On various occasions previously, I’ve used here survey results from the IGM Economic Experts panel, run out of the University of Chicago Booth School. They survey academic economists in the US and Europe and the results often shed some interesting light on consensus, and difference, within the academic economics discipline. As ever of course, much depends on how the questions are framed.

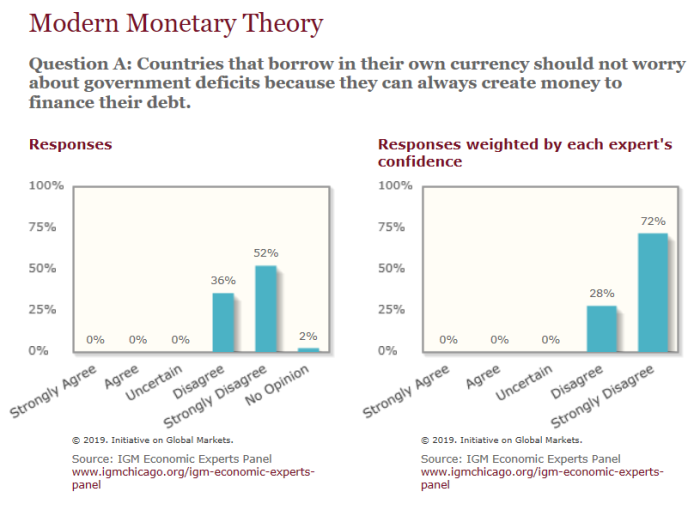

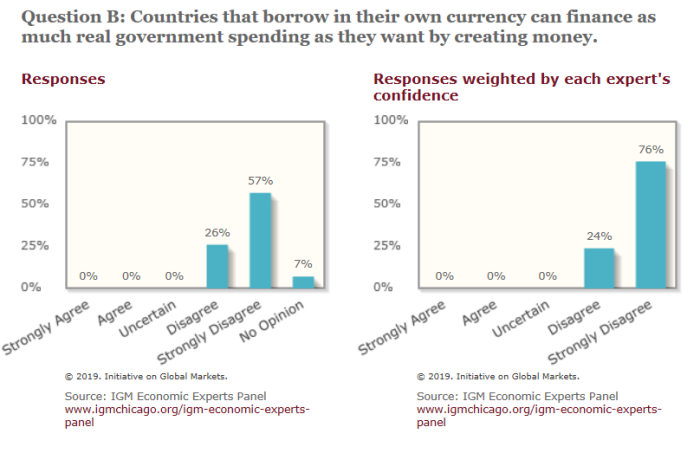

Their latest effort was not one of their best. There were two questions.

Glancing through the individual responses, if there are differences among these academic economists they seem to be mainly ones of temperament (some people are just very relucant to ever use either 1 or 5 on a five point scale).

But so what? No serious observer has ever really argued otherwise.

So-called Modern Monetary Theory has been around for some time, but has had a fresh wave of attention in recent weeks in the context of the so-called “Green New Deal” that is being propounded by various more or less radical figures of the left of American politics. Primary season is coming. The brightest new star on that firmament, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, has associated herself with the MMT label.

One of the more substantial proponents of MMT thinking, Professor Bill Mitchell of the University of Newcastle, visited New Zealand a couple of years ago. I wrote about his presentation and a subsequent roundtable discussion in a post here. We had a bit of an email exchange after he stumbled on my post, and although we disagree on policy, I was encouraged that he thought my treatment had been “very fair and reasonable”. I mention that only so that in the extracts that follow people realise that I’m not describing a straw man. I don’t know how Professor Mitchell would have answered the IGM survey questions above, but what I heard that day in 2017 should logically have led him to join the consensus. That’s a mark of how useless the survey questions were.

He seemed to regard his key insight as being that in an economy with a fiat currency, there is no technical limit to how much governments can spend. They can simply print (or – since he doesn’t like that word – create) the money, by spending funded from Reserve Bank credit. But he isn’t as crazy as that might sound. He isn’t, for example, a Social Crediter. First, he is obviously technically correct – it is simply the flipside of the line you hear all the time from conventional economists, that a government with a fiat currency need never default on its domestic currency debt. And he isn’t arguing for a world of no taxes and all money-creating spending. In fact, with his political cards on the table, I’m pretty sure he’d be arguing for higher taxes than New Zealand or Australia currently have (but quite a lot more spending). Taxes make space for the spending priorities (claims over real resources) of politicians. And he isn ‘t even arguing for a much higher inflation rate – although I doubt he ever have signed up for a 2 per cent inflation target in the first place.

In listening to him, and challenging him in the course of the roundtable discussion, it seemed that what his argument boiled down to was two things:

- monetary policy isn’t a very effective tool, and fiscal policy should be favoured as a stabilisation policy lever,

- that involuntary unemployment (or indeed underemployment) is a societal scandal, that can quite readily be fixed through some combination of the general (increased aggregate demand), and the specific (a government job guarantee programme).

Views about monetary policy come and go. As he notes, in much academic thinking for much of the post-war period, a big role was seen for fiscal policy in cyclical stabilisation. It was never anywhere near that dominant in practice – check out the use of credit restrictions or (in New Zealand) playing around with exchange controls or import licenses – but in the literature it was once very important, and then passed almost completely out of fashion. For the last 30+ years, monetary policy has been seen as most appropriate, and effective, cyclical stabilisation tool. And one could, and did, note that in the Great Depression it was monetary action – devaluing or going off gold, often rather belatedly – that was critical to various countries’ economic revivals.

In many countries, the 2008/09 recession challenged the exclusive assignment of stabilisation responsibilities to monetary policy. It did so for a simple reason – conventional monetary policy largely ran out of room in most countries when policy interest rates got to around zero. Some see a big role for quantitative easing in such a world. Like Mitchell – although for different reasons – I doubt that. Standard theory allows for a possible, perhaps quite large, role for stimulatory fiscal policy when interest rates can’t be cut any further.

But, of course, in neither New Zealand nor Australia did interest rates get anywhere near zero in the 2008/09 period, and they haven’t done so since. Monetary policy could have been – could be – used more aggressively, but wasn’t.

As exhibit A in his argument for a much more aggresive use of fiscal policy was the Kevin Rudd stimulus packages put in place in Australia in 2008/09. According to Mitchell, this was why New Zealand had a nasty damaging recession and Australia didn’t. Perhaps he just didn’t have time to elaborate, but citing the Australian Treasury as evidence of the vital importance of fiscal policy – when they were the key advocates of the policy – isn’t very convincing. And I’ve illustrated previously how, by chance more than anything else, New Zealand and Australian fiscal policies were remarkably similar during that period. And although unemployment is one of his key concerns – in many respects rightly I think – he never mentioned that Australia’s unemployment rate rose quite considerably during the 2008/09 episode (in which Australian national income fell quite considerably, even if the volume of stuff produced – GDP – didn’t).

On the basis of what he presented on Friday, it is difficult to tell how different macro policy would look in either country if he was given charge. He didn’t say so, but the logic of what he said would be to remove operational autonomy from the Reserve Bank, and have macroeconomic stabilisation policy conducted by the Minister of Finance, using whichever tools looked best at the time. As a model it isn’t without precedent – it is more or less how New Zealand, Australia, the UK (and various other countries) operated in the 1950s and 1960s. It isn’t necessarily disastrous either. But in many ways, it also isn’t terribly radical either.

Mitchell claimed to be committed to keeping inflation in check, and only wanting to use fiscal policy to boost demand where there are underemployed resources. And he was quite explicit that the full employment he was talking about wasn’t necessarily a world of zero (private) unemployment – he said it might be 2 per cent unemployment, or even 4 per cent unemployment. He sees a tight nexus between unemployment and inflation, at least under the current system (at one point he argued that monetary policy had played little or no role in getting inflation down in the 1980s and 1990s, it was all down the unemployment. I bit my tongue and forebore from asking “and who do you think it was that generated the unemployment?” – sure some of it was about microeconomic resource reallocation and restructuring, but much it was about monetary policy). But as I noted, in the both the 1990s growth phase and the 2000s growth phase, inflation had begun to pick up quite a bit, and by late in the 2000s boom, fiscal policy was being run in a quite expansionary way.

I came away from his presentation with a sense that he has a burning passion for people to have jobs when they want them, and a recognition that involuntary unemployment can be a searing and soul-destroying experience (as well as corroding human capital). And, as he sees things, all too many of the political and elites don’t share that view – perhaps don’t even care much.

In that respect, I largely share his view.

Nonetheless, it was all a bit puzzling. On the one hand, he stressed how important it was that people have the dignity of work, and that children grow up seeing parents getting up and going out to work. But then, when he talked about New Zealand and Australia, he talked about labour underutilisation rates (unemployment rate plus people wanting more work, or people wanting a job but not quite meeting the narrow definition of actively seeking and available now to start work). That rate for New Zealand at present is apparently 12.7 per cent – Australia’s is higher again. Those should be, constantly, sobering numbers: one in eight people. But some of them are people who are already working – part-time – but would like more hours. That isn’t a great situation, but it is very different from having no role, no job, at all. And many of the unemployed haven’t been unemployed for very long. As even Mitchell noted, in a market economy, some people will always be between jobs, and not too bothered by the fact. Others will have been out of work for months, or even years. But in New Zealand those numbers are relatively small: only around a quarter of the people captured as unemployed in the HLFS have been out of work for more than six months (that is around 1.5 per cent of the labour force). We should never trivialise the difficulties of someone on a modest income being out of work for even a few months, but it is a very different thing from someone who has simply never had paid employment. In our sort of country, if that was one’s worry one might look first to problems with the design of the welfare system.

Mitchell’s solution seemed to have two (related) strands:

- more real purchases of good and services by government, increasing demand more generally. He argues that fiscal policy offers a much more certain demand effect than monetary policy, and to the extent that is true it applies only when the government is purchasing directly (the effects of transfers or tax changes are no more certain than the effects of changing interest rates), and

- a job guarantee. Under the job guarantee, every working age adult would be entitled to full-time work, at a minimum wage (or sometimes, a living wage) doing “work of public benefit”. I want to focus on this aspect of what he is talking about.

It might sound good, but the more one thinks about it the more deeply wrongheaded it seems.

One senior official present in the discussions attempted to argue that New Zealand was so close to full employment that there would be almost no takers for such an offer. That seems simply seriously wrong. Not only do we have 5 per cent of the labour force officially unemployed, but we have many others in the “underutilisation category”, all of whom would presumably welcome more money. Perhaps there are a few malingerers among them, but the minimum wage – let alone “the living wage” – is well above standard welfare benefit rates. There would be plenty of takers. (In fact, under some conceptions of the job guarantee, the guaranteed work would apparently replace income support from the current welfare system.)

But what was a bit puzzling was the nature of this work of public benefit. It all risked sounding dangerously like the New Zealand approach to unemployment in the 1930s, in which support was available for people, but only if they would take up public works jobs. Or the PEP schemes of the late 1970s. Mitchell responded that it couldn’t just be “digging holes and filling them in again”. But if it is to be “meaningful” work, it presumably also won’t all be able to involve picking up litter, or carving out roadways with nothing more advanced than shovels. Modern jobs typically involve capital (machines, buildings, computers etc) – it accompanies labour to enable us to earn reasonable incomes – and putting in place the capital for all these workers will relatively quickly put pressure on real resources (ie boosting inflation). If the work isn’t “meaningful”, where is the alleged “dignity of work” – people know artificial job creation schemes when they see them – and if the work is meaningful, why would people want to come off these government jobs to take existing low wage jobs in the prviate market?

The motivation seems good, perhaps even noble. I find quite deeply troubling the apparent indifference of policymakers to the inability of too many people to get work. The idea of the dignity of work is real, and so too is the way in which people use starting jobs to establish a track record in the labour market, enabling them to move onto better jobs.

But do we really need all the infrastructure of a job guarantee scheme? In countries where interest rates are still well above zero, give monetary policy more of a chance, and use it more aggressively. For all his scepticism about monetary policy, it was noticeable that in Mitchell’s talks he gave very little (or no) weight to the expansionary possibilities of exchange rate. But in a small open economy, a lower exchange rate is, over time, a significant source of boost to demand, activity, and employment. And winding back high minimum wage rates for people starting out might also be a step in the right direction.

And curiously, when he was pushed Mitchell talked in terms of fiscal deficits averaging around 2 per cent of GDP. I don’t see the case in New Zealand – where monetary policy still has capacity – but equally I couldn’t get too excited about average deficits at that level (in an economy with nominal GDP growth averaging perhaps 4 per cent). Then again, it simply can’t be the answer either. Most OECD countries – including the UK, US and Australia – have been running deficits at least that large for some time.

It is interesting to ponder why there has been such reluctance to use fiscal policy more aggressively in countries near the zero bound. Some of it probably is the point Mitchell touches on – a false belief that somehow countries were near to exhausting technical limits of what they could spend/borrow. But much of it was probably also some mix of bad forecasts – advisers who kept believing demand would rebound more strongly than it would – and questionable assertions from central bankers about eg the potency of QE.

But I suspect it is rather more than that – issues that Mitchell simply didn’t grapple with. For example, even if there is a place for more government spending on goods and services in some severe recessions, how do we (citizens) rein in that enthusiasm once the tough times pass? And perhaps I might support the government spending on my projects, but not on yours. And perhaps confidence in Western governments has drifted so low that big fiscal programmes are just seen to open up avenues for corruption and incompetent execution, corporate welfare and more opportunities for politicians once they leave public life. Perhaps too, publics just don’t believe the story, and would (a) vote to reverse such policies, and (b) would save themselves, in a way that might largely offset the effects of increased spending. They are all real world considerations that reform advocates need to grapple with – it isn’t enough to simply assert (correctly) that a government with its own currency can never run out of money.

I don’t have much doubt that in the right circumstances expansionary fiscal policy can make a real difference: see, for example, the experience of countries like ours during World War Two. A shared enemy, a fight for survival, and a willingness to subsume differences for a time makes a great deal of difference – even if, in many respects, it comes at longer term costs.

But unlike Mitchell, I still think monetary policy is, and should be, better placed to do the cyclical stabilisation role. That makes it vital that policymakers finally take steps to deal with the near-zero lower bound soon, or we will be left in the next recession with (a) no real options but fiscal policy, and (b) lots of real world constraints on the use of fiscal policy. Like Mitchell, I think involuntary unemployment (or underemployment for that matter) is something that gets too little attention – commands too little empathy – from those holding the commanding heights of our system. But I suspect that some mix of a more aggressive use of monetary policy, and welfare and labour market reforms that make it easier for people to get into work in the private economy, are the rather better way to start tackling the issue. How we can, or why we would, be content with one in twenty of our fellow citizens being unable to get work, despite actively looking – or why we are relaxed that so many more, not meeting those narrow definitions, can’t get the volume of work they’d like – is beyond me. Work is the path to a whole bunch of better family and social outcomes – one reason I’m so opposed to UBI schemes – and against that backdrop the indifference to the plight of the unemployed (or underemployed), largely across the political spectrum, is pretty deeply troubling.

But, whatever the rightness of his passion, I’m pretty sure Mitchell’s prescription isn’t the answer.

I don’t think advocates of MMT really help their cause by using the label Modern Monetary Theory. I understand the desire to make the point – pushing back against those too ready to invoke “but the market will never buy it” argument – that countries issuing their own currency never need to default. As a technical matter they don’t. Politically, some still choose to do so, and even if they never do there are very real (if not readily observable) limits well short of default, where the costs and risks no longer make any benefits worthwhile. Only failed states actually lapse into hyperinflation.

But in substance, MMT isn’t primarily about monetary policy at all, and as I noted at the start of the earlier post.

He is a proponent of something calling itself Modern Monetary Theory, but which is perhaps better thought of as old-school fiscal practice, with rhetoric and work schemes thrown into the mix.

One can mount a case for a more active use of macro policy to counter unemployment running above inevitable frictional/structural minima (I’ve made itself for several years), one can also mount a case for a more joined-up approach to fiscal and monetary policy (I’m not persuaded by the case, but it was standard practice in much of the OECD for several decades), and any politicians who doesn’t have a burning passion about minimising involuntary unemployment isn’t really worthy of the office. At present, in much of the world, that should be driving officials and politicians to (at very least) be better preparing to handle the next serious recession, in particular by doing something (there are various options) about the binding nature of the effective lower bound on nominal interest rates. It might not be a cause that resonates in Democratic primary debates, but it could make a real difference to the prospects of many ordinary people caught up through no fault of their own when the next serious downturn happens. Whatever one believes about the possibilities of fiscal policy – and I tend towards the sceptical end in most circumstances – you’d want to have as much help from monetary policy as one could get.

Perhaps next time, those who write the IGM questions could consider something a bit more nuanced, that might shed some light on the areas where there are real divergences of view around the light that economic theory and analysis can shed on such issues.

UPDATE: A post here, by a senior researcher at one of the regional Federal Reserve banks, also responds to this particular IGM survey.

Nice contribution to the changing face of macro regarding an increased focus on the use of ‘real’ resources (eg. potential labour). There is a ‘descriptive’ element to MMT that you point out (ie. A sovereign currency issuing govt can never become insolvent if they issue debt in their own currency and having a floating exchange rate) and also other descriptions; such as sovereign currency issuing govt’s have to spend ‘before’ they can tax; the govt sectors fiscal surplus equals the non-govt sectors fiscal deficit to the cent in national accounting that then requires private sector borrowing to fund spending, etc. Then there is the ‘prescriptive’ element arguing for a Job Guarantee, the dissolution of the EMU, the green new deal etc.

A rich MMT literature extends through economics from Knapp and Mitchell-Innes in the early 1900’s, through Keynes, Godley, Minsky, assembled as MMT by Wray, Mitchell, Kelton, Fulwiller and Mosler in the 1990’s where the descriptive part of macro becomes more prescriptive. I recommend reading the academic literature on MMT rather than the business journalist interpretations that descend into the money printing=hyperinflation fallacy. For example, a quick analysis of Zimbabwe reveals that it destroyed its economy by taking farms and giving them to freedom fighters, destroying their productive capacity, then borrowed in US dollars and then were forced to print money to service the debt, note: money printing comes at the end, not the start.

People with thoughtful comments like yours would be enhanced by engaging with the above literature.

LikeLike

Any government can decide to print money but it is the market that decides whether that money is worth anything at all. The term banana republic is usually used when you want to buy bread and have to show up with a wheel barrow full of cash.

LikeLike

On the contrary, I think Fiat money is given value by the involuntary obligation for the private sector to return the governments money back to it in the form of tax, to be destroyed (ie. it leaves the money supply). Further, the governments central bank determines value by setting the interest rate. I agree that the market has a role in determining the value of real things denominated in money. At least I think this is what the literature noted above says.

LikeLike

How about Venezuela?

Inflation rate in 2014 reached 69%. The rate then increased to 181% in 2015, 800% in 2016, 4,000% in 2017 and 2,295,981% in February 2019.

Does not sound like the government can actually control the value of money whether by printing or raising interest rates or taxing.

LikeLike

The value of currency has to be determined by the market as money these days are not actually limited or controlled by Central banks. It exists on a computer screen and is traded. The NZD is the 11th most highly traded currency in the world. Around a billion NZD is traded everyday by traders. But our exporters only require around $60 billion a year which is our total exports in its entirety. However, our annual NZD trading is around $300 billion a year.

Also we do not manufacture. Most of our day to day requirements are imported which requires us to sell NZD in order to buy imported goods. In order for us to sell NZD, someone with foreign currency must accept NZD.

LikeLike

Correction; Export Revenue is now $82 billion a year.

LikeLike

The RBNZ is the monopoly issuer of the NZD. If foreign entities want it then their options are to buy it, borrow it or accrue it, by as you say, sending us imports of things we can’t/won’t produce ourselves (Like the US does with China). Commercial banks create credit money by, again as you say, using a computer to mark up a borrowers account in the form of loans (an asset) but this is offset by a corresponding deposit (a liability) which means no new net financial assets are created. Leading us back again to the RBNZ being monopoly issuer, the only entity that can create new NZD denominated financial assets. Good discussion, thanks

LikeLike

Good question, same as Zimbabwe. The govt appropriated the productive capacity (oil – then ruined it), borrowed in a currency other than their own (Dollars and Cryptocurrency – then stole it) and had to print more to service the debt. The key is for a govt to spend money creating more real stuff, don’t compete with the private sector for resources when they full employment, issue your own currency and don’t borrow in one you don’t control.

LikeLike

The value of the NZD is underpinned by what you can buy with the NZD. The Labour/Greens/NZFirst governments move towards banning oil and gas exploration which is mostly of a export premium quality and a foreign buyers ban on property does make the NZD more of a high risk currency as it removes assets that are sought after by foreign currency holders that would have to buy NZD in order to buy our oil and gas or invest in exploration or invest in property.

Removing a trillion dollar asset with a foreign buyers ban removes quite a substantial asset that underpins the substance of the value of the NZD.

LikeLike

Even as someone who takes an arguably even more extreme heterodox position (I want full reserve banking) I find MMT to be bizarre and difficult to comprehend and its advocates seem very keen to make their arguments as obscure as possible.

It just seems to me like it is fiscal policy (i.e. politics) trying to wrap itself up in the guise of monetary policy.

LikeLike

“Deficits DO matter because of their real effects.”

“Governments can’t run deficits with no regard to inflationary consequences.”

Can we establish that this is the basic MMT position?. Not something else.

Thank you Mr Redell for pointing out the straw men that keep getting trotted out. I appreciate that.

MMT says the power of the public purse that a fiat currency allows should be used to stabilise the economy to maintain full employment. I believe monetary policy clearly isn’t enough or its results are unclear and indirect. An empirical look at the outcome of last 10 years can’t claim that it is effective enough.

My question is, if sensible ongoing fiscal deficits increase demand, growth, employment etc and don’t cause damaging inflation or “default” – where is the problem exactly? Japan clearly demonstrates this.

MMT as espoused by its serious academic proponents – Mitchell, Mosler, Kelton, Wray, Fullweiller – never says that governments are not constrained by real resources and real capacity and can print money willy-nilly.

Negative rates and getting rid of cash to allow that doesn’t convince me. In a world of negative rates and employment insecurity I will save more of my income in a downturn. It seems like more desperate string pushing to me. Getting rid of cash to enable the negative rates or charging for cash to me seems far more politically infeasible to me than a Job Guarantee that employs people when the private sector won’t. NGDP targeting that the Mercatus people want seems to be up against the same problem – lowering interest rates just isn’t that effective. If it were, surely we’d all be in hyper boom by now?

An MMT style job guarantee kicks in when necessary immediately without a need for politicians to debate the spending. It gets money to the people who will spend it by ensuring a basic living wage. It sustains demand immediately in a way that a few dollars of your mortgage does not. It is a potentially fantastic automatic stabiliser because unlike the Dole it keeps people active and employable and avoids them becoming a risk for employers later. It is better than prime pumping “military keynesianism” cause it hires off the bottom to those that most need it rather than potentially inflating sectors already doing okay.

MMT might scare people who dislike an activist state in the economy. But surely conservatives prefer people to work than lounge on Dole or UBI for a living? And tax cuts could be used rather than public spending projects to generate the necessary demand if that is the political preference.

I live in a party of NZ were clearly there are a lot of people for whom years of under-employment and precarious employment over two generations since the 80s has not been a positive force in their lives. They are now unemployable such is their state of mental and physical health. Cutting their basic benefits will just push them into begging and homelessness. If they’d had a job guarantee programme to slot into I would wager the outcomes would have been far better.The Job Guarantee – as opposed to the NAIRU – is a much more ethical humane way to discipline inflation. I am a Leftist, but I believe we have a duty to contribute to society in order to receive a living. Not something for nothing.

LikeLike