Today is, apparently, the 30th anniversary of the Public Finance Act. There is a conference being held this weekend at Victoria University to mark the occasion, with all manner of speakers over three days, including various famous figures from the reform era including Roger Douglas, Ruth Richardson, Graham Scott, and David Caygill.

There is nothing particularly wrong with conferences of this sort – although the ever-present question is how much taxpayers’ money gets spent, one way or another – but much depends on the extent to which such conferences lean towards on the one hand the self-congratulatory and, on the other, the self-scrutinising and challenging. There was a conference in Wellington a few years ago to mark the 25th anniversary of inflation targeting and the Reserve Bank Act, and although it leaned to the mutually self-congratulatory, a) it had speakers who seemed to offer greater rigour than this weekend’s conference programme suggests is likely, and (b) even partial sceptics occasionally got a word in. Time will tell about this weekend’s conference, and I hope that at least the New Zealand academic and public sector speakers make their addresses available more widely.

I have no particular problem with the Public Finance Act, which now incorporates the provisions of the later Fiscal Responsibility Act. But what consistently irks me is the way a handful of champions of the Act oversell it. Most prominent among the oversellers in Professor Ian Ball of Victoria, who had a fairly senior role in financial management at The Treasury at the time the Public Finance Act and the Fiscal Responsibility Act were being passed. And the real prompt for this post was an article he had in yesterday’s Dominion-Post. Whatever else Professor Ball picked up, or contributed, in his time at The Treasury, he seems to have missed the pretty elementary line, drummed into students from an early age, that correlation is not the same as causation. And that isn’t the worst of what was on display in the article.

He begins

When New Zealand’s Public Finance Act was passed in 1989, it represented a set of changes that was both radical and untested. Partway through its implementation, in 1992, the Economist published an article describing the changes in a generally positive way, but withholding judgment and concluding: “Time will tell.”

With the act’s 30th anniversary on July 26, it seems the right moment to consider what time has to say, and whether New Zealanders should, at last, break open the bubbly.

To jump to the end, he thinks we should be breaking out the bubbly. But why?

Much of his case seems to rest on this

[Government] Net worth now stands at over $134b, equivalent to about 45 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP).

But he makes no effort at all – not even hinting at more-developed arguments in fuller papers – to demonstrate why we should conclude that the improvement in New Zealand’s fiscal position stems in whole, or even in large part, from these process-focused pieces of legislation (Public Finance Act and Fiscal Responsibility Act). He also offers no particular reason to suppose the government net worth of 45 per cent of GDP is somehow optimal, or better than (for example) a number near zero, or even negative (given that by far the Crown’s largest asset, its sovereign power to increase taxes is not included in these balance sheet calculations, and that the actual taxes supporting the net worth Professor Ball celebrates have material – large in some cases – deadweight costs, in an economy that has continued to badly underperform).

And while no one is going to disagree that a decent fiscal position (whatever that means) can be a “source of security” (Ball’s words), the evidence he adduces in support of his claim is less than convincing.

The comparison with other countries is striking – the governments of Australia, Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom all have significantly negative net worth, and in the case of the UK and US the negative net worth is roughly the size of their respective GDPs.

The principles of fiscal responsibility imported into the Public Finance Act from the Fiscal Responsibility Act see positive net worth as a “buffer” to economic and other shocks. So it has turned out.

While net worth declined for only four years after the financial crisis, in the four countries cited above government net worth remains, a decade later, on a downward track. A strong balance sheet apparently allows a much quicker recovery.

But, but, but…..Our recovery wasn’t “much quicker”, let along stronger, than those in Australia (which on some measures didn’t have a recession in the first place), Canada, or the US. And whether one approves of those choices or not, the fact remains that unlike those countries we didn’t use discretionary stimulatory fiscal policy to respond to the last recession (I argue we didn’t need to because we could still cut interest rates).

Ball continues with his straw men

But has the history of running surpluses resulted in slower economic growth than in the comparable countries that have been incurring consistent deficits?

I’m not sure anyone would think there was such a relationship, but set that to one side. What does Ball have to say?

Apparently not. The latest World Bank numbers (for 2017) show that the five countries have growth rates between 1.8 and 3.0 per cent, with New Zealand second at 2.8 per cent.

Can he be serious? A senior professor, former senior official, really thinks one year’s GDP growth data, not even correcting for differences in population growth (hint: New Zealand’s has recently been extremely rapid) is some sort of support for his case about legislation focused on the medium to long term?

Perhaps instead he might consider the productivity record over 30 years? Of his group of countries, ours has been the worst (to be clear, I’m not suggesting that has anything to do with the PFA, simply that one can’t seriously advance New Zealand “economic success” as support for the PFA).

He moves on to matters social.

Perhaps, then, the impressive fiscal and economic results have been at the expense of the social fabric? By no means are things perfect in New Zealand.

To which he responds

The Wellbeing Budget in May focuses on problems of child poverty and mental health, among many other issues that require government attention and resources. Yet these issues are still able to be addressed while budgeting to maintain a surplus.

Few of the (few) cheerleaders for this year’s Budget would claim it was any more than a start, but since the PFA was never supposed to constrain the size of government (it is mostly about process and transparency), of course it doesn’t stop governments spending more – wisely and otherwise – if they choose.

Ah, but we are “happy”

New Zealand stacks up very well, scoring near the top in a number of international rankings of social progress, living standards and even happiness (where we are eighth, ahead of the other four countries).

And yet – and not because of the PFA – the net flow of New Zealanders is still from here to other countries.

We then get into the folksy analogies

But do New Zealanders benefit from their government having a strong balance sheet?

It is very like having a strong personal balance sheet. There is a greater ability to absorb shocks or surprises without being forced into taking drastic remedial steps – you can fix the car without having to cut the food budget. This was demonstrated in the way the government bounced back, financially, from the financial crisis and the earthquakes.

As part of managing a shock, a strong balance sheet also enables easier access to emergency debt financing. Coupled with this is the benefit of being able to borrow more easily and more cheaply in normal times, if it is necessary or desirable to do so. This might be useful, for example, if there is a need to invest in infrastructure.

I like a folksy analogy as much as the next person, but you always need to be careful using them to ensure that the key elements of comparison are valid. Here they mostly aren’t. Positive accounting net worth means nothing about a sovereign’s access to credit, none of the comparator countries whose fiscal performance he laments have had any problem raising debt, New Zealand bond yields (for other reasons) have been consistently among the highest in the advanced world……and, unlike someone whose car breaks down, governments have the power to tax. And did I note that there was nothing impressive about New Zealand’s recovery from the 2008/09 recession, and New Zealand’s productivity record this decade is even more dire than usual.

And then, without even really noticing, he rather undercuts his own case.

At the time the Public Finance Bill was going through Parliament, the auditor-general said the reforms “will give effect to the most fundamental changes to financial management practices seen in New Zealand’s history. These reforms are enormous, ambitious, and, in large part, unprecedented anywhere in the world”.

Thirty years on, the act has been amended several times, but the most ambitious elements remain firmly in place. Notwithstanding the apparent success of these reforms, a number of key elements have been attempted by few, if any, other countries.

Reforms that, 30 years on, have not been followed by many, if any, other countries surely should be deemed to have failed an important test. Other smart people have looked at those “key elements” and concluded that actually they weren’t so valuable or generally appropriate after all. It was a bit like that with the Reserve Bank Act and inflation targeting: various countries did take some practices and inspiration from our model, but not a single one followed for long our model of putting all the power in the hands of a single Governor and building an accountability framework primarily around the ability to sack the Governor. Eventually, even New Zealand changed those bits of law, and moved back towards the international mainstream.

Professor Ball ends this way

In October 2018, the Economist weighed in again, saying: “Only in one country, New Zealand, is public-sector accounting up to scratch. It updates its public-sector balance-sheet every month, allowing for a timely assessment of public-sector net worth.”

Perhaps, ahead of any further changes, this might be an opportunity to raise a glass to celebrate an ambitious and successful act.

I don’t update my personal balance sheet every month. Superannuation funds I’m a trustee of don’t look at their balance sheets every month. For what conceivable practical purpose do we have monthly estimates of the government’s financial net worth? At best, financial net worth is some sort of constraint on governments, not the reason for being – as in, say, corporate accounts. I’m not necessarily opposed to having the data, but it looks a lot like an example of giving prominent place to what is measurable (on all sorts of assumptions) and not necessarily to what actually matters. We don’t even need monthly house price data (although we have it) or monthly productivity data (we don’t, and probably shouldn’t) to highlight these egregious failures of New Zealand governments. And monthly government net worth data – or the rest of the panoply of features of the PFA – has done nothing discernible to improve the actual quality of New Zealand government spending (or taxation).

As I’ve argued repeatedly here over the years, I think fiscal policy outcomes are something that successive waves of New Zealand politicians can take considerable credit for. We had a bad scare in the mid 80s and early 90s and that clearly played a pretty formative part, both in choices political parties made in successive elections/budgets, and in the legislation (eg PFA/FRA) they’ve been willing to pass – but my hypothesis is that there is a common explanation for both, rather than causation running from the (facilitative, transparent) legislation to the fiscal outcomes.

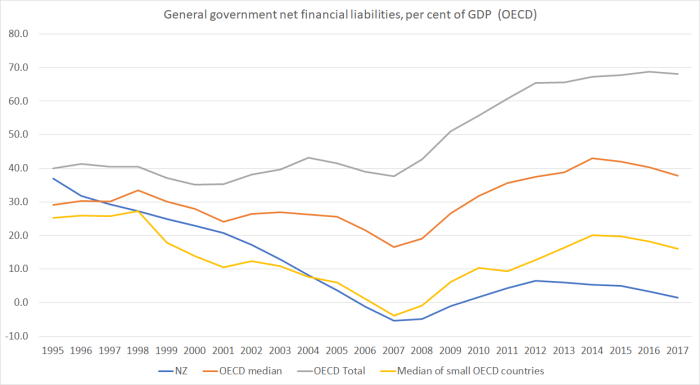

I tend to be relatively sceptical of net worth numbers (for governments) and the data often aren’t available for lots of countries for long runs of time. But I’ve run this chart in an earlier post, looking at net general government (ie all layers of government) financial liabilities.

Here I’d concentrate on the comparison between the blue line (New Zealand) and the yellow line (the median of small OECD countries). New Zealand’s performance doesn’t particularly stand out relative to those other small countries (or to Australia, which has lower net general government financial liabilities than New Zealand), even though we – like them – even though there is a stark contrast to several of the largest OECD countries (notably US and Japan).

Any story about the successes of New Zealand fiscal policy that tries to put much weight on New Zealand specific legislative reforms needs to grapple more seriously with the experience of other well-governed small advanced countries, and make more effort to demonstrate how our legislation accounts for any (rather more marginal) differences. It also has to ask how credible is a story that suggests that, say, US fiscal problems result largely from, say, insufficient transparency (and other bureaucratic type solutions). In that respect, it is a bit like the Reserve Bank Act: it wasn’t responsible for the much lower inflation of the 1990s and 2000s (there were global phenomena at work, including widespread political choices to lower inflation), but was a broadly useful framework for managing a commitment to lower inflation and (at least in principle) being open and transparent about how policy would be conducted.

I guess it is good to be able to be proud of things one was involved in over the course of one’s working life. But I hope this weekend’s conference is a bit more rigorous, and self-scrutinising, than what was on display to Dominion-Post readers yesterday. Careful evaluation, careful analysis, should be key inputs to the design and updating of good policy.

Yes the mighty Professor doesn’t seem to understand basic accounting either Michael. For the government to have accumulated significant net worth, it doesn’t occur in a vacuum. By definition, it means that this wealth has been transferred from the private sector; business and households.

Yet more evidence that our tax structures are misaligned. And on that topic, if they’d really done a good job they’d have indexed tax brackets to prevent bracket slippage…

LikeLike

Land and building revaluations do occur in a vacuum. I bought 2 houses on a cross lease on 1 title in Mt Roskill 15 years ago for $600k. When the Unitary plan was released in 2017 the value of the 2 houses was $1.4 million. I just completed a subdivision with the final titles issued a month ago. The Auckland Council just issued a ratings valuation on the 3 new titles now at $2.5 million. I paid $25k for the 2nd hand 4 bedroom, 130sqm house and relocated the house as is. I then paid $600k for relocation, earthworks and services.

LikeLike

I can recommend this interview with Joe Gagnon. http://macromusings.libsyn.com/joe-gagnon-on-currency-manipulation-trade-imbalances-and-libra. In short, fiscal discipline is a major contributory factor in maintaining a favourable BOP/exchange rate equilibirum (which I think would go a long way to solving our productivity disaster).

So I am old-school (and increasingly out of touch, it seems) in thinking we should actually pat ourselves on the back for fiscal discipline. However, we totally undercut ourselves with our anti-savings tax and welfare system, so ending up with the high interest rates that you mention.

LikeLike

NZ Households have $181 billion in savings deposits, $103 billion in Investment fund shares and $105 billion in Insurance and Super funds. That is a total of $389 billion in savings for 4.6 million people. Is that actually that bad?

LikeLike

Ha! A positive net worth boosted by current land valuations – top job….

LikeLike

interesting to see how large a contribution such land values make. I don’t have a good sense of how much urban land central govt has. I guess schools and state houses will be the two big ones.

LikeLike

land is valued at $52 billion. this includes the conservation estate which is valued at 6 billion. I would put a figure more like $106 billion on it. if my advice is followed then the reforms would have been even more successful.

it is comforting to know that if we get into financial trouble, we can sell off the conservation estate, though i fear that the idiots who produce the report will be happy to let it go at book value.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That figure of $52 billion looks rather light in the context of NZ Household land values that amount to $838 billion.

LikeLike

The world he grew up in took a turn for the worse around 30 years ago, he says. If you wanted a date, 1984 would be a good place to start. “I guess when you look back at the big picture, back in those times we were just [entering] Rogernomics.”

Prior to Roger Douglas’s introduction of neoliberal economic policies, he says, there was affordable housing and plenty of jobs in Gisborne. “You had the Gisborne freezing works, you had the Wattie’s company here. That provided income for a lot of whanau.”

When the jobs disappeared, the issues began and built over time, he says. “When you look back on the statistics, you start seeing over the last 20 years that there’s been a gradual climb with a lot of statistics around abuse. It all stems from poverty really.

http://shorthand.radionz.co.nz/maori-poverty/index.html

and the Labour government decided we needed a bigger population but that is accepted as a good thing @ RNZ

LikeLike