The Reserve Bank Governor has been heard in recent months expressing concern about the possibility that inflation expectations – what people think will happen, which in turn can influence how they act – will drift lower. It might seem like a rather abstract concern, but there are real world consequences. If everyone used to expect inflation would be 5 per cent and now expect it to be 2 per cent then, all else equal, nominal interest rates will have to be set 3 percentage points lower than previously just to get the same degree of monetary policy bite/stimulus. All else equal, if inflation expectations – the ones that genuine reflect behaviour – are falling then real interest rates are rising.

Lower inflation expectations has been the trend in New Zealand for more than a decade now. The Reserve Bank surveys households and perceptions of the current inflation rate and expectations of the future inflation rate are both quite a lot lower than they were prior to the last recession. Term deposit rates are now perhaps 500 basis points lower than they were in 2007, but in real terms that reduction is perhaps no more than 300 to 350 basis points. On the more-widely quoted survey the Bank does of somewhat-more-expert observers, medium-term inflation expectations are also about a full percentage point less than they were in 2007. In those days we took as pretty normal inflation of around 2.5 per cent. No one – try some introspection on yourself – thinks of that as a normal New Zealand inflation rate now.

Some of that reduction in inflation expectations hasn’t been unwelcome. The Reserve Bank had tended to be rather too accommodating of inflation in in the top half of the target range (some mix of forecasting mistakes and a cast of mind that wasn’t too bothered) and the range itself had been pulled up a couple of times by governments. Expectations – of the sort that shape behaviour – genuinely centred on the target midpoint, 2 per cent inflation, would be a “good thing”. More recently, across the range of surveys, expectations look to have been drifting down again. With nominal interest rates already so low, that isn’t a good thing. For example, when one thinks of the extent of Reserve Bank OCR cuts this year, the moves look quite large : 75 basis points.

But here are the three retail interest rate series the Reserve Bank publishes, showing the changes since the end of last year (and December last year wasn’t some abnormal month, but roughly where rates had been all last year).

SME new overdraft rate -37 basis points

New residential first mortgage rate -59 basis points

Six month term deposit rate -47 basis points

Deduct say 15 or 20 points more for a decline in inflation expectations and you really aren’t looking at much of a decline in real short-term interest rates (facing firms and households) at all. By contrast, a 20 year indexed government bond rate (ie a very long term real interest rate) – set freely in the market – has fallen by about 120 basis points.

What is striking about the Reserve Bank’s treatment of inflation expectations is that they hardly ever – change the Governor, change the chief economist and still they choose to ignore it – refer to the market-based indicator of implied inflation expectations from the market for government bonds. There are all sort of quibbles people can mount about the numbers, but the fact remains that it is the only market-based measure, reflecting actual choices and dollars, not just answers to a survey question.

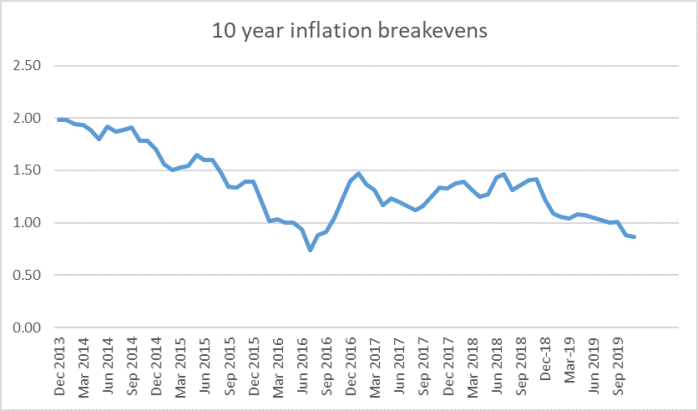

Here are latest inflation breakevens for New Zealand: the gap between the 10 year nominal government bond rate and a 10 year real government bond rate (linearly interpolated from the yields on 2025 and 2030 inflation-indexed government bond rates). The last observation is the chart is yesterday’s data.

It is old news that the last time these “breakevens” or implied inflation expectations were last at 2 per cent almost six year ago. Not since then have financial markets been trading as if they believe the Reserve Bank will do its job over the coming 10 years. This measure of expectations fell away sharply over 2014 to mid 2016, when the Bank was messing things up – tightening when no tightening was necessary and then being grudging in their cuts (as Wheeler became ever more defensive). There was something of a rebound, but it hasn’t lasted and since the end of last year the breakevens have been dropping away again. Right now, markets are trading as if the average inflation rate over the next ten years could be as low as 0.87 per cent. The OCR cuts this year have not been enough to stabilise, let alone reverse, the series.

Some of the patterns are global. Here is the comparable US series

But the levels are national. If current US breakevens should be uncomfortable for the Fed, at around 1.5 per cent they should be nothing like as troubling as the 0.9 per cent we have in New Zealand. And, for once, going into any serious downturn our central bank has less conventional monetary policy leeway than the Fed does.

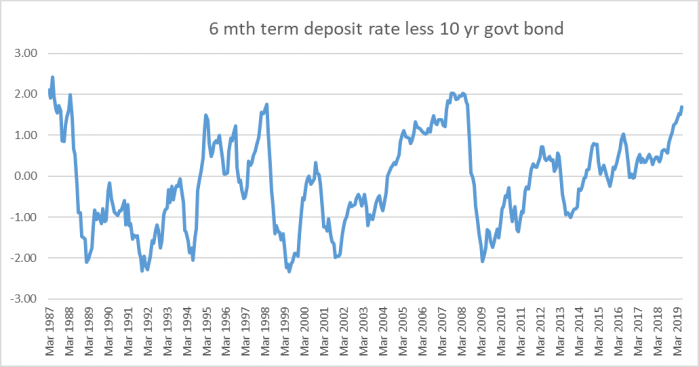

Throw in the slope of the yield curve – this chart from a few weeks ago, in which each time this variable has been at current levels it has been followed by a recession – and there is a pretty good case for the Reserve Bank doing more than it has done.

Inflation expectations have already been falling. Given how little conventional policy room most central banks have – and the distinct limits of unconventional policies – if there were to be a recession (here and/or abroad), few people then would rationally expect monetary policy to do its usual work. A rational response would be for inflation expectations to fall away quite a bit further, driving real interest rates up (all else equal) at a time when the capacity for further nominal interest rate cuts is all but gone (unless/until governments finally do something about the effective lower bound). That really would be a bad outcome.

In putting together this post, my eye was drawn to the array of current nominal New Zealand interest rates – for any term at all now less than 1 per cent. Here are some comparisons across a range of dates (12 years ago was in the months prior to the last recession – and for anyone interested 30 years ago all the rates were in double figures).

| Conventional government bonds | |||||

| 90 day bill | 1 year | 2 year | 5 year | 10 year | |

| 22 years ago | 7.63 | 7.33 | 6.75 | 6.61 | 6.59 |

| 20 years ago | 5.00 | 5.55 | 6.14 | 6.78 | 7.06 |

| 12 years ago | 8.75 | 7.04 | 6.98 | 6.70 | 6.28 |

| 10 years ago | 2.77 | 4.15 | 4.91 | 5.56 | |

| Five years ago | 3.68 | 3.50 | 3.98 | 4.06 | |

| Current | 1.04 | 0.78 | 0.69 | 0.76 | 0.99 |

Perhaps what is easy to lose sight of is that the steepest fall in New Zealand long-term actual and expected interest rates wasn’t in the wake of the last recession, but in the last five years (when our political parties squabbled over an allegedly healthy economy).

Whatever the Governor claims, these extraordinarily low interest rates are not normal by any standard, recent or historical. And yet, at very least, they are necessary and unavoidable, in response to all else – public and private – going on in national and international economies.

Low inflation over the decades also coincides with China increasing its dominance on the production volume and pricing of global consumer products for all the top brands. I just upgraded my Iphone 6 to a Huawei P30 Pro, 256GB which has 4 cameras and a AI. This was released more than a year ago at $1499. The price now is $1049 and includes a $350 watch with a Vodafone term contract. The newly released equivalent Iphone 11 Pro with 256GB with 4 cameras and AI costs $2,249.

Even though both phones are manufactured in China the prices differ considerably due largely to a brand differentiation rather than anything technical. The lower margins due to the higher volumes given the size of the Chinese consumer market it puts a downward spiral on prices.

LikeLike

The seventies were a time of new technology at ever cheaper prices made in Japan. I remember going to university in ’68 with my first ever purchase – a Japanese made transistor radio. But high inflation. I cannot make any sense out of economics.

LikeLike

The main distinction is that Japanese companies did not invite massive Western capital into its manufacturing in Japan nor did it want to integrate with western supply chains.

China has aggressively integrated into global supply chains as an important part of its growth strategy affecting all the major brands and manufacturing production throughout the world. Big difference between the Japanese model and the Chinese model.

LikeLike

Japan has 123 million people and China has 1.4 billion people. The market size difference is more than 10 times. A company in China needs only $1 margin in its pricing to be a billion dollar turnover company. In Japan to be of a similar size that company must charge a higher $10 margin to be a billion dollar company.

An aggressive competitor from China with a large domestic market will beat down any other global competitor. Simple maths. Yes disposable income in China is low but it is growing. It is that growing middle class that allows Chinese companies to price aggressively.

LikeLike

Does seem to beg the question: “whose” inflation expectations matter most? (market vs. business owner vs. consumer). And I guess with stable nominal wages, real wages have been rising and the current account trend doesn’t scream of demand being deferred. The inflation process, a riddle.

LikeLike

Yes, and add to the “whose” question, questions about whether surveys really capture the numbers people implicitly behave on. I suspect the expectations of many different groups matter, mostly around the response to particular nominal interest rates, but also – and to some extent – in wage setting.

LikeLike

I am in conversations every week where people are wondering about where to invest and I am in in the banking/investment industry. People are already hearing and seeing the overseas experience of even lower interest rates and are implicitly starting to build an expectation.

LikeLike

Thanks for this. One question of detail: should the second “nominal” in the para above the “10 year inflation breakevens” chart be “real”?

LikeLike

Thanks. Well-spotted (and now corrected)

LikeLike

Hmm it looks like your website ate my first comment (it was extremely long) so I guess I’ll just sum it

up what I had written and say, I’m thoroughly enjoying your blog.

I as well am an aspiring blog writer but I’m still new to everything.

Do you have any tips and hints for rookie blog writers?

I’d genuinely appreciate it. – Calator prin Romania

LikeLike

Thanks. I guess my only advice is (a) the best way to develop your writing is to write, and (b) write about what interests you – I’m glad I’ve found an audience, but I wouldn’t have kept going if what I was writing didn’t matter to me.

LikeLike