In the press release for last week’s Reserve Bank Financial Stability Report, the Governor commented that

Our preliminary view is that higher capital requirements are necessary, so that the banking system can be sufficiently resilient whilst remaining efficient. We will release a final consultation paper on bank capital requirements in December.

In commenting briefly on that, I observed

Time will tell how persuasive their case is, but given the robustness of the banking system in the face of previous demanding stress tests, the marginal benefits (in terms of crisis probability reduction) for an additional dollar of required capital must now be pretty small.

There wasn’t much more in the body of the document (and, as I gather it, there wasn’t anything much at the FEC hearing later in the day), so I was happy to wait and see the consultative document.

But the Governor apparently wasn’t. At 12.25pm on Friday a “speech advisory” turned up telling

The Reserve Bank will release an excerpt from an address by Governor Adrian Orr on the importance of bank capital for New Zealand society.

It was to be released at 2 pm. The decision to release this material must have been a rushed and last minute one – not only was the formal advisory last minute, but there had been no suggestion of such a speech when the FSR was released a couple of days previously.

And, perhaps most importantly, what they did release was a pretty shoddy effort. We still haven’t had a proper speech text from the Governor on either of his main areas of responsibility (monetary policy or financial regulation/supervision) but we do now have 700 words of unsubstantiated (without analysis or evidence) jottings on a very important forthcoming policy issue. which could have really big financial implications for some of the largest businesses in New Zealand and possibly for the economy as a whole.

The broad framework probably isn’t too objectionable. All else equal, higher capital requirements on banks will reduce the probability of bank failures, and so it probably makes sense to think about the appropriate capital requirements relative to some norm about how (in)frequently one might be willing to see the banking system run into problems in which creditors (as distinct from shareholders) lose money. At the extreme, require banks to lend only from equity and no deposit or bondholder will ever lose money (there won’t be any).

But what is also relevant is the tendency of politicians to bail out banks. Not only does the possibility of them doing so create incentives for bank shareholders to run more risks than otherwise (since creditors won’t penalise higher risk to the same extent as otherwise), but there is a potential for – at times quite large – fiscal transfers when the failures happen. Politicians have more of an incentive to impose high capital requirements on banks when they acknowledge their own tendencies to bail out those banks. If, by contrast, they could resist those temptations – or even manage them, in say a model with retail deposit insurance, but wholesale creditors left to their own devices – it would also be more realistic to leave the question of capital structure to the market – in just the same way that the capital structure of most other types of companies is a mattter for the market (shareholders interacting with lenders, customers, ratings agencies and so on).

But nothing like this appears in the Governor’s jottings. Instead, we have the evil banks, the put-upon public and the courageous Reserve Bank fighting our corner. I’d like to think the Governor’s analysis is more sophisticated than that, and one can’t say everything in 700 words, but…..it was his choice, entirely his, to give us 700 words of jottings and no supporting analysis, no testing and challenging of his assumptions etc.

There are all manner of weak claims. For example

We know one thing for sure, the public’s risk tolerance will be less than bank owners’ risk tolerance.

I think the point he is trying to make is about systemic banking crises – when large chunks of the entire banking system run into trouble. There is an arguable case – but only arguable – for his claim in that situation, but (a) it isn’t the case he makes, and (b) I really hope that (say) the shareholders of TSB or Heartland Bank have a lower risk tolerance around their business than I do, because I just don’t care much at all if they fail (or succeed). Their failures – should such events occur – should be, almost entirely, a matter for their shareholders and their creditors, with little or no wider public perspective.

There are other odd arguments

Banks also hold more capital than their regulatory minimums, to achieve a credit rating to do business. The ratings agencies are fallible however, given they operate with as much ‘art’ as ‘science’.

Bank failures also happen more often and can be more devastating than bank owners – and credit ratings agencies – tend to remember.

And central banks and regulators don’t operate “with as much ‘art’ as ‘science'”? Yeah right. And the second argument conflates too quite separate points. Some bank failures may be “devastating” – although not all by any means (remember Barings) – but the impact of a bank failure isn’t an issue for ratings agencies, the probability of failure is. And I do hope that when he gets beyond jottings the Governor will address the experience of countries like New Zealand, Australia, and Canada where – over more than a century – the experience of (major) bank failure is almost non-existent.

The Governor tries to explain why public and private interests can diverge (emphasis added)

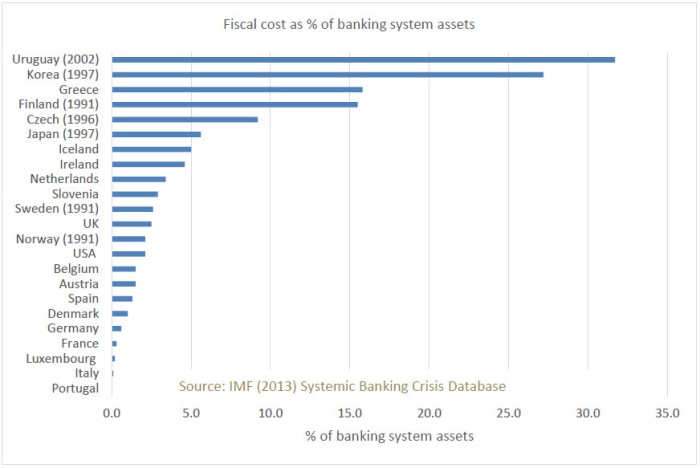

First, there is cost associated with holding capital, being what the capital could earn if it was invested elsewhere. Second, bank owners can earn a greater return on their investment by using less of their own money and borrowing more – leverage. And, the most a bank owner can lose is their capital. The wider public loses a lot more (see Figure 2).

But what is Figure 2?

Which probably looks – as it is intended to – a little scary, but actually (a) I was impressed by how small many of these numbers are (bearing in mind that financial crises don’t come round every year), and (b) more importantly, as the Governor surely knows, fiscal costs are not social costs. Fiscal costs are just transfers – mostly from one lots of citizens (public as a whole) to others. I’m not defending bank bailouts, but they don’t make a country poorer, all they do is have the losses (which have arisen anyway) redistributed around the citizenry. If the Governor is going to make a serious case, he needs to tackle – seriously and analytically – the alleged social costs of bank failures and systemic financial crises. So far there is no sign he has done so. But we await the consultative document.

There is a suggestion something more substantive is coming

We have been reassessing the capital level in the banking sector that minimises the cost to society of a bank failure, while ensuring the banking system remains profitable.

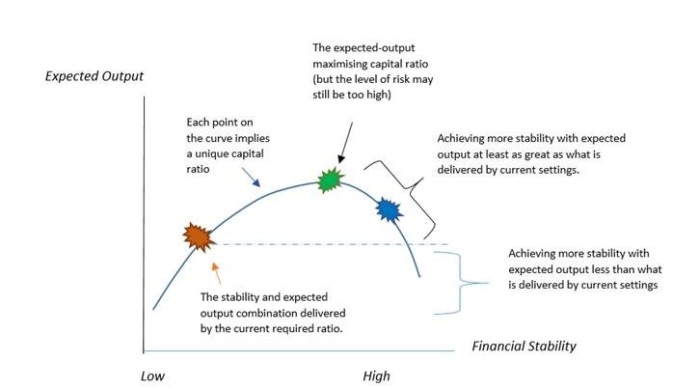

The stylised diagram in Figure 3 highlights where we have got to. Our assessment is that we can improve the soundness of the New Zealand banking system with additional capital with no trade-off to efficiency.

and this is Figure 3

It is a stylised chart to be sure, but people choose their stylisation to make their rhetorical point, and in this one the Governor is trying to suggest that we can be big gains (much greater financial stability, and higher levels (discounted present values presumably) of output) by increasing capital requirements on banks.

I don’t doubt that the Bank can construct and calibrate a model that produces such results. One can construct and calibrate models to produce almost any result the commissioning official wants. The test will be one of how robust and plausible the particular specifications are. We don’t know, because the Governor is sounding off but not (yet) showing us the analysis. Frankly, I find the implied claim quite implausible. Probably higher capital requirements could reduce the incidence of financial crises. But the frequency of such events is already extremely low in well-governed countries where the state minimises its interventions in the financial system, so I don’t see the gains on that front as likely to be large. And, as I’ve outlined here in various previous posts I don’t think that the evidence is that persuasive that financial crises themselves are as costly as the regulators (champing at the bit for more power) claim. And many of the costs there are, arise from bad borrowing and lending, misallocation of investment resources, which are likely to happen from time to time no matter how well-capitalised the banks are.

There are nuanced arguments here, about which reasonable people can disagree. But not in the Governor’s world apparently.

He comes to his concluding paragraph, the first half of which is this

A word of caution. Output or GDP are glib proxies for economic wellbeing – the end goal of our economic policy purpose. When confronted with widespread unemployment, falling wages, collapsing house prices, and many other manifestations of a banking crisis, wellbeing is threatened. Much recent literature suggests a loss of confidence is one cause of societal ills such as poor mental and physical health, and a loss of social cohesion.

Oh, come on. “Glib proxies”…….. No one has ever claimed that GDP is the be-all and end-all of everything, but it is a serious effort at measurement, which enables comparisons across time and across countries. Which is in stark contrast to the unmeasureable, unmanageable, will-o-wisp that the Governor (and Treasury and the Minister of Finance) are so keen on today.

As for the rest, sometimes financial stresses can exacerbate unemployment and the like, but the financial crises typically arise and deepen in the context of common events or shocks that lead to both: people default on their residential mortgages when they’ve lost their jobs and house prices have fallen, but those events don’t occur in a vacuum. And anyone (and Governor) who wants to suggest that mental health crises and a decline in social cohesion can be substantially prevented by higher levels of bank capital is either dreaming, or just making up stuff that sounds good on a first lay read.

The Governor ends with this sentence

If we believe we can tolerate bank system failures more frequently than once-every-200 years, then this must be an explicit decision made with full understanding of the consequences.

As if his, finger in the dark, once-every-200 years is now the benchmark, and if not adopted we face serious consequences. Let’s see the evidence and analysis first. Including recognition that systemic banking crises don’t just happen because of larger than usual random shocks – the isimplest scenario in which higher capital requirements “work” – but mostly from quite rare and infrequent bursts of craziness, not caused by banks in isolation, but by some combination of banks and (widely spread) borrowers, often precipitated by some ill-judged or ill-managed policy intervention chosen by a government. Higher capital ratios just aren’t much protection against the gross misallocations that arise in the process – in which much of any waste/loss is already in train (masked by the boom times) before any financial institution runs into trouble (the current Chinese situation is yet another example).

Perhaps as importantly, under the current (deeply flawed) Reserve Bank Act the choice about capital is one the Governor is empowered to make. But his deputy, responsible for financial stability functions, had some comments to make on this point in a recent speech (emphasis added)

And Phase 2 of the Government’s review is an opportunity for all New Zealanders to consider the Reserve Bank’s mandate, its powers, governance and independence. The capital review gives us all an opportunity to think again about our risk tolerance – how safe we want our banking system to be; how we balance soundness and efficiency; what gains we can make, both in terms of financial stability and output; and how we allocate private and social costs.

It may be that the legislation underpinning our mandate can be enhanced, for example, by formal guidance from government or another governance body, on the level of risk of a financial crisis that society is willing to tolerate.

These are choices that should be made by politicians, who are accountable to us, not by a single unelected and largely unaccountable (certainly to citizenry) official. We need officials and experts to offer analysis and advice, not to be able to impose their personal ideological perspectives or pet peeves on the entire economy and society.

We must hope that the forthcoming consultative document is a serious well-considered and well-documented piece of analysis, and that having issued it the Governor will be open to serious consideration of alternative perspectives. But what was released last Friday – 700 words of unsupported jottings – wasn’t promising.

(I should add that I have shifted my view on bank capital somewhat over the years, partly I suspect as a result of no longer being inside the Bank. It is somewhat surprising how – for all one knows it in theory – things look different depending on where one happens to be sitting. But my big concern at present is not that it would necessarily wrong to raise required bank capital, but that the standard of argumentation from a immensely powerful public official seems – for now – so threadbare.)

It is clear that the Reserve Bank economists need to go back and study Accounting 101 or ensure that they have a highly qualified Chartered Accountant in their key decision making. The amount of Capital has zero bearing on bank stability as it is a historical record of cash initially injected on the formation of the company in NZ. What they need to focus is on the Cash in bank of $2 billion and whether that is sufficient to cover $101 billion in Savings Deposits.

If we review a extract of a banks balance sheet say the ANZ bank in 2017.

Share Capital = $9 billion

Assets

Cash in bank = $2 billion

Lending = $118 billion

Liabilities

Savings Deposit = $101 billion

Share Capital plus Retained Earnings is represented by Assets minus Liabilities which means the focus on Share Capital is just nonsense so forget about the $9 billion in Share Capital it is gone.

The focus needs to be on the Cash in bank of $2 billion and other current assets that can be easily converted to cash.

LikeLike

If the RB says to the ANZ bank that their Share Capital should be $18 billion, it is actually quite easily done without any change in bank stability. eg.

Share Capital = $18 billion

Assets

Cash in bank = $2 billion

Lending = $123 billion (Lend out $5 billion)

Intergroup Advances = $4 billion (Return $4 billion to parent company)

Liabilities

Savings Deposit = $101 billion

As you can see no change in bank stability. The cash received can be easily lent out(say $5 billion) or returned to the parent company(say $4 billion)

LikeLike

It is a rather masochist pleasure to read an article that changes a long held belief. “”we have the evil banks, the put-upon public and the courageous Reserve Bank fighting our corner”” – I’ve believed the first two for most of my life and every advert that portrays banks as generous charitable service organisations reinforces by antagonism. Incidentally taking thie approach that banks are naturally malevolent has saved me a fortune in unnecessary insurance and irrational mortgages. This article has convinced me that banks possess only a (generous) dose of human fraility and are not the product of Lucifer. It made me think and reconsider.

From Mr Orr’s speech “” When confronted with …. collapsing house prices …. wellbeing is threatened. “”. Presumably most of his audience and the majority of people with the spare time to read this article own property, usually their own home. Think about the sizeable fraction of the NZ population who do not own property – they wouldn’t think a collapse in house prices a disaster affecting their wellbeing. To make my point consider my own situation, if all property prices dropped to say 25% of current. Well my wife and I would still be living in a pleasant house and we could still down-size but not make such a significant profit if we did. My investment property would be worth roughly the mortgage on it; of course the rent I charge would have to be reduced since I know the current tentants would move out and buy their own. Among my children the logistic manager and her partner would look to buy whereas at present they are not even bothering to save. The senior social worker would stop sharing a rental and probably buy and then take in lodgers (social workers need company – returning to an empty property at the end of a week is suicidal) and the lowest paid daughter and her partner would move into somewhere larger and give serious thought to having a second child. Finally our apprentice builder son who is clueless about money would probably be able to afford to move out and share with mates – this might improve the well-being of his parents. A long paragraph that says one thing: our society is distorted / hypnotised / obsessed by house prices.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I would welcome a collape of house prices across the board, to a more rational ratio of income to house price, as in former times here…it’s just paper value until you cash up & don’t replace..usually meaning you’re slipped off your perch and so who cares what your home is worth.

LikeLike

It is a worry that the RB does not understand the living standards framework that apparently our govt will be using to plan the next budget.

Published today: https://treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2018-11/lsf-introducing-dashboard-dec18.pdf

Reading it to find out how it applies to the occupants of our house and the all important dashboard splits the populace into two groups of four; the trouble is the groups are of unequal size (ethnicity is European, Maori, Pacifica and Asian which means Africans, Arabs and Americans are simply ignored). Another trouble is you can be a mixture – I think we belong to 6 of the 8 groups. I hate identity being imposed from above (as per Hitler defining who was Jewish) rather than from below as I have moved from identifying with UK to now identifying with NZ.

Planned with good intentions I fear a bag of worms. In practise so long as house prices keep going up then our establishment will assume everything is fine with our wellbeing.

LikeLike

Paper value until you cash up? I think you have your asset values mixed up. Cash is paper value. The value of cash is far more speculative than bricks and mortar houses. The NZD gets its value because currency traders give it value. Overnight it can be worthless. Indian cash holders found recently that their cash became worthless when Prime Minister Narendra Modi gave only four hours’ notice that virtually all the cash in the world’s seventh-largest economy would be effectively worthless.

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-37974423

LikeLike

Orr’s speech after his hot-headed comments at the FSR are interesting not so much for substance. I mean, which Basel III document relies on VAR to calculate capital requirements? Right. However, the announcement of a position, the elevation of capital to the top spot of priorities, and the hurriedly published 2-pager followed shortky after my blog post, which I allowed interest.co.nz to reprint. That post prompted angry responses of some treasurers of big NZ banks. So, yes, it is entirely plausible that Orr moved ahead of Bascand and Bloor and decided to forever end the extremely drawn-oht review of capital. If it were up to Orr, he probably would have published the new capital requirements, but then Bascand and the capital team would have been embarrassed in public.

LikeLike

Granting that the process has been very drawn-out (partly because one Governor was outgoing, his acting successor was both short-term and unlawful, and a new Governor has been in office only for 8 months), I get the sense that we are mostly on opposite sides of this issue. Orr, of course, can’t just lay down new requirements, he has to at least go through the hoops of a public consultative process – and the case to have done so will be stronger the more they publish some decent analysis in support of their position (the 700 words doesn’t qualify!).

For other readers, the posts being referred to are (I deduce)

https://capitalissues.co/2018/11/26/has-the-reserve-bank-become-too-philosophical-about-bank-capital/

https://capitalissues.co/2018/11/30/rbnz-takes-position-on-bank-capital/

As for me, the claim (Orr) that higher bank capital will foster greater social cohesion is a reach altogether too far (like the lamppost and the drunk – used for support rather than illumination).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not a clean process indeed, Orr announcing the capital requirement, sorry, position before the consultation. I mean, with the once in a 200Y position most banks can figure it out.

As for a decent analysis, the requirements in Europe were set at a BCBS meeting in 2010. The idea was 6% CET1 to start with. But Italy did not like that. 4.5% was agreed instead, on the fly, no analysis of sorts. But then came the buffers and Pillar 2, which allowed the regulators to jack up the requirements to near 20% in total. (I am ignoring MREL/TLAC).

These opportunities to a enlarge the capital toolbox have been missed. We did accept the hybrids in Tier 1, which are now a fraction of bank capital in Europe, but here AT1 stands out as an eyesore. Hence the idea to get rid of them, sort of. Instead, the RBNZ could have established buffers and a Pillar 2 framework.

One the time-frame, it has been almost 10 years that BCBS agreed on the definition of capital. Most of the work was done from the April 2009 G20 to December 2009 when the first draft of Basel III was published. Ignore the summer months when Europe is on holiday, and then you will count April, May, June, September, October, November … 6 months to agree on a workable definition of capital.

LikeLike

I guess my comment on timeframes was mostly about the RBNZ’s slow process. I remain a bit sceptical of the case for materially higher capital requirements for the sort of vanilla banks operating here, including because in the NZ context they have the feel of an additional tax on Australian banks relative to local ones. I’d be more indifferent if the trans-Tasman dividend imputation issues had ever been satisfactorily resolved.

But it is a while since I read Admati and Hellwig so I’ve pulled the book down from my shelf to read in conjunction with the forthcoming RB consultation paper.

LikeLike

Please also read some of René Stulz, he is not the Don Quixote that Admati has turned into. René is a much more sensible a scenic, and it beats me why he’s not well known.

LikeLike