A couple of weeks ago I saw, somewhere or other, a link to a short column (“America’s Argentina Risk”) by the prominent economist Kaushik Basu.

Kaushik Basu, former Chief Economist of the World Bank and former Chief Economic Adviser to the Government of India, is Professor of Economics at Cornell University and Nonresident Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution.

In his column he tells us that he migrated to the United States in 1994. But you don’t have to read the column to get the impression that he isn’t overly taken with the direction of his new country – with rare exceptions (I’ll mention one below), Argentina is usually only invoked these days (indeed for most of the last century) with a “don’t become like Argentina”, or “we are all heading to the dogs, like Argentina” sort of tone. Of the making of books and articles about Argentina there is, it seems, no end (I have a large pile of them on my shelves).

My own first impressions of Argentina were the military regime tossing dissidents out of planes over the ocean and then the invasion of the Falklands. Not all its modern history has been quite that bad, but it doesn’t seem to have much to its credit whether on broader governance or economic performance. It isn’t, say, Somalia or Zimbabwe. But that isn’t saying much. On the IMF metrics, Argentina’s real GDP per capita (PPP terms) now slots in between those of Mexico and Belarus. In another few years even the PRC might have caught up.

It wasn’t always thus. And that is Basu’s starting point.

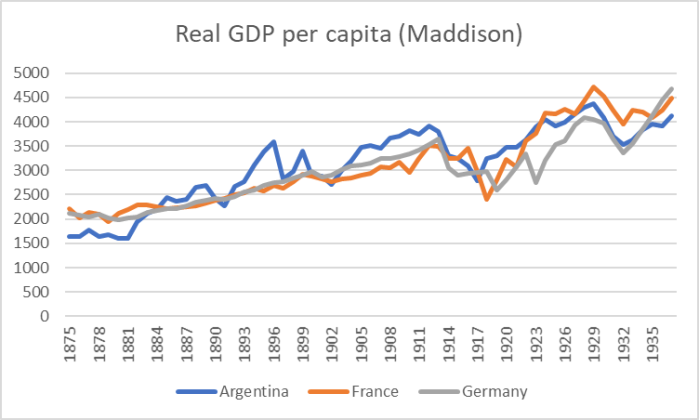

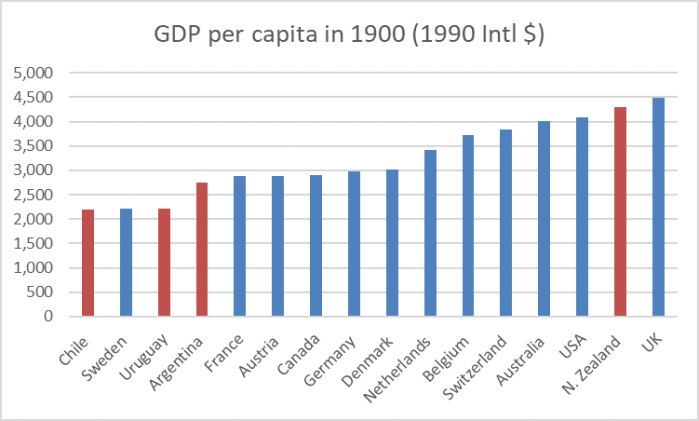

During the first few decades of the twentieth century, Argentina was one of the world’s fastest-growing economies. It also had talent flowing in, with more immigrants per capita than virtually any other country. As a result, Argentina was among the world’s ten richest countries, ahead of Germany and France.

To illustrate the Germany and France point

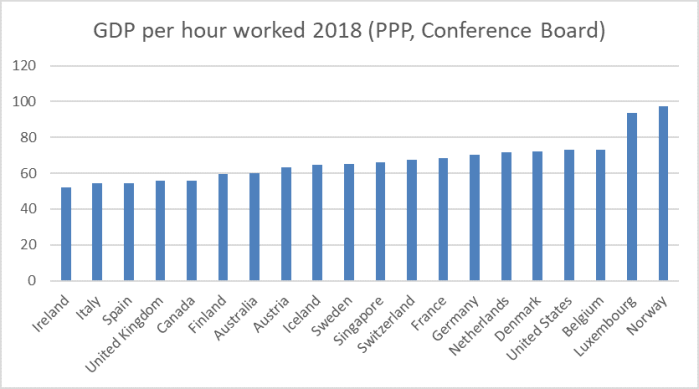

France and Germany were big and powerful countries, but they weren’t exactly top of the top tier per capita league tables. Here is a chart from one of last week’s posts.

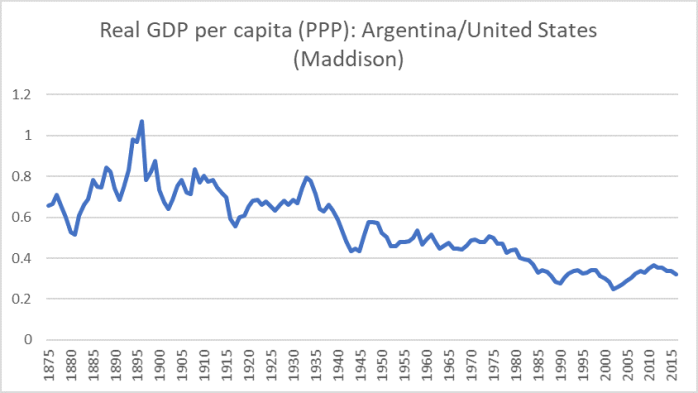

And here is how Argentina compares to the United States, from when the annual data begin through to (almost) the present.

There is short-term volatility and probably still some measurement issues in the earlier decades (you can safely ignore that blip up in the early 1890s (around the time of a massive credit boom and nasty bust, one that almost brought down Barings Bank)). Argentina was managing about 80 per cent of the incomes in the US from the mid-1880s until about World War One. Thereafter, there were really only a succession of steps further downwards every few decades. These days, Argentina is barely a third of the US. It is sufficiently bad that its real GDP per capita is now only about half New Zealand’s.

As Basu puts it – with a similar tone to the one I noted earlier

What followed was not so much a recession as a slow-motion slowdown, the scars of which are visible even today. Argentina thus became a cautionary tale of how a wealthy country can lose its way.

Thus far, no real argument.

But according to Basu this is all the result of an anti-immigrant mentality in Argentina since the 1930s and the US risks heading towards Argentina-like outcomes because of Trump “stoking fears of immigrants and foreigners”. Basu’s is a model in which very high rates of immigration caused Argentina’s decades of quite impressive economic success and, at least by implication, any turning away from such a model threatens all such good outcomes. (He does mention tariffs in the 1930s once, but clearly doesn’t see that as a major party of the story, since there is no mention for example of Trump’s use of tariffs in his jeremiad about the US).

There is rather a lot that is questionable about this story.

But perhaps most obviously, Basu’s story about the decline in immigration to Argentina was more or less mirrored in the United States. Here is a couple of charts from a 1990s journal article (summarised here) reporting a historical immigration policy index for a range of countries (not including New Zealand). Positive scores mean an active bias towards immigration (aggressive promotion, subsidies etc), zero means neutral (in this case, open doors but no active policies one way or the other) and negative scores involve increasingly intense restrictions. Here are the charts for Argentina and the United States.

On this metric, policy in the US was consistently less encouraging than that in Argentina, Argentina’s immigration policies had become progressively less positive even in the decades of greatest economic success, and the tightening in policy from World War One was greater in the US than in Argentina.

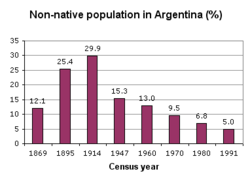

The slowdown in immigration to Argentina was real. Here is the foreign-born share of the population

And in the United States in the 1970 census the foreign-born share of the population was just under 5 per cent.

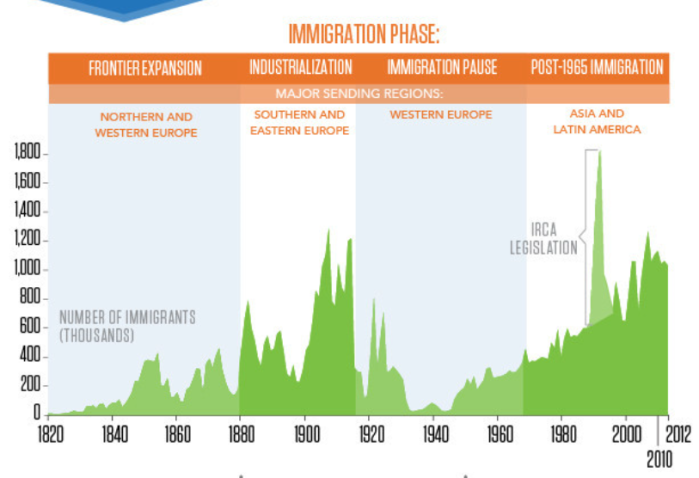

Here is a chart of migration to the US

Net migration to the US plummeted after World War One and remained low for decades (and if you are impressed by the subsequent rise, recall that US population now is more than three times what it was in 1914).

And yet…..was it not in the decades after World War One that the US continued to move to its leading position in the world economy. Were not the 1930s – for all their other problems – the decade in which the US recorded the strongest TFP growth ever (on that measure, the 1920s was the second fastest)?

I am not, repeat not, arguing that markedly slowing immigration to the US was in any sense the cause of those US economic outcomes, but it is somewhat staggering to find a leading economist suggesting that (lack of) immigration was a major explanation for Argentina’s decline when, writing about the US, he pays no attention to the sharp decline in US immigration at much the same time, when the US went on to be the only New World economy still in the very top tier of economic performers today (and even today – whether under Bush, Obama or Trump – immigration to the United States is pretty modest in per capita terms). Here is another chart from last week’s post.

Whatever you might think of Trump – and I’m no fan on any count – it is hard to see the US yet being pushed down the ladder.

(Argentina’s real GDP per hour worked is 27.)

As it happens, Basu also appears to be unaware that Argentina now has one of the most open immigration policies of any country in the world. It is all laid out here. It is pretty easy to migrate lawfully and as for those who arrive unlawfully there is no discrimination re the provision of things like health and education services, and it seems that you have to do something really rather bad to be deported, and the government is keen to offer opportunities to illegal migrants to regularise their status (and stay). As the open borders advocates who wrote the description note

“Argentina does not have truly open borders, but it comes remarkably close”.

This regime has been in place for 15 years now.

And yet very few people migrate to Argentina. An OECD study last year looked at the role of immigration in Argentina, but noted

The number and characteristics of immigrants in Argentina suggest that their current economic impact is positive, but not large. As immigrants represent less than 5% of the population, their role in the country’s economy is certainly less pronounced than it was during the first half of the 20th century.

Net migration to Argentina remains exceedingly low. I’m not sure why – there are worse places in the world – but a reasonable hypothesis might be that migrants flock towards success (which is a pretty sensible approach for them and their families) rather than being determinative of that success. Argentina hasn’t found the model of economic success. (It is an interesting question why, say, economic migrants from Africa don’t try Argentina, but then one might reasonably wonder whether the liberal approach (whether to residence or welfare entitlements) would last long if there really were such a substantial influx.)

One could take various tacks from here. One could illustrate the way most – but not all – of the more successful economies in the last century haven’t been ones that consistently encouraged large-scale immigration. Or that flat or even falling populations and/or absence of much immigration, don’t seem to have held back the various countries (from South Korea, Malaysia, the Baltics, Romania, Chile, Uruguay that 15 years ago had similar average levels of productivity to Argentina – of those countries, only Venezuela and Mexico have done worse than Argentina. Even Russia – also similar average productivity- has done better.

And there are various other questionable bits in Basu article – eg he seems to be championing holding up global interest rates. But I think I’ll leave the article here. There is much to dislike about Trump, much to worry about in the wider world, but the economics behind the claim that the US is at risk of heading Argentina’s way just don’t seem to stack up.

He’s just reflecting the political biases of the Davos “bubble” crowd.

He’s swimming against the tide. His model has delivered gains, but those gains have been captured by the political elites and not widely shared while the middle class in every developed country – including ours – is under tremendous pressure.

LikeLike

I came from Argentina nine years ago being 40 yo. I can tell you immigration has nothing to do with Argentina’s decline, all to do with a turn towards socialist policies (instead of continuing with liberal/capitalist principles).

Long story short: Argentina’s Constitution follows the liberal lines of the American one (main contributor was J. Bautista Alberdi, google it). For the first few decades, that combined with wealth in natural resources got Argentina on the right path.

Towards mid-twenty century (1930-40) the country got into the fascist bandwagon (J. D. Peron following Mussolini’s ideas and closely associated to Franco in Spain. Again, google it). There is a reason why all the nazi’s took refuge down there, you know….

Unlike Germany, Spain or Italy, there was no war to lose or win. No close up, and up to this day the mainstream line of thought for the entire country still goes along the lines of “daddy State and an Strong Leader must look after us”.

The rest is, literally, history.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Thanks

LikeLike

Thanks for your post. New Zealanders also have an enthusiasm for authoritarian leaders, like RD Muldoon who ran the country like an antipodean East Germany. Large scale, low skilled immigration of the kind New Zealand has run for a decade or so makes us all poorer, creating an enormous burden on infrastructure and services. As for Trump, America remains a beacon on a hill whatever you think of them.

LikeLiked by 3 people

All look at the easy of doing business data its very tough to start and build a small business.

LikeLike

I have a friend who had to abandon her attempt to live in Argentina after several years because it was impossible to get her student visa. The bureaucracy was incompetent, lazy and unaccountable. It may theoretically be a near open border but in practice it isn’t. Of course it is possible she just didn’t know how to navigate the corruption.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not a fan on any account of Trump? He has been the only president to follow the US law and put the US embassy in Jerusalem and recognise Israel’s three thousand year history. He has worked very closely with Christian groups to help black Americans find work when they come out of prison and has managed a 80% non re-offend figure. This is amazing having worked as a prison chaplain for 5 years in US prisons. I think you must have gained your impression of Trump from fake media sources not from factual actions of the president.

LikeLike

As with almost any President or Prime Minister there are things Trump has done that I support, or even enthusiastically endorse. I’d put the move of the embassy to Jerusalem and judges in that class, and the little of what I know on the prison front. That doesn’t change my view – expressed before he was elected when I was clear that were I American I’d not vote for either Clinton or Trump – that he is unfit – by temperament and character, and several revealed actions since – to be President of the United States. Character matters.

LikeLike