On Wednesday afternoon the Reserve Bank Monetary Policy Committee released their latest OCR decision. It was, as predicted, no change in the OCR. I don’t think it was the right decision on the substance (some background to that here) but at least it was in line with the Governor’s public comments following the previous surprise decision.

I didn’t have that much to say about the two pages (statement plus “minutes”) they released. So just a few quick points:

- in the statement the Bank continues to overstate the contribution of the “trade war” to the slowdown in global trade and global growth. It is a convenient “newspaper headlines” story, but the way they use it suggests they haven’t thought much more deeply about the issues,

- they talk up the prospects of economic recovery, based on the reduction in interest rates, but never seem to recognise that interest rates had been cut for a reason. Unless the OCR is cut by more than any fall-away in economic fundamentals, you wouldn’t expect to see a rebound. As I pointed out last week, actual cuts in variable retail rates lag well behind the fall in market-determined long-term rates,

- there is something inappropriate about the Bank talking up the idea of fiscal stimulus three times in two pages (not that fiscal stimulus might be out of place in some circumstances, but it is entirely a matter for the elected government). On the other hand, I guess we should be grateful that the Governor has stepped away from his August comment that “of course the government has to be spending more”.

- it is interesting that, at least as written, the MPC appears not to have any bias on the direction of the next move in the OCR. They are very widely expected to cut in November and cut again next year but there is nothing in this statement to lead one to think the MPC shares that view – if anything, in the minutes we read that “some members”, with a cost-plus model of inflation apparently, believe there is “potential for rising labour and import costs to pass through to inflation more substantially over the medium-term”. Their predecessors were hawking similar lines in 2015/16.

It is 18 months today since Adrian Orr took office at Governor of the Reserve Bank. I’ve not infrequently bemoaned the fact that in that time Orr has not given a single substantive on-the-record speech on monetary policy or banking regulation/financial stability (the Bank’s two main areas of responsibility). Yesterday Orr gave short speech to a corporate audience in Auckland, which dealt with both monetary policy and (in more abbreviated form) banking regulation. I guess we should be thankful for small mercies.

Sadly, the contents of the speech suggest we have a Governor who simply makes stuff up whenever it suits him. It is extraordinary in such a powerful public figure, one supposedly operating as an independent and judicious technical expert. Much of it comes across as almost delusional – perhaps welcome to his mates in the Beehive, but even they must sometimes wonder whether independent public institutions aren’t meant to be more than cheerleaders.

To take just a few examples of what I have in mind, start here

The good news for New Zealand, unlike many other OECD economies, is that our government’s books are in good shape and there is already a strong fiscal impulse underway from public spending and investment.

There is no disputing the first half of the sentence. It is to the credit of successive governments of both parties that government debt has been kept pretty low and stable over recent decades. But what about that second claim, about the “strong fiscal impulse”? Well, it simply isn’t supported by the facts at all. This is from my post on last month’s Monetary Policy Statement when the Governor tried to run the same sort of line.

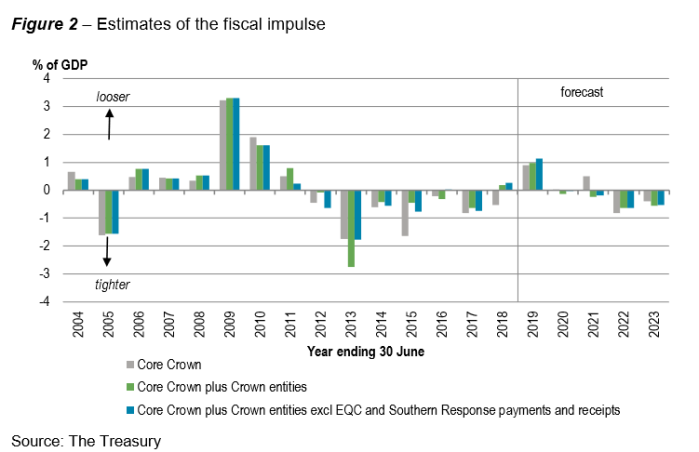

In fact, it prompted the perfectly reasonable question from Bernard Hickey about whether fiscal policy was actually very stimulatory at all. The standard reference here is The Treasury’s fiscal impulse measure. This is the chart from the Budget documents

It isn’t a perfect measure by any means, and in particular one can argue about some of the historical numbers. In my experience, it is a pretty useful encapsulation of the fiscal impulse (boost to demand) for the forecast period. In fact, the measure was originally developed for the Reserve Bank – which wanted to know how best to translate published forecast plans into estimated effects on domestic demand/activity.

And what do we see. There was a moderately significant fiscal impulse in the year to June 2019. That year ended six weeks ago. For current and next June years, the net fiscal impulse is about zero, and beyond that – which doesn’t mean much at this stage – the impulse is moderately negative. All using the government’s own budget numbers. And consistent with this, operating revenue in 2023 is projected to be higher as a share of GDP than it is now, and operating expenses are projected to be lower (share of GDP) than they are now. The Budget is projected to be in (fairly modest) surplus throughout.

And yet challenged on this, the Governor seemed to be just making things up when he claimed that we had a “very pro-active fiscal authority” and that “the foot is on the fiscal accelerator”. It just isn’t. Orr must know that (after all, he had Treasury’s Deputy Secretary for macro sitting as an observer in this MPS round). One even felt a little sorry for the Bank’s chief economist spluttering to try to square the circle, but basically acknowledging that Hickey’s story was right, not the Governor’s. Perhaps, you might wonder, the Bank thinks the fiscal impulse measure is materially misleading and has its own alternative analysis of the government’s announced fiscal plans. But that can’t be so either: there is no discussion of the issue in the Monetary Policy Statement.

(Incidentally, on Morning Report this morning Grant Robertson tried the same sort of line, only for the presenter to point out to him the fiscal impulse measure, reducing the Minister to spluttering “but we are spending more than the last lot”. That is true, but the material overall fiscal boost was last year – and growth and activity were insipid even then, inflation still undershooting the target.)

Was he being deliberately dishonest or simply making stuff up as he went protraying things as he’d like them to be? You can be the judge, but neither alternative puts our central bank Governor in a good light.

Given that he has since had another 7 weeks to get his lines straight and yet repeats the same line, it looks even worse for him now. As I said last month, if the Bank has an alternative take on the demand implications of fiscal policy it surely behooves them to lay it out for scrutiny, not just make idle claims inconsistent with their longstanding standard reference source the Treasury estimates).

Just as preposterous was this claim from the Governor

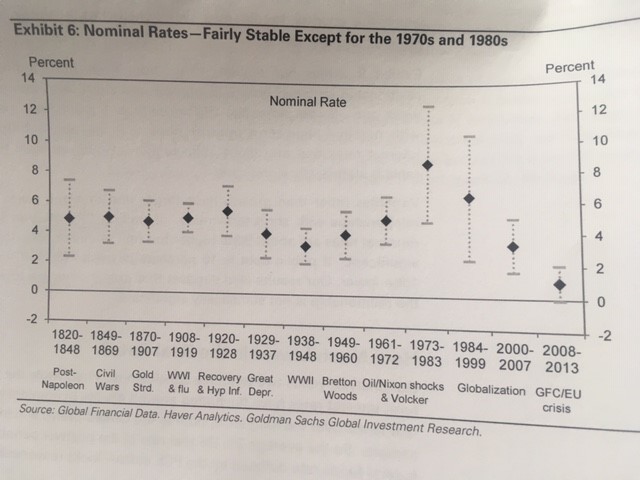

The low level of interest rates globally over recent years primarily reflects low and stable inflation rates – a deliberate and desired outcome of monetary policy.

Here the Governor was repeating much the same nonsense it is reported that he ran to Parliament last month

Over the weekend, I came across an account of the Governor’s appearance on Thursday before Parliament’s Finance and Expenditure Committee to talk about the Monetary Policy Statement and the interest rate decision. …. The Governor was reported as suggesting although neutral interest rates had dropped to a very low level, that MPs should be not too concerned as we are now simply back to the levels seen prior to the decades of high inflation in the 1970s and 1980s.

I’m not going to repeat the entire post I devoted to illustrating just how unusual global (and New Zealand) interest rates now are, both in nominal terms and (even more so in the long sweep of history) on real terms. In centuries past there was little or no rational expectation of sustained inflation, while these days everyone agrees that medium to long-term inflation expectations are somewhere between 1 and 2 per cent. The Governor may also have forgotten, in a New Zealand context, that the inflation target here is now materially higher than it was, say, 25 years ago. Interest rates are, of course, far lower. Here is just one chart from the earlier post, showing how unusual global interest rates were even five years ago (things are still more anomalous now, especially here).

As a final chart for now, here is another one from the old Goldman Sachs research note

In this chart, the authors aggregated data on 20 countries. Through all the ups and downs of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century – when expected inflation mostly wasn’t a thing – nominal interest rates across this wide range of countries averaged well above what we experience in almost every advanced country now.

Why does the Governor say this stuff? Does he have no advisers left who are willing to tell him that what he says just isn’t so?

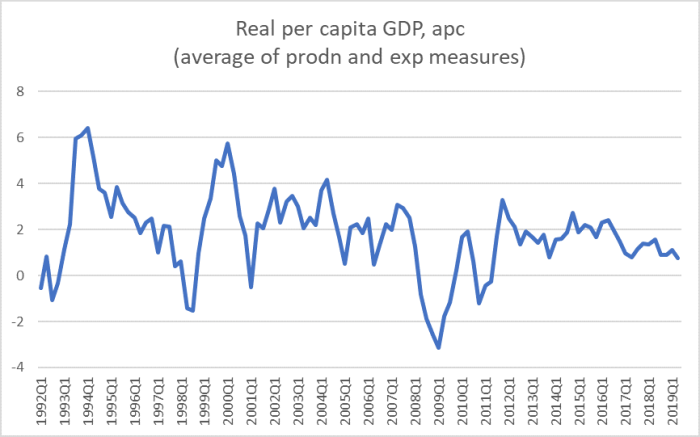

There are claims that the domestic economy still has “ongoing momentum” and that there is “strong demand for goods and services”. These claims appear to be based the Governor’s interpretation of comments from the small group of firms the Bank went and visited recently. Never mind the economywide measures, whether the range of business confidence and activity measures, or…..well, the national accounts.

He goes on repeatedly about how interest rates make it a great time to invest, as if he’d not given a thought to possible reasons why interest rates might be low (NB, it isn’t just because inflation came down again, see above). He claims we have a “great environment to invest”, talks of “low hurdle rates for investing”, but seems not to recognise that in a climate of uncertainty, whether around policy (here or abroad) or the economic outlook, the option of simply waiting has considerable value, or thus that there is little reason to suppose that hurdle rates for investing have dropped much, if at all, in more recent times.

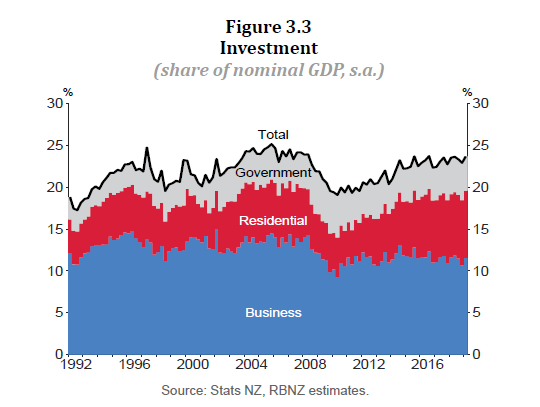

As a bureaucrat Orr is apparently convinced it is a great opportunity to invest and that profitable investment opportunities abound. Experience suggests that people with a bottom line to meet disagree with him. Here is the Bank’s own chart from the most recent MPS showing business investment as a share of GDP, with a few observations from me.

As I’ve noted here repeatedly, business investment never recovered strongly from the last recession, and if anything (as share of GDP) has been falling back again in the last few years, even as population growth remained strong.

But despite the feeble business investment performance, the Bank expects business investment to recover from here. There is no hint as to why they believe that is likely…. If there is any basis for their beliefs it seems to be little more than the repeated claim by the Governor and the Minister that it is “a great time to invest” in New Zealand. But firms didn’t think so over the last five years – even with unexpected population shocks – and surely the reason the Bank is cutting the OCR has quite a bit to do with deteriorating conditions and investment prospects here and abroad?

But what do firms know?

Orr seems to more or less acknowledge the uncertainty issue, in these strange sentences, tinged with corporatist sentiments

However, there remains a loud call from all quarters of the country for leaders to better signal investment intent, and ensure we have the policy and goodwill to facilitate access to capital and resources to execute.

This call for investment-intent is to all collectively-owned (e.g., Iwi), Crown-owned (i.e., central and local government), and co-operatively owned (e.g., traditional primary sector) sectors. It is not just to traditional businesses, or any one party.

Easily said, harder to do without a clear desire to work together over an agreed horizon.

Or he could just have mentioned the major policy uncertainties. Whatever your view on the merits of any of these issues (and I’m steering clear of expressing such views) mightn’t you think that uncertainty around the ETS, water quality policy, highly productive lands policy, the future of the RMA itself, whether any more significant roads will be built by a government apparently averse to them, bank capital regimes, the future of extractive industries might all be among the sorts of factors that might leave businesses and potential investors just a little wary, and pricing that uncertainty into their decisions around investment?

It all comes to a climax in this extraordinary claim in the Governor’s final paragraph (emphasis added).

In summary, we are not alone in the low interest rate environment, this is a global phenomenon. However, what we do have is more policy and business opportunities than most OECD economies and this is something that we need to take advantage of.

If by that he means that New Zealand productivity and per capita income rank far behind most of the OECD countries we used to like to compare ourselves to and that, at least in principle, those gaps could be closed, then I’m right with him. But absolutely nothing about how policy has been run by successive governments for at least 25 years now has (so it appears from the evidence of hindsight) been consistent with closing those gaps: the productivity gaps in particular have just kept on widening and (though you would never know it from the Governor’s speech) we’ve had little or no productivity growth at all for the last five or more years. Nothing about current policy suggests that record will improve in the next five years, and if anything one could mount a plausible argument that the measures adopted by the current government are heightening the risk of even worse (relative performance outcomes) in the next five. Not only is this stuff well outside the Governor’s area of responsibility – which is about macro and financial stabilisation – but he either just doesn’t know what he is talking up or knowing better he just mouths such platitudes anyway.

Finally, there are several paragraphs in the speech about the Governor’s proposals to hugely increase the amount of capital locally-incorporated banks will need to have to back current balance sheets. Notionally, there is process of consultation and deliberation going on at present. But when you read from the sole decisionmaker words like these,

Our proposals would see significant increases in shareholder capital in banks. With banks having more of their own ‘skin in the game’, the owners will sharpen their long-term customer focus, and it will reduce the chance of a bank failure and the cost on society as a whole should a bank fail. These outcomes are highly desirable for the long-term economic health of New Zealand, and should promote deeper and more liquid local equity and debt markets.

We finalise our decisions in early-December this year. Whatever our final decisions, we will be insisting on transition to higher capital at a sensible pace.

with all those “will”s, you get a pretty strong sense of pre-judgement. That is, of course, what you’d expect when those proposals were based on very weak analysis – numbers plucked out of the air at the last minute – and when the Governor is prosecutor, judge, and jury in his own case, and where he knows that there are no effective appeal rights against his verdict as unelected unaccountable decisionmaker.

It really isn’t good enough. Citizens should expect better. The Bank’s Board is paid to hold the Governor to account, but they are almost worse than useless (they provide shadow without substance, suggesting there is scrutiny and accountability when there isn’t). If the Minister of Finance were doing his job, or Parliament’s Finance and Expenditure Committee was doing its job, some pretty hard questions would be being asked about just what is going wrong at the Bank, and how such shallow – and frankly embarrassing – material is emerging from the mouth of such a powerful public figure.

Instead, no doubt, things will continue to drift, and the slow decline of New Zealand’s economic institutions – hand in hand with the continuing decline in New Zealand’s relative economic performance – will continue.

But, you businesses out there really should be investing. This Governor tells you so.

I know that you do not believe that compliance costs are a major deferent to business investment but if I could just give you one small example. I am not certain I have all the facts correct but as I understand it a Company dry hired a bus to a qualified driver. The driver had an injury accident. Work safe took the the hire company to court and the hire comany had to pay about $750,000. Remember in these cases the business owners can be personably liable. As a small business owner rulings such as these can not only keep you awake at night but do not encourage you to invest and expand a business.

LikeLike

Thanks for that example. To be clear, my only scepticism is that compliance costs etc go far in explaining wht productivity etc is so much worse than in other countries, because most other advanced countries also have lots of burdensome business regs, compliance cost problems etc. In an absolute sense, I quite see that they are an issue (even among managers in the public sector confronting personal liab for operational decisions and accidents they are involved with or have some responsibility for).

LikeLike

Most advanced countries have a lot more factories than we do. Our economists just wrongly thought cows was highly productive because it does not count people and negligently forgetting to count the cows. Unfortunately our government took advice from economists and turned all its taxpayer funds towards think big farming with the likes of Landcorp ie government buying farms where it makes no sense for the government to be in farming.

The annual $400 million in Treaty of Waitangi settlements also mostly gets re-invested into farming assets by Maori Iwi.

LikeLike

The problem with burdensome compliance in NZ is that it breeds professional contractors whose entire jobs are to delay businesses from getting things done. In other corrupted countries when you pay a bribe it greases the wheels of compliance and make things go faster. In our case, we pay legal professional fees which is in essence also a bribe but that legal bribe just slows things down.

LikeLike

A strikingly poor performance

Fonterra Co-operative Group Limited is/was NZ’s largest company

Fonterra Co-operative Group Ltd is a NZ multinational dairy co-op owned by around 10,500 NZ farmers

Valued at $9 billion just two years ago, it is now valued at $5 billion

It won’t be investing much of anything in the immediate future

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Michael. Recognise your point. From my perspective given the distance from markets and lack of economies of scale we need to minimise compliance costs to try to have some competitive advantage.

LikeLike

Distance from markets have never been a problem for importers. Why should it be a problem for exporters?. Economists just keep pointing at red herrings and expect solutions. Agree completely with economies of scale. Larger market equates to higher volumes at lower margins. It is the lack of a large domestic market that prevents us from exporting product at a competitive price not distance.

LikeLike

Fonterra

Ansett

BNZ

etc etc

We are really good at destroying value.

LikeLike

The main problem is expansion. We tend to hire international CEOs to expand our businesses once we have reached peak market share in NZ. The problem with international managers is they go for volume at lower margins because they have been trained in large markets. In NZ it is about higher margin rather than higher volume due to our small market.

LikeLike

When we expand offshore it is a tough balancing act between having NZ managers who are great at market share preservation and growing margin with international managers who are good at growing market share growing volume but at the expense of lower margins. If new market penetration and higher volume is not fast enough when sacrificing margins those companies would then suffer dramatically.

LikeLike

I’m still trying to recover from his urging of indebted citizens to borrow more. We are saddled with a lame duck Treasury and a Governor that seems to have lost the purpose of his role.

LikeLiked by 1 person

All abetted by a government that doesn’t care.

LikeLike

“If the Minister of Finance were doing his job”? He is incapable of doing his job. He has no understanding of finance or the economy. Robertson’s appointment was the equivalent of Caligula making his horse a consul. When the heat really comes on he will dive for cover. Orr is simply a shill for government by incompetents.

LikeLike

What has impressed me is that under Adrian Orr’s watch the giant Chinese banks have started to compete, with the Bank of China and the China Construction bank dropping interest rates to a worthwhile challenge of 3.19% against our Australian monopoly banks offering 3.45% and falling. I had thought for many years now that these giant Chinese Dragons were actually embarrassing scared little field mice instead of roaring dragons sneaking timidly around town fearful of our Australian monopoly tigers managed by Kiwi CEOs.

LikeLike