I was flicking through the annual fiscal numbers released earlier this week and really only a couple of things caught my eye.

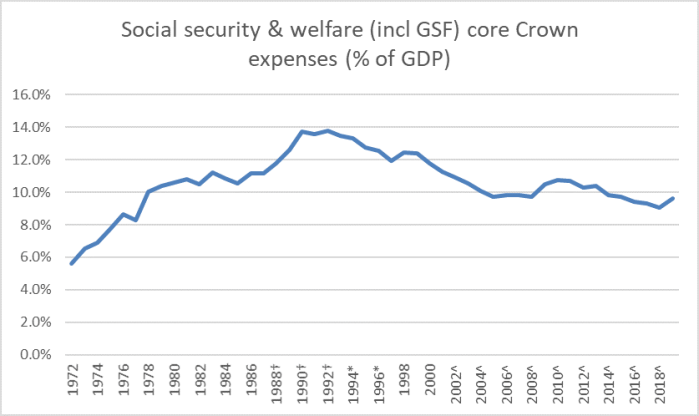

The first was welfare spending. Here is the long-term chart from The Treasury’s data showing annual spending as a share of GDP back to 1972.

The big trends – up to around 1992, down since – are pretty striking. So too is the fact that we now spend almost twice the share of GDP on welfare as we did in 1972 (by contrast, education spending as a share of GDP was exactly the same in 1972 as in 2019).

But what mostly caught my eye was that last observation – quite a substantial tick up from 9.0 per cent in the year to June 2018 to 9.6 per cent in the year to June 2019. Welfare spending does go up some years – and has done even in face of the declining trend since the early 1990s – but it usually does so when the economy isn’t doing well and the unemployment rate is rising.

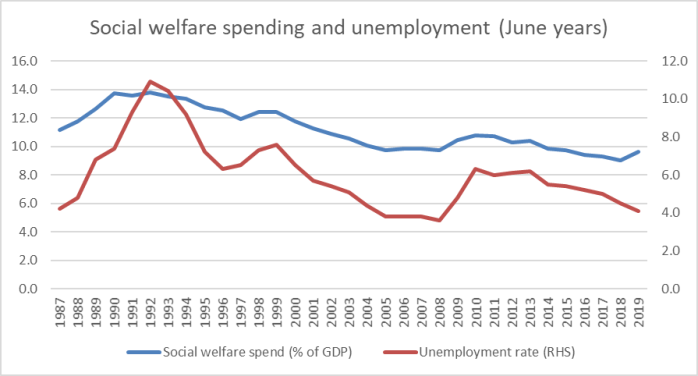

The three previous episodes in which welfare spending rose as a share of GDP (late 80s to 1992, late 90s, and over the last recession) were also episodes in which the unemployment rate was rising. You’d expect that sort of relationship; not only will there be more people on the unemployment benefit (whatever they call it these days) but people on other benefits will also find it harder to get off and into work.

By contrast, in the latest year, welfare spending rose (considerably) as a share of GDP even though the average unemployment rate fell quite a bit during that year.

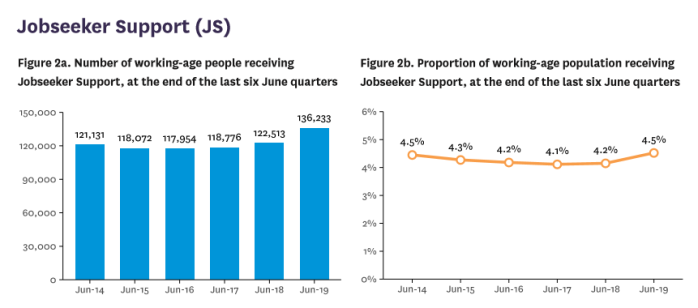

Despite that fall in the official unemployment rate, the number of people getting a benefit as a jobseeker increased a lot.

There has been no suggestion from the government that they don’t believe the HLFS and really the unemployment was rising over their first full year in offfice.

The new government has chosen to spend a lot more money on (certain classes of) welfare beneficiaries. And, thus, to many the increase will probably look like a “good thing”. Count me rather more sceptical. I think there are some categories of welfare recipients who are poorly treated by the system and to whom society should be rather more generous. But, for example, the Accommodation Supplement is now costing well over $1 billion dollars per annum (0.3 to 0.4 per cent of GDP) and yet with better government choices, rents should have fallen a lot in real terms and decent housing been cheaper than ever. And the cost (per cent of GDP) of NZS keeps rising even year, with unchanged parameters even as life expectancies increase. (In the longer-term, a stronger cultural emphasis on marriage might even reduce the number – 60000 – of solo parents receiving benefits.) Perhaps our culture and society are so far gone that we can’t readily get back to 1972 when “only” 5.6 per cent of GDP was being spent on welfare – in a pretty comprehensive welfare system – but it isn’t obvious why we couldn’t be both humane and firm without heading back towards spending 10 per cent of GDP on welfare.

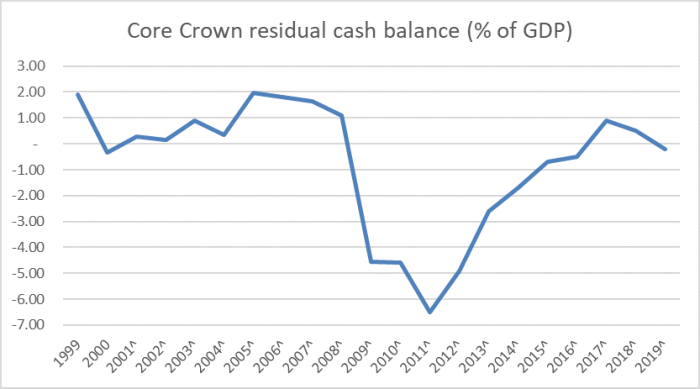

The other series that caught my eye was that for the “core Crown residual cash” balance. It doesn’t get a lot of attention, although a sage Treasury official once encouraged me to pay more attention to it than is perhaps customary.

It isn’t a perfect indicator either – anything can be gamed – but it is a reminder that the government isn’t exactly awash with cash. In fact, on this measure there was a modest deficit (0.2 per cent of GDP) last year. This year’s Budget projected the deficit to widen a bit further in 2019/20. In itself, that is nothing to be alarmed about, but it is a rather different situation than we were in in, say, 1999 or the period from 2005 to 2007.

One can mount an argument – which I’m sympathetic to – that this balance probably should run in modest deficit in normal times, at least while we continue with our bipartisan immigration policy insanity, that generates such rates of population growth. With a strongly population population, you would expect cash outflows associated with capital expenditure to be quite high, without jeopardising fiscal health. Modest residual cash deficits will be consistent over time with modest levels of public debt as a share of GDP. Some support that, although I’m more persuaded by the case for something more like what we have now – general government net financial liabilities of basically zero per cent of GDP (our governments try to hide this by using net debt measures that exclude the big pool of financial assets managed by the New Zealand Superannuation Fund).

I remain somewhat ambivalent at best about the case for larger deficits and/or higher government spending. Of course, were I a died-in-the-wool Labour (or Greens) voter I might wonder why my left-wing government was really only spending about as much (per cent of GDP) as the previous National government. But setting that to one side, the terms of trade have been high and we can’t count on them staying up indefinitely. I’m sceptical that the unemployment rate is yet at or below the NAIRU, but if a recession were to hit in the next few years, it would mean quite a loss of revenue at least temporarily. And the evidence that governments are spending wisely, at the margin, on either capital or current proposals is already pretty slim. I can see a case for increased health spending, for example, but wasted spending such as fees-free for tertiary education, doing nothing about the NZS age of eligibility (or years residence required to receive it), or the PGF don’t convince me that there is any pressing case for materially higher spending in total, as distinct from a more rigorous reprioritisation. Waste is waste.

And on the revenue side, the tax rates facing businesses (especially foreign investors) looking to invest in New Zealand are among the highest in the OECD.

Of course, the limits of conventional monetary policy are approaching. I’m not persuaded by, on the one hand, some local banks suggesting there is no point taking the OCR below about 0.25 per cent – I reckon there is a full percentage point usefully on offer beyond that – or, on the other hand by international reports from central banks (including from the BIS/CGFS this week) sounding complacent about (eg) asset purchases can do, but there is action central banks and governments can take to give themselves more monetary policy leeway, making the effective lower bound on nominal interest rates materially less constraining. It is a mystery to me why they show no sign of taking that option seriously.

On the fiscal front, I am somewhat attracted to the notion of a temporary reduction in GST as a stabilising instrument in a recession. The Herald’s Brian Fallow has recently been championing this idea, and it was argued for here a decade or more ago as a potential tool by prominent UK/Dutch economist Willem Buiter. The UK actually did it in the last recession. GST cuts can be implemented pretty quickly, and directly affect both the absolute price of consumption now, and the relative price (making consumption more attractive now relative to the future). It isn’t a foolproof instrument – they don’t exist – but I was a little surprised to learn that Grant Robertson appeared not to regard it as an option worth his officials exploring. I guess IRD would hate the idea, but that isn’t good grounds to ignore it as a potential fiscal option.

What about infrastructure spending?

LikeLike

In principle it sounds like a good idea, but (a) governments have a poor track record of doing high-value infrastructure projects (eg Transmission Gully that failed cost-benefit tests when it was approved, the East-West Link in Akld the prev govt tried to do, the City LInk project in Akld, and all manner of rail and cycle projects, and (b) which matters a lot for countercylical purposes, there are inevitably long lead times for any significant project (some regulatory, others just practical) which means it is hard to get demand boosted at the period when the economy is weakest.

By contrast, mon pol works quickly (as, probably, would be variety of fiscal transfer measures or a GST change).

LikeLike

The problem with mon pol is that our RBNZ since Don Brash has got no idea how it works. There was this rather nonsense thinking that lower interest rates increase NZ household consumption and higher interest rates dampen NZ household consumption. With NZ household savings almost equal to NZ household borrowings this assumption is simply not correct. Simple maths would have told you the RBNZ was completely wrong.

LikeLike

Foreign Investors and tax rates

I used to trawl through the monthly OIO approvals and decisions. Found them interesting. Gave up a couple of years ago. Just went and had a look today. They’re still active. Haven’t eased off much. Quiet in September 2019, but go through prior months and years. Tax doesn’t seem to be a disincentive. It’s all there

https://www.linz.govt.nz/overseas-investment/decision-summaries-statistics

LikeLike

What do you make of this Michael

https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2019-10-10/inequality-globalization-and-the-missteps-of-1990s-economics

LikeLike

I’m told the Auckland Harbour Bridge had a BCR of 0.4 or something; which if you follow your logic would mean we wouldn’t have built it. Not sure there’d be many takers for that. My prediction is TG will open and it will be transformative; in the same way Waterview has been and the CRL will be as well.

LikeLike

Hard to engage on an “I’m told” – esp as the Harbour Bridge was tolled from the start – but often timing matters. A project that may not make econ sense now may make sense in five years time. Money has value, in alternative uses, in the meantime.

Incidentally, Waterview would have been a much better econ proposition as a gully not a tunnel.

LikeLike