In the last few weeks, presumably simply by coincidence, I’ve had various comments and emails about productivity growth in the agricultural sector. The most recent one finally prompted me to dig out the official data and check that my impressions were still supported by the data. They were. Agricultural sector productivity growth was very strong, but has been much more subdued for some time now.

There are two main measures of agricultural sector productivity: labour productivity (in effect, output per hour of labour input) and multi-factor productivity (in effect, the residual after what can be attributed to growth in labour and capital inputs has been deducted). In principle, MFP is superior. In practice, estimates rely more heavily on the assumptions used in the calculation (although – diverting briefly – to the various readers who have sent me a recent piece by GMO on TFP/MFP, I reckon there is less to that critique than the authors claim).

Agriculture is one of the sectors for which we have consistent productivity data back to year ending March 1978. By New Zealand standards, that is a long run of data. Note that there is quite a bit of natural volatility from year to year because of fluctuations in the climate (droughts and all that).

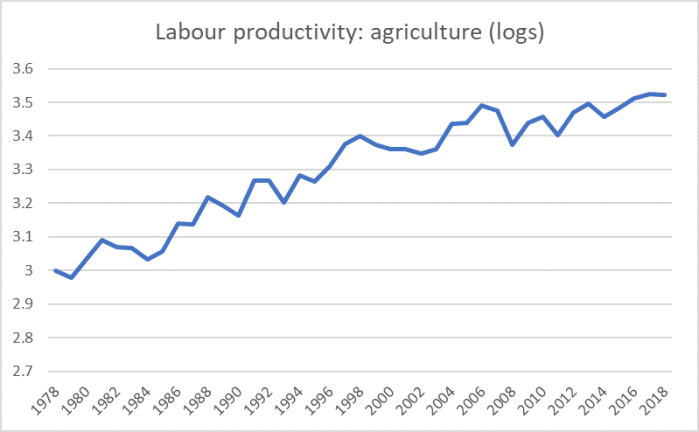

Here are the charts showing growth in labour productivity and in multi-factor productivity (both expressed in log terms, so that the slope of the line indicates the growth rate).

Really rapid growth in the first 20 years or so (up 150 per cent in 20 years), but much slower growth since then. It isn’t disastrous growth by any means – averaging just under 1.5 per cent per annum from 2005 to now – but nothing startling either.

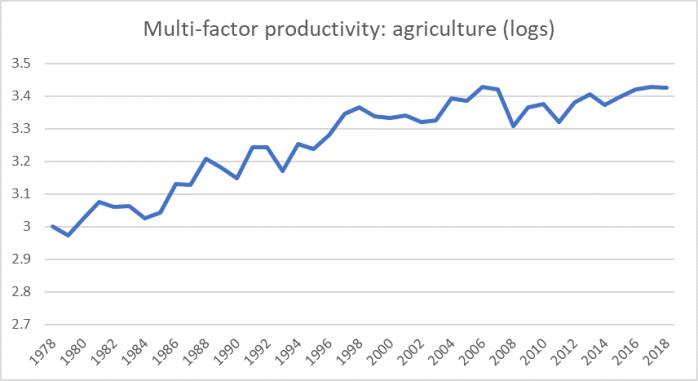

And MFP.

Once again, really strong productivity growth for the first 20 years, and much less since then (none at all in the last decade). If one had confidence in the data, that might be more concerning.

Perhaps – and it is an obvious question to ask – you are wondering if the slowdown in agricultural productivity growth is just part of the general slowdown in labour productivity growth in New Zealand (seen mostly starkly in the overall economy figures, where there has been very little growth at all in the last five years or so).

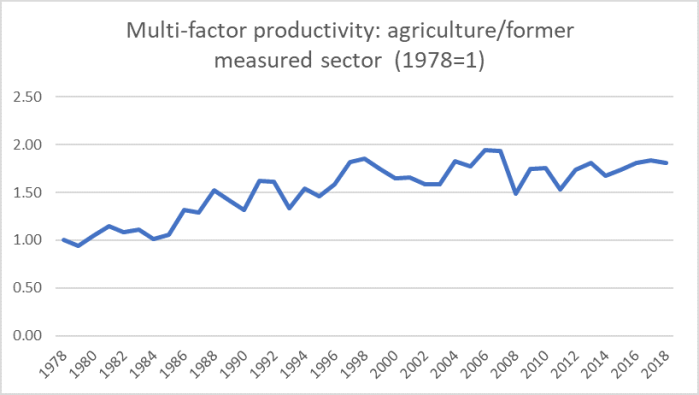

So here are the same two charts – labour productivity and MFP – but this time showing agriculture relative to the overall “former measured sector” (the series SNZ publishes that also goes back to 1978, covering the 70 per cent or so of the economy where productivity is relatively less hard to measure). All series are indexed to a common base in 1978 (so none of this is about productivity levels, it is all about cumulative growth rates).

Labour productivity first.

and MFP

There is clearly something in the story. Growth in the “former measured sector” productivity itself has slowed – labour productivity growth averaged 2.4 per cent from 1978 to 1998 and 1.6 per cent for the 20 years since 1998. But whereas agricultural sector productivity growth was (far) outstripping that in the rest of the “former measured sector” in the earlier years – the upward-sloping bits of the last two charts – in the last 20 years (and even more so in the last 10) productivity growth in the agricultural sector has been a little slower than in the rest of the “former measured sector”.

I don’t have a policy point to make here. Sector-level productivity isn’t my area. Relative optimists might look at the data and suggest liberalisation played a big part in the earlier productivity surge, and that liberalisation wasn’t ever going to be repeated. Perhaps, but bear in mind that our agricultural sector was always the part of the economy most heavily exposed to international markets (by contrast, a sector like “Transport, postal, and warehousing” – with similar total labour productivity growth over 40 years – was almost certainly much more sheltered). Pessimists might focus on the role of unpriced externalities (particularly around water pollution, but also methane emissions) and wonder how agricultural sector productivity might respond as regulation bears more heavily there (although it is possible we could see higher average productivity and lower total output). Others might reasonably wonder about these productivity measures for agriculture in particular: in most sectors labour and capital are the critical inputs, but land is a huge input in agriculture and it isn’t directly accounted for (something which matters – much – more in looking at levels estimates). [UPDATE: A SNZ person got in touch and pointed out that they do take account of land in their capital services estimates.]

As for me, my only motivation was to update my impressions. Sadly, the latest data confirmed them.

The issue being agricultural productivity increased rapidly and then plateaued and if we knew why it would help predict what will happen next.

These are my city dweller’s theories.

1. The big gains based on the application of scientific to agriculture will be at the beginning and progressively reduce (similar to athletic world records)

2. Technology has led to a dramatic reduction in labour but this was achieved about 20 years ago so it is now hard to further reduce labour costs

3. Technology has led to a dramatic reduction in labour which in turn leads to an elderly work force (as I saw with British Railways during the 60s and 70s). A wiser but older farmer may reduce stocking rates so he spends fewer winter nights with lambing. He may also be less likely to risk borrowing capital from banks to invest in his business than a young farmer.

4. Expansion of tertiary education – the typical above average teenager now sees more status in studying communications or psychology or gender studies or economics than actually producing food. Only the most determined proto-farmers and the rather dumb unable to attain Uni entrance will enter a sparse, elderly workforce. If most of the new farmers are kids with low mental ability then productivity will not increase.

I am still rather surprised that productivity is not increasing faster than shown because:-

1. Agriculture is where the money is and traditionally always has been

2. Very useful technologies have been introduced in the last decade: drones, satellite photos showing moisture levels, long term weather prediction, use of mobile phones saving visits by vets, internet access to latest market prices, improved fertilisers, etc.

3. Cheap [exploited immigrant] temporary contract labour for fruit picking and other seasonal tasks

4. Increasing number of foreign owned and abscent owner farms; a manager with staff will never be as productive as a well run family farm.

Hopefully rural contributors will tell me where I am wrong.

LikeLike

It’s called the “Law of Diminishing Returns”

Over the last 20 years we have seen the size of farms increase by way of accumulation and aggregation. When the farm next door becomes available for sale the farmer buys it thus increasing production and achieving economies of scale. That works until the economies of scale stop working and start going backward.

We live on a rural property. The property next door to us of 270 hectares came up for sale two years ago. A corporate farmer purchased it. The house on the property is rented out to a family who don’t work on the farm which is used for running sheep and fattening cattle. The new owner is old-money. They are running and manage 3000 hectares spread over many farms spread over long distances.

Since being sold the farm next door has been poorly managed. It is not looked after. They deliver stock, drop them off and then disappear. The property is slowly deteriorating. The number of stock units is dwindling. It is run to the lowest cost which will be less than the previous owner achieved, but the yield is much less

From my observation farming is in a bigger-size-is-better phase regardless of the economics. The productivity curve flattening off is a reflection of weather and economies of scale plateauing

Secondly climate change has seen dramatic impacts on the weather. Where we are there has been no rain. The fields are browned off and there is no grass feed. Been that way for the last 5 years. Intensive farmers have to buy baleage in or but imported PKE. The price of a bale of fluctuates between $70 and $100 depending on the weather and supply

LikeLiked by 1 person

It looks like New Zealand’s dairy sector is riding to the economic rescue – again.

Global dairy prices have bounced up from a cyclical low in November. After the latest global dairy auction they are broadly up about 23 per cent. That’s a relief because however gloomy business confidence might be in downtown Auckland, it’s hard to see GDP growth dipping too much with a Fonterra dairy payout closing in on $7/per kg of milk solids. As ANZ’s commodity index shows, beef, lamb, kiwifruit and logs are all in pretty good shape.

https://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/news/article.cfm?c_id=3&objectid=12210362

Liam Dann’s propaganda does not mention that farmers contribute less than 5% of the governments tax revenue. Also the fact that we have reached peak land use and therefore the Law of Diminishing returns apply.

We have run out of room due to intensive farming to the extent that we now consider 5 million kiwis on land the size of Japan (with 123 million people) as too many people. PKE or Palm Oil Kernels is not exactly a very green animal feed.

LikeLike

[…] Agricultural sector productivity growth – Michael Reddell: […]

LikeLike