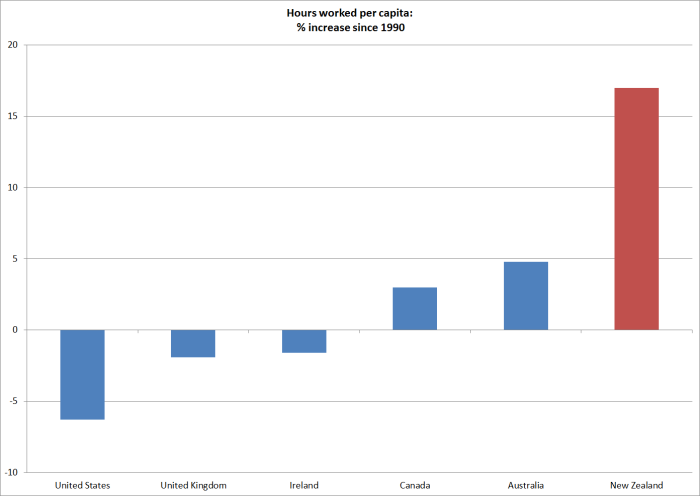

The other day, for some reason, I was looking back at the records of this blog, and got curious about which posts had had the most specific views. It turned out that for some reason (I think it got linked to overseas) this early post – about how New Zealand’s economy had done relative to other advanced countries since 2007 – was the “winner”. Rereading the post, I lit upon this chart

As I noted then

Hours worked are an input (which comes at a cost) not an output, so higher hours worked aren’t automatically a good thing. There are good dimensions to it, if (for example) people are coming off long-term welfare back into the workforce, or older people are keen and able to stay in the workforce. Hours worked per capita also gets affected by different demographic patterns – they will be lower in countries with lots of under-15s or over 70s. But, equally, part of the story of New Zealand in the last 25 years is that we have managed to limit the deterioration in our GDP per capita, relative to that in other countries, by working more. Productivity would be better.

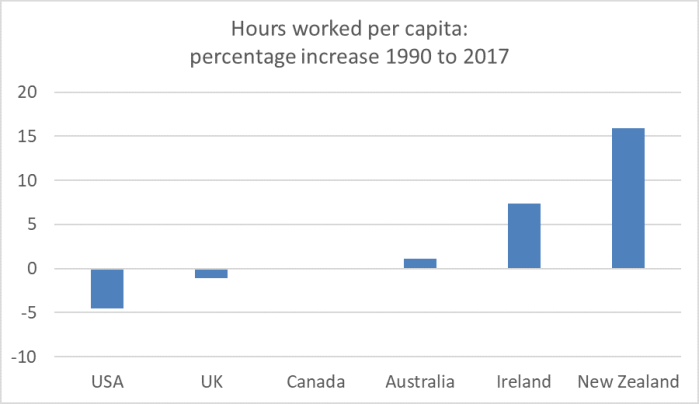

Over the full period since 1990, here is the change in hours worked per capita for New Zealand and the other Anglo countries, countries with reasonably similar demographics to our own.

1990 was the year just prior to a recession in many countries, including New Zealand, and is a not uncommon jumping-off date for looking at the experience of New Zealand since the reform era.

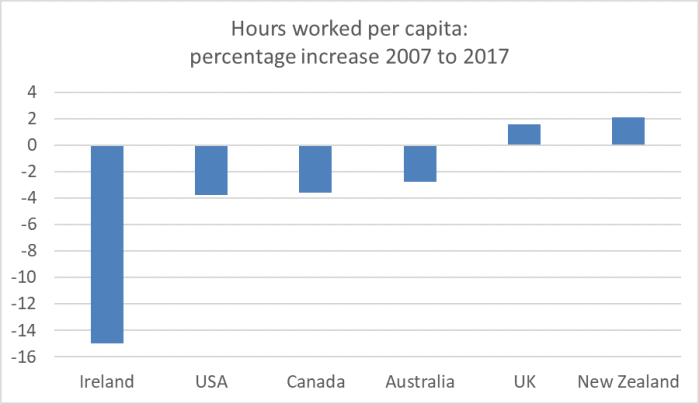

Since the post was almost four years old, I was curious whether anything much had changed. Here is the same chart, using data from the Total Economy Database maintained by the Conference Board.

Something of a recovery in Ireland, but otherwise not much. The difference between New Zealand and the other countries in the chart isn’t mainly a cyclical story, but even in the last decade a larger proportion of New Zealand’s per capita GDP growth has come from working more hours (per capita).

(Interestingly, the UK labour productivity growth record over that decade has been even worse than that of New Zealand.)

I had a quick look at a wider group of advanced economies (OECD + EU + Singapore and Taiwan). For the full period since 1990 there isn’t complete data for all countries (gaps mostly the former Communist countries of central and eastern Europe), but of the 32 countries for which there is data, hours worked per capita dropped by 1 per cent for the median country (up 16 per cent in New Zealand). For the more recent period, where there is full data, the median country spent 2 per cent fewer hours per capita working, while in New Zealand median hours per capita increased by 2 per cent.

(For those interested, there is a group of countries (Singapore, Hungary, Israel, Chile, Mexico, Poland) where hours per capita have increased materially more than in New Zealand over the last decade.)

I am not trying to draw any particular policy conclusions from these numbers, just to highlight them. And it is not as if New Zealanders had been leisured people at the start of the period and were only now getting back to advanced country norms. In fact, by 2017 we had among the highest hours worked per capita of any of the 40+ countries in my sample (Singapore is off-the-charts high, and South Korea comes second).

As a reminder, hours worked are an input not an output. High (or increasing) hours worked is generally not some achievement to be celebrated, although there can be some caveats to that.

If the unemployment rate had been particularly high at the start of the period, one might genuinely welcome it dropping. Involuntary unemployment is, almost by defintion, a bad thing. But when my comparisons started (in 1990) New Zealand’s unemployment rate was about the middle of the pack for the Anglo countries in the charts (by 2007 we had the lowest unemployment rate of any of them).

If you are uneasy that the welfare system accommodates too many people not working who should be providing for themselves, then successful welfare reforms might increase average hours worked per capita and that might then be regarded as a good thing – whether fiscally, socially or whatever. The proportion of working age adults on welfare benefits (ie including the unemployed) did drop quite bit in the 1990s and early 2000s. But it was 10 per cent in 2007 and it was still 10 per cent in 2018.

Tax system provisions (or the interaction with pension rules) can also deter people from working when they might otherwise choose to. New Zealand has a public pension system that specifically does not deter people from staying in the workforce after age 65 if they so prefer, and between 1990 and 2007 we increased the NZS eligibility age by a whole five years. Personally, I think that was a desirable change, but the fact remains that high and rising hours worked per capita has not been a complement to some stellar productivity performance and improving opportunities.

In aggregate, more New Zealanders have been working more hours to – in effect – offset some of the relative income loss that our disappointing productivity performance would otherwise have led to. As a country, our tenuous grip on upper-income status (really not much more than upper middle-income these days) is sustained only by working ever harder. That might be, in some sense, an appropriate second-best (for the individuals making those choices, reluctantly or otherwise). It is not obviously any sort of first-best outcome.

Can you clarify: is the hours worked per capita just the total reported hours worked divided by the current estimated population of the country?

If that is right then there are so many factors that would move the number: changing fraction of the population who are children, changing number studying (or does that count as work?), changes to maternity leave, changes to life expectancy, inaccurate values for total hours worked – for the self-employed working from home there are tax reasons for claiming to work either more or less than 20 hours (I forget which) and when I was a self employed computer programmer it was very dificult to estimate when I was working and when I was not – especially when making and drinking coffee.

It needs more analysis to make sense. For example do young graduates with large student loans work longer than I did at the same age without any debt? Do singles work more than those in relationships? Do foreign owned companies expect longer hours?

LikeLike

Yes, it is simply total hours worked/population. And, yes, lots of things – regulatory, tax, and social, age structure etc – will influence the numbers (partly why I focused on a group of countries with some cultural affinities and moderately similar demographics).

LikeLike

Hours worked per capita percentage increase can be misleading

For example assume

in 1990 US absolute hours worked per capita = 40

in 1990 NZ absolute hours worked per capita = 30

Both countries increase the absolute hours worked by 10 hours

US increase % = 25%

NZ increase % = 33%

Boom – extreme example – but you get the drift

LikeLike

I agree, values rather than percentages. I would tackle this as a spreadsheet with three groups: Young (say under 20) excluding and including those in permanent education; Adult (excluding those in permanent education) and Elderly (say over 65) – for each of these the hours worked in 1990 and the hours worked now. Percentages are not showing work, they are merely showing that things have changed.

The first graph tells us one thing only – something odd has happened in NZ but whether the oddity was with the initial state or the final state is unclear.

My pure guess is the biggest factor will be NZ having increased the number of elderly people chosing to work.

Is this paid employment? I collected my grandson from school this week and he said ‘Mrs xxxxx must like teaching’; as asked why and he said ‘well she is retired but she comes and teaches us for nothing’. [I strongly suspect she is a deservedly well-paid relief teacher.]

LikeLiked by 1 person

All fine points, but the data (hours) are not available to the public to examine.

My main point was a very very simple one. if you think per capita incomes here haven’t done too badly since the reforms, that is largely because (as NZers as a whole) we’ve increased average hours worked a lot in comparison with the other culturally similar countries we often benchmark ourselves against. It is the flip side to my (oft-repeated) point about how mediocre our productivity growth performance has been over that time (from memory about 5th worst of all those countries).

A subsidiary implied point is that it is highly unlikely we will manage a similar faster growth in hours performance in the next 27 years (not even clear it would be desirable, labour being a cost to the supplier), so if we don’t do something about fixing productivity growth, the per capita incomes gaps are likely to widen more sharply than in the last 27.

LikeLike

I listened to a 81 year old condemn NZ for her poverty situation. Clearly a migrant from UK and she indicated that has worked and paid.her taxes for 50years but no one cares for her now. She lives in her car because Housing NZ and social welfare services can’t find her suitable accommodation. She was shown a guest house for $300 a nite which she has to pay for from her $250 a week super and whatever she can earn from part time work. She decided to go back to live in her car.

LikeLike

Not surprised ….

quote 1: “My main point was a very, very simple one. if you think per capita incomes here haven’t done too badly since the reforms …”

quote 2: “A subsidiary implied point is that it is highly unlikely we will manage a similar faster growth in hours performance in the next 27 years”

Two entries in my CV are a stint working for the NZ Herald and 10 years working for NZ News Ltd publisher of the Auckland Star. The editor in chief was Geoffrey Upton. He was a huge man ‘6’6″of huge stature. (198 centre-metres). He was a man of frequent sayings” one of which was aimed at novice reporters and columnists “you have the first paragraph to communicate what your article is about”. Your article should then substantiate what is contained in the first paragraph. The accompanying headline will reflect the first paragraph. The article should reflect the headline and the first paragraph – and nothing more

This article is overwhelmed by graphs and cross-country comparisons – they are confusing. Not sure what the take-away of the cross-country comparisons are. Will anything ever be done about them. Does Treasury or the Government do anything with them. Seems not.

Examine Bernard Hickey’s articles at Newsroom you will find he “sort of” follows that rule

Geoffrey Upton

http://www.stuff.co.nz/auckland/local-news/local-blogs/off-pat/6790514/War-hero-died-to-save-his-men

LikeLiked by 1 person

That sounds like practical advice to anyone charged with running the news pages of a newspaper……….

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, that is certainly a potential issue, although I had checked and determined that the charts didn’t look materially different whichever way one expressed the change. Starting from scratch I’d have use the actual change in hours (not % change), but I was comparing with the 2015 version which I’d done then in % changes.

LikeLike

Where is the incentive to invest in productivity enhancing technology and in up-skilling and training workers when there is pretty high underemployment and loads of people wanting more hours?

Clearly most of those working more hours need to work more hours otherwise they wouldn’t.

When that large pool is finally exhausted, then surely the pressure would be on to invest in enhancing productivity in competitive industries or face rising wage costs?

But what if demand is kept chronically too low to ever exhaust that pool?

LikeLike

Most of the productivity gains from computers, iPhones and pads are already in place. Very little more can be gained in our largest industries being the service sector. In the past we just added more cows as cows are not counted as working hours but economists forgot to factor in the massive resources in land, water and the pollution effects of peak cow.

Robots would have to get a lot better to impact the service sector productivity to any noticeable degree. Robots in any service sector is still abysmal, A $2 million robot still can’t turn a round handle, push open a door and step through which a 5 year old human can easily do blindfolded.

Watched a immobile service robot with extendable arms make cocktail drinks in Las Vegas during my Xmas holiday travel recently, orders and payments via iPad consoles at the table. The 20 tables were mostly empty with one waitress to assist 5 patrons. I joined and that made 6 people during a peak busy holiday evening. The problem was delivery. After the drinks were made by the robot no one was sure whose drink it was. Next door, a competition restaurant had 3 human bar tenders and 5 sexy human waitresses and it was full of drinking revellers.

LikeLike

The recent problem with fruit fly demonstrated how much free taxpayer subsidies goes into our Primary Industries. It will cost $1 million for each fruit fly which the industry will not be paying for. Farmers pay less than 5% of our tax revenue but expects the government to pay 100% of the biosecurity costs as well as pay for damages suffered by farmers for biosecurity lapses. Our farmers are a heavily government subsidised industry.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Michael, I think you’ve made the link yourself, but if labour is cheap there is no obvious incentive for employers to invest in labour-saving capital to improve labour, or total factor, productivity, even when finance is cheap.

Immigration by low skill (and casual) workers helps keep labour costs down – employers don’t have to pay higher wages, employ more skilled workers and use more complex systems or machinery, or shift to producing higher value added products and services.

Also, though NZ is a cheap and easy place to start a business, the ongoing compliance costs and liabilities (especially if employing people) can discourage young people from starting or running their own business. [I think surveys consistently show that 70% + of young people want to get a good job as a career, not start their own business].

So, restricting immigration to high-skilled (and high net worth) individuals should be a positive policy to address productivity. Higher wages for high-skilled people would also make NZ more attractive internationally for work and study here, creating a virtuous cycle, shifting us away from the idea that people come because they like the lifestyle and social welfare benefits.

In the 70’s (and occasionally since) there has been a view that NZ Inc should capitalize on its high level of education and become focused on a high value added economy [Porter’s clusters of excellence etc] – this fits with the ideal of a clean, green beautiful quality country that leads intellectually; is expensive to visit or move to; and not one designed to attract freedom campers and backpackers. A focus on added value and quality is not necessary elitist, though many clearly see it that way.

Instead it appears we have continued to rely on commodity (farming) exports, growth in tourist (of all kinds) numbers and high immigration of unskilled workers to do what entitled kiwis feel they don’t want to. Having to work longer, rather than smarter, to make ends meet hardly seems like a positive development direction.

A rich progressive country can afford a strong welfare “safety net”. An increasingly low (relative) per capital income country will struggle with that.

As always it starts with education. Giving everyone the opportunity to get a “certificate” so they can get a job should not be the main focus of the system. Universities are not training institutes. Higher education should be seeking to push the boundaries of knowledge; attract the world’s best (not just fee payers); and seed the wealth of the next generation.

I would be interested to read a blog from you on how NZ’s eduction system has changed since the post war 50’s?

LikeLiked by 3 people

Michael, this is a continuing theme in your blog, but I do not understand the underlying economics.

Trade theory says that we should specialise in products and services for which we have a comparative advantage. Since NZ is a small country as far away from the bright centre of the universe as it is possible to get, we do not (and will never) have a comparative advantage in making cars or electronics or ships or whatever for the world market. We do not have mineral resources of any important scale, although we do tend to waste the opportunities provided by the endowment that we have. Nobody in their right mind would try to turn NZ into a world centre for financial services or massive IT industries (Microsoft or Facebook) or branded consumer goods (Nestle, Proctor and Gamble); those industries can only flourish close to large markets and/or sources of specialist labour. In fact, NZ firms that start out in such areas have to move overseas as they grow.

Our comparative advantage is in agriculture and tourism, as far as anyone can tell. Agricultural productivity has improved to the point that not many people are employed, so further gains will have very little benefit in overall labour productivity. And tourism, like most other service businesses, has limited scope to improve productivity except by raising prices.

My own economic activity illustrates the last point. I run a business consisting of me, with a single overseas client. I charge them by the hour for my time. By definition, the only way to raise my productivity is to raise my hourly rate (which would happen automatically if the NZ dollar falls in value, because I quote my rate to them in USD). In the same way, a hotel cleaner who can clean X rooms on a shift will be more productive if the hotel charges guests $300 a night than if it charges $200 a night, but there seems little scope to raise the cleaner’s productivity otherwise.

So if NZ has a comparative advantage in industries where the scope for productivity gains is small or nonexistent, we should expect long-term stagnation in productivity. But we will make ourselves worse off if we try to muscle in to industries with higher productivity where we have a comparative disadvantage.

So, as I read the statistics that you quote showing our poor and static labour productivity, my reaction is So what: that is what one expects to see in an economy with NZ’s endowments.

LikeLike

Your assessment is wrong. Our comparative advantage in agriculture and tourism is due to heavy government subsidies in this sector. We are actually at a comparative disadvantage but we chose to drop billions of dollars in subsidising this sector. Other countries choose to subsidise heavy industries and manufacturing. Samsung for example was set up with the Korean government subsidising most of the start up costs and till to this day continue to subsidise heavily the continuing growth. The car manufacturing companies in the US has been bailed out by US government subsidies many times over. Malaysia subsidises heavily it’s many manufacturing industries.

Fresh food needs to be close to their markets. So we dry our milk into powder at enormous energy consumption to get our product to market. We have to ensure our shipments of meat and agricultural produce are in refrigerated containers which consume a huge amount of oil. That is why we have to keep our NZD as low as we can so that our farmers can make a margin. We cant get access to US and Europe because our NZD gives us unfair advantage against their local producers, not because we are better quality producers. They get fresh local produce which we cannot deliver due to our distance but we do have a lower NZD and therefore price advantage.

LikeLike

NZ’s comparative advantage in agriculture began with the invention of refrigerated shipping in the second half of the 19th century. One can visit stately houses in the UK where the economic support from the surrounding farmland collapsed in the 1880s as a result of this; a few were propped up by rich industrialists for a while as a hobby, but they were unable to compete with the new sources of cheap food and fibre from the Empire (under very different exchange-rate conditions). Given adequate transport to markets, the source of our comparative advantage is climate and low population density, not subsidies.

Drive around NZ’s countryside and look at the dates on abandoned dairy factories. Once milk could be transported more than a few miles from the farm, we saw huge consolidation of the processors, with corresponding efficiency gains in processing. But it is hard to see much further scope for gains here. On-farm technology also allowed consolidation into larger and more efficient farms, and perhaps there is room to extend that a bit further. But if it only employs a few percent of the population, even doubling the labour efficiency will not make much difference at a national level. There were huge productivity gains, which led to NZ becoming one of the richest countries in the world during our Golden Age after the second world war, but those gains are pretty much played out.

Since subsidies come at the expense of the rest of the society, there is no obvious mechanism by which subsidising selected industries can make the society as a whole better off. It certainly creates a comparative advantage for the industry, but not for the whole country.

So I don’t believe either your economic history or your economics.

LikeLike

Not sure where the history part comes in but it is quite apparent that we have reached peak cow ie peak land use and peak water use and are a major polluter. So we basically cannot add another cow to increase productivity which historically that’s what we have been doing, just allowed our farming herds to get bigger than those in the UK. This year alone we will spend $1 billion on biosecurity as a minimum. That is a subsidy. We do not have a Free Trade agreement with either the US and Europe. Europe has already made clear we lose our export quota when the UK exits. So we are competing based on our lower NZD and not really any other quality. Europe has a abundance of countries that deliver much higher quality products. Nothing to do with economics either. Plain and simple, we make our export margin from trying to get the NZD even much lower than it currently is. 0.69 against the USD and 0.59 against the Euro is already considered too high. If we went for 1 to 1 currency match, our farming exports will be dead in the water, we would not be able to compete. Simple maths.

LikeLike

I only came to a realisation that our NZD is not high and actually way too low. I had thought it high because I have been brainwashed by our economists that go on and on about our NZD currency being too high.

When I visited Italy, Spain, France last year and the USA this year, it dawned on me that our living standards was actually much higher than a lot of those major cities in those major Euro countries and the USA but we kept on and on that our NZD currency was too high. It felt like a complete lie as I had to pay a hefty premium price in Euro and USD for the same meals(usually beef and lamb being my favourite) in similar restaurants due to the NZD being way too low. It quickly dawned on me that we have an unfair pricing advantage on our farming export production due to the low NZD into either the Euro or the USD.

LikeLike

As you know, my story has considerable overlap with what you say: I think it is crazy for politicians to draw more and more people into such a remote location, which has such a poor track record in doing anything much (for global markets) that isn’t natural-resource based. I’m probably more optimistic than you on the possibilities for productivity growth in agriculture and related industries – and thus I would have been fairly optimistic on the income and aggregate productivity prospects for a country of (say) 3 million people here.

LikeLike

Not when 2 million boomers out of the 3 million are headed towards their 70s soon suffering all sorts of ailments. Not a viable option.

LikeLike

It isn’t now – it is just a thought experiment now – but it would have been a viable alternative if started from 1950.

LikeLike

Paul: you make a good case. The argument about distance causing our manufactured good to be more expensive because of the freight costs clearly applies to your example of cars but electronic goods can be produced with minimal frieght costs – for example Nokia. And software has no freight cost and it is fairly easy to sidestep import duties with software sales. Modern delivery means Auckland to London takes about as long as London to a village in the north of Scoland. There is potential for NZ companies with the time difference – effectively we can produce overnight solutions. However we cannot expect our hi-tech businesses to ever be a significant long term solution to our wealth creation problem.

Your point about a cleaner in a tourist hotel makes sense. 55 years ago my mother worked for the Highlands and Islands Development board who were trying to reverse the depopulation of the Highlands of Scotland. They targetted high end tourism because it employs more at higher pay rates and is a little less suspectible to recessions. When I cycled the Otago railroad the organising company emphasised staying at motels and BnB along the way – the last thing they wanted was cyclists with sleeping bags and camp fires. I don’t understand why our govt is so keen to measure tourists by numbers rather than spending. The encouragement of freedom campers seems irrational.

LikeLike

Bob, I was not thinking primarily of freight costs. Consider a company I know of in the finance sector, founded in Wellington but now based in New York. The current CEO has repeatedly testified to Congress about regulation of the industry, and drums up business by speaking to industry meetings around Wall St, and knows who to hire for their sales ability, and is on first-name terms with people who can provide his firm with venture capital. No Wellington-based CEO could possibly do those things.

The reason that many global industries cannot be based in NZ have to do with understanding the local culture, or having gone to school with the CEO of the industry leader, or being able to take a taxi across town to solve a client’s problem, or having your sales people take a quick road trip to the most important of your 300 million European customers. NZ companies struggle with this stuff, not with freight costs.

LikeLike

Bob, given that we import most of our manufacturer products, it is already proven by overseas manufacturers that distance is not a problem in competing with our local manufacturers and beat them hands down in terms of price.

The maths is actually very simple for an IT professional and is actually volume related. Where they a have large domestic markets they can ask for smaller margins. Say I charge $1 margin in a billion people market, I make $1 billion in profit. But in NZ $1 margin only makes me $4.5 million if every man and his dog buys in our NZ market. It is easier to add in a small overseas market like NZ to already a large volume market than it is for a small volume market to try and capture a large billion people market.

LikeLike

Getting product to market is therefore a question of what leading edge product, how to market and how much losses is the company prepared to carry to get into that market. That is why a company like Xero or Rocketlab can access overseas markets. It is new leading edge products that will need to incur upfront costs. New leading edge products don’t have an established market anyway and so does not need to have an established domestic market, which means it will compete to gain market share. It does not matter where the product is manufactured but is does matter than there is a depth of angel funders prepared to be patient about taking losses upfront. In our case it has to be the government as we do not have the depth in terms of the angel investment capital.

LikeLike

That may apply to many companies but NZ only needs to find a few in the minority where these personal contacts don’t matter. The big new businesses such as Amazon, Uber, AirBnB have evolved in a small area of California – not for political or banking connections but for nerd meets nerd reasons (and probably much of that was online).

NZ must have the best travel educated workforce of any country – at the higher level of a business where it is needed NZ has staff who have had extensive OEs. Language works in our favour for knowledge of local cultures but is a disadvantage overall because high-skilled, ambitious and imaginative New Zealanders can find work anywhere in the world and they do so; [if a Kiwi had invented Lego then the company would be in Singapore or somewhere more rational than Denmark or NZ.]

LikeLike

Bob, If we had invented Lego, we would need the funds to expand and volume manufacture to that market on a large scale . NZ does not have expansion funds to build factories and manufacturing equipment. We could build it in NZ if the government assisted with the initial investment and we can ship overseas. Again the proof is that Lego ships its product to NZ easily. So distance is not the issue. Again, it boils down to funding that determines where you set up your fully automated factory. If you need a large cheap labour force then it would be China or Vietnam as Apple CEO argues they can’t do it in US because they need a large labour force. Making Iphones is still labourer intensive.

LikeLike

I wondered if this was related to womens’ participation in the labour force. It’s not, though: all the countries in your group except Ireland had roughly equal proportions of woman to men participating in work. Participation in Ireland was much lower in 1990 but had almost converged to the others by 2017. https://imgur.com/a/aVcd8HG

LikeLike