The New Zealand Initiative last night released the results of the general knowledge quiz conducted for them by a polling company. It is a good way to get media coverage – and I’m as much a data junkie as anyone.

The real point of the exercise was as a prop in making the case for a greater emphasis on a knowledge-based education system rather than the current skills-based focus. I’ve told the story before about going to a meeting for parents of new entrants at the local school a decade or so ago, where the Principal – a fairly vocal figure in the world of educational politics – told us that they weren’t going to teach our children facts, because they would soon be outdated. Fortunately, when I tried the NZI quiz on my now 16 year old he got 12/13, despite the New Zealand education system.

The headline, of course, was that this sample of New Zealand resident adults wasn’t particularly good at answering the NZI’s questions, many of which look pretty simple or basic (at least to the sort of people who read either NZI material or blogs like this). Across 13 questions – of which five were either yes/no or limited multi-choice questions – the median proportion of respondents answering correctly was 53 per cent (that was the question about how long it took earth to orbit the sun). And although much of this post will be a sceptical take on the significance of the survey, even I will concede to being surprised that only 32 per cent of respondents could correctly name the year the Treaty of Waitangi was first signed. I doubt the Treaty was ever mentioned in my whole schooling, but it is (repeatedly) today, and yet the worst results were for the 18-30 age group (where only 23 per cent got the answer right).

The NZI released the detailed breakdown of the responses: we have all the answers by age, sex, metro/provincial/rural, by “deprivation decile”, and by whether schooling had taken place in New Zealand or abroad. Curiously, there was no ethnic breakdown.

One thing I haven’t seen covered elsewhere – or, of course, in the NZI write-up – is the systematic male/female differences. For quite a few questions there is almost no difference between male and female responses, but for seven of the questions the differences looked to be material and in only one of them did women outperform men.

| Per cent correct | ||||||

| Female | Male | |||||

| How long does it take for earth to go round sun | 44 | 62 | ||||

| What year was the Treaty first signed | 29 | 35 | ||||

| Native Land Court purpose | 32 | 36 | ||||

| Correct use of “their/there” | 83 | 77 | ||||

| Derive distance travelled from speed and time | 41 | 56 | ||||

| Name seven continents | 39 | 50 | ||||

| Compound interest question 1 | 49 | 66 | ||||

| (Harder) compound interest question | 23 | 46 | ||||

I’m not sure what to make of those differences, but since I work on the assumption that women are just as intelligent as men, perhaps it suggests something about how the questions are framed, or…..? (Note that the NZI person responsible for this project is a woman.)

There were some differences between those schooled here and those schooled abroad. Knowledge of when the Treaty was signed and about the Native Land Court was less good among those schooled abroad, while the migrants were more likely to be able to name all seven continents and to be able to answer correctly the harder compound interest question.

People from poorer areas typically knew (or could work out) fewer correct answers, but by age the answers were a bit mixed. The only one surprised me was (see above) the Treaty response where the older people were the more likely they were to know the correct answer. Of the other questions, there were quite a few where younger people now knew more the older people now but where you would have to wonder whether those same young people will know as much 50 years hence. There are plenty of details I learned at school that I’ve either forgotten or are now rather hazy – while other, mostly unused, things stay locked in the brain and are never asked about in surveys or quizzes (here I’m thinking of the quadratic formula as an example).

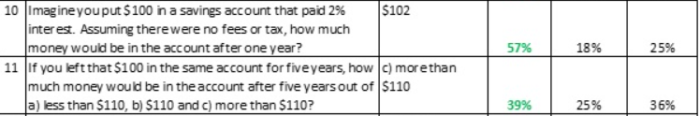

In general, I am sympathetic to the Initiative’s cause, for a greater and more systematic emphasis on knowledge in our schools. But I am left quite sceptical about the value of surveys like this, except as a way of getting media coverage, and perhaps feeding the self-esteem of a certain class of well-educated and knowledgeable adults. Most people actually do manage to get through life tolerably well and the world is richer and more materially prosperous than ever (as the Initiative would often rightly point out, in pushing back against other nanny-state proposals) and I’m left wondering why, if at all, I should be bothered if people can’t answer particularly well over the phone – perhaps caught while they are cooking dinner or doing the ironing – compound interest questions (green are the correct answers).

Most people don’t leave a fixed amount in an account for five years and reinvest all the proceeds, there are fees and taxes, interest rates change over time, and actually if you invest for five years at 2 per cent interest per annum and spend none of it and pay not fees/taxes, you’ll end up with with $110.41 which most people would round to $110.

But this isn’t enough for the Initiative

Our poor grasp of maths is also concerning. Basic arithmetic is critical for personal financial literacy. It is difficult to understand mortgages, savings and investments without the mathematical keys. But knowledge of maths goes beyond finance to everyday life. Try renovating your house, baking a cake or calculating medicine doses without basic maths. It is true that the 20th century provided us with calculators, but if you do not understand maths you are poorly placed to check your electronic answer.

And yet people do get on. We don’t have some mortgage default crisis, we have pretty low rates of elderly poverty, nothing about finance (at a personal or national level) seems to be spinning out of control. And while the main thing for which I now use the formula for the area of a circle is to adjust recipes to the desired size of cake tin, somehow I expect most homemakers get on just fine without it. (I raised some doubts about the value of “financial literacy” programmes in a post here.)

And is it particularly useful to know the antibiotics are about bacteria not viruses? I did know that, but it isn’t particularly useful to me. Instead, when I go to the doctor I typically take his advice, and when he prescribes something I try to follow the prescribed instructions. It probably matters rather more – in term of keeping antibiotics useful – that (a) doctors don’t over-prescribe and (b) patients follow instructions. Or so I’ve been told, and I’ll operate of those rules of thumbs (especially the latter) for now.

Which brings me to the paper Briar Lipson has written using the quiz results as a prop for calls for reform of the education system. It is a curious piece in many ways, perhaps especially coming from a think-tank which is generally regarded as fairly libertarian in its inclinations. Their chief economist Eric Crampton often cites approvingly the stimulating work of GMU economist Bryan Caplan, one of whose books was devoted to casting considerably doubt on the value of much of education (facts-based or not) in building skills – as distinct from certifying a work ethic, conformity, and basic intelligence. A screening and sorting mechanism more than anything (as I’m sure knowledgeable parents recognise when they hold conversations with smart teenagers and have to distinguish between richer and deeper answers and those that will jump through the right hoops to secure NCEA credits).

I was a little amused to note her claim that

As a bicultural nation with a colonial past whose ongoing legacy is playing out in our troubling national statistics, it will never be easy to answer these questions.

It could have been written by the Maori Party, but it was actually written by someone who isn’t a New Zealander and who appears to have been in the country for not much more than two years. It doesn’t invalidate her expertise on education itself, but that ‘our’ is surely just a bit of a stretch?

There is a quite of this black armband approach. For example, we are told that “inequality…threatens wellbeing and prosperity”, which is a rather different (questionable) tone than we typically get from the Initiative. I presume the audience for this is the Labour Party, but even so……facts, knowledge etc. It carries over to the caricature of history.

For most of history, only the wealthiest had the time and resources to pursue disciplinary knowledge. For the rest of society, knowledge beyond daily experience was an unaffordable luxury. Accordingly, the ability to read and write was limited to the elite: noblemen (yes, only men) and clergymen (again, men). If you toiled for a living, your horizons were narrow.

Yes, poverty was quite limiting, but all that “only men” stuff would surely have come as quite a surprise to Hildegard of Bingen, Catherine of Siena, Anna Comnena, Teresa of Avila as just four fairly prominent examples. Lipson’s treatment of history here is the sort of thing that makes people like me – who fairly strong support, in principle, the idea of more systematic history in our schools – rather nervous of what it will turn into in practice.

There is more dodgy – or at least highly arguable – history: thus on her telling it is the Enlightenment that brought us literacy. Pretty sure it had almost nothing to do with the first New Zealand schools.

I totally agree with Lipson here

Whether you are building a house, playing the violin or deciding to immunise your child, knowledge is essential, because there is not a generic skill of problem-solving or critical thinking. As anyone who has lifted the bonnet of a broken-down car knows, problem-solving skills do not exist in the abstract.

And yet she starts her note with the observation that

For most of history, only the wealthiest in society had the time and resources to pursue disciplinary knowledge. For everyone else, knowledge beyond daily experience was an unaffordable luxury.

And yet I don’t need to know how the engine in my car works. Most knowledge most people actually use day to day is really rather specific.

A few other questionable snippets

To converse meaningfully with each other, and evaluate the performance of our political leaders, we need to have knowledge that takes us beyond our daily lives.

Set aside the evaluation of political leaders, but does Lipson really suppose that the vast mass of people – who couldn’t answer her quiz questions correctly – somehow don’t manage meaningful interactions and conversations? The revealed evidence seems to be against her on this count. It won’t be Wellington elite dinner table conversations, but are the relations and interactions – the thick web of connections that makes up most individuals’ place in society – any less effective or profound?

We get another of those “Wellington elite” type of perspectives in this comment

To grow into active, engaged citizens who can think critically about the wider world, children need to know about language, science, maths and culture (including but not only their own). However, only 44% of New Zealand adults can name the seven continents, let alone locate Afghanistan or South Korea on a map – countries where our defence force has personnel in the field. Issues like national defence, along with migration and trade, are all critical to New Zealand’s role in the world. But how can we expect voting-age adults to engage with New Zealand’s geopolitical challenges – and how our nation should respond to them – if they do not even know where in the world the challenges lie?

I’m simply not bothered if people can’t find Afghanistan on a map. One could mount a – slightly flippant perhaps – argument that it would be better if fewer people could, because it would probably have meant fewer western armies and associated headlines there, and from there, over the last 18 years. More importantly, it is delusional to suppose that a school education – no matter how good – is going to equip people for debates about the nature, and source, of geopolitical challenge or (to take another topic close to this blog’s heart) the pros and cons of a large scale immigration programme to a remote corner of the earth.

Lipson goes on

We might debate whether these skills are any more important this century than they were in the past; either way, we must agree it would be difficult to think critically about the Hong Kong riots without knowing something about Hong Kong’s history and geography. It would be equally difficult to evaluate policies on use of plastic without a basic knowledge of biochemistry and economics.

I think I am safe in saying that, for better or worse, most New Zealanders have little interest in the Hong Kong riots and although, in some sense, I personally might wish it were otherwise, it isn’t really clear why that is a bad thing. (As it is our government tries to pretend to having little interest). And – while perhaps I’m missing something crucial – I’m not clear quite what Hong Kong’s geography (does she mean a tight city-state, or located next to China?) really has to do with it. Personally, when I think about Hong Kong I worry most about the fate – persecution and repression – that awaits my fellow Christians under mainland rule, but I wouldn’t really expect that concern to be universal.

(As for plastics, personally I found the values of choices, self-responsibility, and ensuring I – and my kids – don’t litter, more relevant to my views on plastics policy than my knowledge of biochemistry – next to none – or economics.)

You can read Lipson’s piece for yourself (and it is an important issue). I guess my bottom-line concern is that she has grossly over-reached. Across her scattergun range of examples, she encompasses a range of topics/knowledge that few (if any) are likely to master, or have much interest in doing so – even building on decades of adult acquisition of knowledge, not 11 or 12 years of schooling. I’m all for getting a better balance between on the one hand concrete fact-based knowledge and sketch narratives of things like our history and that of societies to which we are heirs (the narratives, if pushed, matter more than the dates) and on the other the research, reasoning and problem solving skills the current New Zealand system tends to emphasise.

But the modern world relies on a considerable degree of specialisation – indeed it is integral to our prosperity – and that is as true of public life, political and social choices, as anywhere else. I’m not promoting, let alone defending, any sort of “rule of experts” (and I’m pleased to see that here the Initiative is not heading off after things like epistocracy) but hardly anyone votes based on a comprehensive review of in-depth party policies across the board. Even on a specific issue like climate change, few of us (really can) vote that way – I might claim some expertise in the economics, but not in the science, and there are very few people who combine both. And values count a great deal, and yet nothing in the NZI quiz – and almost nothing in Lipson’s note – was about forming people in the values that make for a successful, stable, and prosperous society.

In truth, we take our lead from others – rules, precedents, examples, people who enunciate values that relate to our own – and leave much of the detail to others. It is unavoidably so – and I say this as someone who has more time, and probably more capacity, to dig into lots of issues at a fairly technical level. We rely on others in almost all areas of life, and one could at least mount an argument that learning how to think about who and what one might trust is much more important than, say, learning the details of the Danzig question, Hong Kong’s geography, the biochemistry of plastics, or the precise reason for the establishment of the Native Land Court. As Lipson puts it in her title, ignorance is not (generally) bliss and yet – on the other hand – a little learning can, in Alexander Pope’s words, be a dangerous thing.

I could go on, but won’t. But I’ll end where Lipson starts. In the entire body of her seven page text there is nothing about forming people in the values that a society should live by. I suspect she is probably an adherent of some fact/value distinction (Winston Churchill was a real person, regardless of you views of the nature of good), and clearly there is something to that split, and yet if her goal is a functioning cohesive effective society and polity values formation is likely to be at least as important as specific factual knowledge. It isn’t enough to say that home is the place for that, since we all know that nature abhors a vacuum and that what our schools teach is heavily value-laden, by default if not always by design. Lipson begins with a quote, which appears to be from an Australian teacher

It is not the natural state of humans to live in relatively free, democratic societies that tolerate difference. Because of this, we need education to protect and preserve these societies; to transmit important cultural knowledge from one generation to the next, and value our civilisation.

I’m not sure those two sentences really relate to each other, but if you take seriously the second sentence – as I do – you’d find it bearing almost no relation to either the facts quiz that got NZI its media coverage, or to the thrust of Lipson’s appeal to teach facts. It is about a cohesive narrative that recognises what is good and what is not, what is great (eg art, music, literature, ideas) and what is not, and takes pride in what has been built. And that requires an ethos, a mindset, that has made sense of life and the world. You might call it a worldview or a religion. But it is very different from knowing the names and dates of the kings and queens, the names and dates of all our Prime Ministers (useful as, in some sense, those latter might be). The (narrow) facts just don’t get you far. I’d rather people “knew” that Communism has been, and is, a great evil than that, say, they knew the geography of Hong Kong or the biochemistry of plastic

“”Our poor grasp of maths””. There is a need to separate arithmatic and maths. Arithmatic is to spelling what maths is to writing. Every child ought to be drilled into basic numeracy and then taught how to use a calculator to make it easier. Then maths starts with an introduction to algebra. I have read that proficiency in your first year of Algebra is a better prediction of success in working life that proficiency in any other subject (presumably because of the use of abstraction).

Of course values matter more than knowledge. But they are taught at home and at pre-school. My almost three year old granddaughter is a continuing lesson to me. A recent study discovered 75% of conflicts between pre-schoolers are arguments about ownership of toys – so economics comes first, even before the forming of coherent sentences.

Ms Lipson says “” we need education to protect and preserve these societies; to transmit important cultural knowledge “”. True for pre-school but the current controversy about Indian arranged marriages (so similar to the British Raj with officers returning to England to search for a wife) means a modern school would have to simultaneously teach Kiwi girls that their body is their own and to enjoy sex on their own terms while teaching young Indian boys to esteem virginity. Values are far too dangerously divisive for modern schools; best to be left to family and church.

LikeLike

I think there is an important distinction between techniques and things beyond that. One can teach kids to write, to read, to count, even to do algebra – or how to fix a car, cut hair, cook a good meal – without the insertion of more values/morality than might be implied by thinking universal compulsory schooling is a good thing. One can teach lists of kings and queens, dates of principal acts of Parliament, the principal rivers and mountain ranges of each continent without much more intrusion of values/morality. One might teach the skils that in time lead one to be able to do diagnostic medicine, or to use econometrics similarly.

But a great deal of school is overlaid with values/morality, and that is inescapable – at least unless we default back to only facts/techniques. That is obviously true of “sex education” – the example you cite, which conceivably could be taken of schools altogether- but it is very obviously true of history: it is a story, which involves selection, emphases, narratives. I suspect I and Morgan Godfery would teach NZ history, even since 1800, very very differently, and it isn’t enough to say “so present both”, when we are talking about the exposure of young kids to a few hours of history (as distinct from advanced university study). Same goes for almost anything around environment/climate change, quite a bit of even school level economics (because presuppositions/emphases of teachers matter a lot), let alone the championing of gay issues (which seems to pervade at least one of the schools my kids attend). Some of this stuff is over the line – teachers who openly champion their preferred political party – but much of it is inevitable, and an alignment between the values of home and school (and church for our wee minority) is probably something most parents want and society in general should value.

That leaves me favouring a proper voucher-based education system in which parents are fully funded and can send kids to a school that is consistent with their values/narrative. As that quote implies, much of raising kids is handing on to them the wisdom of the ages.

(More generally, I’m of the view that stable democracies can’t survive without a fair degree of commonaility og values/morality. That may look to run against my line about funding everyone to pursue their own faith/values, but the latter is to recognise really big differences exist; the former is to doubt how sustainable this is in the longer term.)

LikeLike

Naill Ferguson has a YouTube video about the death of history by which he means the broad sweep of history. Certainly current ignorance of the basic facts of history is astonishing and frightening; it allows demagogues to fool us with a biased and selective interpretation of the past.

Maybe a stable democracy is better able to survive a broader spectrum of belief/values/morality than a totalitarian regime.

My views are influenced by Taleb’s comment about Lebanon being multi-cultural for over a thousand years and when a dispute between different groups errupted his uncles told him “don’t worry the leaders will sort it out in a couple of months as the always have” and that was followed by eleven years of death and total destruction. That combined with the history of the Northern Ireland ‘troubles’ does make me far more apprehensive of efforts to make NZ multi-cultural than many of our academics and politicians.

So I will agree with you about a fair degree of commonality of values which I take to mean some effort to select and assimilate immigrants.

I would vote for a voucher based system of education although given the generally high standard of schools in NZ it would not be my priority. However with one condition – swap the history teachers – a lesson that took 400 years for Northern Ireland to learn.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think our economists could do with a lesson in maths.

I think it is mathematically incompetent to think that when NZ Household Cash Deposit savings equate to NZ Household House debt an increase in the OCR would result in a reduction in NZ overall consumption or a drop in the OCR would increase overall NZ consumption.

LikeLike

The Land Court question offers a PC answer unjustified by objective scrutiny of the actual Act.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I was happy enough to go with that answer because it clearly wasn’t the alternative (“set up to return land to Maori”). But yes one always has to be a bit careful once one gets to intent-type questions.

LikeLike

In fact the duties of the court include establishing valid ownership titles and shares for Maori individuals so it does return land to them.

LikeLike

“The Native Land Court was one of the key products of the 1865 Native Lands Act. It provided for the conversion of traditional communal landholdings into individual titles, making it easier for Pākehā to purchase Māori land.” nzhistory.govt.nz

LikeLike

Yes the Native Land Court question I thought showed more about current thinking on the subject i.e. ‘ALL Maori land was stolen’ than anything reasonable. As if Maori would have wanted the land they had sold back again (unless to resell it) the real answer should have been of course to make Maori land easier to buy and easier to sell-in fact to regulate it. I have had countless Maori tell me on Facebook that ALL Maori land was stolen-none was sold at all-in spite of the deeds of sale still existing. We are living in strange times I think! And made even stranger by a government funded but largely unregulated, separate Maori school system which will continue to produce huge distortions in our knowledge base.

LikeLike

Exactly. Whatever we think was the intent, I doubt it was so at the time.

LikeLike

It is certainly a lie that most land was stolen. Maori forget they actually sold most of their land for guns, western jewellery and trinkets. Back then land had no value. Even 30 years ago a Maori chap offered to sell me 140 acres of prime waterfront property in Lea just off the Goat Island reserves for $140k. Back then I thought that was expensive.

LikeLike

I think every school should teach cognitive behavioural therapy. Its especially relevant to those with a colonised ancestor in the family tree yet our political system endorses unhealthy ways of thinking.

On inequality being bad for us so is diversity where it adds distance to community bonds. NZI have no interest in anything that might slow migration though.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Older people know the Treaty was signed in 1840 because of a national film unit production One Hundred Crowded Years

This was shown to school children while Julie Zhu and Paul Spoonley inform us that there are Maori and Migrants.

LikeLike

The 5th question being “Which country was the first to grant all women the vote?””. Wikipedia disagrees with the published answer; from its entry for the history of the Pitcairn Islands “” Pitcairn became the first British colony in the Pacific and also the second country in the world, after Corsica under Pasquale Paoli in 1755, to give women the right to vote “”.

I know nothing about the history of Corsica in 1755 but I expect Pitcairn did actually give all women the vote whereas even to this day New Zealand has some restrictions to voting by women.

Quotes “” All women who were ‘British subjects’ and aged 21 and over, including Māori, were now eligible to vote (the nationhood requirement excluded some groups, such as Chinese women) “”.

“” The Electoral Act 1893 gave all adult women in New Zealand (with some exceptions, notably ‘aliens’ and inmates of prisons and asylums) the right to vote in the general election “”.

It is quite surprising how long it took the rest of the world to copy us; I doubt if Pitcairn or Corsica were ever inspirational examples.

LikeLike

Interesting. Pitcairn, of course, wouldn’t count as a country.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Why? Checking the dictionary: Country: “a nation with its own government, occupying a particular territory”. If Pitcairn had elections then it had some form of government however limited. It is/was clearly under the crown as a colony but pardon my ignorance of NZ history but was NZ a fully fledged country in 1893 with national anthem, flag, currency, armed forces, foreign policy?

LikeLike

Even today Pitcairn has less autonomy than nz had in 1893.

But check out the fascinating list in this, incl Victoria in the mid 18th century which accidentally legislated to allow women the vote, and repealed it a couple of years later (but not until after an election where women had voted).

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_women%27s_suffrage

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great link. I like the restriction to over 21 and literate. We should insist on voters knowing the date of the Treaty of Waitangi.

LikeLike

Most of the countries we know today in Asia, middle east and Africa was created by the British Empire.

LikeLike

Interesting paper on the de-regulation of the NZ education system in the 1990’s and its characteristics of a “voucher system”

Policy Experimentation and Impact Evaluation:

The Case of a Student Voucher System in New Zealand

DECEMBER 2017

Sholeh A. Maani

The University of Auckland and IZA

Click to access pp137.pdf

LikeLike

Thanks. Looks interesting in its own right, altho by no stretch of the imagination could that period really be called a voucher system. The choice was only within the state system and successful/popular schools were typically not able to expand or, say, takeover struggling or failing schools. It was a modest step forward at the time, but in terms of real choice may have been less important than the 1970s integrated schools model (which does provide some effective choice of ethos for some).

LikeLike

It’s also arguable whether Corsica was really a ‘country’ at the time – don’t think its breakaway from Genoa was widely recognised, if at all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And 14 years later Napoleon was born there. That may have made the concept of women’s sufferage unpopular for the 19th Century. Obviously I’ve some more reading to do.

LikeLike

There is enough for a whole conference in this post… what is a good education? The NZI creates a false dichotomy here – you either have fluffy skills based education or a rigid fact based one. Both are wrong and you can see exactly what wrongness results from the so-called fact based approach.

The question 13, on naming the continents, assumes there are continents. To my understanding this is considered by geographers and geologists as an anachronistic, incorrect term and has no official meaning. Europe and Asia are one landmass for instance – the distinction between them is man-made and arbitrary. A proper education would cover the fact of this terminology, and how conceptions of geography have changed over time, but it is wrong to assert this is a fact.

The answer to question 7 is, as other people have pointed out, politically inspired. The true purpose was to formalize land title for existing Maori owners. All manner of possibilities open up once so formalized (accessing finance against the title as collateral). Admittedly the outcomes of this may have been politically exploited by early colonial governments – but to present the answer as a fact is simply ludicrous and embarrassing when you imply ignorance of anyone who answered incorrectly.

Question 9, distance covered, is like question 13, one answer a teacher could give when teaching the sciences of motion, physics. It of course assumes a number of constants – the earth itself is moving during this time. Obviously we all know what they mean by the question, but proper education would teach that most superficial facts have layers of complexity and relativity to them.

Question 3 is also one where we can only say, to the current understanding based on the so far discovered fossil record, dinosaurs did not exist with modern humans (I am not an advocate for that idea btw). But again, proper education would teach children how we come to that view, and that it is always subject to review. If tomorrow a fossilized dinosaur is found fighting a fossilized man, we must reconsider it. Furthermore, it presupposes discrete time bound categories of dinosaur and man – proper education would teach about genus, species etc. but also about the limitations of these concepts.

All of the nuance and critical thinking needed to analyse those questions comes from proper education. Admittedly that is probably missing in today’s system (judging by Ms. Lipson’s own work).

Dismissing teaching skills is equally inane – aside from the fact reading, writing and arithmetic are skills, things like delivering speeches and presentations (rhetoric in classical education) are vitally important to develop critical thinking and enable the student to communicate his ideas (far more important to democratic life then memorising facts and figures). Presumably NZI wants us to be just like China – memorizing facts and regurgitating them out at end of year exams, so we can be unthinking automatons in the economy… fine, but I worked for several years in a Chinese company and observed that not one of my Chinese colleagues could deliver a structured, thoughtful and charismatic speech, training or seminar. They just have not learnt it.

LikeLike

In fairness, I think the NZEI/Principals’ Federation and the Ministry also tend towards an either/or – see the comment from a former Principal at our local school (and incoming head of the Principals’ Federation.

But, yes, Lipson didn’t do a great job of articulating a different model, which might be built around a shared framework of facts, overarching narratives (that select and highlight) without losing sight of the skills around writing, research, critical thinking, even rhetoric (some of those at suitable ages – research projects at age 6 tend to be a great deal of work, incl for teachers, while skipping over laying the foundations of systematic knowledge.

I’m ambivalent re names/dates. In many respects they are less important than making sense of, say, the flow of history, key interconnections etc, but they also do provide markers, points of reference, and even help the confidence of kids, who find themselves able to say “yes, I knew about him/her” or “yes, I knew the Treaty was signed in 1840” – I see a little of that even among my kids (two geeky and knowing huge numbers of facts, one – proudly – not but of course picking up more than they realise).

I think Lipson and the Initiative run into problems because NZI is really libertarian in orientation. That creates a tension: their own frame of reference is highly individualistic, and yet this report is about trying to lay down an approach for an entire compulsory state system. In a way, the NZEI/Principals’ Fed face similar issues – they are often embarrassed by our past and heritage and want to make the world new, but can’t directly confront a radicial alternative narrative, so they champion a model in which everyone does whatever they want. An well-rounded education really only makes sense within a culture/worldview – and hence my championing of vouchers.

Another issues NZI could usefully pick up is an absurd narrowing of focus to NZ. In 7th form history for example, the only real requirement for subject matter is that it has to relate to NZ. Probably they could manage WW2 topics under that rubric, but it would be hard fit many pre-1769 topics to that bill, without stretching it to the point of absurdity.

LikeLike

My grandson will start year 7 next year He is full of the curiousity of an eleven year old and his back ground knowledge of history is minimal. What ever history he is taught can only be a bare introduction so I have no issue if it is focused on NZ. In fact it would be my preference. History reflects the pre-occupations of the current society so knowing ‘how it was’ in your own country is a good starting point.

See todays letter to the Herald by Vivienne Wilson about the occupation and ownership of Ōwairaka. That could start a discussion about why Samuel Marsden was in NZ; how much was 160 pounds worth in 1835; what type of farming was practised and who were the customers; why did Maori tribes fight one another before the arrival of Europeans, what weapons did they use, why were tapu respected? It is all fascinating. Time I started reading about NZ history.

Of course if you mean 7th form as year 13 then restricting history to NZ would be twaddle. Parochial twaddle almost designed to put adults off history.

LikeLike

Yes I mean 7th form= year 13

LikeLike

On the point of memorising names and dates, although it seems outwardly foolish, I think it must still have a role in education. Memorisation is a skill that can be developed through exercise. The modern pedagogical argument is we can always look it up, sure, but even with brilliant computers and internet it takes time – for most of what we do in our jobs we rely on experience, and a big part of that is pure memorisation of some core facts and experiences. One wonders if the millennial generation will develop the neural structures needed to do that, if their entire youth is based on finding everything you need somehow from the internet. As you say, many children crave facts and figures irrespective of context (my children’s favourite game is of course memory). I wasn’t implying learning facts or memorising details is completely wrong, but it would be wrong to make it the foundation of the educational model.

On the school choice topic, its interesting if parents in NZ ever have the choice, even where a state school is chosen by zoning, it inevitably involves schools which follow conservative, often old-British style teaching methods… little group work, stodgy old subjects, memorisation, followed by big exams…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I agree. (And as I read your comments I was reminded of my year 8 daughter who thinks it is incumbent on me to know the names of all the All Blacks, by position, by province etc, and is testing me on it every afternoon until I get it right – she being something of a rugby junkie, I having fairly little interest…)

LikeLike

Dayomo, Question 13 is very important as continents determine the boundary of a countries maritime border in the ocean. It has all to do with who owns the resources within that boundary. NZ after having been declared a new continent called Zealandia our maritime ocean boundaries are now one of the largest in the world. Of course our dumb and stupid Labour/NZFirst/Greens government banned any mining offshore locking away trillions of dollars of wealth from our tiny population and relegating our poor to sleeping in cars and garages.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Damoyo, Question 7 clearly, the Land Court was created by the British and was intended for new NZ migrants to buy Maori land from Maori owners usually for some kind of consideration. What is not clear as is in Ihumatao if the land was confiscated and then private titled to be sold to private interests? This would be highly unusual as the British Crown would usually own the land on behalf of the Queen. The confiscation would be due to some law breaking as we see today where under the proceeds of crimes act, private property and other wealth possessions are seized by the crown and subsequently auctioned to private interests.

LikeLike

Damoyo, Question 9, distance covered. There is a superficial argument by NZ economists that we are not able to build mass production factories and are relegated to developing primary industries because of our isolation and distance. But cannot explain why other manufacturers outside of NZ are able to easily transport products to us over that same distance and isolation. The answer quite clearly is due to market size, market access and pricing rather than distance.

LikeLike

Getgreatstuff – you miss my point. There is no coherent classification of a continent – therefore we should not evaluate people’s knowledge on a list of alleged continents. Sometimes for example, you see “Oceania” listed as a continent instead of Australia… Eurasia could arguably be a continent rather than Europe and Asia.

Re question 7, the court was intended to create individual title – sale becomes one option of many once one holds a property right. Anything beyond this becomes speculation, admittedly speculation historians can engage in with some authority.

Land sold should be distinguished from confiscated land – my understanding of Ihumatao was that it was part of the land confiscation made by the British following the Waikato tribes rebellion. This land was not included in the Tainui settlement in the 1990s, but the grievance itself ought to have been covered by the generous cash settlement (and land grants in other parts of Waikato). I am not clear why anyone bothers discussing it…

LikeLike

Ihumatao is on the discussion agenda because our dumb Jacinda Ardern decided to put the government in the middle of disputes between an unruly Maori mob trying to seize control of private titled land.

LikeLike