Last week I wrote briefly about a short presentation, at a Victoria University event, by tax blogger (and former Treasury/IRD official, former adviser to the Tax Working Group) Andrea Black on what should be done with the company tax rate. Andrea argued that it should be raised, both to collect more tax from the “rich” and to reduce the evident opportunities for avoiding or deferring tax that differential rates for company, personal, and trust income creates.

Since what I wrote about that was buried in the middle of a long post, I reproduce the relevant section here

I wasn’t really persuaded. With dividend imputation, the company tax rate in New Zealand bears much more heavily on foreign investors (none of whom needs to be here) than it does on domestic shareholders. In a country with low rates of business investment and now relatively low rates of foreign investment, it seems cavalier to be calling for increases in company tax rates which the global trend is clearly downwards (at 33 per cent the company tax rate would be the second highest in the OECD). In defence of her position, Andrea invoked some old IRD analysis that company tax cuts haven’t made much difference to investment – IRD has a strong institutional bias towards a simple tax system and little real focus on productivity, economic performance or anything of the sort – while noting that “if you did care about foreign investors” – there were various technical tweaks (I didn’t catch them, but perhaps thin capital rules?) that could be adjusted to compensate them at least in part.

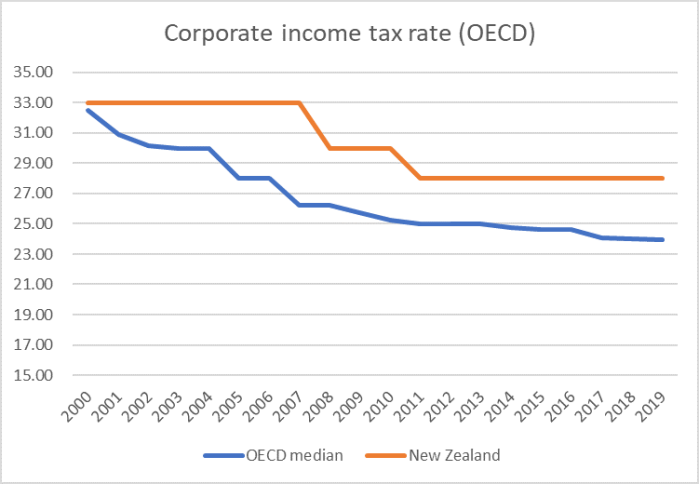

As if to forestall a question, Andrea alluded to this chart I’ve used several times – a version of which appeared in the TWG’s own background document last year.

Prima facie, it didn’t look as though – by international standards – we were undertaxing business income.

Now, of course, there are some well-recognised caveats to this data. First, it doesn’t take account of dividend imputation in New Zealand (and Australia, but not elsewhere), and the TWG suggested there were some issues around consistency of treatment of government-owned businesses. On the other hand, in many countries lots of shares are owned by long-term savings vehicles with much less onerous tax provisions than their peers in New Zealand would have, and our tax system (mercifully) has fewer deductions and “holes” in it. In yesterday’s presentation Andrea suggested that in many other countries various classes of business income that would be incorporated – and thus captured in the chart – here wouldn’t be treated the same way in other countries.

All that said, if anyone is seriously suggesting that the chart of OECD data is substantially misleading about the New Zealand position – say that in truth we might be in the lower half of the chart on an apples-for-apples comparison, the onus is probably on them to demonstrate that more specifically. The OECD data itself suggests we have taxed businesses quite heavily going back 50 years, to (for example) well before imputation was ever on the scene (chart in this post). Perhaps it is just coincidence – and I’m certainly not suggesting it is the only factor – that business investment as a share of GDP has been low by OECD standards throughout almost all that period.

In a comment on my post, Andrea clarified that it was changes to the thin-capitalisation rules she had in mind to mitigate adverse effects on foreign investors.

I’m sympathetic to the idea that New Zealand shareholders shouldn’t be able to shelter income in companies in a way that means that some forms of flow capital income are taxed more lightly than others. For small closely-held companies, for example, I can see a certain logic to a mandatory distribution of profits (which could then be simultaneously reinvested).

When I heard Andrea’s brief presentation last week, I hadn’t seen her initial post on the issue. It is worth reading and she presents what looks like persuasive indications that there is more of an issue here than (for example) some people who commented on my post or got in touch privately might have suggested. For example

Except that overdrawn current account balances – loans from the company to the shareholders- have been similarly growing too. Now sitting at about $25 billion.

And yes this all started from about 2010. And what happened in 2010? Why dear readers the company tax rate was cut to 28% while the trust rate remained at 33%.

Last night Andrea put out a further post on the issue, prompted (it appeared) by my post last week. It is also worth reading, repeating some of the earlier material but also extending her argument. For example, in dealing with the foreign investment issues she now suggests another possible response

If the focus was New Zealanders owning closely held New Zealand businesses, an adjustment could be made either by increasing the thin capitalisation debt percentage or making a portion – most likely 5/33 – of the imputation credit refundable on distribution.

I’ll leave you to read Andrea’s case. On its own terms, it makes a fair amount of sense on her terms (and she is much more expert on tax detail than I am) but I want to focus on the issue through a different lens.

Thus, take for example the line – which apparently originates with IRD – that we’ve had no more foreign investment since the company tax rate was cut. Well, here is a chart of New Zealand company tax rate relative to the median OECD country’s company tax rate (OECD data that take account of sub-national taxes as well).

The story of the century, around company tax, is that the gap has been widening between our company tax and those in other advanced countries (with the two local cuts just temporarily closing the gap a bit). At the start of the century, our company tax rate was around the median for the OECD countries, and in 2019 it is just over 4 percentage points higher. (One could add that the global environment for business investment seems to have been pretty poor over the last decade, not least in New Zealand.)

At present, our company tax rate – the one that counts for foreign investors – is just above the upper quartile.

Andrea’s proposal would give us the highest company tax rate in the OECD. One could adopt the clever wheezes she suggests to limit any adverse effect on foreign investors of raising the rate but (a) our statutory rate is already (now) at the upper end of the scale, and (b) our company tax regime is generally regarded as fewer holes and deduction possibilities etc than many of those in other countries.

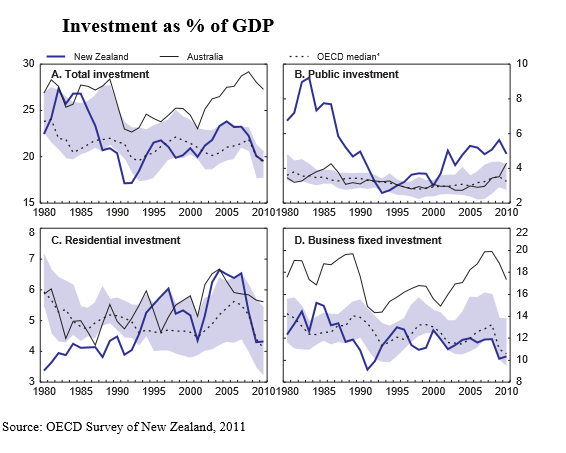

And it isn’t as if business investment has been present in abundance in New Zealand. This chart is from an OECD review of New Zealand from a few years ago.

Focus on that bottom right panel. The only time business investment as a share of GDP was above that for the median OECD country for a few years was during Think Big – the spectacular government-led misallocation of capital. And recall that for at least the last 25 years, our population growth has been well above that of the median OECD country, so that all else equal one might have expected more of current GDP to be devoted to investment.

I’ve seen – but can’t now find – the OECD data for these graphs back to the 1960s and the picture is similar, What about the more recent period?

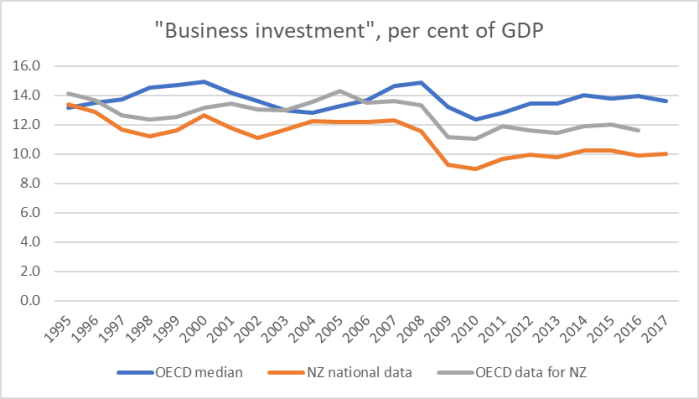

“Business investment” is calculated as a residual. Take gross fixed capital formation and subtract investment spending on new housing and general government investment spending. When I use OECD data for cross-country tables, I usually take care to check their New Zealand data against what is on the SNZ website. In this case, GDP, GFCF, and dwellings investment are all identical in the two places, but the general government investment numbers are somewhat different. So in this chart, comparing business investment as a share of GDP for New Zealand with that for the median OECD country, I’ve shown the New Zealand numbers estimated both ways (ie using OECD and SNZ gen govt investment data).

Whichever line you use, business investment in New Zealand (per cent of GDP) has been materially below that of the median OECD country in most/all years, despite having had population/employment growth far faster than that of the median OECD country.

I am not, repeat not, suggesting that our company tax rate – or the broader tax regime for capital income – is the only factor, or even necesssarily the most important factor, in our weak business investment (and terrible productivity growth) record. Simply that if any government were ever seriously concerned about those failures – and wouldn’t that be a novelty – raising the company tax rate looks as though it would be a step in the wrong direction. If anything, in my view we should be taxing capital income less heavily. No business has to invest – and no foreign investor has to invest here – and if you want more of something it isn’t usually a good place to start to tax it more heavily.

And to end on a note that seems to me to – at least on paper – better balance fairness and efficiency/opportunity, here is my final paragraph about that seminar last week at which Andrea spoke.

I remain tantalised by the idea of a progressive consumption tax. In the abstract, it gets around all the debates on capital gains taxes, realisations (or not), company taxes, gift or inheritance taxes or whatever, and has the appealing the feature of taxing people on what they consume not on what they produce. Of course, no country runs such a system – which does have formidable practical issues. And if one wants to align company and personal rates – which has some appeal (although the Nordic model questions that), better to lower the personal income tax rates by 5 percentage points (max rate to 28 per cent) and add a Social Security Tax of 5 percentage points on labour income up to a certain threshold. New Zealand and Australia are, as I understand it, the only OECD countries not to adopt some such model (we do it on a very small scale with ACC).

Perhaps a really,really simple tax on those outstanding Shareholder Loans would help.

4% on $25b would rake in a billion dollars a year.

LikeLike

Michael, as I have explained before, you need to exclude Look Through Companies(LTC). Your entire paper and its drawn conclusions are just wrong. LTCs are considered non-qualifying as they operate as partnerships for tax purposes.

The qualifying and non qualifying companies regime is more to do with the LAQC regime which is a Loss Attributing Qualifying company. The LAQC regime ended in 2010 with a 2 year transition to the LTC regime. LTCs operate as partnerships even though they are still closely held companies. No new elections can be made to become a qualifying company. Only companies that were qualifying companies before their income year started on or after 1 April 2011 can still be qualifying companies.

The falling trend for qualifying companies is due to LAQC transitioning to LTCs. Those qualifying companies that do not transition to LTCs will just continue as Qualifying companies after dropping the Loss Attributing aspect after 2010.

The qualifying and non qualifying companies regime is more to do with the LAQC regime which is a Loss Attributing Qualifying company. The LAQC regime ended in 2010 with a 2 year transition to the LTC regime. LTC’s operate as partnerships even though they are still closely held companies.

LikeLike

It is quite a laughable joke when Tax experts like Andrea Black and now Terry Baucher get it so wrong and perpetuate this innacuracy and do not offer any apologies or even attempt to correct their wrong conclusions. Even you Michael have not corrected your error.

As I have said before qualifying companies is the last remnants of the old LAQC. They still exist but it is impossible to create new qualifying companies as they are former LAQC companies that do not elect to be LTC companies. Non qualifying companies include LTC’s but function a partnerships for tax purposes. This error getting perpetuated by Andrea Black, then the Tax Working group, by you and noiw by Terry Baucher another tax expert is getting quite irritating.

https://www.interest.co.nz/business/103661/terry-baucher-reports-inland-revenue-gets-curious-about-advances-shareholders

LikeLike

For alternatives to increase investment and productivity, how about some of the relevant ideas from the very interesting paper “Reviving economic thinking on the right”. https://revivingeconomicthinking.com e.g. full expensing of investment, and replacing business taxes with taxes on commercial land value, payable by the landowner, together with an explicit land value tax to replace capital value rates. (For the arguments see the paper).

LikeLike

It’s amusing (and a little frightening) that tax “experts” like Andrea seem to think that the path to success is to punish – via higher taxes – our most successful citizens.

It would seem that her motivation is all about “equity” which strikes me as a pernicious form of socialism.

LikeLike

Probably a bit unfair. IRD has historically been sceptical that tax rates make much difference to business investment,.

LikeLike

Does this all come from the Left’s usual vision of “Companies” being owned and run by greedy men wearing top hats? Huge numbers of companies are small and medium size businesses owned by families, employing people and producing real products and services. The tax rate is already on the high side and if anything the company tax rate should be reduced to around 25% in keeping with international trends.

LikeLike

Also probably a bit unfair. The difficulty – a real one at present – is that the tax system is supposed to tax income in the hands of shareholders at their max marginal tax rate, typically 33%, but the lower company tax rate (after 20 years when they were aligned) now encourages people to avoid distributing where possible. Given the IRD vision, there is a logic to Andrea’s position: my problem is more with the vision that has guided tax policy in NZ since 1988.

LikeLike

Given New Zealand doesn’t invest ‘enough’ in capital (i.e. the capital component of multi-factor productivity) wouldn’t it be worthwhile also considering how the treatment of depreciation could encourage companies to use the latest capital equipment as much as is practicable?

This in combination with a lower overall rate would surely help with the productivity conundrum?

LikeLike

At the extreme you get to the immediate full expensing of capital, as proposed in that interesting paper that William Foster linked to earlier. Again, one has to think about the appropriate conception as to how to treat business income, and immediate full expensing or accelerated depreciation don’t fit with the post-88 tax policy vision (in 2010 we even took things in reverse and eliminated depreciation on buildings – a populist and incoherent move that meant that, on Tsy’s numbers at the time, altho the headline company tax rate was lowered the effective average company tax rate went UP.

LikeLike

You are correct that no other country has a comprehensive progressive consumption tax, Michael, but plenty of other countries have made movements in that direction by adopting an “Exempt-Exempt-Taxed” (EET) approach to the taxation of savings made through specifc retirement saving accounts. The intellectual case that an EET retirement income tax system is a progressive consumption tax was made by Irving Fisher back in 1937, and reinforced by Lord Kaldor in his 1955 book “An Expenditure Tax” – and then reaffirmed by various high level British investigations into the tax system such as the Meade Report and the Mirrlees Report. What is strange is how NZ policy makers seem determined to ignore the case for progressive consumption taxes since they got rid of them in 1989. It is also strange that NZ tax experts seem determined to ignore standard tax theory and international practice that there is no need to tax capital income at the same rate as labour income, and , if capital investment flows are more sensitive to tax rates than labour supply (as international evidence suggests, and as those right wing Scandinavian countries believe) then capital income should be taxed at lower rates than labour income rates.

What would be interesting is to hire a sociologist to study why NZ tax experts are so sure standard tax theory doesn’t apply in New Zealand, so that it is important we have amongst the lowest taxes on labour income in the OECD and the highest taxes on capital income. If we understood where these beliefs came from, we might have a chance of understanding whether they were based on evidence or just reflect group-think.

Andrew

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Andrew. I was hoping you would comment along those lines.

LikeLike

Sorry if this is a double up, as had trouble posting../

A lot of nonsense in comments and from Black regarding over due shareholder current accounts: for non shareholder ‘employees’ the value of interest if not charged by company is taxable as a dividend; for shareholder employees (allocated salaries for personal services) FBT is payable at very unattractive rates on value of interest not charged; so the company normally will have to charge interest on the overdrawn balances at (high) FBT rates: taxable to company and not deductible to shareholders. Far more likely these o/drawn accounts are a sign of initially distressed companies out of GFC 2009, and now zombie companies, particularly dairy farms, created by RBNZ stimulunatic low interest rates.

LikeLike

Yes. The assumption drawn from the Black article is that all the companies with loans to shareholders are operational. Possibility is a good number are dormant and non-operational and not contributing to GDP

LikeLike

Most of these shareholders loans operate through Look Through Companies(LTC) which already have forced profits distribution and pays the full individual tax rate of 33%. These entities can’t pay out dividends as they operate as partnerships for tax purposes even though they are closely held companies.

Under current tax legislation IRD already has the discretion to deem a dividend on Shareholders loans if they believe these are actually personal drawings from ordinary companies.

LikeLike

Further to my comment above:

I said they will be distressed firms because these will almost all be the over drawn accounts of shareholder employees for whom the companies have not made enough profit to allocate salaries big enough to cover drawings taken over the year. These will be companies in trouble (and those over drawn current accounts are a nightmare on liquidation so you do not let them build up by choice).

Further, they will not be non shareholder employees as unimputed non-cash dividends would be a ludicrous policy for a company to run.

Again, the ignorance of Black here is, well, educational.

LikeLike

Andrea may choose to comment (and I don’t have a particular view on this issue) but as I understand it several of her charts were taken from TWG material, where Tsy and IRD will have been involved. Do you have a good story for why the changes shown in the charts seemed to show up only from around 10 years ago?

LikeLike

On holiday in Brisbane at the moment so was only referring to her inferences from overdrawn shareholder current accounts. As stated, my belief is these will be distressed companies out of GFC that can’t cover shareholder employee drawings with salaries (profit), and more recently many of these firms created as businesses are being zombified by RBNZ low rates (many dairy farms now, the big highly indebted ones that would not have been converted if we’d had market rates not stimulunatic rates, are being actively managed by their banks because they are long term unprofitable even on a milk payout above historical averages).

They won’t be companies trying to avoid tax (company retained earnings are only a tax deferral, anyway, not a permanent tax dodge, as they have to be distributed to shareholders some stage) far more likely they are unprofitable companies not paying, or barely paying tax via what salaries they can distribute).

Note I agree with Black that the disparity between corporate rates and top personal and trustee rates is really bad policy (although the fix it to reduce trustee and personal rates down to 28% (if the desire is for free lives and prosperity).

LikeLike

Although 🙂 if Andrea Black is reading these, the TWG was a huge disappointment against Western classical liberal values – as I’ve told Geof (her fellow TWG member who is a good bloke that I know loosely via Twitter).

The whole work of that group was toward taxing capital (taxing everything), and so a huge opportunity for justice and fairness was missed. My savings are pretty much all term deposits and fixed interest (done well in bond rally, giving much of that back in bond rout up to yesterday). I won’t touch these bubble sharemarkets made by the central banks because to get back to reality they have to collapse harder than the GFC 50% (S&P). But that means I, like the elderly, have been watching deposit rates be destroyed to the point that after tax (and I use PIEs to limit that to 28%) I’ll be making negative real returns on all my next rollovers from October: if the TWG had gone the way of a free society and prosperity by recommending the abolishment of taxes on savings, starting with abolishing RWT, then at least the elderly, many of whom paid 18% and more on their mortgages, would have a little chance of at least keeping up with inflation with their retirement savings. And it would have incentivised saving. But the TWG, along with RBNZ chose to sacrifice the elderly on the Everest mountain of debt command economy policy has created; and the lowest returning savings, interest income, continues to be the most viciously taxed, which I find extraordinary. Indeed RBNZ policy is now specifically anti-savings, the power house of all free economies: totally absurd and reckless. While many elderly in desperation have sadly taken on inappropriate and huge risk just to try and eek out a little more joy, which will end disastrously for them (I believe globally central bank policy has been not only reckless, but immoral and negligent).,

You’ll be pleased to know I’m out for breakfast now 🙂 Sorry above doesn’t read the best, but I’m on a poxy wee hotel table and a tiny keyboard.

LikeLiked by 1 person