That was the title of Wellington economist Peter Fraser’s talk at Victoria University last Friday lunchtime on why Fonterra has failed (it is apparently also a term in use in various bits of popular culture, all of which had passed me by until a few moments ago – and a Google search). Peter is a former public servant – we did some work together, the last time Fonterra risks were in focus, a decade ago – who now operates as a consultant to various participants in the dairy industry (not Fonterra). He has a great stock of one-liners, and listening to him reminds me of listening to Gareth Morgan when, whatever value one got from purchasing his firm’s economic forecasts, the bonus was the entertainment value of his presentation. The style perhaps won’t appeal to everyone, but the substance of his talk poses some very serious questions and challenges.

The bulk of Peter’s diagnosis has already appeared in the mainstream media, in a substantial Herald op-ed a few weeks ago and then in a Stuff article yesterday. And Peter was kind enough to send me a copy of his presentation, with permission to quote from it.

His starting point is with the misplaced belief among senior political figures 20 years ago that by allowing the creation of Fonterra – using legislation to override the Commerce Commission – the door would be opened to the evolution – in pretty short order – of something equivalent to New Zealand’s Nokia. In revenue terms, the promise had been

From a starting point of only $5B, they outlined a six-fold increase in revenues in only 10 years to $30B.

Critically, just under two-thirds of the $30B would come from what is euphemistically known as ‘value add’: specialised ingredients and biotech-heavy products.

So this was almost $20B of revenue from a starting point of ‘nothing’.

Actual revenue now, 17/18 years on, is about $20 billion (including a structural improvement in world dairy prices) and relatively little is from those vaunted specialised products. The rate of return on that business, in turn, is barely higher than that on the bulk commodity business.

And

A much cited figure is the 2018 value report published by the International Farm Comparison Network (IFCN). This ranked Fonterra 17th out of the 20 companies in terms of value creation.

Its figures show while Fonterra collects the second largest amount of milk (and is the world’s largest milk exporter), its estimated turnover per kg of milk solids is only US60c.

By comparison, Danone is the 11th largest milk processor, but it turns over US$2.40 for every kg to make it the best performer. Nestlé is next at US$1.90 per kg. The average across the entire group is $1.00.

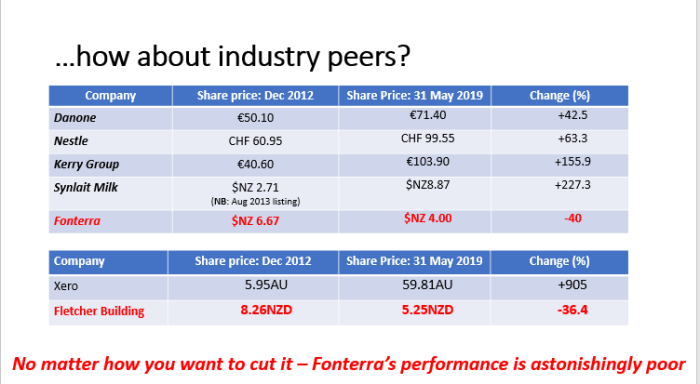

The “failure” is nicely illustrated in the share price (the non-voting shares were listed in 2012). The comparison against the NZX index is stark, as is that against industry peers.

Apparently the share price fell further in June (and Peter told us that on Thursday the share price closed a touch below the initial valuation back in 2002).

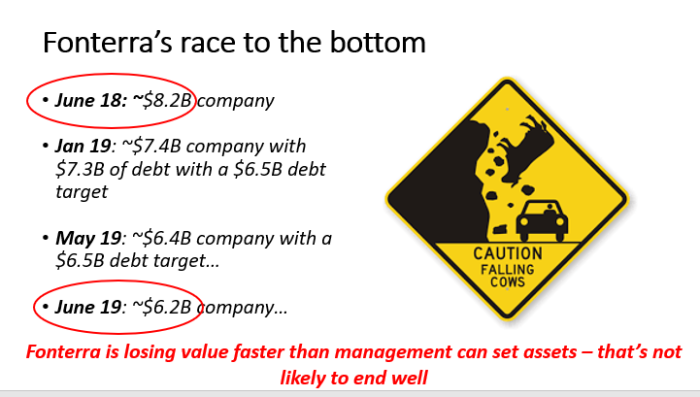

Fonterra asset sales have been in focus this year. They started when the market value of the company was much higher than it now is, and haven’t kept up, so that the ratio of market value to debt is now higher than it was.

For various reasons I don’t want to get into the fine details of DIRA, but as I understand the essence of Peter’s story is that:

- farmers themselves never much cared about the added-value ideas (New Zealand’s Nokia and other dreams). Why would they? They are farmers, and their interests were primarily about a high price for their milk, and a high/rising price for their land.

- between provisions in the legislation and in the constitution of Fonterra, the rules mean Fonterra has been paying materially too much (Peter says 50c per kg) for milk purchased from suppliers,

- dividends on the shares have been limited, which doesn’t matter to (voting) farmer shareholders, but does matter to the outside shareholders, and retentions (or retaining earnings) – now the main source of additional capital in a cooperative – have also been low.

- given Fonterra’s dominant market position, the too-high milk price also drives up the price of milk other industry participants have to pay. That has encouraged more milk production – including “half way up Mt Cook”, and with associated environmental issues – but also makes it difficult for firms to make profitable investments in other (value-added) products.

Peter again

…the idea of using the ingredients business as a springboard to a value creation business was part of the original concept and is actually a good one.

The problem is, it basically didn’t happen. There are two reasons for this.

Firstly, Fonterra relies heavily on payout subordination so has very high gearing – something it seems the Board has failed to learn from after courting near disaster during the GFC.

This constrains Fonterra’s ability to borrow further, such as for acquisitions or to finance value creation activities.

The other problem is woeful levels of retentions, which are critical for a coop because without new capital from a growing milk supply, retentions are only other way of getting new capital.

So Fonterra remained a capital starved, deeply indebted and under performing farmer-owned cooperative.

That “near-disaster” ten years ago (his account here) was when I first met Peter. Global funding markets was seizing up, world dairy prices had fallen sharply, land prices were falling, and lenders to dairy farmers were becoming seriously uneasy (including parents in Australia that hadn’t fully appreciated quite how much exposure, to a sector with very illiquid collateral, had been taken on). In those days, struggling farmers had one buffer and Fonterra one exposure, that doesn’t exist today – redemption risk (on the farmers’ own production-related shares in the co-op).

That particular risk has now been shifted back onto farmers, which probably leaves Fonterra’s own lenders a bit more comfortable (but in turn removed one discipline from the Board). But there is still a hugely high level of debt (presumably largely from international markets and banks).

Peter argues that, unless something dramatic changes pretty soon, Fonterra is likely to run into crisis within the next five years or so (and, he argues, since the current government probably likes to believe it will still be in office five years hence, they really need to focus on this now).

I was among those at the presentation the other day who weren’t entirely sure how this mooted crisis would come about, or what form it might take. After all, Fonterra isn’t a conventional company. The traded shares – the price of which has been falling away – are not a direct stake in Fonterra. The share price could go to zero (if, say, unit holders lost confidence there would ever be dividends, tied to value-added returns) without rendering the co-op itself insolvent. The banks and bond markets that have lent to Fonterra are exceedingly unlikely to lose their money – that is what (milk) payout subordination means – but it is likely that quite a few of the existing facilities have caveats and covenants about financial conditions Fonterra has to meet. And the asset sales programme of recent months seems fairly explicitly premised on the idea that the market price of the shares (and those the notional market value of the co-op) mattersa, including to lenders. Presumably there has to be a risk that if Fonterra’s underperformance continues, lenders would become increasingly reluctant to renew existing facilities, and the costs of what credit they could still obtain would rise?

And, of course, there is only so much money to go around (perhaps rather less if commodity prices were to fall away sharply in a recession in the next few years), and what is paid to providers of capital (debt or equity) can’t be paid to farmers. The dairy farm industry has an uncomfortably high, and rather concentrated, level of debt already. And dairy land values are underpinned, to a considerable extent, by the actual and expected milk price. 50 cents off the milk price for one year might not make much difference to land values, but if Fraser is right and prices are perhaps 50c too high generally, adjusting the milk price itself into line with that would severely impede the profitably of many dairy farms (as Fraser notes, on-farm costs have been rising, and much of any margin New Zealand dairy farmers had relative to the rest of the world appears to have been greatly eroded. Fonterra also risks losing suppliers, and ending up with stranded assets.

The sketch outline of Peter Fraser’s story – directional pressures – seems plausible to me, but here I’m mostly trying to tell his story rather than sign up to it all. I don’t claim enough industry familiarity for that, and haven’t been exposed to serious alternative arguments – if there are some, bearing in mind the repeated underperformance over a long time now. The Fonterra statement to Stuff, in response to Fraser, didn’t instill great confidence

Fonterra managing director co-operative affairs Mike Cronin responded in a statement:

“Our focus right now is on the future of our co-op. We’re well down the path of a strategy review which will enable us to deliver on our potential and meet people’s expectations. We know where we want to go, but how we get there will take time. We will play to our strengths – our New Zealand provenance, our pasture-based farming model and our dairy know-how.”

Fraser’s presentation ended with these lines

That final line – Westland as dress rehearsal – is also where I want to end. Fraser argues that, most likely, Fonterra will need extensive recapitalisation and that – short of nationalisation – there is no likelihood that the New Zealand market could provide the necessary capital, and thus that a foreign takeover is the most likely market solution.

Perhaps it would be the eventual market solution, but I struggle to believe that the market would be allowed to operate in such a case. The politics of foreign ownership of Fonterra would be too much for any major political party – in today’s climate – to swallow. Most likely, we’d have government moneypots – the New Zealand Superannuation Fund and ACC – corralled to provide the new capital (those two are already half owners of KiwiBank, and NZSF falls over itself to pursue politically-attuned projects).

If I read Peter correctly, he believes things could be turned around. But that there is little sign of it from either Fonterra – and no demand for it from their farmers – or from the government.

“a foreign takeover is the most likely market solution”

Xenophobia aside, why do we care?

LikeLike

I don’t see any sign Peter does. Within limits, I don’t either. As per my submission on the foreign investment review (second half of this post https://croakingcassandra.com/2019/05/23/the-prc-trade-foreign-investment-etc/ ) i would favour open slather for advanced country investment, don’t mind open slather for private sector investment from most of the rest of the world, but believe PRC foreign investment should be restricted, both because it is effectively state-controlled (SOEs don’t typically do well) and because of the national security/political system integrity risks especially associated with the PRC at present.

PS I am however 100% sure that foreign ownership of Fonterra will not be allowed to happen, because the very prospect (once it became serious) would induce some sort of existential crisis of the “what is left, what is become of us” sort. Given our longrunning relative economic failure, such a crisis might not be a bad thing – just a shame if the energy is all spilled over who should own Fonterra.

LikeLike

You are most probably right about 100% foreign ownership of Fonterra, but such a “crisis” is not an economic debate, its (xenophobic) politics pure and simple.

LikeLike

I also see an issue with government investment, but its an issue not just for foreign government investment but also NZ government investment. In short, governments shouldn’t be involved with such things. As stated the Fonterra set up works for farmers and as they own it isn’t them being happy the point? Also, there are good reasons why you see cooperatives in farming so I’m not sure such a structure is so bad.

LikeLike

Largely agree, and totally on govt investment. Re Fonterra, yes it works for its members- as really a tolling operation- but peter makes the point that specific legislative provisions are also skewing the rest of the industry away from the sort of investments they would be making if Fonterra was paying the milk price it can really afford to pay ( rather than the one the formula dictates). If there is a policy issue at present it is probably to look again at that issue.

LikeLike

Yes, I have wondered about bits of the legislative set up for Fonterra. Changes there could bring in more competition which is the real test for whether or not the current Fonterra organisational form is the right one.

LikeLike

“In short, governments shouldn’t be involved with such things.”

That’s a great story. Westland being bought by Yili, a Chinese state-backed enterprise, is essentially a government getting involved in these things – just not ours. Since “xenophobia” seems to be your word of the day, you may proceed. In this context I am proud to feel responsibly xenophobic, so don’t expect much traction.

LikeLike

I think Paul was largely agreeing with you: govt ownership of industry (whether NZ or PRC) is very far from desirable.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not sure about that. I don’t place Chinese or domestic government control anywhere near each other on the desirability continuum.

LikeLike

As Michael said, I think we do agree, no government should be involved in owning businesses.

LikeLike

The government does need to step up and identify future industries that it needs to provide incubation capital. The prime examples would be Air NZ or the BNZ and subsequently Kiwibank. Space does look to be the next high tech frontier that we should be heavily invested in but have allowed too early, easily and cheaply to have slipped into foreign ownership.

Heavily subsidising Tourism and Primary industries as we have been doing just does not future proof NZ in terms of keeping up with the latest high tech manufacturing and products.

LikeLike

Fonterra’s milk price has been set since its inception by a quite complicated but ultimately transparent system reflecting commodity prices and manufacturing costs. It is unfair to say that farmers set their own price.

Fonterra has a huge problem in having to accept all milk offered to it, so it runs to stand still on differentiation. That said, poor performance was to an extent locked in by choice of the first CEO in my personal opinion. Organisations which have job titles which cannot be understood by outsiders often run into problems, in my limited experience.

LikeLike

I think peter’s point is that Fonterra should be paying less to farmers (than the formula price) and that Fonterra farmers have had no incentive to push for such changes. As he says, Fonterra works ok for their farmers. It was never going to produce the Helen Clark aspiration, and may be skewing the overall dairy sector towards more milk production and less investment in value added products etc.

LikeLike

Two points.

The entire milk price manual process and the use of a Hypothetically efficient process was all Fonterra’s idea, as it ensured a future Fonterra couldn’t reduce the milk price – which is farmers eternal fear.

It was basically the quid pro quo for TAF.

Secondly, Fonterra wanted an increasing milk supply – it’s goal until recently was 3.5 percent annual compounding growth.

So DIRA making Fonterra an open coop is precisely zero excuse – especially given ‘fair value’ rather than nominal shares (c/f. Westland).

LikeLike

To express concern about foreign ownership and control in New Zealand is often to invite accusations of xenophobia and economic illiteracy. It is worthwhile, therefore, to rehearse the grounds for that concern, and to explore the various forms it can take.

The most obvious manifestation of foreign influence is when New Zealand assets pass into foreign hands. The downsides of that change of ownership are largely to do with the loss of economic benefit.

If a significant part of the New Zealand economy is bought by overseas interests, the economic benefits produced by that asset – the income stream, the capital appreciation, the technological know-how, and so on – flow offshore rather than remain in New Zealand.

The consequence of such developments and of the repatriation of profits to foreign owners across the exchanges is that we are a smaller and less wealthy economy than we would otherwise be, and have greater difficulty in balancing our overseas payments – which acts in turn as an inhibitor to future growth.

http://www.bryangould.com/how-much-foreign-control-s-acceptable/

LikeLike

Can you explain how you think profits can be repatriated? Say I have one NZ dollar of profits, how do I take this dollar overseas?

LikeLike

I don’t understand your point, Paul.

If, say, the Australian and New Zealand Banking Group, wanted to repatriate a dollar (more likely a million dollars) profit from New Zealand to Australia, it buys Australian currency selling the NZ dollar. Isn’t that taking profit out of the country? I’m not an economist. Perhaps you can explain how the profit stays in New Zealand.

What is the point of investing in a foreign country unless you are able to remit profit to your own country?

I think you’re wrong in your earlier post in branding any questioning of overseas investment as “xenophobic politics” rather than an economic question. Does China reject foreign purchases of land and most foreign investment in its core steel industry on xenophobic grounds? Of course not. It bases this on its commitment to Marxism, a commitment President Xi is renewing. Marxism is economics as well as politics and morality. Are Singapore’s restrictions on foreigners buying property xenophobic? I don’t think so – Singaporeans are tolerant people.

Foreign investment is mostly beneficial, but to brand any questioning of it as “xenophobic” is to weaken that word, just as the extravagant use of the word “racism” weakened that term.

LikeLike

Sell NZD and buy USD. If NZD selling exceeds NZD buying the currency value drops. We end up with hyperinflation.

LikeLike

“Sell NZD and buy USD. If NZD selling exceeds NZD buying the currency value drops. We end up with hyperinflation”

So if I’m selling someone has to be buying my NZ$1. Why are they buying, what can they do with a NZ$1?

And how did you get to hyperinflation?

LikeLike

No one wants to accept your NZ$1 because everyone is selling NZD. That is called hyperinflation.

LikeLike

Ask yourself if NZ$ are being sold what does the buyer do with them? There is only one thing he can do, buy something from NZ. The money returns.

LikeLike

I don’t want to weigh in at length, and in general I think I’m closer to Paul’s view (although I find “xenophobia” as unhelpful a term as any of the “…phobias”, outside a clinical context). But while I agree that every seller of NZD has to find a buyer (that is what a floating exchange rate means) – and so to say “money” flows out of NZ isn’t correct – there is no guarantee that occurs at an unchanged price. A lower exchange rate is a loss of NZers’ purchasing power.

More generally, of course, one needs to think about the issue in a gen equil context: even if ownership of one firm changes hands, that won’t affect the BOP current account except to the extent that national savings or domestic investment change.

LikeLike

You haven’t convinced me, Paul, when you say:” … if I’m selling someone has to be buying my NZ$1. Why are they buying, what can they do with a NZ$1?

This “someone” buyer may well be a trader who exchanges the $NZ1 for a $US1, or might be another Aussie who thinks “blow, the Kiwi is trending down, I’ll get out” and buys back Australian dollars.

Accepting what others pointed out above,it seems to me as a layman that the nominal amount of NZ dollars may stay the same, but if sellers outnumber buyers the NZ dollars’ total buying power, the value, falls. Wouldn’t basing foreign investment decisions on the point that NZ dollars, in total number on issue, would be unaffected, be tenuous?

Perhaps Michael Reddell could get a debate rolling sometime on economics itself. Some economists appear so certain in their views. I would like NZ experts to defend some of the core assumptions of economics, like the “rational man” who seemed to be certified less than fully rational by Daniel Kahneman, the psychologist and economist who won the 2002 Nobel prize for economics.

Michael Reddell is not one of these unassailables. He brings his economic views to us lay folk in a very readable and open style. Good stuff, Michael, please keep writing it for us.

LikeLike

“This “someone” buyer may well be a trader who exchanges the $NZ1 for a $US1, or might be another Aussie who thinks “blow, the Kiwi is trending down, I’ll get out” and buys back Australian dollars”

You can only sell if somebody buys. If a trader sells the NZ$ for US$s, why did the buyer at that point buy the NZ$? What can he do with it? The only thing he can do is buy something from NZ.

If people are getting out of the NZ$ then why is anyone buying? If somebody is buying it’s because they want something from NZ.

LikeLike

That is why we export high pollution products and offer mega tourism services. It creates a market value for the buying of NZD. You need people buying NZD so that I can go on my regular holidays where I can sell my NZD and get a nice cheap european holiday overseas. It does not help me if foreign owned NZ companies are busy selling NZD shipping their profits offshore while I am busy selling NZD as well for my holidays.

LikeLike

Is Apocalypse Cow or Apocalypse Now the pop-culture reference that you weren’t familiar with?

I guess the question is given the government created Fonterra is there any appetite to create a structure that is fit for purpose for the original intent?

If so what would such a structure look like?

LikeLike

Apocalypse Cow was apparently the name of an episode of The Simpsons and also “A comedic/parody action platform game spoofing other video games and movies”. There is even a book https://www.amazon.com/Apocalypse-Cow-Michael-Logan/dp/1250032865.

The things one stumbles onto…..

On the substantive question, one key issue is that – having been created – Fonterra is the property of its members, not the rest of us. In my view, policy should focus where there may be legislative/regulatory distortions that may be adsversely affecting others elsewhere in the economy (as Peter argues is the case). More generally, I think govts should stay out of “industry policy” – they are typically v bad at it, and have all the wrong incentives. On which note, see my post later this morning….

LikeLike

I was actually referring to the Francis Ford Coppola film.

It was 40 years since that was released and 20 years since the mega merger propsal so seemed apt.

LikeLike

I assumed you probably were. I was just intrigued by the various other uses of Apocalypse Cow I stumbled on.

LikeLike

“Peter is a former public servant – we did some work together, the last time Fonterra risks were in focus, a decade ago – who now operates as a consultant to various participants in the dairy industry (not Fonterra).”

Ah..that tells us a lot where Mr Fraser is coming from. The Fonterra bashing serves the interests of the presumably Chinese owned companies he advises for. All this talk of failure of Fonterra, but the only opinion that matters is that of the owners, the farmers and they seem satisfied enough. Forecast payout on milk solids is up again this year isn’t it? Some of the analysis trying to compare Fonterra to Synlait (a small newish niche company) and Nestle is laughable.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Fonterra bashing is really Fonterra’s own doing making some really really bad investment decisions.

LikeLike

“the only opinion that matters is that of the owners,”

That isn’t so if the rest of the industry is adversely affected by the relevant legislation rules. Or if the situation is going to deteriorate further and govt intervention become called for.

And while there is no perfect benchmark, there is no standard by which Fonterra has lived up to the promises from 20 years ago, or by which the investment returns to outside shareholders have been even marginally attractive.

I don’t know which players Peter works for, but I’d be surprised if the Chinese interests were front and centre – it would be in the interests of those players to let the situation drift, and not have attention called to the problems until it is “too late”.

LikeLike

Barry,

I can assure you that I do not work for any Chinese owned dairy or food company.

The closest I have gotten to this was between 2011-12 I was the economic advisor to three independent dairy companies; namely Open Country, Miraka, and Synlait.

Synlait did, and still does, have significant investment from Bright Dairies.

I have not worked for Synlait – either directly or as part of a group, for seven years.

I therefore think you may like to rethink your comments.

LikeLike

Few things:

1 – We all have to get away from the idea that Fonterra is a ‘national champion’ which deserves out adoration. As Fraser points out it is a private club that acts in the best interests of its members; no matter how mis guided one might thing they are.

2 -To be successful in the value added space you need to have the customer to sell two. There are plenty of people with fine ideas to build dairy processing in NZ, but most have fallen away because they didn’t have the customer. Synlait has been successful because it managed to get a customer.

3 – New Zealanders don’t really want to invest in the dairy processing sector it would seem as it is hard work and the customer is the problem. Yili can do the deal on Westland (a failed business) simply because it has the cash and the customer to buy the products – Yili really is the customer. It is far better to have Westland owned by someone and operated than to have it crash and burn into receivership.

4 – I am ambivalent about foreign investment. The capital has to come from somewhere and as a country we are well short of capital and good people to develop these business. Dairy processing is very capital intensive and there are more than just Chinese buying into the NZ Dairy processing chain. The Chinese are there to be sure because there is a huge demand from that country for NZ dairy products… let them come and develop these businesses we are all better of because of it.

5 – As to the complaint about dividends… grow up. Its the money that accrues to the shareholders after everyone else has been paid – its legally their money and they have a right to it. The size of any dividend paid depends on the opportunities a company sees, legal requirements and a host of other things.

LikeLike

“Guerrilla economist Peter Fraser warns the proposed sale of Westland Milk Products to an offshore buyer is just a “dress rehearsal” for a potential sale one day of Fonterra to a foreign buyer”.

Can never happen. Something has to happen.

Should Fonterra ever become foreign owned, the structure would not be a farmer driven co-operative. The very first thing new owners could and would do would be to reduce the price paid to farmers for their milk. Could they cut the price down to $4 per kg/MS. Possible. Why not? That would cause severe consternation among the dairy farmers and their bankers who currently fund $60 billion of debt. The current $6+ payout is needed to service the bank debt. Five years ago I did an analysis and found Normal on-farm operating expenses are around $3 per kg. Overheads and interest are substantial

A large reduction in the payout would cause a cascade effect from farm to banks to government heart attack.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on The Inquiring Mind and commented:

Excellent post with some serious issues to think about

LikeLike

If Fonterra wasn’t setting a price some regard as ‘too high’ farmers would be at the risk of a price that got lower and lower until they were forced off their farms as happened in Australia.

Other companies would love Fonterra’s price to be lower because they could then pay their suppliers less.

LikeLike

[…] Apocalypse Cow – Michael Reddell: […]

LikeLike

Fonterra share units close down today at $3.55

LikeLike

At the same time, the Vegetarian “Beyond Meat Inc” company, maker of fake meat, jumps up in value from a listing IPO price of US$25 a share to a high of US$65.

I think it is about time we start to recognise that Fonterra and milk production and our primary meat production industry are twilight niche industries, cash cow phase of a business life cycle but on the verge of disappearing.

LikeLike

Liked to post. It is quite amazing how things look from the outside. I guess economist have their agendas too.

I don’t think it is fair to compare Fonterra with Nestle and Danone (what economist always do to attack Fonterra). They are completely different. The former is in the middle of nowhere, with no domestic market (more on this below) and owned by farmers with no subsidies. The European companies are food companies in the middle of Europe, privately owned and buying from farmers supported by subsidies. Do you really expect to perform similarly?

Fonterra domestic market is regulated by law, it has to sell milk AT COST to it main competitor (Goldman Fielder) therefore is 100% reliant on making $ overseas.

Not going to argue about the management mistakes of the last 5-10 years, they are well documented. But foreign owned or Open Country alternatives are way worse for the country.

LikeLike

Thanks for the comments. I was interested in your comment on comparators. I’m not entirely sure what the best comparator is, and perhaps one needs to look at various comparisons, but it is hard to see a 40% fall in share price over seven years – in a rising global market – as a good performance. The other example Peter often highlights is Kerry in Ireland – on a quick check, its share price appears to have tripled since about 2011.

Perhaps the key thing worth remembering from an outside investor perspective is that they had a choice among each of these companies, and many more. Their expected returns back in 2012 would, presumably have been similar to expected returns for those other companies. It is just that actual returns didn’t live up to that expectation.

(I mostly stay clear of specific DIRA issues as my wife is a senior policy manager at MPI – not on dairy.)

LikeLike