A week or two back I foreshadowed a forthcoming paper by my former colleague Ian Harrison reviewing the Reserve Bank’s proposals under which the banks would have to greatly increase the volume of capital simply to carry on doing the business they are doing now.

Like me, Ian spent decades at the Reserve Bank. But much of his time was spent specifically in the area of banking regulation and bank supervision, including leading much of the modelling work done a few years ago as part of the Basle III process, which resulted in something like the current bank capital requirements. He knows the detail in this area, has consulted on this sort of stuff since leaving the Bank, and has invested a great deal of time and effort over the last couple of months in getting to grips with the Bank’s proposals, reviewing the various papers they’ve published, and going back and reviewing the papers the Bank has cited in support of their case. The result is his (50 page) review document. Here are his key conclusions (overlapping in various places with points I’ve made in post here). Ian does not pull his punches.

Part two: Key conclusions

1. The ‘risk tolerance’ approach is a backward step that ignores a consideration of both the costs and benefits of the policy. The soundness test is based on an arbitrarily chosen probability of bank failure that ignores the cost of meeting the target. The Bank has ignored its own cost benefit model which did take the probability of bank failure, the costs of a failure, the interest rate costs of higher capital and societal risk aversion into account.

2. Bank decision based on fabricated evidence. The Banks’s decision to pursue a 1:200 failure target was purportedly based on evidence from a version of the Basel advanced model. It was manipulated to produce the right answer. Initially, a 1:100 target was proposed, but when this couldn’t generate a capital increase, the target was switched to 1:200 at the last minute.

The Bank’s model inputs were not credible. It was assumed that all loans were higher risk business loans and that the probability of loan default, a key model input, was more than two and a half times the estimates the Reserve Bank has approved banks to use in their capital modelling.

The Bank’s analysis was embarrassingly bad, so it attempted to cover this up with a subsequent information paper that was written after the decision was made, and after the Consultation paper was released. It reached the same conclusion on the required level of capital, but only by assuming a 1:333 failure probability, and by using model inputs that were still not credible.

3. A 1:200 target can be met with a capital ratio of around 8 percent. If the Basel model were rerun using credible inputs if would probably show that a 1:200 failure rate can be met with a capital ratio of around 8 percent.

4. The policy will be costly. The Bank has down played the interest rate impact of the policy, saying any increases will be ‘minimal’. Based on its own assessment of the interest rate impact, the annual cost will be about $1.5-2 billion a year. The present value of the cost of the policy could be in excess of $30 billion.

A homeowner with a $400,000 mortgage could be paying an additional $1,000 a year. A business with a $5 million loan could be paying an additional $50,000.

5. The Bank’s assessment that the banking system is currently unsound is at odds with rating agency assessments and borders on the irresponsible. The rating agancies’ assessment of the four major banks is AA-, suggesting a failure rate of 1:1250. The Bank is now saying that, at current capital ratios, the banking system is ‘unsound’ because the failure rate is worse than 1:200. Or in other words the New Zealand banking system is not too far from ‘junk’ status. The international evidence does not support the Bank’s contention that the probability of a crisis is worse than 1:200. The Bank has ignored the fact that banks will need to hold an operating margin over the regulatory minimum, and has not adjusted New Zealand capital ratios to international standards to make a fair like-for-like comparison.

6. The Bank‘s analysis ignores the fact that the banking system is mostly foreign owned. Foreign ownership increases the cost of higher capital because the borrowing cost increases flow to foreign owners. Foreign owners will support their subsidiaries in certain circumstances, which reduces the probability of a bank failure. There is little point in having a higher CET1 ratio than Australia, because if a parent fails then it is highly likely that the subsidiary will also fail, because of the contagion effect. A New Zealand subsidiary might still appear to have plenty capital, but depositors will run and the Reserve Bank and government will have to intervene.

7. The Australian option of increasing tier two capital has been ignored. APRA is proposing to increase bank capital by five percentage points, but will allow banks to use tier two capital to meet the higher target. This provides the same benefits, in a crisis, as CET1 capital, but at about one fifth of the cost. New Zealanders will be required to spend an additional $1.2 billion a year in interest costs for almost no benefit in terms of more resilience to a severe crisis.

8. The benefits of higher capital are modest. Most of the costs of a banking failure are due to borrowing decisions made before the downturn. This will impose costs regardless of the amount of capital held. With current levels of bank capital failures will be rare, with the main cost likely to be a government capital injection. The experience with most banking crises, in countries most like New Zealand, is that governments have recovered most of their costs when the bank shares are subsequently sold.

9. The Bank is mis-selling insurance. The Bank is selling a form of insurance to the New Zealand public, but it vague about the premium costs and has exaggerated the benefits. The premium is the $1.5-2 billion. The benefit would be around a 10 percent reduction in the economic cost of a financial crisis, with an expected return of a few tens of millions.

An informed, rational public would not buy this policy.

10. New Zealand banks already well capitalised compared to international norms. A recent PricewaterhouseCoopers report argued that if New Zealand bank capital ratios were calculated using international measurement standards they would be 6 percentage points higher, placing New Zealand in the upper ranks of well capitalised banking systems. The Reserve Bank critised some details in the report, but has not produced is own assessment as Australia’s APRA has done.

11. The Bank has forgotten about the OBR. The Open Bank Resolution (OBR) bank failure mechanism, was originally conceived as a substitute for higher capital to reduce fiscal risk, and to reduce the costs of a bank failure. While banks are been required to spend almost $1 billion on outsourcing policies to supportthe OBR, it does not appear in the capital review at all – despite the Governor’s arguments that the main justification for capital increases is to reduce fiscal risk.

The bottom line?

An informed, rational public would not buy this policy.

But, as it happens, an informed rational public won’t get a say. The Governor proposes and (under New Zealand law) disposes: prosecutor, judge, jury, and appellate court in his own case.

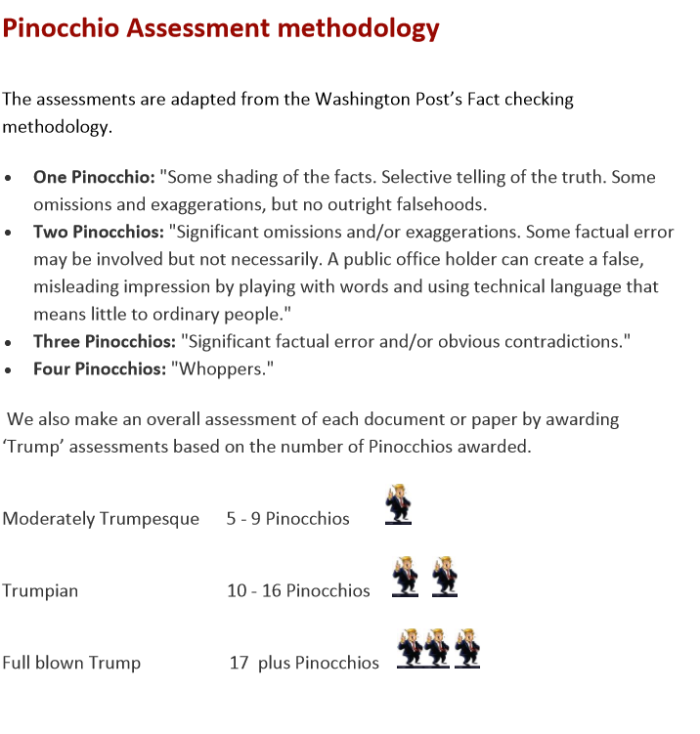

Partly, I gather, for his own amusement, and partly to help respond accessibly to some specific assertions/arguments in the more accessible material the Bank has put out to support the Governor’s case, Ian has a separate document, the Pinocchio awards.

The Governor is a great deal smarter and more analytically capable than Donald Trump, but on Ian’s reading, he is resorting to the financial regulator’s equivalent of questionable Trumpian rhetoric to champion the indefensible. Against Trump there are the courts and Congress. Against a Governor with a whim and the bit between his teeth……well, nothing really.

It would be interesting to see what the Reserve Bank makes of Ian’s arguments and evidence.

UPDATE: A fairly accessible summary of some of Ian Harrison’s key argument in this article by veteran journalist Jenny Ruth.

Reblogged this on Utopia – you are standing in it!.

LikeLike

Michael

As the negatives largely boil down to the banks having a higher cost of capital and needing to widen their loan margins (I think there is pretty good evidence that the large NZ banks are efficient so will struggle to reduce costs), can you explain this quote “A homeowner with a $400,000 mortgage could be paying an additional $1,000 a year. A business with a $5 million loan could be paying an additional $50,000”.

The macro point seems to be than on $500 billion of assets, spreads will have to widen by about $2 billion, ie. 0.4%. why in the excerpt is the householder paying 0.25%pa. more but the company 1.0%pa. Is this explained by risk-weighting?

Thanks

Tim

LikeLike

Given that banks are still flush with Savers deposits which they have to lend out and now faced with the higher Capital requirement does mean an additional injection of cash which also needs to be on lent in order to generate a return. It does point to a downward pressure on lending interest rates. Wonder when the banks start to panic as profitability gets eroded in the face of a drop in the lending demand as a perfect storm?

LikeLike

HSBC has launched a two-year special rate of 3.69 per cent, the lowest-ever fixed home loan rate from any bank.

The special rate is also the lowest rate that HSBC has ever offered in the New Zealand market, trumping its previous lowest rate of 3.79 per cent for a 2-year term in August 2016, which at the time was the lowest fixed home loan rate offered in the New Zealand market for over 50 years.

LikeLike

There is no net injection of cash. One would, presumably, expect banks to replace some of their offshore wholesale funding, and maybe bid a little less aggressively for term deposits as well (the impact of the higher capital requirements will be split between higher lending rates and low deposit rates – in each case, mostly for retail and SME customers).

LikeLike

Bid less aggressively for term deposits equates to a downward pressure on deposit interest rates. But unfortunately it does not necessarily equate to less savers deposits available. Part of the reason is kiwisaver. Most kiwisaver schemes are mostly default conservative or balanced schemes which equates to upwards of 40% of the investments in term deposits which is incremental each and every month due to employer and employee contributions.

The other reason is cashed up baby boomers after selling up their Auckland mansions and either moving out to the regions or into rest homes in increasing numbers. With the various sharemarkets around the world in wild gyrations, term deposits still generate a better return than gold that has no income component.

And of course migrants having cashed up their overseas homes and starting up new lives with more cash available in cheaper NZ housing or with younger migrants, with overseas parents that want to take advantage of our Approved Issuer levy scheme at zero tax deductions on interest earned.

LikeLike

Also Kiwisaver earnings have a compound effect ie it is automatically reinvested, which also accelerates the amounts that must be invested in Term deposits.

LikeLike

Good question. I don’t know the answer, but have asked Ian.

LikeLike

The quoted parts of the analysis don’t note the $250,000 deposit insurance scheme available in Australia.

It would seem sensible to:

a) implement the same $250,000 deposit insurance in NZ

b) set the capital requirements in NZ the same as Australia

Then the RBNZ undertake a proper business case study to determine whether this can be improved upon.

LikeLike

quote – “While banks are been required to spend almost $1 billion on outsourcing policies to support the OBR”

Clarification

Does that mean the banks have spent almost $1 billion, or

Would be required to spend $1 billion supporting OBR

LikeLike

It wil be a description of what has already been spent (prob some mix of capital cost and the capitalised value of higher operating costs). There has been expenditure on both domestic systems modification – to enable OBR to be implemented pretty much on demand – but even more so around the outsourcing requirements (required to ensure that the NZ subsidiaries can operate on a standalone basis, in the event the NZ sub fails and OBR is invoked). One can argue that the outsourcing provisions are not just about OBR, but they are almost totally unncessary if one assumes – as seems highly likely – that any serious problem in the Aus banking groups will be sorted out on a trans-Tasman political level. Upon resolution, the services being provided to the NZ banks by the parents would then presumably continue to be provided as normal.

LikeLike

I thought the OBR was more a reminder, ie the reference to a resolution, to banks that the RBNZ has the authority under banks licencing to be able to step in and suspend all bank operations and to initiate whatever steps to reinstate a banks solvency position including a Greek haircut on savers deposits if required.

Not sure if the OBR includes the option of the RBNZ taking control of the share ownership and providing the government with the option of recapitalising the insolvent bank as they did with Air NZ through a share buyback when Air NZ was on the brink of a receivership and share value was in the cents.

LikeLike

Thirty billion here, thirty billion also lost through the offshore oil and gas exploration ban. That’s 60 billion lost so far and we’re only halfway through the Coalition’s term.

LikeLike

Add in another $3 billion provincial fund squandered to buy Winston Peters MaoriFirst party votes and the billion dollar tree mulching program of an incompetent Shane Jones

LikeLike