There was a strange editorial in the Listener this week, lamenting what they see as New Zealanders’ mania for consumption spending. The editorial starts from the fact that the proportion of New Zealanders reaching age 65 mortgage-free has been in decline, and goes off half-cocked from there. There is no mention at all, for example, of the other important fact that New Zealand real house prices have risen very sharply and are now, relative to incomes, some of the most expensive in the world. You would expect that would change the distribution of indebtedness and make it more likely that more old people would still have debt (as well as an artificially more valuable, not very liquid, asset).

But whoever wrote the editorial is convinced that the problem is consumption.

“We’ve felt freer to upgrade the car, have a holiday or renovate using debt rather than savings”

“Loans have seemed so affordable, and consumer goods so increasingly accessible, that the “on-the-house” habit has done further damage to the economy. It has three highly undesirable featires: low to stalled productivity, very low income growth and consumptive spending bounding ahead.”

“…a more deep-seated problem than our failure to tax capital gains. It’s about how we’re spending – and perhaps more importanyly, why we’re spending. The internet has made every product imaginable deliverable to our doors – amped up by such marketing constructs as Black Friday – and ambient anxiety-fuelling over “not missing out” at Easter, Christmas, Halloween and the like have stoked our spending to ever higher records.”

and so on.

But it is, pretty much, a fact-free zone.

It shouldn’t be surprising that (real) spending is higher than it used to be and that people are buying more stuff. We have higher incomes than we used to have. Yes, I bang on more than most about the failure of policy here and weak productivity growth, but real per capita GDP is now about 90 per cent higher than it was in 1970. All else equal, one might expect the typical New Zealander to be consuming a lot more stuff (goods and services) – they can afford to.

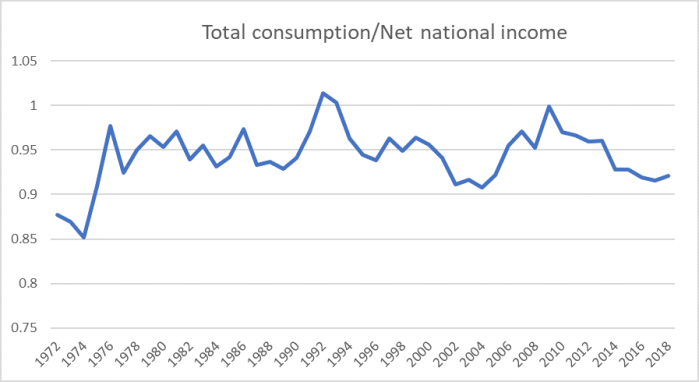

And how has consumption spending tracked relative to income? This chart shows all consumption (public and private) as a share of net national income. Net national income is the measure of how much income residents of New Zealand have available to spend: relative to GDP, it subtracts the bit of New Zealand production that actually accrues to foreigners (well, non-residents), and also subtracts an allowance for depreciation (some of gross earnings needs to be spent on just maintaining/replacing the capital stock that helps generate the income). To believe the Listener story, the line should be trending upwards, perhaps especially since the financial system was liberalised in the mid 1980s.

It doesn’t of course. The trend has been dead-flat for decades now. There is some cyclical variability – those last two peaks were the years of serious recessions (March years 1992 and 2009) – since consumption spending tends to be more stable than national income. Fiscal policy makes a difference too: when governments are running big surpluses (as in the early 00s) the consumption share of income tends to be temporarily subdued. On the other hand, there is no sign that, in aggregate, financial liberalisation made any material difference. Markedly higher house prices haven’t either – which shouldn’t really be surprising, as for every person who feels a bit wealthier, there is another for whom home purchase is that much further off.

And there just is no story, able to be defended from the data, about New Zealanders in aggregate on a consumption splurge. Sure our savings rates are modest by international standards, but they’ve been so for a long long time. And, to repeat, consumption is consistently less than income (see chart). Mr Micawber would approve

“Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen [pounds] nineteen [shillings] and six [pence], result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds ought and six, result misery.”

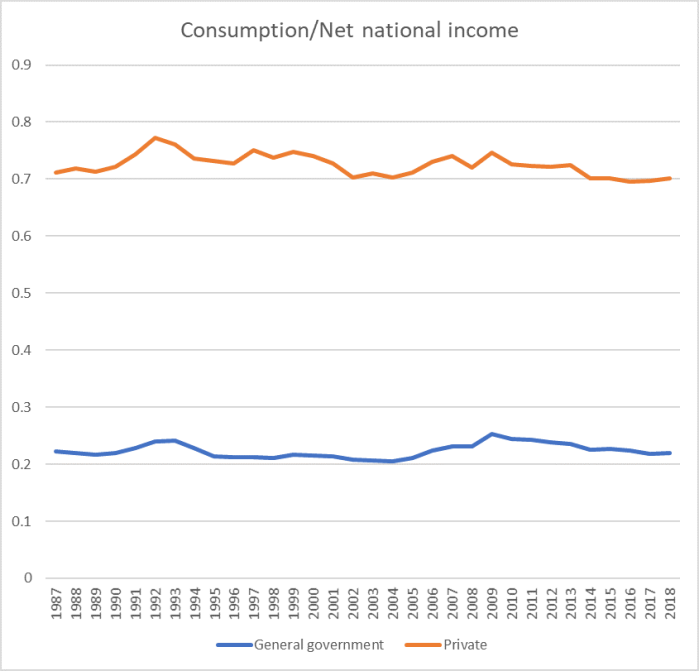

That long-term chart used total consumption (public and private). For many purposes that is the right metric to use: there is a considerable degree of substitutability between government consumption and private consumption. (And if, for example, the government gave you a voucher to pay for your kids’ schooling redeemable only at the local state school, the resulting education services would probably be measured as private consumption rather than – as at present – government consumption. Nothing of substance would have changed, just the labelling).

But there is a breakdown between public and private consumption going back as far as 1987. Here is that chart, with the components again shown as shares of net national income (March year annual data).

No trend (beyond “almost dead flat”). For what little it is worth, in the most recent year both public and private consumption spending were a touch below the respective 30 year averages.

The sad truth is that actual consumption in New Zealand is probably quite a bit lower than it should be. Back in 1970, real GDP per capita in New Zealand was about the same as that in Germany. These days, average GDP per capita in Germany is about 30 per cent higher than that in New Zealand (and hourly productivity is about 60 per cent higher). The Germans not only get to consume more stuff but (in economist-speak) to consume more leisure (hours worked per capita are much higher in New Zealand than in Germany). If we’d managed to match German economic performance, almost certainly the typical New Zealand household would be consuming more, not less. Quite possibly our average savings rate might be a bit higher too.

I’m a Puritan by upbringing and inclination and so when I read lines like this from the Listener editorial

“Popular TV home-renovation contests and “property porn” create a chronic sense of FOMO, with faddy edicts: one must refit one’s kitchen and bathroom every five years; last year’s wallpaper is now dated.”

I can nod along (even while wondering just how many people actually behave that way). Being Puritan by background, middle-aged, and male, the idea of “fast fashion” just seems weird. “Black Friday” is an alien import, and I buy books from (among other places) charity shops (rather than providing them – as the editorial puts it – with “unsaleable dumpings from nouveau declutterers”). But odd as some of these phenomena might be, they really don’t seem to add up to much in the aggregate consumption data.

There are big problems around the housing market, almost entirely the result of central and local government choices. We should worry – as the Listener does – about the growing share of people carrying debt into old-age, or never having been able to buy a house in the first place. But the issues have very little to do with some wholly-mythical national consumption splurge. And responsibility needs to be sheeted home to central and local governments, not to consumers trying to make the best of their, increasingly constrained, options.

It could be argued that the masses have been tacitly encouraged to spend more because to the incredibly low interest rates in most countries resulting in an exceptionally low cost of capital when making spending decisions. The same situation has also created a disincentive to save. This logic extends to property investment. The low interest rates have pushed people into real estate and the Politicians on both side of the House have been very happy to let this continue for at least the last 20 years on the basis it often gets them re-elected. While the politicians are complicit the RBNZ is responsible for monetary management. I will concede that they are just following other Central Banks approach to monetary management. Perhaps it is time for the boffins to find some new textbooks or pick up some very old ones. To blame consumers for the present situation misses all of the above and is only a distraction from bigger structural issues.

LikeLike

Personally I don’t think we are buying less stuff. It is just that all the stuff we buy are now a lot cheaper. China and the emerging countries like Vietnam and India are producing from mega massive factories to supply the world with cheaper and cheaper consumables.

Personally my forever resolution to myself in the 2008/2009 recession that if I survive that recession, I have learnt my lesson well,

Lesson 1: that the RBNZ and RB Governors are nutcases and will intentionally damage the NZ economy and obliterate NZ industries wholesale to keep inflation lower than 3%.

Lesson 2: spend your wealth outside of NZ to dampen inflation in NZ

LikeLike

“real per capita GDP is now about 90 per cent higher than it was in 1970” . That sounds good but would you explain that in terms of your overall thesis: productivity; the exchange rate and adding people?

LikeLike

Just v quickly for now….. most other advanced countries have done materially better. We are richer than we were, but growing slowly have drifted behind other advanced countries.

LikeLike

I’m just reading this

Click to access mi-jarrett-comm.pdf

LikeLike

The very first public telling of an early version of my story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Would’ve fooled me

There are more Maserarti’s and Ferrari’s and Lamborghini’s running around Auckland today (in the hands of princelings) than there were 50 years ago – almost unheard of then – now a dime-a-dozen

Maybe they don’t have them in Wellington

LikeLike

A) in aggregate we are richer, and

B) there are also more troubled and eg homeless people

LikeLiked by 1 person

In Queenstown they depend on tourism. Real wages have been falling in tourism and hospitality (according to a tourism lecturer on RNZ); rents are astronomical. They can’t afford infrastructure without taxpayer help. In 2004 The Boston Globe travel writer opined “if this is your idea of a holiday then so be it, other wise it serves only as a warning to the perils of overdevelopment”. I walked down Mt Roy with a retired USGS geologist in about 2000 he said “you are ruining this country” and he and his wife had been looking all over for something more to their taste – they chose Tasmania. Those hardened to city life (Taiwanese) seem to find it to their liking.

There are 5 different property markets so bolt-holes for the rich.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Queenstown development meme is “this is where Aspen was at in…..”

LikeLike

The difference is in the language – “in aggregate” covers a lot of ground

On a micro basis there are probably a lot more (imported rich) that outweigh the number of troubled and homeless people – both numerically and money-wise – thus we are richer in aggregate

LikeLike

…. and I’m not sure I enjoy the “we are richer”

Some are – some are not

LikeLike

If you want to know the meaning of poverty and homeless, take a holiday into central Los Angeles. Night time is like a visit to Spookers horror show. with rats scurrying around uncollected rubbish.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think people accept an economic hierarchy depending on the rules: you make a movie, write a book, start a company, develop software……. but the property market is different.

LikeLike

Most of may friends and family think the property market is different and I have given up trying to convince otherwise. I still remember in 1985/86 I had an ANZ Mortgage with an interest rate of 22%. As I remember no one thought that was a problem because there was no choice and the property market was surprisingly healthy at the time. Needless to say everything changed in October 1987. Things are only a given until there is a new reality.

LikeLiked by 2 people

The property market does require 3 main things to dive prices. Limited supply, increasing demand and leverage.

LikeLike

Or drive prices.

LikeLike