Eric Crampton of the New Zealand Initiative yesterday sent out a couple of tweets drawn from some pages a reader had sent him from Wellington’s evening newspaper of 18 July 1984. The general election had taken place on the 14th and the foreign exchange market had been officially closed for a couple of days as everyone awaited resolution of the political disputes around who would take responsibility for the by-now-inevitable devaluation. The outgoing (but still caretaker) Prime Minister finally buckled and a 20 per cent devaluation was announced on the 18th. It marked the beginning of almost ten years of pretty thoroughgoing economic reforms, the legacy of which (good and ill) is still with us today.

Anyway, here were Eric’s tweets

(Click on the right-hand side of the first page and you can read a “fake news” story from 1984, how the Evening Post fell for a Michael Cullen hoax press release.)

Eric’s tweets sent me down to the garage and my box of old newspapers from (in)auspicious days. I didn’t have that particular one, but I did find one from a couple of days earlier. In that paper there was an advert for a competition offering as a prize a microwave with a retail value of $1495 – $4800 in today’s money. Whether you run with Eric’s microwave advert or mine, there is no doubt some things are dramatically cheaper (in real terms) than they were then. Of course, for many technology items that will be true everywhere; it isn’t primarily a New Zealand story. Actually, flicking through that old paper it was the car prices that surprised me more: a two-year old Ford Cortina advertised for $18995 ($61000 in today’s money). The New Zealand car assembly industry then really was very heavily protected.

Eric notes “we forget too quickly what a mess the place was in”, which reads a little oddly when he did not, I gather, come to New Zealand for another 20 years. But setting that quibble to one side, and taking on board my own youthful enthusiasm for most or all of the reforms being done at the time (most of which still seem right and/or necessary), I think that with the benefit of hindsight the picture is rather more mixed than perhaps Eric suggests.

On the macro side, the problems were all-too-evident. Fiscal imbalances were large and the balance of payments current account deficit was large. If debt levels (government and external) weren’t that high by the standards which too much of the advanced world has since become used to, they were a huge departure from New Zealand’s post-war experience. Inflation was partially suppressed by a series of freezes – although Muldoon had lifted the price freeze a few months earlier – supported by a series of interest rate controls, which were undoing the partial financial liberalisation of the 1970s. Outside the control of any government, the terms of trade had been trending down for 20 years, and New Zealand material living standards and productivity had been falling behind those nearer the upper ranks of the OECD group. We were still in the construction phase of that disastrous set of wealth-destroying government sponsored energy projects known as “Think Big”. And if protective barriers were slowly being removed – for example, CER was inaugurated the previous year – it was a slow and halting journey at best. High protective barriers not only made many goods unnecessarily expensive to New Zealand consumers, but acted as a heavy tax on actual and potential New Zealand exporters. Much about the tax system was in a mess.

And yet, and yet.

The unemployment rate in June 1984 (from Simon Chapple’s work backdating the HLFS) is estimated to have been 4.4 per cent. Right now it is 4.3 per cent – and 4.3 per cent is well below the average for the last 20 years, while the 1984 was well above the comparable average.

Or house prices. I started looking to buy a first house a few months later, in early 1985. Single 22 year olds could do that sort of thing in those days. Yes, concessional Reserve Bank staff mortgages would have helped, but I recall looking at various houses in Island Bay and Newtown for about $80000. That’s less than $250000 in today’s money. The same houses now look to be perhaps $750000. That mess was created by some of the post-1984 reforms.

Or productivity. In that old newspaper I dug out of the garage I found a post-election op-ed written by Len Bayliss, then a leading New Zealand economist. Among the five major economic challenges he identified for the new government was this

Fifth – extremely poor productivity growth, and more recently GDP growth, have been the subject of a series of economic reports since 1962. As a consequence of this poor performance, other countries’ living standards have risen more than New Zealand’s.

The worst single period for productivity growth in New Zealand history was in late 1970s, but even 35 years ago people knew that the problems were much more deep-seated. Unfortunately, of course, the productivity gaps are now larger than they were in 1984. On OECD estimates of real GDP per hour worked, in 1984 we were close to the levels in Iceland, Ireland, and Finland. These days, we are far behind each of them. We were only about 10 per cent behind the UK in those days, and now they are about 30 per cent ahead of us. Things might not be in such a “mess” nowadays – disorderly macro imbalances and weird interventions – but the economic bottom line still makes sorry reading. No champion of change in 1984, told all the policies that would be adopted and the huge measure of macro stability achieved, would have predicted that we’d have drifted further behind by 2019.

Perhaps especially if they’d been given the additional information of what would happen to New Zealand’s terms of trade over the subsequent decades – the turnaround (outside any government’s control) starting just a couple of years after the reform period got underway.

The devaluation in July 1984 was a huge part of the economic narrative at the time. There was a strongly-held consensus, among local officials, local commentators (it is explicit in that Len Bayliss article) and international agencies, that the New Zealand real exchange rate had become persistently out of line with fundamentals, and that a substantial and sustained depreciation would have to be a significant part of putting the economy on a better-footing. It was, among other things, a repeated and urgent theme of the numerous meetings I attended, as a junior note-taking official, in late 1984.

And here are the two OECD measures of New Zealand’s real exchange rate.

I’ve marked the 1984 devaluation. In real terms, it proved very temporary indeed. It would be great if really strong and sustained productivity growth had supported a structural increase in the real exchange rate. But that, of course, hasn’t been the story. Once we got through the disinflation period – when it was reasonable to expect some temporary periods with a high real exchange rate – it seems to reflect the same sort of domestic demand pressures that have given us persistently among the very highest real interest rates in the advanced world.

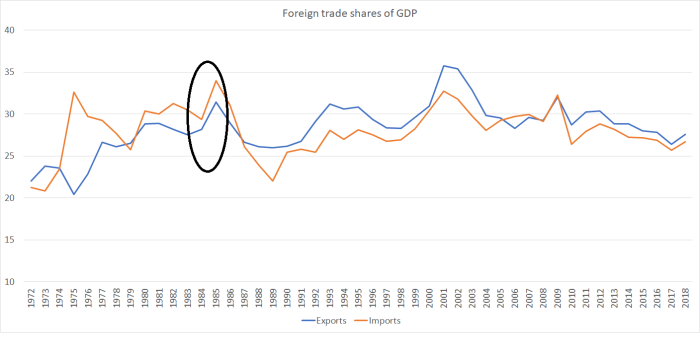

And then there is foreign trade. A narrative at the time was the heavy protection had resulted in New Zealand’s foreign trade shares of GDP falling, or failing to grow. The overvalued exchange rate (see above) further impeded the prospects of potential export industries, probably only partly offset by the various (highly questionable) export incentives and subsidies.

And yet

I’ve circled the data for the years to March 1984 (latest actuals when the devaluation happened) and for the year to March 1985. There was, as you would expect, a short-term boost to the nominal trade shares on account of the devaluation, but of course that didn’t last. But if we take the subsequent 33 years together, there is just no sign of foreign trade having become more important to the New Zealand economy (as it happens, exports as share of GDP in the year to March 2018 were almost identical to those in the year to March 1984). Only one other OECD country has not seen the export share of GDP increase over that time.

I don’t want to kick off a futile debate about whether the reforms should have been done. I’m still squarely in the camp that most should have been. But, equally, nothing is gained by pretending to a degree of economic success we haven’t achieved. We’ve shared – with every market economy (and probably the non-market ones too) – the rapid declines in the cost of various technology goods and services. All of our own doing, we’ve managed to bring about, and sustain, an impressive level of macroeconomic stability. But, equally all of our own doing, we’ve managed to rig the housing market against the current (and next) young generation, and despite reducing or removing all manner of protective barriers (and even getting other countries to do something similar for stuff New Zealand firms exports), foreign trade shares are no higher now than they were on that momentous day in 1984. And, as for productivity, poor – and rightly alarming – as it was then, all indications are that it is worse now, and there are no signs of those gaps beginning to close.

The New Zealand economy isn’t in some disorderly mess at present. But if it is perhaps more orderly, it is failing nonetheless.

I was indeed not yet in New Zealand in 1984. I was, at the time of that newspaper article, finishing up 2nd grade at École élémentaire Notre Dame de Lourdes and looking forward to the summer holidays on the farm.

Arrived in Christchurch in November of 2003.

New Zealand’s rules around housing are in need of some 80s-style reform.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I arrived in early 1987 and joined Fletcher Building’s Property Investment company part of the Fletcher Challenge stable of companies. NZ was a booming economy with Fletcher Challenge being a multinational company and the largest NZX listed company with a diverse portfolio of companies in almost every major production enterprise in NZ of a significant scale.

Jobs were plentiful and with severe labour shortages the NZ Labour government was dishing out unconditional residency amnesties for anyone who wanted residency in NZ. The people queue at the Auckland Central Immigration office was stretched out on the roadside for miles outside of the Immigration office.

Within 3 months a NZ assembled Holden Commodore branded company car was awarded to my remuneration package. A time when NZ had an abundance of highly skilled engineers and we assembled Holden cars with import duties protecting the local NZ car assembly.

My salary increment followed inflation closely with a 22% increase in 1988 a year later and a 8% increase in 1989. Then recession. Don Brash the RBNZ governor at the time always burned black at the back of my mind that he drove and engineered the NZ economic decline. Something to do with raising interest rates.

LikeLike

“…New Zealand’s rules around housing are in need of some 80s-style reform…”

AMEN!

I often post links to this excellent take by Michael R in 2016:

https://croakingcassandra.com/2016/07/28/a-couple-of-cartoons/

I personally came to believe, when Mr Twyford was in opposition, that he was going to be NZ’s housing-policy Roger Douglas. He impressed me with his grasp of the realities of the unintended consequences of urban planning and the layers of statist so-called “solutions”. But once in government, he is just as disappointing as the Nats after 2008, given all the right “pro-reform” noises John Key et al made while in opposition. What is it that gets to these people?

See also my belated comment at the bottom (right now it’s the bottom) of the thread – on 15 Feb.

LikeLike

Interesting, your thoughts on the “Think Big” projects as being wealth-destroying. In my understanding, the “Think Big” natural gas and energy end-use projects were:

A methanol plant at Waitara; an ammonia/urea plant at Kapanui; a synthetic-petrol plant at Motunui; expansion of the Marsden Point Oil Refinery; the Wiri to Marsden Point pipeline; expansion of the New Zealand Steel plant at Glenbrook; electrification of the North Island Main Trunk Railway between Te Rapa and Palmerston North; a third reduction line at the Tiwai Point aluminium smelter near Bluff; and the Clyde Dam on the Clutha River.

Do you think these have in the long-run delivered poor returns to NZ society as a whole?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Exactly. The government of the time employed the resources available to it (including unemployed/underemployed) to build stuff that, a) the private sector couldn’t do or wouldn’t do because it wasn’t profitable, and b) would add to the likelihood of increased productivity, and all this while being constrained in having to accumulate foreign reserves to maintain various pegs. Unfortunately it appears that the government did this to such a degree that it began to compete for real resources against the private sector thus pushing up the general price level (inflation: often misread as a too much money in the economy issue whereas it is actually a real resource allocation issue).

LikeLike

The Clyde Dam project may not have been uneconomic (especially given the population increase – and increased electrcity demand – subsequently put through as immigration policy changed). It was, however, a dodgy project because of the questionable special legislation used to put it in place. Of the others, my understanding is that none of them would have passed any robust cost-benefit analysis assessment (but here I’m drawing on the analysis of others, not my own work).

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, but I’m still curious about the comment “wealth destroying”. Is that a reference to having destroyed public or private wealth; or just a reference to the resultant “currency crisis”?

LikeLike

Wouldn’t have covered the cost of the public or private capital invested in them. (No real connection to the 1984 “crisis”)

LikeLiked by 1 person

In NZ, the government has to think big. It is the only player with the resources to fund future projects of the scale which can make the difference in long term productivity. Unfortunately our think big projects happen to be planting a billion trees or billions in disease control which helps a Primary Industry and gives us a illusion of productivity because we do not count 10 million cows or 30 million sheep with its massive abuse of land, contamination of water and green house gas contaminated atmospheric air resources.

LikeLike

Isn’t our current think big project immigration?

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’ve certainly used that label for it.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Immigration and population growth is the by product of Tourism, international students and a aging population. Immigration is driven by business needs. That is how the skilled migrant category is derived. So it is not appropriate to label it as a government Think big project. The think big project is Tourism numbers at 4 million and the target now is 5 million. I guess economists believe that tourists would grow and cook their own food, clean up their own mess and just live in tents. It is a people business.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Reserve Bank library provided me access to all of their papers on the devaluation crisis and subsequent ‘investigation’ and a couple of years ago I scanned them all and read them carefully.

I think many people have opined on the Exchange Crisis of 1984 without having actually done their homework and the conclusions that many people made – including officials – are wrong.

The two key issues New Zealand faced in 1984 regarding the valuation of the NZD were: i) the expansionary nature of fiscal policy – which expanded the current account deficit and led to an increasing financing requirement, and: ii) the Finance Act (1983) which effectively set ceilings on interest rates. Thus, New Zealand required more funds but those funds couldn’t be willingly provided by the private sector owing to the fact that interest rates were insufficient to offset potential exchange rate risk, and that left the balance of payments precariously placed, essentially stabilised by sovereign borrowing and FX reserve management.

The Labour Party made it very clear to financial market participants that they would devalue and that precipitated a run on the currency. The run on the currency was driven largely by: i) leads-lags in trade flows and hedging and: ii) speculative short NZD exposures in the FX forward market by banks and institutions (which was technically illegal under the Exchange Control Act but I’ve verified that it went on, in size, from market participants at the time). This created a classic currency crisis along the lines of Krugman (1979). Longer term flows caused by the imbalance in the current account exacerbated the issue but did not precipitate it.

Despite the Treasury and the Reserve Bank knowing that a snap election was likely some time in 1984 and that a General Election must be held by end-November, they appear to have been under-prepared for the crisis that took place. They held much of New Zealand’s FX reserves in illiquid assets – a very large JGB position which the Bank of Japan was unwilling to assist us in disposing of – and they did noting to contact either the BIS (who still played a role in those days) and the IMF to provide anchor financing if required (the BIS did help a bit once the crisis started). Consequently, when the run began, the Reserve Bank quickly exhausted its liquid FX positions, started building a large net FX forward position and other tools at there disposal were simply not going to be able to stem the tide of pressure.

Muldoon had many faults. But on the Exchange Crisis I think he was broadly correct. Much of the speculative pressure on the currency was driven by leads-lags in trade flows and speculative activity and these positions must be netted back at some point. Muldoon suggested a joint Muldoon-Lange-Douglas commitment not to devalue and that was widely scorned. The argument run was that the NZD was fundamentally misaligned and that outflow wouldn’t return – it was structural. This proved to be nonsense as the moment the devaluation occurred, capital flowed very rapidly back into the system from offshore as banks and corporations re-adjusted their FX forward positions and spot flows returned (banking the 20% profit). But the devaluation was sufficient to trigger a substantial bout of inflation in 1985 – aided by loosening of price controls (which were necessary) – leading to very high interest rates placing massive pressure on the business sector (esp. farming).

The conclusion I have reached is that the NZD was not fundamentally over-valued in 1984. What we had was inappropriate fiscal policy and interest rate controls.

Moreover, a careful reading of the documents shows that our Public Officials were woeful.

LikeLike

Thanks Peter

I’d have nuanced differences with that take. While there is no doubt that the 1984 “crisis” was a liquidity issue rather than anything more structural – and had there been no election that July there would have been no devaluation that July – I think you are too generous to Muldoon (and I say that as someone who often ends up defending him). As you note, one of the problems was interest rate controls, and he explicitly rejected our early advice (once the run got underway) to remove those controls. Perhaps as importantly, by the Sunday (day after the election) he should have been no more than the person implementing measures determined by the incoming govt. Any Labour Party statement post-election that they wouldn’t have devalued would have been tested extremely quickly and would have been regarded as non-credible. Even had the interest rate controls by then been removed, I suspect we’d have faced something akin to the UK or Swedish situations in 1992 – the interest rates involved in leaning against the outflows wouldn’t have been politically tenable.

My own view that the real exchange rate was structurally overvalued, that one of the mistakes that was made was not to have floated straight away (doing so would have given us immediate control over domestic liquidity), and the other – heart of my hypothesis about underperformance – a little way down the track was opening up immigration which helped mean that our interest rates never converged to those of the world once the disinflation job had been done. Had they done so perhaps something like the RER troughs of the 90s and early 00s might have proved sustainable. (The other, I guess, was not to recognise that massive credit and aset booom to which liberalisation would give rise – although whether it was really foreseeable is perhaps questionable.)

Re the capital flows, what you read and heard squares with some detailed work I and another young grad did in the foreign exchange forms (all hard copies) in late 1984.

LikeLike

Hi Michael,

Yes the Finance Act was a disaster and I agree Muldoon didn’t listen to advice in allowing rates to be liberalised. However, the RBNZ shares some of the blame. They allowed banks to put through transactions that they must have known were in breach of the Exchange Control Act (I know because of my contacts some institutions clearly had no business taking positions (eg foreign hedge funds), they didn’t have a clue on what the nature of the leads-lags in flows were (one of our ex-colleagues who went on to a distinguished career was taken to task by Muldoon on this), they didn’t liquify the reserves and they didn’t discuss any stand-by IMF support. To me that’s pretty damning.

I agree regarding the float. If they’d floated I think the speculative profits would have disappeared very quickly and many speculators would not have had the opportunity to lock down their gains. Also, as you say, we’d have gained control over domestic liquidity conditions and the big inflation of 1985 may have been distinctly smaller.

I’d tend to seperate the Exchange Crisis from the crisis of economic management that we had (and still do to an extent).

LikeLike

Of course, the reserves liquification issue was at least as much (probably more) a Treasury issue. Re lack of knowledge of the leads and lags, that is why we ended up doing the exercise late in 1984.

But I’d agree entirely with your final sentence.

LikeLike

1985 had land prices within the inflation index. It was a mistake by the RBNZ to have engineered the subsequent recession. NZ lost a huge number of highly productive industries as a result of that recession.

LikeLike

In many cases I am not so sure they were highly productive (in the productive/efficiency sense) but we certainly lost a lot of small to medium sized enterprises – many of which (it seem to me anecdotally) were never given the time to adjust to the new ‘shape’ of the market place, and subsequently become more viable in the medium/longer term. What strikes me as very disappointing is that it seems one of the larger negative consequences of economic liberalisation is that we lost the quality of our social capital in engineering. We were world leading in engineering and engineering design prior but the profession seemed to take a big dent/hit in popularity as a result of that economic adjustment.

LikeLike

Fletcher Challenge our largest company of the NZX took a big hit on its profitability due to interest rate exposures and as a result was subsequently broken up into little pieces, asset stripped and sold, as the sum of its smaller parts was higher than the company as a whole.. The Fletcher Building currently on the NZX is only a fifth of the size that Fletcher Challenge used to be. Not only small/medium companies were hit.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Katherine, I think you need to go back to the basic productivity equation and study it. GDP per Capita, is how much is produced versus how many people employed or Michael prefers hours worked. Only automation would give you the highest productivity. It does not matter if there are import duties protecting the industries.

LikeLike

Before the microwave there was the pressure cooker.

LikeLike

It interest me how quickly (comparitively anyway) the collective memory forgets the details that were so important to the cost of things in those days and the memory of the huge financial controls there were on people in this country.

As a teenager living in Christchurch in the late 1950’s where Operation Deep Freeze was based and interested in jazz and getting American records -(virtually unattainable here then) I had managed to get an US $10 note and recall reading with great trepidation how a guy was fined in the court for having US currency in his possession. Later in the 1970’s I imported records from the UK having to buy one 5 shilling postal note at a time from the local post office. Those lucky enough to live in the city could travel around and buy one per post office. You were only allowed one per person per dayper post office. A frend who was of Chinese extraction although as kiwi as the next person was unable to even do that as Chinese were prohibited from buying any at all -somemthing to do with Hong Kong. Most people used the 5/- postal notes to buy jackets from Hong Kong as the local jackets were of such poor quality.

Such details seem absolutely absurd and impossible at this time.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Michael

Clearly history is an area of subjectivity and interpretation.

As someone who was in the money/FX market during the 1984 excitement (at Southpac. Which was how Banks got around inane regulations; by establishing unregulated subsidiaries), I’m not sure there was a great deal of high level economic thinking going on as to the “real” value of NZ$1. The fixed exchange rate mechanism had been a one way bet. Folk such as those at Southpac had found loopholes (eg. the forward exchange market). It was all too obvious what you needed to do to make money… sell Kiwi and buy it back from the RB later.

What got in the way for some people in 1984 was that RB/Douglas dropped the fix.

Illustrative of the shallow thinking, not many of the then punters realized that floating suddenly that meant each private seller had to then find a private buyer. Interest rates went to 1,000% because of the shortage of NZ$.

The break even effect of interest rates at that level was that someone who sold NZ$1 for US$0.40 needed to have the exchange rate fall below 0.34 within a week if they were going to profit. Needless to say, the lesson got through, after about a week.

One other point about your recollection of the past. Our first home in 1982 cost less than 2x our gross income, but interest rates were high teens and thanks to the interest rate regulations (1st mortgage capped at 11%pa.) money was rationed.

Also, while house prices were low, houses were much much more basic. My children may not be able to afford a house as quickly after leaving university as their parents, but their flats are a lot more pleasant than the parents’ owned-home.

Incidentally, I think fish may be the item which has risen in price the most over the last few decades. If you are looking back over the old newspapers, I’d recommend noting the price of snapper and oysters.

Tim

LikeLike

Thanks for those comments Tim. I certainly accept that “houses were more basic” story relative to say my parents’ generation (most first home purchasers bought new Housing Corp financed houses, typically with no landscaping – no lawns, no sealed driveway, no nothing. If I compare my first house (finally bought in 88) with (existing) first houses my siblings in-law (much younger) have finally been buying in the last year or two, I don’t see much difference.

I well remember the 1000% episode in early 85 after the float. When Sweden ran into a crisis in 1992 and short rates got above 500% the more flippant among us were tempted to send the Riksbank a “welcome to the 500% club” card.

You may well be right about fish. Go back far enough – to Dickens etc- and apparently oysters were poor people’s food, despised by those who could afford better. Chicken of course has gone the other way.

Re Southpac, I was rereading my 1984 diary this afternoon and found recorded that shortly after the devaluation people from Southpac came in to the RB to explain financial markets to us economists. i recorded it as a most enlightening session.

LikeLike

the Southpac team never lacked self confidence that they were the smartest guys in the room.

Of course Simon Tyler (who I think will have started about then) later went on to head up the RB dealing team, while Adrian Orr went in the other direction

I note you corrected my “1,000% in 1984” to 1985… yet another example of memory conflating events

LikeLike

Great discussion.

Did anyone at the time dare to suggest that if policies were put in place to increase national saving (not just public, but household and business), the whole exchange rate thing would be less of a source of drama?

LikeLike

I don’t particularly recall, altho at the time the focus was probably on big net public sector dis-saving (and fixing that), and high but poor quality investment (Think Big).

Of course, a few years later – in what was basically a revenue grab – the tax treatment of retirement savings and related products was made much less attractive (arguably worst regime – TTE – in the advanced world).

LikeLike

I would argue that the distortions to urban land values have numerous knock-on effects that are responsible for the underperformance in what seems to be “other areas of the economy”.

The most interesting counter-factual would have been an NZ that was the “Texas of Oceania” for its housing affordability.

The UK has a famous productivity gap, even though it is well ahead of NZ, and the most plausible explanation for the UK’s gap is its urban planning system. There are several books and papers on this by Alan W. Evans and co-authors; and Paul Cheshire and co-authors.

I hold that the damage from similar urban planning distortions will be far more severe for an economy like NZ’s, which does not have the UK’s significant global finance and global media sectors, proximity to large trading partners, national maturity, or population size.

In fact I made a submission to the NZ Productivity Commission on this subject a few years ago.

Click to access Sub%20001%20Phil%20Hayward%20-%20Submission.pdf

And in that submission, I didn’t touch on another significant factor; the diversion of liquid capital away from productivity-increasing capital investments, and into chasing zero-sum speculative gains in unimproved urban property.

LikeLike