That is the title of a new paper, intended (it appears) to inaugurate an annual series, from the Productivity Commission. It is full of interesting tables and charts, and usefully drives home the point – made repeatedly on this blog, and elsewhere – that (a) longer-term productivity growth in New Zealand has been poor, and (b) that productivity growth matters for all sorts of other things New Zealanders individually or collectively care about.

Productivity growth in New Zealand has lagged since at least the 1950s. On the data we have, the worst decade (falling further behind) was the 1970s, but the Productivity Commission usefully highlights that we have on slipping even in the last couple of decades. This is one of their charts, showing the level of labour productivity in 1996 (about when the full OECD data series starts) and growth in productivity since then.

Broadly speaking, the cross-country story has been one convergence: countries with lower initial productivity catching up (top left quadrant) and those with higher initial productivity growing more slowly (bottom right quadrant). There is only one country in the top right quadrant (Ireland), but that is substantially a measurement issue stemming from the corporate tax rules.

But, as the Commission highlights, New Zealand is in the bottom left quadrant: countries that had only modest productivity levels in 1996, and still managed to grow slowly in the subsequent decades. The real basket-case is, of course, Mexico, but we find ourselves grouped with Portugal and Greece, and Israel and Japan (as I’ve noted here previously, it is well past time people in New Zealand stopped talking of Israel as some sort of high-growth exemplar).

I like the chart, and I’ve highlighted here previously the contrast between the productivity growth performance of the central and eastern European OECD member countries (top left) and New Zealand, including noting that several of them now have productivity levels very similar to those in New Zealand and are still growing fast. I dug out the data for a similar chart going back to 1970 (when the OECD database begins, but for a smaller sample of countries). Over that full period, we stand out as the underperformer.

But the Productivity Commission does rather tend to pull its punches (they are a government-funded agency, and depend wholly on (a) the resources the government allocates to them, (b) the quality of the Commissioners governments appoint, and (c) the character of the issues governments invite them to investigate). (On (b) it seems somewhat overdue for the government to announced a replacement for now-departed former Secretary to the Treasury, and highly-regarded economist, Graham Scott, who has served as a Commissioner since the Productivity Commission was founded).

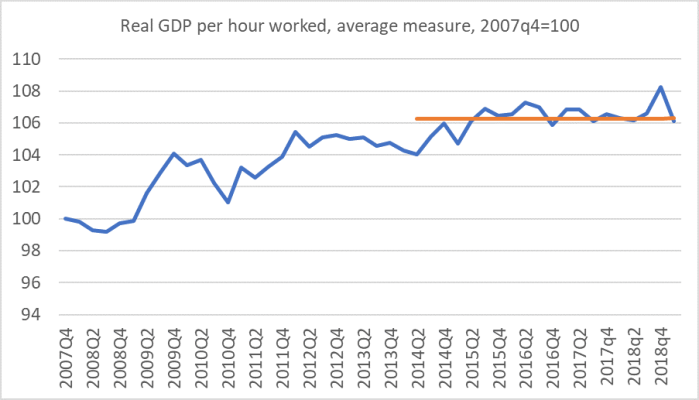

Pull its punches? Reading “Productivity by the Numbers” you would have no idea how absolutely poor our labour productivity performance had been over the last few years.

And there is, therefore, no sense of what light this experience might shed on possible explanations for our continued long-term underperformance.

They are also a bit self-promoting, suggesting that reversing the productivity underperformance “has been a central theme of the Productivity Commission’s work since 2011”. If anything, the opposite has been true. The Commission research team (when led by the now-departed Paul Conway) has at times produced some interesting papers on the issue, but the Commission’s core work is the inquiries successive governments have asked them to undertake, and not one of those inquiries has had as its focus economywide productivity failures and challenges. Some of the inquiries have led the Commission down pathways which can, at best, be described as limiting the (economic) damage – eg the low emissions inquiry. On the other hand, the Commission has done a (mostly) positive job in helping to develop a more widely shared recognition that land use regulatory restrictions (and associated infrastructure financing perhaps) are at the heart of the housing disaster successive central and local governments have presided over for the best part of three decades.

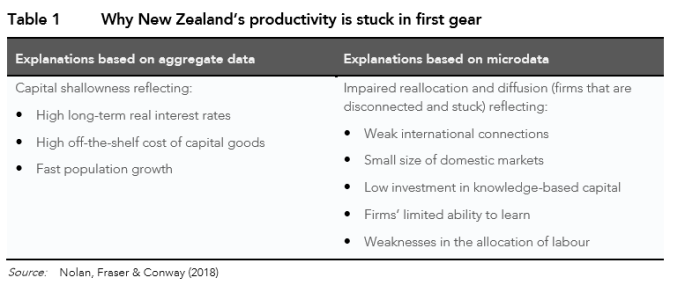

“Productivity by the numbers” is mostly descriptive – tables, charts, and comments thereon – but the authors do weigh in a little on possible explanations. They include this table, taken from another recent article

A couple of the items in the left-hand column are clearly intended as a nod in the direction of my ideas (referenced in the article the table is drawn from), and I welcome that. But it isn’t clear that the Commission – let alone the government’s official departmental advisers – is even close to a current integrated and persuasive narrative of what has gone wrong and how, if at all, things might be fixed. As is perhaps inevitable in a summary table, many of the items are at best stylised facts (some probably not even facts).

The report goes on

This work has highlighted that New Zealand’s poor productivity performance has been a persistent problem over decades and turning this around will require consistent and focussed effort over many fronts and for many years. There is no simple quick fix.

It is a convenient line – especially as there is no political appetite for change anyway – but I don’t believe it is true. Sure, we aren’t going to close the productivity gaps overnight, and sure there are (always) lots of useful reforms that could make a difference in a small way. But here we aren’t dealing with the small differences between, say, productivity in the Netherlands and that in Belgium. For an underperformance as large and as sustained as New Zealand’s – in what is substantially a market economy with passable institutions (rule of law etc) – it is highly likely that there are (at most) a handful of really important policy failures (things done or not done) where most of the mileage from reform would be likely to arise. And there the Commission just does not engage. Instead it tries to move on to a more upbeat story, and to shift the “blame” onto the private sector.

Indeed, work is already taking place in many areas, including in competition policy, infrastructure, science and innovation, and education and the labour market. There is growing interest in the need to improve Kiwi firms’ management practices and ability to learn (absorptive capacity), which shape their ability to innovate and improve their productivity (Harris & Le, 2018).

To me, much of this seems like dreamland stuff, deliberately choosing to avoid hard questions, while flattering the egos of ministers and officials in Treasury or MBIE. Whatever the Productivity Commission thinks is good among those topics in the first sentence (and I struggle to think of anything much), it isn’t credible to suppose that the things they like about current policy even begin to make the sort of difference required to reverse the productivity failures. And much as officials and academics like to suggest there is something wrong with New Zealand businesses (convenient that), there is no evidence that New Zealand firms and employees (managers and others) would be any less able to identify and respond to opportunities if government roadblocks and obstacles, including distorted relative prices, were fixed.

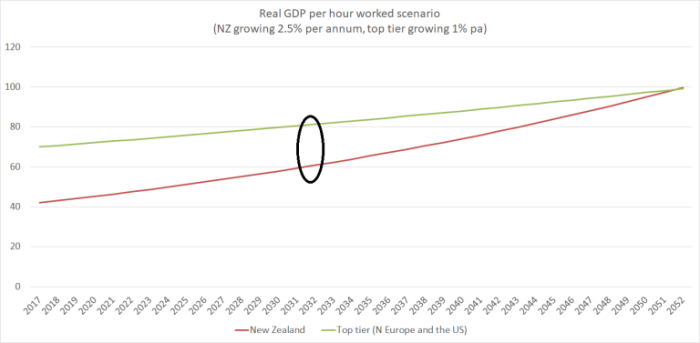

In the report, the Productivity Commission highlights how much we will miss out on if productivity growth continues to underperform the (somewhat arbitrary) 1.5 per cent per annum growth assumption in Treasury’s medium-term fiscal model. The point is that small differences compound in ways that make for big differences in material living standards and opportunities. And on that count I totally agree with them. I made a similar point the other way round in a post on productivity last year.

I’ve banged on here about how dismal productivity growth in New Zealand has been in the last five years in particular. The best-performing OECD countries over the most recent five years were averaging more than 2 per cent productivity growth per annum – and all of them were countries catching up with the most productive economies, just as we once aspired to do. If we’d managed 2 per cent productivity growth per annum in the last five years, per capita GDP would be around $5000 per head higher (per man, woman, and child) today.

Catching up to the top tier will, in a phrase from Nietzche, take a “long obedience in the same direction” – setting a course and sticking to it. But here is a scenario in which the top tier countries achieve 1 per cent average annual productivity growth, and we manage 2.5 per cent average annual productivity growth. Here’s what that scenario looks like:

I’ve marked the point, 15 years or so hence, where the gap would have closed by half.

I don’t usually quote Nietzsche, but here is the full quote

“The essential thing ‘in heaven and earth’ is… that there should be a long obedience in the same direction; there thereby results, and has always resulted in the long run, something which has made life worth living.”

What matters in an economy like New Zealand now isn’t finding 100 or 300 things to reform – sensible as many of them might be – but finding the one (or two or three) things that might make a real difference, adjusting policy accordingly, and then persevering long enough to start seeing real and substantial results. There is no reason why New Zealand should not again manage something close to top tier OECD average labour productivity, but – on the demonstrated – there is no reason to suppose that (a) anything like the current policy mix will deliver it, or (b) that tiny changes at the margin will deliver very substantially different results. Welcome as the Productivity Commission’s statistical compilation is, those are the messages that need to be heard more loudly.

Sadly, of course, not a single political party seems to have any appetite for reversing our decades of economic decline. But, just possibly, a compelling narrative from an authoritative body like the Productivity Commission might one day begin to change that. At present, instead, the Commission seems in some unsatisfactory place where they don’t have the answers, and to the extent they sense some elements of an answer, they don’t want to upset anyone.

“There is no reason why New Zealand should not again manage something close to top tier OECD average labour productivity”

This seems to contradict some of your other narrative about NZ’s distance to markets, and other impediments to growth. Care to expand?

LikeLike

Yep, no reason why we shouldn’t be close to top-tier – despite distance – so long as we stop using policy to drive up population rapidly. Natural resources are a fixed resource, and altho we can do more with what we have, experience of recent decades suggests we can’t do it with lots and lots more people (while our own people have responded to market signals and left).

Of course, probably better if we’d levelled off at 3m people, but level off where we are (5m) with a birthrate below replacement, and in 25 years we’d have closed a lot of the gaps.

NB I’m not saying we can realistically match or exceed the top-tier OECD group (France, Germany, Sweden, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, US) in my lifetime, given choices already made. Over 100 years, who knows – superior policy (which we don’t have now), flat population, perhaps new technologies really do become the death of distance, who knows. But we should respond to the world as it is, not as we might like it to be.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Every country in the world sells its products in NZ. Distance to NZ has not been a problem to anyone else around the world. Seems rather far fetched that it is only a problem for NZ economists.

LikeLike

Completely different issue. Of course people from abroad can sell stuff here, and transport costs aren’t the biggest issue. The issue is whether many outward-oriented businesses, not based on fixed natural resources, can find NZ the most profitable/best location for selling to the rest of the world. Experience suggests not, to date. We have plenty of smart people with good ideas. But even when they overcome the hurdles to get established, the resulting business is usually more valuable when based (typically owned) elsewhere.

LikeLike

Michael, so essentially what you are saying is that it is not anything to do with distance but with the access to the size of the market. What is the variable then? Population size or distance? No wonder NZ economists cannot forecast with any degree of accuracy if you can’t even properly identify the variables.

LikeLike

Here is an example where less people may have made us more productive (perhaps)

The tourism boom is destroying our best destinations. Can anything be done to fix it?

And is there somewhere that gets it right? “Switzerland. They know exactly who they are and that’s what they promote.” We talk about Zermatt, near the Swiss alpine border with Italy, which bans cars and only has horses in the middle of the town. It’s a tourists’ dream come true. “And they have this bloody great car park right out of town,” says Budd, “where everyone has to leave their car. Then the hotel sends free electric powered shuttles to pick them up.” It’s a misty-eyed vision of what Queenstown could have been. “They’ve also got bloody good roads and bloody good trains,” he adds. “If I had a vision for Queenstown it would be exactly that.” The phrase ‘reassuringly expensive’ pops into my head.

https://thespinoff.co.nz/society/11-05-2017/the-tourism-boom-is-destroying-our-best-destinations-can-anything-be-done-to-fix-it

Warren Cooper believed the market was the best and only way to decide Queenstown’s future.

LikeLike

You mention “the one (or two or three) things that might make a real difference”. Got a short-list?

LikeLike

Indeed.

The first, and most important, item, would be to slash our annual migrant intake (residence approvals) to something like 10-15K per annum (as it happens, in per capita terms that would reduce to around current US rates) and keep it low. My narrative is that the biggest single failing of policy has been to pull more and more people into a location which, it turns out, is much less propitious than was generally appreciated (eg the failure of new non-natural resource based tradables industries to grow here).

Second, and well behind, would be to materially lower the rate of tax on business investment (especially, as it happens – because of imputation – foreign investment). Doing so would both substantially lower many business costs – much of our foreign investment is in the non-tradables sector – but would also materially increase prospective returns to new tradables investment, reinforcing the gains offered by a lower real exchange rate (resulting from the reduced population pressure on non-tradables).

We also need to fix/overhaul the RMA. I don’t buy the line that fixing the urban property market will materially boost productivity – and in my world, I expect the provinces to do better relative to Akld – but (a) fixing housing is part of an overall package, and a justice cause in its own right, and (b) the RMA isn’t only about urban land, and (see 1 and 2 above) reform will partly involve a better environment for outward-oriented business investment.

LikeLike

Your most important item is human population. Making it an issue of migrants only is wrong. Those who are pro-immigration point out migrants arrive at their most productive age and they cost NZ taxpayers nothing for their education. The numbers emigrating often swamp the migration numbers. Is emigration a good or bad thing for NZ productivity? Sometimes it is our brightest and most energetic and sometimes the uneducated new Zealander realising a manual worker in Qld may be able to buy a house but they never will in Auckland.

Any change to migration numbers will take years to make any difference to productivity – but a dramatic reduction might quickly reduce house prices and that could persuade our ambitious young to stay.

LikeLike

I disagree with your emphasis. The population of NZers is not a policy variable, but additions to the non-citizen population are. I will never asssociate myself with arguments that could be used in support of a view – taken by some Greens – that govts should have a view on whether couples should have fewer children.

On the substance, the real exchange rate could be expected to adjust quickly and substantially to a credible and substantial long-term change in immigration policy.

LikeLike

I suspect we agree; I certainly disagree with those arguments I listed made for immigration. A good society values children and in other forums I propose increasing income tax so the govt can afford to pay a generous universal child benefit – it is a view that never gets any traction.

My point is that dollars and people are different. When an economist writes about wealth produced per capita per hour it is something measured in NZ dollars and rightly makes no distinction between a dollar tax earned by a legal brothel or a dollar of earned by say Xero’s software. No moral judgement since that dollar can be taxed and used by the govt for a good purpose – say funding medicine for handicapped children. People are different but your article treats them as homogenus.

If there are opportunities for increasing producivity then it will require not just a reduced number of people but suitably skilled people focused on productive activities with strong ties to NZ. NZ already has such people and only very rarely actually needs an immigrant.

LikeLike

Frequently you mention ‘real exchange rate’ and I look it up and it makes sense until I forget why. Are there examples that prove strong linkage between real exchange rate and productivity?

LikeLike

Yes and no. Countries with rapid productivity growth all else equal tend to have appreciating real exchange rate (for good theoretical and practical reasons), but countries that are catching up often do so thru a process that involves a sustained period of a weak real exchange rate (stylised story for China, Japan, South Korea, Singapore) supporting the expansion of an export-oriented economy, where firms prove themselves in world markets, develop the skills, incl mgmt skills, to compete aggresively.

LikeLike

Hi Michael

What specific things would you do to fix/overhaul the RMA? Is it mostly in the land scarcity domain?

I’m looking at some of the literature around water-related bits of the Act and predecessors, and (I know it is probably not your main concern) but it is a serious knot. Even the concept of a ‘fix’ seems off in that area to me because whatever the words on the page of the statute book, I’m not sure that the underlying agreed set of values is there.

Thanks

LikeLike

Re housing, it seems to be mostly a land scarcity issue. I would like to see a presumptive right to build houses ( at least to 2 or 3 storeys) written into legislation, but on technical details i’d Be guided by people closer to specifics. Re water etc, yes quite take your point about the potential importance.

LikeLike

The Auckland Unitary plan does offer a minimum 2 dwellings and more, higher density options on all residential dwelling zones. The only requirement is a Outlook space of around 25sqm which is the size of a double garage as a sort of living space.

What is holding me back from proceeding with a development is the cost of services and a corrupt culture with the development and the entire building process with Council Officers and with private contractors. In NZ the corrupt culture is not money under the table but money over the table through intentional delays. That can take the form of dropping important key components out of a quote or intentional damages that they have to fix but can’t be blamed for, and council inspectors that are purposely inconsistent with their standards.

LikeLike

My impression and one that, in the Nietzsche tradition I have held for some years, is that New Zealand has moved from being an ‘added value’ exporter to a ‘commodity’ exporter. In addition we have reduced the quantity of ‘added value’ to our imports.

LikeLike

Good article. Note, Israel is an exceptional economy unlike NZ with its back woodsmen farmer. Israel is in fact world leaders in developers of agriculture, computer, solar, security, optics, game theory, biotechnology and medical technology but they have had to spend a large part of GDP on defense. They have also absorbed many new immigrants from Russia that required significant state funding.

LikeLike

Defence is a consumption item, and shouldn’t really affect average productivity levels. But your final sentence is where the nz and Israel stories really overlap – both countries have taken really large numbers of migrants, and in both countries there is no sign that large scale immigration (now) is productivity enhancing.

LikeLike