve. I think it is this best choice in re-employment that simply is not available in our present labour market settings.

LikeLike

Agree, this is a key issue with our current welfare system – it pushes immediate employment over waiting on a benefit for a more relevant job (relevant to skills, qualifications and experience).

LikeLike

I agree the unemployment benefit maybe shouldn’t have a stand down period so people aren’t so rushed into a new job and are more likely to take short term jobs than do nothing – but not convinced anything more substantial than that would have a material benefit.

They are plenty of other actions that could be taken to improve productivity – like lowering the company tax rate and top tax rate on investment income (interest and dividends) and marginal income tax rate for middle incomes, while maybe putting in a new higher tax rate on salary and wages over around $120,000.

LikeLike

I’m ambivalent on the first point, and even more generally on how generously we treat people who lose jobs at least in the first month or two unemployed, but (a) the more generous we are, the less people will bargain for redundancy pay provisions, and (b) it is mostly an “income redistribution” question, not a productivity one.

More generally, it is worth remembering that most job changes, incl most transitions to new firms/industries, don’t happen as a result of involuntary job loss (the focus of discussions about unemployment benefits) but from voluntary job changes and, to a lesser extent, new entrants/re-entrants to the labour force. (If it were otherwise, places like France would not have the globally competitive modern companies they actually have.)

LikeLike

Agree on the need for improved redundancy provisions. From what I’ve read of the Denmark flexicurity policy – union strength through favourable laws in respect of bargaining are one of the ‘three-legs’ of the flexicurity system.

We are way behind on those kind of non-monetary employment benefits being part of our labour market workings. Our unions are still pushing for living wages in the main.

LikeLike

Katherine, highly productive jobs demand a significantly higher skills. Consultancy, fund management type jobs are highly productive. Low skilled jobs in automated factories can also be highly productive. Can you imagine the productivity in a fully automated factory which requires only the human cleaner to ensure dust is cleaned up on the robots that drive the factory.

LikeLike

It would be good for nottrampis to follow their advice and talk facts not opinions. However, your post encouraged me to look at the composition of the board and management team of the Productivity Commission – from their published resumes it would appear their individual and collective experience is policy and government – arguably one person has hired others for their consultancy (in public policy). No one in that organisation has any experience of business or commerce from the sharp end as either an employer or employee.

LikeLiked by 1 person

okay mate you show some facts that show the OECD are a bunch of pinkos please.

Michael has clarified in saying it was his opinion.

LikeLike

I’ve always held the OECD reports in high regard. During the neoliberal era, they were very neoliberal in their analyses and recommendations (as they needed to address they many ills of largely bloated and over-regulated, protectionist states).

We have now emerged from that era, and in many OECD states, they transitioned to being under-regulated and hence, suffering the effects of over-indebtedness and stagnation.

If social democratic states have managed the neoliberal transition better (i.e., higher standards of living, higher levels of productivity), it does make sense for the OECD to alter its analyses and recommendations accordingly.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting that the commission doesn’t consider a never ending supply of cheap immigrant labour as a possible reason for companies not to bother investing to make existing staff more productive. Ignoring this is neither left or right leaning as both sides treat it as an essential part of our future.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, that is telling, esp as under previous management the Commission published a “narrative of our productivity problems” that did tend to recognise that high rates of immigration hadn’t necessarily been an unalloyed economic gain to NZers.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Australian Productivity Commission 2006 report into Australian Immigration found all the economic benefits from immigration were captured by the immigrants themselves with no benefit to the locals

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gissie, perhaps most of the growth in our economy is mostly in the hospitality, aged care and the health sector. Darpa will pay you $2 million dollars if your hospitality/aged care/healthcare robot can open a round door handle, step through it, walk up the steps, get past the furniture and avoid the pencils and ball bearings on the floor. Yes $2million for a single robot. My 10 year old can do all that for free.

Perhaps that is why we still need migrant labour?

LikeLiked by 1 person

To be fair to Michael, I have tried to take in his articles without any leaning right or left.

Not directly linked to this contribution but Gwynne Dyer in the Herald yesterday

https://www.nzherald.co.nz/opinion/news/article.cfm?c_id=466&objectid=12286501 about changes in advanced country societies.

I will just summarise by quoting the last section of Dyer’s article

The one common denominator that might explain it is the growing disparity of wealth – the gulf between the rich and the rest – in practically every democratic country.

Since the 1970s, income growth for households on the middle and lower rungs of the ladder has slowed sharply in almost every country, while incomes at the top have continued to grow strongly. The concentration of income at the very top is now at a level last seen 90 years ago during the “Roaring Twenties” – just before the Great Depression.

We could fix this by politics, if we can get past the tribalisation. Or we could “fix” it by wars, the way we did last time.

LikeLike

There is a gulf between the very very rich and the rest of us but that was true when the UK and almost every country except NZ had an aristocracy. What used to be a gulf was the gap between the working class and the middle class; that has changed with the gap narrowing. There still is a working class but thinking of a specific working class family they go snow boarding in winter, fishing at weekends, take foreign holidays, upgrade their cars regularly and maybe have bigger TV screens.

In the past you had a poor blue collar class and a fairly well off white collar class; this has been replaced by a poor class with children and comfortably well off childless yuppies. The fact that the latter have massive student and mortgage debt doesn’t stop them enjoying life.

[Another plug for a generous universal child benefit – it is not the size of our welfare system but how it is spent that is the trouble].

LikeLike

There may be a gulf in dollars but the difference in the types of goods to buy is only marginally different. I went shopping for shoes yesterday. I could barely see the difference between a Warehouse $28 pair of shoes, compared with a Nike $250 pair and a Prada $2,000 pair except for the pattern design and the label. Similar with the belts and the T shirts.

LikeLike

ICYMI – social democracy at work

Last month Deputy Prime Minister Winston Peters said up to 31 percent of migrants who sponsored parents into NZ subsequently left the country, leaving the parents behind, and leaving taxpayers to pick up the bill for parents

https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/political/403779/cabinet-considered-deporting-parents-of-departing-immigrants-documents

LikeLike

supporting high levels of immigration is left wing?

you need to tell our government that

LikeLiked by 1 person

Of course it isn’t, it is one of the few subjects both left and right support. Either because they believe in it, or neither want to slow it down and potentially set of a major downturn as our economy adjusts.

LikeLike

There is a 10 year stand down period for any migrant parents accessing social welfare. The largest increases in Universal Super has been due to Winston Peters expanding the entitlements to the Pacific Islands where they need not even have set foot in NZ ever and make it a NZ taxpayer funded retirement.

LikeLike

If and only if elderly people arrived, with medical insurance covering the rest of their life, a fully inflation proofed pension equivalent to our superannuation and contributed their share of the existing national infrastructure (about $500,000) then I reckon they would benefit NZ just as much as tourists do but without the carbon emissions. Think of them as valuable export earnings. I’d say that was a right wing capitalist view but it still seems a good idea to me. If you live in an unpredictable country and you are old enough to have seen what happened to wealthy old people living on savings in Zimbabwe, Venezuela, Syria, Lebanon, etc you might be attracted to a good old boring country with no snakes. Obviously attractive to Chinese but also Bengalis, some Indians, many Syrians – we ought to be auctioning permanent residency giving extra point counts for age. But non-working Visas – our low paid need no more competition.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Utopia, you are standing in it!.

LikeLike

These guys get things the wrong way around. Most of these Nordic have successful businesses, paying taxes, allowing the state to provide nice things. It is not because they have nice things that they have successful businesses.

They haven’t discussed Germany in this, which is occasionally lumped with the Scandanavians and Dutch as the classic social democractic, successful country. I offer a few comments on this, based on my anecdotal experiences… they have here similar programmes – from an employee’s income they deduct income tax, solidarity tax (if you are in old west Germany – money earmarked for old east german states), church tax (if you declare to your local townhall you are Catholic or Lutheran), then various ïnsurances” – retirement, health, aged care, and social (unemployment). These are still really taxes – the social, retirement and aged care go to government run organisations. The health goes to nominated insurers who are nominally independent but not profit making companies.

If you get made unemployed you get 60% of normal pay or 67% with children, but it depends how long in post you are. Likewise redundancy pay, this is calculated based on years of employment with an uplift for years above 50 or 55. All quite generous, but the incentives it provides are disastrous – Germany just hasn’t recognized this because things have gone quite well for the past twenty or so years. Contrary to the report, people here are incented not to change jobs – labour market “protections” mean employers are very cagey about taking on new employees. Once in a role, it is not worth changing if the new position is only marginally better – there is a six month probation period – so risky for the employee, and once in the new post various benefits start to accrue which are reset if you change (and longer in post you become harder and more expensive to fire). In New Zealand none of this is present – jobs are easy to lose but easy to get, and there is no benefit for staying if you don’t like it (beyond the probation period).

Having worked with people here now, I get the impression there are a lot of people who aren’t particularly happy or committed to their job, but don’t want to risk any change – just run down the clock to retirement. If you rent a home here (60% do) and you have been there for a while, rent controls will likely mean you pay well below market rents for your house. If you decide to move for a job, your next home could be a big jump up in rent. Those two things are to my mind, disastrous for productivity (and the rental market – I know some people who have kept rentals going, in unoccupied flats, just because it has become so cheap its worth having the old apartment in case you decide to move back a few years later). On top of it all, it breeds a cultural mindset of risk aversion, complacency, which is exactly what an economy doesn’t need.

I can’t speak for the flexicurity states but my impression is they are similar. For all the purported “protections” they end up being a gilded cage. The only positive I see in this is that the employee’s pay slip shows where the various shares of employee’s taxes wind up. This transparency is helpful for democratic debate, if you recognize them properly as taxes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting insights in comparison – thanks.

LikeLike

I have argued persistently that these countries have large automated factories or significant mining resources or trillion dollar computerised fund managers that give them that productivity edge. We have shut down most of our factories, we refuse to mine and we do not have large funds to manage. We used to have EXGO grants that subsidises exported products and duties that protected our factories and industries but it also forced up inflation where our protected industries just increased prices whenever they needed a profit.

Most of our subsidies are now in culling cows or disease control or DSIR research supporting the primary industries.

Perhaps NZ is just ahead of the curve rather than behind the curve as we have allowed much more market freedom as to what the future holds relegated to mainly service industries like hospitality, aged care and health care services.

LikeLike

If we taxed the free capital gains and also taxed the externalities then perhaps we could afford to reduce the tax on capital and encourage some more capital intensive industries in NZ.

LikeLike

If you are going to tax capital then how do you encourage more capital intensive industries? The higher the tax is usually intended to discourage rather than encourage?

LikeLike

Also based on the median wealth per adult (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_wealth_per_adult) NZ is not doing too badly at all (rank 7th)

LikeLike

Artificially high house prices will do that to a country….

LikeLike

When a country can afford to do things like not allow offshore mining exploration when it owns one of the largest maritime ocean boundaries in the world or refuse to build wharf extensions to allow mega cruise ships to dock and spend in your cities or turn down development because it may interfere with fish and bird habitats, that’s the bevaviour of a very wealthy people. Or the alternative is just plain stupidity?

LikeLike

Artificially high house prices will do that to a country, sadly…

LikeLike

I am unsure on what is wrong with social democracy.

You could have neo-liberal policies allied to a social welfare state. This would mean looking after the poor and downtrodden whilst the econmy is growing. This is almost biblical.Actually it is not almost it is..

LikeLike

My main point in the post was that (a) that is a political call not a technocratic one, so let political parties make/argue that case, and (b) to the extent that the Prod Comm people tried to make a technocratic/economic case, around links to productivity/tech transitions their case seemed threadbare.

My personal view is that I favour pretty (more) generous treatment of people who really can’t help themselves (eg long-term disabled). Around the working age population, the arguments prob need to be specific issue by specific issue.

LikeLike

Thanks Mike,

It seems we are in agreement I think

LikeLike