There has been a series of Tuesday events (“Tax on Tuesday”) held at Victoria Univerisity recently, jointly promoted by Tax Justice Aotearoa, the PSA, and the university’s own Institute for Governance and Policy Studies. I wrote about one of the earlier events here.

The final event was held this week, marketed as “Where’s the party at?” Political parties that is. In an event moderated by the Herald’s Hamish Rutherford, speakers from four political parties (NZ First declined the invitation) each spoke about some aspect of tax policy for 8-10 minutes, with plenty of time for questions. It wasn’t a hugely well-attended event, but it is pretty safe to assume that the overwhelming bulk of the audience was on the left of the political spectrum, and I guess the speakers recognised that in what they chose to say.

First up was ACT’s David Seymour. He started well, talking about twin challenges for New Zealand around (lack of) competitiveness/productivity and about (insufficient) social mobility and the spectre of entrenched disadvantage. He was bold enough to note that there is a large group, mostly Maori, who – rightly and reasonably – feel that the last 30 years has not done much for them, in economic terms. I was still with him when he argued that the way to fix the housing market was at source – around the RMA and associated land use restrictions – not by trying to fiddle the tax system.

But his centrepiece was an attempt to make the case for a flat rate of income tax (I think set at 17.5 per cent), scrapping our current progressive system. He attempted to support this with the suggestion that all the rest of our tax system was flat, but I couldn’t quite see the relevance of his point, since (a) personal income tax is almost half of government revenue, and (b) we’ve chosen to achieve the desired progressivity through the income tax rather than, say, the consumption tax. Attempting to engage his (left wing) audience he attempted to argue that we should think of “fairness” as involving the same rate of tax on every dollar of income (with a half-hearted suggestion that a poll tax could be considered even fairer, but probably wouldn’t fly politically). Progressivity, he argued, simply doesn’t fit with New Zealand’s culture and values as an “aspirational society” and sends the wrong message, wrong values. It wasn’t a description of New Zealand I could recognise, at least any time in the last 100 or more years.

Anyway, Seymour then proceeded to undermine his own argument by addressing the question of “but what about the low income people whose marginal and average tax rates would then rise?” Consistent with his logic, I’d have thought he should have just said “well, tough – this is what fairness is, all paying the same rate on every dollar” (while perhaps making the fair point that many people on the lowest marginal tax rates aren’t there for long). Instead he suggested two possible responses. The first was to use the tax/transfer system to offer a credit to these people to leave them no worse off (ie progressivity, at least at the bottom, by another name) or…..and this is where I had to check I was hearing correctly…..the minimum wage could be increased further (noting that employers could “afford it” because their own tax rates would be lowered). In a country with one of the highest ratios of minimum wages to median wages, the MP for the libertarian party appeared to be seriously proposing increasing that impost further……

The Greens finance spokesman (and Associate Minister of Finance) James Shaw – the calm and relatively sensible face of the Green Party – was up next. I’d never ever vote for them – the party that, among other things, whips its members to vote for abortion – but there was something refreshing in hearing a serving minister frankly state (in answer to a later question) that he really didn’t think taxpayer money should be spent on subsidies for the America’s Cup. Perhaps he could next offer some thoughts on (New Zealand) film subsidies to makers of propaganda films vetted and controlled by the Chinese Communist Party? He also spoke highly of a recent NZ Initiative report.

Anyway, on tax, Shaw was clear about where his priors were (and, of course, most of the audience weren’t minded to object). He is keen on Northern Europe and Scandinavia. He characterises those countries are starting by identifying what they want to achieve (desired outcomes) and then work from there to an appropriate tax system. In all cases, that means much higher tax/GDP (and, of course, spending/GDP) ratios than in New Zealand. From his perspective, he’d be keen on more environmental taxes and – the Elizabeth Warren side in him coming out – on taxing wealth relatively more.

Perhaps somewhat at odds with the environmental point, he made the interesting argument – with which I’d sympathise – that we should hypothecate (ring fence, not into general government revenue) revenue from Pigovian taxes, lest government forget why the taxes were imposed (to deter the behaviour) and become reliant on the revenue (eg tobacco taxes). That sounds fine – and he went on to note, in the same vein, that his ideal carbon price in 2050 would be zero (carbon emissions would have been successfully eliminated or out-competed) – but it would leave the pot of general revenue not looking any much larger than it is today. Despite his evident preference for a much larger government, he didn’t dwell on where the credible sources of much higher long-term revenue were in the Green Party’s view of the world.

Deborah Russell, chair of the Finance and Expenditure Committee, and a former tax academic and official, represented the Labour Party. As she noted, she came along – rather than the Minister of Finance or Minister of Revenue – because people would pay less attention to her. As she noted, Labour doesn’t have much to say because – having junked a capital gains tax – they are in “pretty intense” debate as to what their tax policy next year should be.

Russell – who people seem to regard quite highly – was an odd mix of the conventional and aspirational. She ran a very similar line to Shaw in suggesting that we should first identify what we want to spend money on – while noting that Labour hadn’t done those conversations that well – and only then identify how best to pluck the goose. Since she went on to answer a question about inequality later, claiming that she wanted New Zealand to be “the most equal” country in the world, wanted “real radical equality” and supported more support for children, including a return to a universal family benefit, it seemed pretty clear that she too wanted a bigger government and thus materially more tax.

But at the same time she was talking about broad agreement on the “broad base low rate” mantra that has (mis)guided New Zealand tax policy for decades – even though the high tax countries (eg Scandanavia) she seems to admire don’t have BBLR because they can’t (they recognise a need not to overburden business investment). And she noted that when her Labour people talk about taxing the rich she often reminds them to think harder about “who are the rich?” and how many (few) there might be to pluck. The Stuff article on this event played up talk that Labour is looking at campaigning on a higher maximum marginal tax rate, although it is hard to imagine there is really much money in such a proposal (and while it is one thing to campaign for higher taxes from Opposition at the end of a tired old’s government’s term – as in 1999 – it might be another thing now, campaigning for re-election, with Budget surpluses).

National’s Paul Goldsmith – who has actually written a fascinating history of New Zealand tax policy – spoke last. He was pretty underwhelming on this occasion, perhaps concluding his audience wasn’t likely to be sympathetic anyway. He repeated the BBLR mantra, talked briefly of National’s (sensible) policy of indexing income tax thresholds, and repeated the promise of no new taxes in the first term of a National government. He sounded quite pessimistic about fiscal prospects – talking about the risk any new government could inherit material deficits – which would act as a constraint on any desire National might have to do something more about lowering taxes. As for growth/productivity/competitivess, all we heard was the short-term stuff about current low business confidence etc.

Question time followed. James Shaw was challenged on his line, from earlier in the year, that the government wouldn’t deserve to be re-elected if it didn’t introduce a Capital Gains Tax. To his credit I guess, he looked abashed, mumbled a bit, and didn’t really pretend to have an adequate answer.

Herald columnist Brian Fallow asked about low household savings and low business investment/ “capital shallowness” (including the alleged ”overinvestment in housing” and asked what parties were proposing to do. Here, my view of Russell started heading downhill. There isn’t a low savings rate, she claimed, just the wrong measures of savings, and as for business investment, why 1 per cent interest rates might bring about desired change – as if rates aren’t low for a reason – and repeated that (deeply flawed) Adrian Orr line that interest rates are now just returning to more normal long-term historical levels. Goldsmith and Shaw at least both suggested that any housing issues were housing market problems and need to be fixed at source. But not one of the three of them (Seymour had to leave early) even mentioned the company tax rate (or cognate issues). All three – Russell and Shaw more than Goldsmith – actually seemed keen on taxing multinationals more heavily. None showed any sign of engaging with the literature that much of the burden of capital taxation falls on wage earners.

The chair of the Tax Justice Aotearoa group noted that on OECD measures New Zealand is around the middle of the pack on inequality and asked the speakers whether they were happy with that, and if not which country they would aspire to be like. I’ve already mentioned Russell’s response, although shouldn’t omit her suggestion that as a result we need to look a lot more seriously at what we don’t tax: wealth. The CGT had been rejected but she argued we need to relook at options that tax wealth.

Paul Goldsmith responded that he wanted to emphasise equality of opportunity, while noting that the state – rightly in his view – does lots of redistribution as it is. James Shaw, while rejecting the idea of a single country to aspire to, was quite open about aligning more with the Nordics – in his view they had the best outcomes and were the best run. By contrast we had “emaciated social support over several decades”, and he went on to note that we couldn’t, in his view, have equality of opportunity without much more government spending (“investment”).

It was interesting to hear both Shaw and Russell suggest that there should be more focus on desired outcomes, which should then lead us to design a tax system that would raise the (more) money. Arguments on that sort of point are part of what politics is about. But it was also interesting to hear both of them talk about how politicians end up disguising revenue increases in various not-very-transparent guises (levies etc) and how hard it is to make the case for higher taxes (although as Paul Goldsmith noted, one of the striking things of the CGT debate was the way Robertson/Ardern simply didn’t engage in making the case). Perhaps the left really can make the case for much more spending, much more tax, but their own words suggest they have something of an uphill battle.

As for me, I probably came away still disinclined to vote at all next year.

But, for what it is worth, two final points. First, it is easy to admire the Nordics. But they’ve built really strong economic foundations, which we simply no longer have. Here are the latest OECD real GDP per hour worked numbers

| Denmark | 65.4 |

| Finland | 55.3 |

| Iceland | 56.9 |

| Norway | 80.5 |

| Sweden | 61.9 |

| New Zealand | 37.3 |

And not one of the speakers showed any real emphasis on getting the conditions right for markedly lifting productivity (not even Seymour, despite the opening reference). Parties just don’t seem to take the failing seriously, and continued failure to do so will increasingly constrain both public and private consumption/service options.

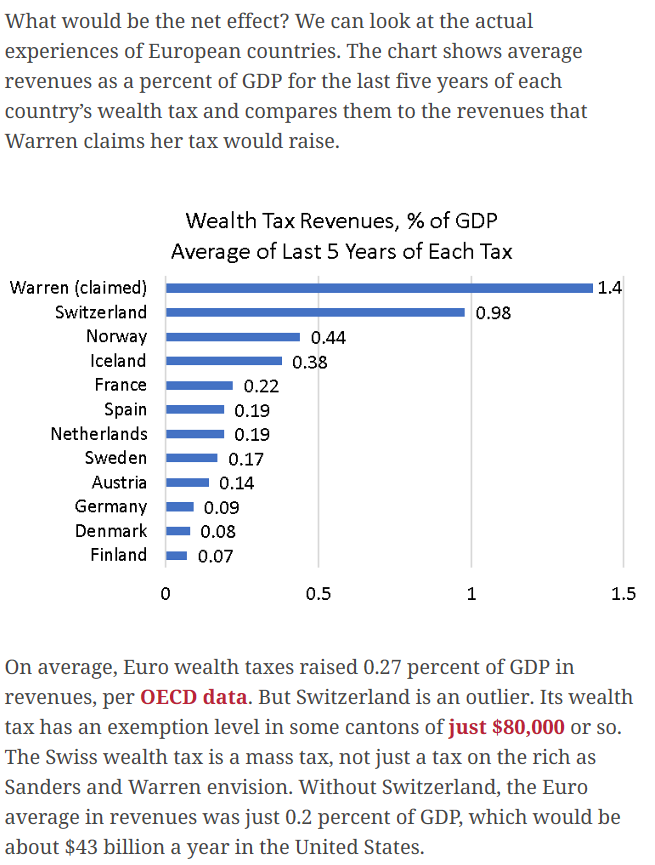

And, as for wealth taxes, I happened to see this table in a Cato Institute piece the other day.

You might end up favouring a wealth tax for some principled purpose, or just as an “envy tax”, but it isn’t likely to be the sort of option that is going to dramatically transform the size of government, in New Zealand or anywhere else.

Reblogged this on Utopia, you are standing in it!.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A land tax, possibly with a credit towards income tax liability on that land, still seems like a good idea to even up the tax system.

The marginal income tax rate for people on the average wage is far too high at 30%, and the company tax rate is too high as well if we want to encourage business investment.

The other thing that the Economist was pushing a year or two ago was getting rid of the deduction for interest, which would allow headline rates to be lowered – but no doubt would have to be phased in to stop heavily indebted farmers, etc going bust.

LikeLike

We do have land tax. It’s called Rates. I already pay $40,000 in rates a year.

LikeLike

Rates is of course a local tax and contributes nothing (apart from GST) to central government so is not a true land tax that can be used to fund central government activities. I would favour it being used as a substitute for income tax for the many land owners like landlords and farmers who currently pay little if any income tax on the activities of their land.

LikeLike

I thought you would say I don’t pay any of that as the tenant pays for it and that would be correct. Similar to rates, land tax is a cost which would put upwards pressure on rents. Therefore ultimately it is not the property owner that pays the land tax but the tenant of the property.

LikeLike

Landlords can only charge the rent the market can bear and if a land tax levelled the playing field so they were all paying similar amounts of tax then those formerly paying tax less couldn’t just raise rents to recover their extra costs! House prices might actually drop because the return for geared up landlords would drop.

LikeLike

I agree with an increased land tax, but only if the RMA is significantly freed up at the same time.

It would help drive efficient land development.

LikeLike

The rent ceiling is steadily rising and so is the governments accommodation supplement of now $2 billion a year. A land tax like rates is only effective if it is applied to all property owners which makes it more difficult for owner occupiers and advantages to property investors who can pass that costs onto tenants. With Air BnB rents can reach the heights of what a tourist will pay on a daily basis and not just limited to what renters can afford. Rising numbers of occupiers per household also equates to more people paying the rent. The market can bear a higher rent for sure.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Crikey,

you do not have a capital gains tax. Very Amos and micaish.

Wealth taxes do not get a lot of cash but do assist in gaining more income tax because of reduced tax avoidance

A tax on land is ideal. Qery progressive and you cannot avoid it.

LikeLike

That’s a lie. We do have a 5 year Capital Gains Tax on sale of investment property called the 5 year Bright Line Test. The CGT rate is 33% as it is added to your wages for tax purposes. One of the highest CGT rates in the world.

LikeLike

does it only apply to property?

LikeLike

The Bright line test is a CGT on property. There is a separate Controlled Foreign Corporate tax and Foreign Investment Fund Tax which are taxes on foreign owned companies and share portfolios. NZ is heavily overtaxed not undertaxed.

Even flipping property attracts GST as well which makes property trading effective tax rate as 41.5% compared to workers top tax rate of 33%.

LikeLike

You state in respect of the Nordics:

‘But they’ve built really strong economic foundations, which we simply no longer have.’

How did they go about building these foundations? From afar it appears that there was a lot of state intervention both at the national and supra-national (EU) level.

Hypothetically if New Zealand was to build similar foundations so that (some) politicians (and those in the audience the other night) could build their dream of a Nordic nation in the South Pacific what would such interventions (from the state) potentially look like?

LikeLike

I think you’ll find that state interventions in building the Nordic countries is a myth and it is the strong private sector that is the strong foundation, helped by what were very mono-cultural societies. I understand that even today that businesses are relatively unconstrained compared to most European countries so it is relatively easy to hire and fire – with workers protected by a strong welfare state (rather than heavily regulating the businesses themselves).

LikeLike

They differ. For Norway, oil and gas are of course the really big differentiating factor, and for Iceland fish and electricity (both countries have small populations relative to the resource).

Denmark and Sweden are both part of the swath of N European countries (France, Belgium, Lux, Neth, Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Austria, Switz) with really high real GDP per capita, and typically big strong internationally oriented companies (and despite having quite high taxes, they often have fairly enabling business regulatory environments).

I’ve argued that we could not replicate most of that success here – remoteness is a constraint we just can’t change. In that sense, the Icelandic story is prob more relevant – we’d have been far better to have kept policy small relative to our (really quite limited, accessible) natural resources. Of course, there is other stuff we could do – the Nordics typically have much lower corp tax rates than their max personal tax rates, and our business regulatory environment which was among the best on OECD ratings 20 years ago is drifting back towards the middle of the pack now.

By and large, the big govts in those countries doesn’t look to be in any material sense a cause of their high productivity/prosperity, but it is fair to note that it hasn’t unduly held them back (GDP per capita in those countries is similar to that in the US, and ahead of that in Australia, both of which also have materially smaller govts).

(And before people talk about investing in skills etc, recall the OECD data suggest adult skills in NZ are among the highest in the OECD, notwithstanding problems in the tail.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your reply.

So in that situation where does New Zealand sit relative to the Nordic countries with respect to the business regulatory environment?

If we have drifted back and a component of the Nordics success is thanks to their business environment settings where do they currently sit?

What sort of business regulatory settings would need to be changed in New Zealand to get us to the top of the OECD on that particular measure and what would the size of the changes required be like?

LikeLike

I might come back to this next week, but here are some indicators to be going on with https://www.oecd.org/economy/reform/indicators-of-product-market-regulation/

Note that I am not suggesting that even with world-leading regulatory policies we could match the Nordics in GDP phw, but we could make some inroads on say Denmark and Sweden.

The biggest single issue for NZ remains rapid (policy driven) population growth in a very remote economy that remains heavily dependent on fixed natural resources. We have smart and skilled people, but their skills would typically be more remunerative elsewhere, closer to global centres of econ activity.

LikeLike

I guess at the heart of my inquiry is if there was a dedicated project to get New Zealand to the frontier of regulatory settings (a 2035 taskforce perhaps…?) and was successful in achieving this.

Then the constraints of distance, population already here and fixed stock of natural resources notwithstanding then what potential GDP phw might New Zealand be able to achieve? 10% higher than now? 50%? 100%?

LikeLike

My guess would be 10% – which would be huge as these things go.

LikeLike

Finally we are seeing what a infant NZ Space industry is worth from a MBIE study, is $1.7 billion without any government subsidies. Unfortunately Rocketlab that kickstarted our Space industry is owned by USA bought for a song at $300 million. We will spend $1 billion in taxpayer subsidies for disease control in the primary industries killing cows and ripping up kiwifruit vines. It is not because that is all NZ can do, it is because we have been misled by our expert economists to misdirect our resources towards primary industries.

LikeLike

American President John Adams once said, “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious People. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.”

The same could be said for democracy. A moral and religious people are inclined (for the most part) towards diligence, self-control, thrift, deferred gratification, functional families, intergenerational wealth creation, good citizenship, charity and productive lives.

Regardless of what kind of people we may have been 100 years ago, we are not approaching a ‘moral and religious people’ today. We have elected successive governments who have promised to deliver everything for us, ranging from economic security to personal wellbeing. It was another American President, Gerald Ford, who said: “A government big enough to give you everything you want is a government big enough to take from you everything you have.”

We no longer have ears to hear the kind of political wisdom delivered by Ford and Adams.

So then, how is 100 years of State paternalism working out? Today we have approaching 25% of the nation’s school children living in households entirely dependent upon welfare, the vast majority in single parent homes. Which is to say they are living in relative poverty, and subject to all of the negative social indicators that implies, substance abuse, violence, familial dysfunction, educational failure and underemployment.

http://archive.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/people_and_communities/Children/nzs-children.aspx

I don’t have the stats to hand, but I suspect a significant portion of the remaining three quarters of the nation’s school children are beneficiaries of ‘working for families’, another act of State paternalism that has created significant levels of middle class welfare dependency.

By any objective measure, these statistics indicate social and structural failure writ large.

Such is our addiction to State paternalism it is now politically impossible to implement meaningful taxation reform, unless politicians engage in deliberate deceit, promising one agenda and delivering another. Ok, well maybe it is possible!

But seriously, governments have no more ability to create economic equality (even if it were desirable) than they have to influence the tides, or to change human nature. We already live in a highly redistributive tax environment and the idea that an adjustment to the tax system will usher in a more just and equal society is plainly absurd.

There is an old proverb that says “when the foundations are destroyed, what can the righteous do?” It can be argued that State paternalism along with social liberalism has undermined the family, and progressively destroyed the foundations of our social order.

Consequently, I do understand why you consider voting to be an act of futility, at least in the current political and social environment.

LikeLiked by 6 people

“….supported more support for children, including a return to a universal family benefit, it seemed pretty clear that she too wanted a bigger government and thus materially more tax.””.

I’m delighted to find a second person in NZ wanting a return to a universal family benefit. Obviously it would require more tax revenue but I do not understand the ‘bigger government’ – it would replace many means tested benefits such as accommodation allowance and WFF and result in a reduction in WINZ employees.

BTW: impressed by Brendan McNeill’s comment.

LikeLike

There are others. The 2025 Taskforce’s first report explored the option, but didn’t take a view for or against. From memory, the chair (Don Brash) was quite keen. The difference from Russell perhaps is that the 2025 Taskforce was looking at pulling back a bunch of other spending, not increasing the overall govt spend.

LikeLike

Bob those other benefits vary according the situation of claimant, including how much their accomodation costs are so no, a flat rate family benefit would not replace them – but might reduce them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Anthony, I meant a seriously generous universal child benefit so certainly requiring an increase in tax to pay for it. If generous it would replace WFF and reduce various benefits for the unemployed.

I’ve been looking at accommodation allowance because of grandchildren on the way; it is difficult to find a clear explanation but using the WINZ benefit calculator and entering one or two children does appear to be significant. Accommodation supplement benefit seems to have many of the failings of a benefit system imposed from above by well paid people with little idea of living within a tight budget. For example if you have savings of $7,999 then you may be liable to receive $305pw but if some mean person accidentally puts $2 in your bank account you get nothing. If you decide to move from your expensive city accommodation to a cheap area of NZ where you can grow your own vegetables then the max benefit drops from $305pw to $120pw. If you are unlucky a move across the road can drop the amount received by $85pw. The penalty for moving to a rural area is directly opposing Shane Jones efforts to stimulate our regions. Having a second child increases maximum benefit by $70 in Auckland but only $40 in rural NZ. It is weird, arbitrary, bureaucratic and probably expensive to administer.

The return to a serious universal child benefit would not be popular with my single friends nor many of my fellow pensioners however philosophically it is just a sensible investment in the future of our country and it meets that specific NZ value: fairness by helping all children have a good start in life. The level playing field.

Brendan McNeill points out that 100 years of state paternalism may have been well meaning but is a dire failure for at least 25% of our children. A universal benefit is not paternalistic; it would not dissuade parents from working and saving.

LikeLike

Bob at least your solution would largely get rid of the very high effective marginal tax rates that a lot of families currently face.

LikeLike

Anthony, True, I arrived 16 years ago with four children and a few years later a couple of them were students living at home but receiving a means tested student allowance and two were relevant to our means tested WFF – I estimated every extra dollar of income had about a 70% effective tax and as a contract computer programmer working from home a few days per month with reasonable savings and a working wife it just didn’t seem worth the cost and effort of looking for more work (other factors being transport and smart clothing costs, finding someone to look after our primary kid after school).

Of course some benefits must be tested – for example I had a neighbour with severe medical problems from birth – but in general the fewer the number of means tested benefits the better.

LikeLike

I couldn’t attend this event, but from your description there seems to be little discussion among NZ’s major parties about whether the basic “broad-base, low-rate” strategy New Zealand adopted more than thirty years ago is actually working. Since the reforms of the 1980s and 1990s, New Zealand has a tax system that has some of the highest taxes on capital incomes in the OECD, and some of the lowest taxes on labour incomes in the OECD. It has low top marginal tax rates on labour income. It has some of the most distortionary tax policies in favour of owner-occupied housing relative to investment in other assets in the OECD.

Basic tax theory says you would adopt this type of policy if you wanted

High labour participation.

A business environment unfavourable to capital investment.

An investment environment biased towards residential property.

Low capital intensity.

A favourable tax environment for high income salary earners.

A not-particularly progressive tax system.

Casual empiricism suggests we have a country with

High labour participation rates and long working hours.

Low capital intensity.

Low productivity and poor productivity growth.

High residential land prices.

Only moderate redistribution.

I have been saying this for years now, and as far as I can see have had zero effect on the public debate. That is fair enough: New Zealand seems to be getting the outcomes it wants from its tax system, and there clearly isn’t appetite to change the policies. You have to respect the wishes of the people. But I can’t understand why it wants these outcomes. So here is the question. Have New Zealand tax policy makers actually got a sensible objective for tax policy, or have they got confused between their objectives and their policy instruments? The broad-based low-rate policy should be a tool for achieving an objective, but it seems to have become the objective in its own right. In the standard optimal tax literature, it is not optimal to have the same tax rates on different types of income, but New Zealand now treats this principle as sacrosanct (it wasn’t even questioned by the Tax Working Group).

Lastly, the Hall-Rabushka flat tax proposal had a tax-free threshold which does lead to a somewhat progressive tax system. However, the Hall-Rabushka tax proposal was actually a clever way of converting the tax system to an expenditure basis rather than an income basis – something one would think was consistent with a green economy as it taxes what you take from society, not what you put into it. Bradford showed you could extend the principle and get whatever degree of progressivity you wanted with an expenditure tax system, although by giving up the flat-rate principle.

(And, by the way, it simply makes no sense at all to say that tax should not affect land prices, unless transport costs are zero. I can’t remember reading any theoretical or empirical papers in the tax literature that argue for this position. The principle that tax policy doesn’t affect land prices or only has a minimal effect on land prices seems to be a peculiarly New Zealand invention, and as far as I can tell has never been backed by any theoretical analysis or empirical studies.)

Andrew,

who sometime ago concluded he did not understand the underlying sociology of New Zealand’s tax debates.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well articulated Andrew

+1

LikeLike

The general consensus is that GST works. However the rate at 15% puts us at the very top in the world and does create pricing anamolies in the market.

It is not true that there is a principle belief that tax policy have little or no impact on land prices. The problem resides in excluding owner occupied land from Capital gains tax or a land tax. It is that stubborn exclusion of owner occupied land that minimises any taxation policy on land prices.

When CGT on investment property was introduced via the Bright Line Test tax at 33% one of the highest CGT in the world. It has already proved little or no effect on land prices.

LikeLike

Can I ask why is it not applied to the sharemarket. That is absurd and highly inequitable

LikeLike

To be honest, you are probably off not asking. The short answer is politics. The “brightline test” on rental properties – far from a true CGT, nearer a turnover tax – was just a knee jerk reaction to a political itch a few years ago. There is no general consensus in NZ in favour of a CGT.

LikeLike

Thanks, strange system.

LikeLike

A reply to “Get Great stuff”

According to the OECD, in 2018 there were 6 countries with lower headline GST rates than New Zealand, and 30 countries with higher GST rates. This scarcely makes us the country with the highest GST in the world.

Of course, GST is applied more comphrehensively in NZ than other countries. In terms of the amount of tax collected on goods and services as a fraction of GDP, NZ is 12th in the OECD (according to the OECD).

The Tax Working Group did report that NZ had the highest GST tax as a fraction of GDP in the OECD in several of their reports. They were deliberately misleading in reporting this, however, noting in footnotes that this was because NZ includes GST on government purchases between different branches of Government, a practice not followed by any other country. This amounts for about a quarter of the GST they included in the statistic that ostensibly shows NZ has the highest GST collection the world. (The NZ Government does not do this when calculating the total tax take of the Government as a fraction of GDP.) So, if you use accounting practices not used elsewhere in the world, and not even used by all branches of your own government, practices that add a third or so to the amount of tax revenue you collect, you can show that we have the highest GST in the world. I guess creative accounting types like to do this.

The TWG’s willingness to play fast and loose with statistical measures was rather unfortunate. It created a lot of work for people wanting to take their report seriously as it meant that almost all of their empirical assertions needed to be independently assessed as they could not be relied upon to be meaningfully accurate. I guess this is what happens in politically-driven environments.

LikeLike

I guess the key countries which are our significant trading partners like Australia, Japan, India, Taiwan, Thailand, Malaysia have a lower GST. The other countries have a higher VAT which is not quite the same as GST.

LikeLike

GST is a tax of the consumer sales price. VAT is a tax on the margin increase. A percentage of Sales price is significantly higher than a percentage of the increased value margin. It is not even comparable.

LikeLike

Actually, they work out to be exactly the same; it is simply far more efficient to collect taxes at each stage of the value-added chain,than to only collect them at the final stage becaue you minimize fraud (there are two receipts at each stage.) In NZ the goods and service tax is collected in the same way as foreign value added taxes are collected, for the same reason.

LikeLike

Andrew Coleman, you are wrong. It is not the same.

In the UK as an example, the default VAT rate is the standard rate, 20% since 4 January 2011. Some goods and services are subject to VAT at a reduced rate of 5% (such as domestic fuel) or 0% (such as most food and children’s clothing). Others are exempt from VAT or outside the system altogether. Most supplies of food of a kind for human consumption are zero rated

In NZ all goods and services are subject to a flat rate of 15% GST on the sale price. But not all input costs are subject to GST ie zero rated which means more GST is collected on the sale price than the VAT methodology collected on the net margin.

LikeLike

Michael, you are wrong. The Bright Line Test as a turnover tax is a John Key lie. He was prompted by Alan Bollard in RBNZ statements that put John Key’s National government in a difficult corner that required a response. John Key put in the most palatable type of CGT that he was able to get across the line without upsetting the public.

The Bright Line Test is intended for people that had no intent to trade property. If they had intended to trade property then GST would have applied as well as income tax. The Bright Line Test is not a turnover tax as it has no GST applied to it. It is intended to be a Capital Gains Tax but treated as income tax and therefore subject to 33% income tax. China has a 5 year CGT on property at 20%.

LikeLike

I meant my comment more loosely. It only captured people who did turnover a property within two years. So it is akin to a CGT for those people, but not for anyone able to hold beyond the threshold.

LikeLike

Could those more knowledgeable than me about the economic benefit that a stable, homogeneous population living in a country with upto a thousand years of infrastructure built progressively over time contributes to the current gdp figures? I always find it very inconsistent to compare New Zealand’s economic performance to Nordic countries just because they may have comparable population and / or landmass.

New Zealand settlers only started developing this country in the 1850s with a very small population to do it. Compare that to the sophisticated cities (for their time) that Norway or Denmark had then? Isn’t it reasonable that New Zealand lags behind?

LikeLike

Perhaps the easiest answer is simply to note that 100 years ago we were richer/more productive than all those old countries (US, Aus and NZ were the three highest income countries, with the UK not far behind).

We’ve really only fallen materially behind the Nordics in the last 50 years or so, suggesting the issues are more about policy choices (given resources, geography) than past development (remembering that the bulk of people in NZ, and other colonies of settlement, are themselves heirs to whatever the development of those cultures contributed to current prosperity there and here.

LikeLike

Don’t forget back then we did not count Maori or women as people. Therefore the productivity numbers were somewhat badly skewed

LikeLike

GGS – surely in 1900 NZ did have women and native Maori voting so therefore recognised. It was other countries that were slow to count them.

I was understanding productivity as total production of a country divided by total population and that would include everyone.

LikeLike

Was one of the major reason New Zealand was so ‘productive’ because of a very low optional. This was the case in Australia.

LikeLike

Back then, the right to vote included property ownership. Maori however mostly lived on communal land meant that only a few Maori actually could vote which also meant few women could vote as well as it was mostly husbands that owned property.

LikeLike

That simply isn’t so. By 1867 all Maori men had the right to vote, and the 1893 reforms extended that to all Maori women as well.

https://teara.govt.nz/en/voting-rights

LikeLike

The popular view of Nordic countries expressed in the summit appears to have been taken through the rear-vision mirror. Sweden’s open boarder policy of recent years has changed the social dynamics considerably. They now have ‘no-go’ areas in cities like Malmo, and have had something like 200 bombings this year in public areas including apartment buildings and police stations.

Recently neighbouring Denmark has instituted boarder controls with Sweden following 13 bombings in Copenhagen since February. Denmark police believe they have been carried out by ‘Swedish citizens’.

None of this is considered newsworthy in our media because it offends the popular narrative. Diversity is our strength etc.

Big government welfare states require homogeneous populations to maintain popular support. No one wants to see their taxes spent supporting violent immigrant criminals in their neighbouring suburb.

Our politicians seem keen to learn from Nordic countries past successes, but are apparently blind to their more recent failures.

LikeLiked by 4 people

All a bit mystifying

Sounds like a Yak-Fest about increasing the tax-take as solutions to undefined problems other than inequality. Since when has tax-redistribution been a direct panacea to fixing inequality.

One would imagine it is essential the cake is correct-weight and full measure and everyone is contributing their fare share before debating how to carve the proceeds up.

For many years NZ has had a pseudo capital gains tax on profits made from the renovation and flipping of housing based on the “intention” test. Apparently the Inland Revenue had difficulty administering the law. Then National introduced the 2-year Bright-line test. Then Labour Coalition extended that out to a 5-year bright-line test.

How’s that going? Any news?

Hardly a day goes by without a report in the NZ Herald about some tax scam or article about visa migrant exploitation all of which are founded on not paying income-tax or GST or ACC

the invisible economy – This is the latest from yesterdays Herald

“Min Ji said her family moved to NZ from China in search of a better life, and never in her worst nightmare imagined her builder husband would die in a workplace accident. The 36-year-old widow, whose husband died last month in a workplace accident, has been handed a second shock after being told there was no record of him having had any income when she applied for support from the Accident Compensation Corporation”

https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=12285188

LikeLike

Three years ago I wrote to the then minister responsible for immigration saying immigrant visas should be matched against IRD annual returns. It would do two things produce evidence supporting the argument that skilled immigrants are skilled and net contributors to NZ and secondly it would help identify the cheats and the criminals. I wrote after a reported drug importing scam where the Chinese permanent residents had been in NZ for 9 years but never paid tax. The answer from INZ was that it breached privacy.

My son is an apprentice builder and always hard up but pays his income tax; I intend sending much the same letter asking why INZ could not detect this fraud.

In the specific case reported in your link I feel sympathy for this woman and her child; in the fair and kind society NZ claims to have she should be compensated by deductions from the generous salaries of the Minister for Immigration and the Privacy Commissioner.

LikeLike

Have a close look at that NZ Herald article …..

From the information given it would appear that ACC is data-matching with IRD

I think your correspondent is lying and giving you the “go-away response

LikeLike

Here’s another one

Temple to pay $100k for breaching employment laws

Weigh up the PAYE tax-avoided and ACC

https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/117040153/sikh-temple-to-pay-100k-for-breaching-employment-laws

LikeLike

Two major companies, Fletcher Building Ltd and Fonterra Ltd won’t be paying any income tax for the next few years

LikeLike

Here is a list of companies operating in NZ – in descending order of capitalisation

Examine them and you will find all the electricity gentailers and retailer in the list – all earning monopoly profits and paying tax. Trustpower which s not the biggest power company earned $100+ in profits and paid $37 million in company tax.

One you wont find is Wellington Electricity Ltd which makes no profits and pays no tax. You wont find Google or Facebook or many other US companies operating in NZ and not paying tax

NZ Government’s of both stripes have failed for years to do anything about it. Lets have a debate about the full collection before discussing how to spend it

LikeLiked by 1 person

List of companies by capitalisation

https://www.value.today/new-zealand-top-companies

LikeLike

Getting rid of the tax deduction for interest would go a long way to ensuring most of the companies you list pay more income tax. Wellington Electricity, for example, was set up in such a way that it would pay no income tax for at least 10 to 15 years.

LikeLike

Antony, I don’t know anything about Wellington Electricity, but what I do know is that you only pay income tax on profits. Many companies run in shareholder funded deficits during their start up years. 10 to 15 years without paying tax means the shareholders have had no dividends during that period.

There may (or may not) have been substantial capital growth during that time, I don’t know, but it seems to me as an investor that 10 – 15 years to wait for a return is an exceptionally long time to provide a service without any material reward. They deserve our sympathy rather than our condemnation! 😉

LikeLike

Brendan try looking up ‘thin capitalisation’.

LikeLike

Seems to relate to foreign ownership. The Ird have highly regulated these kinds of transactions.

https://www.classic.ird.govt.nz/international/business/transfer-pricing/transfer-pricing/practice/transfer-pricing-practice-thin-cap-rules.html

NZ banks are pragmatic risk averse corporate lenders. Borrowers have to operate their businesses within banking covenants else life gets difficult.

If shareholders are acting legally, what’s your problem?

LikeLike

There is still plenty of scope to structure affairs to minimise the tax paid in NZ by a successful company with overseas ownership.

Getting rid of the interest deduction while lowering business tax rates would make taxation of businesses fairer.

LikeLike

Yes – it is foreign owned – the point that can be made is this – Michael among others bemoan the NZ rate of corporate tax is a huge disincentive for foreign capital to come to NZ and invest in productive activity

Wellington Electricity proves that isn’t so – all the regulation in the world is pointless if it isn’t enforced – one need only point to Facebook and Google who do not pay the going rate of $0.28 in the dollar

Would be revealing to see a list of foreign owned entities paying the full rate

LikeLike

I used to work for Rockwell NZ a US company. Rockwell used to pay tax on net profit margin of 20%.on sales. One day the head office came in and decided that the profit margin should be 5% on sales and did a transfer pricing adjustment. IRD did an audit and Rockwell head office sent in a team of tax lawyers. IRD went away quietly.

LikeLike

At the risk of assuming Michael’s role as “Cassandra in Chief” some further observations on the topic of taxes and the welfare state:

It is the habit of governments that lean left to focus upon new ways to extract additional taxes from the productive sector to fund new or expanded Government programs. Ultimately that’s an end game. Death by a thousand increments, if you will.

It is the habit of governments that lean right to leave all new taxes from the previous administration in place. Why risk voter backlash, or be perceived as cruel and uncaring?

The welfare state creates perverse incentives both for politicians and the interest groups they favour. This weakness is built into its DNA. Consequently, we have approaching 10% of all working age adults in New Zealand supported entirely by welfare. I don’t have the figures for (say) 1972, but my sense is that it would be a fraction of that number.

Combine this with the creation of an expanding underclass of disadvantaged and disenchanted young people (see my first comment), we face ever increasing demands on both the justice and welfare sectors. It’s not for nothing this government is seeking to recruit 1800 more police, while also attempting to reduce the prison population (sigh..)

The issues we face as a nation, although affecting government spending, are not going to be solved by government spending. Arguably in many cases they are being made worse by government spending.

However, our politicians are largely silent on these systemic social problems because any attempt to address them would be widely unpopular, perceived to be cruel and uncaring. Which brings us back to John Adams observation as to how unsuited we are as a people for democratic government.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The previous govt’s social investment model was a good intention, no? Track deprivation & chuck resources into the failing families before the kids are ruined forever..

LikeLike

Yes, that was a commendable initiative, however it was John Key in opposition that called WFF ‘communism by stealth’ but left it unchanged during his terms as PM.

LikeLike

John Key is a money machine. He has a natural talent. As the self appointed tourism minister he gave us a mega money machine in getting our tourist numbers to now 4 million and in combination with the international student market he delivered to us a $15 billion a year export industry dealing in pure cash. 100% conversion from foreign dollars directly into the back pockets of small business owners and employees, the purest form of trickle down. Only problem is that it is all low skilled and low productivity enterprises but a significant contribution to housing scarcity and incremental rents.

LikeLike

It would be tempting to vote for a party out there that pledged to do nothing. Politicians doing something to be seen to be doing something can have worse outcomes than ones sitting on their hands.

LikeLike

“Which is to say they are living in relative poverty, and subject to all of the negative social indicators that implies,”

All of this in the context of the highest ever level of education benefiting from decades of research into improving it. Also in the context of the worst ever level of society. Perhaps woke-ness and education aren’t the panacea some believe them to be…

LikeLike