Flicking around the web yesterday afternoon I noticed this tweet from Matt Ridley (more formally the 5th Viscount Ridley), the British journalist, businessman and author of various smart books including The Rational Optimist: How Prosperity Evolves. (Ridley was also formerly – from 2004 to 2007 when it hit the rocks – chairman of Northern Rock.)

Ridley is reportedly strongly pro-Brexit. In my book, that is to his credit (had I been British, I’d almost certainly have voted Leave too. Then again, the next recession is likely to shake the euro and the EU itself to its very foundations anyway).

But it was the quote from the paywalled Telegraph article that caught my eye. Those look like pretty impressive numbers, at least for the first 10 seconds until one realises that they are almost certainly total GDP comparisons and British population growth had been faster than that of most of the other countries of Europe. And, of course, polling data suggests that was one of the factors that led to the Leave vote in the first place – in and of itself, higher population growth is hardly a mark of Britain’s economic success, let alone a clear welfare gain for the British.

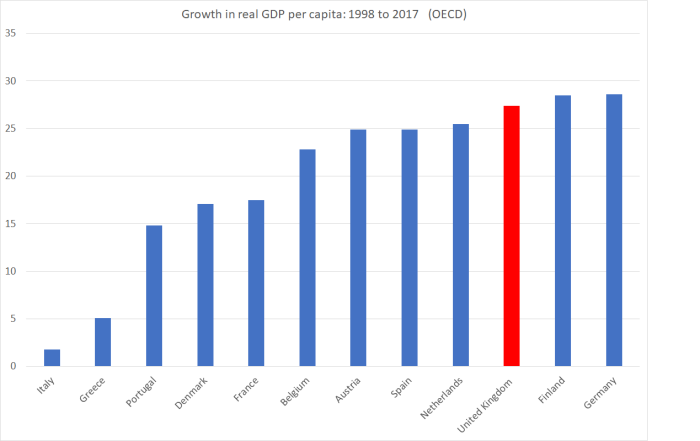

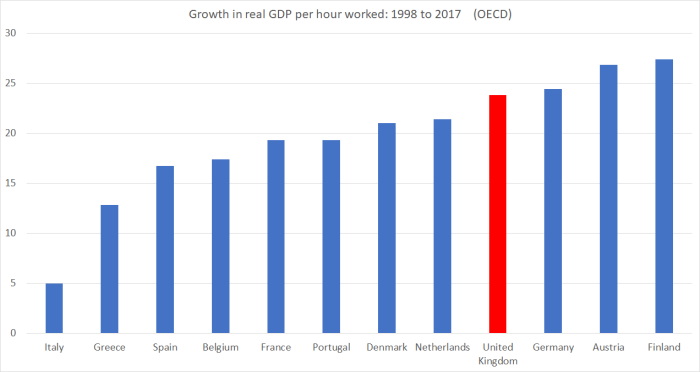

But it left me wondering how the UK had done on other, more relevant, economic comparisons. For example, growth in real GDP per capita and growth in real GDP per hour worked. The euro was launched on 1 January 1999, so here are a couple of comparisons (using annual OECD data) for growth from 1998 to 2017. The comparators are the 10 older western European countries that are in the euro (excluding Ireland whose GDP numbers are messed up by the tax system, and don’t – to a substantial extent – reflect gains to the Irish, and Luxembourg) plus Denmark, which isn’t in the euro but whose currency has been firmly pegged to the euro since its creation. I deliberately didn’t include the former eastern-bloc countries, partly because they joined the euro at various different times over the last 20 years and because something else more important – post-communist convergence – is going on there.)

First, real GDP per capita.

and then real GDP per hour worked.

It isn’t an unimpressive performance over that period as a whole, especially considering (a) all the hoopla at the time the euro was created, including from some trade economists, about the new economic possibilities, and (b) the UK productivity performance since the period encompassing the 2008/09 recession has been really poor (growth in real GDP per hour worked of only 2 per cent in total). And, I guess, it is now more than two years since the referendum, and the real naysayers would have predicted a further worsening in UK productivty growth since then.

Of course, on the other hand, it is fair to point out that the UK is in the bottom half of these countries for its level of productivity. On the OECD estimates, in 2017 only Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece had lower average labour productivity than the UK. But over the 18 years in the chart those laggard countries underperformed, while the UK did actually manage some convergence.

I don’t think these numbers themselves shed any real light on how the UK will do, in economic terms, relative to the rest of western Europe over the next decade or two (whether or not there is the brief, but perhaps initially quite costly, disruption associated with a “no deal”). And it is interesting just how widely performance has diverged even among countries in both the commmon currency and the single market. People make choices about nationhood, and how they want their country run, for a whole variety of reasons, and in most cases a few percentage points of GDP either way doesn’t weigh that heavily – as I’ve pointed out previously, many post-colonial countries (notably in Africa, but including Ireland) underperformed economically after independence, but probably few really regretted the choice of becoming independent. Brexit won’t change the twi n facts that the UK is a moderately prosperous country, nor the fact that – inside or outside the EU – it has productivity challenges, if it wishes ever again to be in the very front rank of economic performance.

I attended a lecture a couple of weeks ago by the historian and “public intellectual” Niall Ferguson. He noted that he had supported Remain, for what seemed to be not entirely serious reasons (he is/was friends with David Cameron and George Osborne and thought they were doing a good job, and was himself going through a messy divorce and thought breakups were very hard). But he had become frustrated by what he described as “the bleating, whining, grumbling of the Remainers” and suggested that he now supported Brexit for two reasons. The first was that, in his view, the EU could only survive if it became more like a federal state (good luck with that) and the UK could never have been a part of such an entity. And the second was a hope that Brexit would help the UK confront the fact – captured in the data above – that its economic challenges are there whether or not it is in the EU.

I was reading last night an 1882 lecture by French philosopher and historian Ernest Renan, titled “What is a nation?”. It seemed relevant at present, emphasising as he does that nationhood isn’t about race or language, but about two things

One is the past, the other is the present. One is the possession in common of a rich legacy of memories; the other is present consent, the desire to live together, the desire to continue to invest in the heritage that we have jointly received. Messieurs, man does not improvise. The nation, like the individual, is the outcome of a long past of efforts, sacrifices, and devotions. Of all cults, that of the ancestors is the most legitimate: our ancestors have made us what we are.

A nation is therefore a great solidarity constituted by the feeling of sacrifices made and those that one is still disposed to make.

and

Nations are not eternal. They have a beginning and they will have an end. …..At the present moment, the existence of nations is a good and even necessary thing. Their existence is the guarantee of liberty, a liberty that would be lost if the world had only one law and one master. By their diverse and often opposed faculties, nations serve the common work of civilization. Each carries a note in this great concert of humanity, the highest ideal reality to which we are capable of attaining.

That makes sense to me. As does, through all its challenges and mismanagement, Brexit.

My take on Brexit is that while people focus on the racial undertones of those who supported it, there are other quite fundamental reasons for it.

Firstly, democracy. The UK has a long history of democracy stemming back through the reform acts to the Civil war and back to Magna Carta. The EU’s experience with democracy is generally quite recent – many nations in the EU were not democratic in most of our lifetimes and some are moving in the wrong direction (Poland and Hungary). EU institutions aren’t especially democratic and I believe the UK still has a deep fear of domination from the continent (continental entanglements have never gone well).

Secondly, the EU is based on Napoleonic/Roman law not English Law. I think this is a major point that’s often overlooked but it comes back to the average English person’s view of freedom and fairness.

Finally, the UK entered a trade agreement in the 1970’s not a political union. The political union was forced on the European family by Jacques Delors with the Maastricht Treaty; a treaty that should have only been enacted in the event of favourable plebiscites, which never happened.

So there are good solid reasons why you’d want to be a Brexiter and not merely racist ones.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Good comments. I used to live in the UK and now in Germany and get asked by family and friends in NZ/Aus about Brexit, with an implicit assumption that is a totally mad idea, and probably a proto-fascist movement. This is reflective of the coverage that trickles down(under) from the UK left wing press I guess.

I point out the issues are more complex – deep constitutional ones are big drivers for most Brexit supporters, particularly the more thoughtful ones (immigration is just a topical symptom of those debates). Statist social democracy may be a legitimate option for government in a democracy from time to time, but the EU pretty much bakes this in as permanent, no matter who you elect in the UK.

26/28 (not Ireland) of the members are social democractic, Napoleanic code, big state countries which explains why. The EU just reflects their day to day political experience, but on a macro scale. An excellent book on this is “Berlin Rules” by Paul Lever – he carefully matches the various EU institutions and their functioning to corresponding German parts (Germany being a dominant and long term member of the group).

Germans I live with simply cannot understand the UK’s dislike of the EU – what’s not to like? Someone in Germany was always going to micro manage your life anyway, it just happens to be a different someone, and in the German case the EU at least makes them feel like they are doing something to assuage their guilt over the past. Cynical horse trading behind closed doors is an accepted part of political and economic life here and most other EU states, but crucially always to expand the state’s power (our complaint usually is lobbyists push to liberalise regulations). You regulate my sector to protect me and I’ll help regulate your sector – these are the big complaints from the British about Europe. The EU have been worried about a post-Brexit ‘race to the bottom’ but ignore the very real regulatory race to the top within the EU – each corrupt and inefficient regulation at local level tends to get pushed to EU federal level to ensure no one gets an ‘unfair advantage’.

And as you say, the overall public spirit of the average British or New Zealander is somehow fundamentally against this – which I think explains Thatcher, Roger Douglas. It’s not just the economics, but also a tendency towards freedom and antipathy to bloated, permanent bureaucracy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Also, I think – as New Zealanders need to learn – there are more important fundamentals than just “the trade”. The UK has struggled in the EU/EEC (winter of discontent) and boomed. It has struggled independently, and boomed. What matters are the policies and structure of the UK economy, it’s resource endowments and incentive structures.

If these are good, the UK can prosper outside the EU. If not, it won’t.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not sure if Brexit is a goer or a goner. Teressa May is certainly feeling the pressure and may have to resign soon.

LikeLike

I voted ‘Remain’. It seemed to be a head / heart decision. The heart said leave for all the reasons outlined by Peter plus as an Englishman I’m proud of the my English (note not British), heritage and moderation. However my head said states trade with proximate states, the country is inextricably intertwined with Europe, and the Brexiteers are clearly wrong in many of their claims, ease of getting out, 350 million pounds to NHS, etc.

If there’s a second referendum – to be frank, currently I don’t know which way I’ll vote.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Renan quote, for me, is also relevant to NZ. For the history of the islands since human occupation, there has been a pattern of short term booms based on resource exploitation (moa, kauri, sheep etc) and a reluctance to invest to put down deep roots that create lasting value. The current immigration/land bubble is just another manifestation of that, enabling a lot of people to make a quick buck doing basically nothing and then basically retire. Another strand of the community has tried to engage in “a long past of efforts, sacrifices, and devotions” but they are not winning at the moment. The productivity statistics are the evidence. (And I doubt we would have been on the right hand side of the GDP per hour worked chart above).

LikeLike

On your final point, we fall between Portugal and Denmark on that measure (our new really poor period has been the last five years).

I also thought Renan’s ideas were relevant to thinking about NZ, altho for slightly different (probably overlapping) reasons.

LikeLike

An article that made me think about the meaning of nation.

“” By their diverse and often opposed faculties, nations serve the common work of civilization. “” That could be the start of an interesting essay.

“” One is the possession in common of a rich legacy of memories; the other is present consent, the desire to live together “” this sounds like something Noah Hariri would write.

Wittgenstein argued that things which could be thought to be connected by one essential common feature may in fact be connected by a series of overlapping similarities, where no one feature is common to all of the things. His classic example was the word ‘Game’; that is a useful word we all understand but cannot actual define with a unique set of attributes. ‘Nation’ is the same; there is not a single set of NZ values.

See John Tamihere on ‘What is a New Zealander?’ https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=12140190

LikeLike

Would that be a hard Brexit or a soft brexit?

There is a world of difference

LikeLike

Depends a bit on what you mean by the terms. I assume that 20 years from now the UK will have tariff-free and mostly NTB-free entry to major European markets for goods and most services (unless of course the EU itself has split up and everyone has drifted back to protectionism – in which case whether the UK leaves now or at the break-up point), with some treaty-based regulatory harmonisation (as for example under CER).

Some forms of soft Brexit seem worse than the status quo, because in many respects the UK is constrained by the rules, but has no influence (legally) over them.

LikeLike

soft brexit that is a customs union is assumed.

Yep the costs would be lower as Kruggers has pointed out ( so has simon as well).But there are stil costs.

The Brexiteers want a hard brexit. NO customs union which vastly increases the costs.

LikeLike

The data certainly doesn’t show the UK suffered relative to core EU countries during the period it has belonged. The counter-factual of how it would have performed had it not joined the EU is unknown. It would be interesting to see how the EU as a whole performed relative to other OECD nations over the period to gauge whether the UK hitched its wagon to a dull star. As an economic union I believe it has failed and benefited Germany versus the periphery. However the EU was primarily a political union to avert wars so a lacklustre performance economically is of secondary importance. The EU is certainly not a nation in the sense Renan describes so it seems destined to flounder along or collapse rather than become a federal state. In those circumstances, Brexit is clearly preferable.

LikeLike

If anyone missed it, I thought this was an interesting point of view the more potent having been written by an Englishman in a sober journal of capitalism.

Politicians and voters alike have nourished delusions about the nation’s global role

In one sense, Boris Johnson is right. The Brexit process has indeed felt like a national humiliation. How many Brits have felt our innards shrivel at key moments of the negotiations? And I am not talking about the incidents of diplomatic bumbling, of unwarranted second world war references and Dad’s Army condescension. I am talking about the parts of this process that have gone as predicted. Perhaps we should step back from the bloviated rhetoric. Humiliation is too strong; a national humbling is more accurate. The philosophy of Brexit was that, freed of EU constraints, the UK would take its rightful place in the world. This is indeed what is happening, but alas that place is not as the great power of their imagination. The UK’s place in the world is hardly terrible but, as Mr Johnson learnt during his brief but undistinguished term as foreign secretary, our emissaries no longer bestride summits like Castlereagh. For far too long British politicians, journalists and voters have enjoyed a patently distorted vision of the nation as indispensable world player. Now the nation is facing the painful truth that the UK is not as pre-eminent as it has liked to believe. For proof, look at the negotiations over the Irish border. One need not get into the rights and wrongs to see that the UK has essentially been pushed around by Ireland, because the EU has thrown its weight behind the demands of its continuing member. The hard fact is that the power imbalance has meant the UK is being forced to choose between the chaos of a no-deal Brexit or undermining the constitutional integrity of one of its four sovereign parts and signing up to a significant amount of rule-taking. This is what happens when a single country that is not America or China negotiates with a global trading bloc. From the sequencing of the negotiations to the empty scorecard of British wins, the entire process has been a lesson in power politics. Few who saw the TV programme on America’s London embassy will forget the smirks as an US official described the British Brexit delusions: “They sort of see it as a negotiation between two equal parties.” One should not overstate this. Britain is not Latvia. It still carries heft. It is a top 10 global economy (fifth, sixth or ninth depending on the market and your choice of methodology). It remains a military power, with a nuclear deterrent and a seat on the UN Security Council. It is the only European nation with access to US intelligence through the “five eyes” programme. Its pre-eminence as a financial centre will not immediately be dissipated by Brexit. The UK will still get its call, but after France and Germany and just before Canada. Life in the top 10 is different to life in the top three. Much of the UK’s global clout derived from its being one of the big nations of the EU. Margaret Thatcher used that very platform to help create the single market, drive forward global trade and entrench democracy in eastern Europe. The 1970s champions of Britain’s membership were right in arguing that the alternative to pooled sovereignty was not more influence but less. Now Britain is about to taste life as one of the loudest of the next level of voices. In this tier, maintaining influence beyond military matters, requires the painstaking unbombastic alliance-building that saw its existing political and diplomatic practitioners so derided as sell-outs by our chauvinistic MPs and media. It might, for example, mean expediting entry permits for Moldovan trade representatives so they do not delay the UK’s ambitions at the World Trade Organization. And how will the UK’s status be reflected in its new trade deals? One has only to look at Donald Trump’s treatment of Canada to see that his negotiators will offer no special favours to the UK. Mr Trump is pro-Brexit because he wants to see a weakened EU, not to play benefactor to the UK. EU nations will be similarly cut-throat. Nor will sentimental attachments affect Commonwealth nations. Too many Brits fail to grasp that former colonies do not look back to the empire with unalloyed affection. While this has all been understood by serious figures in government, too much of Britain’s politics, culture and its self-image have been driven by its colonial past and the national myths built up around the last war. It is why the Brexiters cling so desperately to the theory that Theresa May has betrayed Brexit. The alternative is to accept that it is their own reckless chauvinism that has reduced the UK to the role of supplicant with its former partners. Adjusting to a reduced status will require a reality check in our media and our politics and a touch of humility. If Brexit helps the UK come to a more accurate realisation of its global significance, some good may yet come out of this wretched business. Still, it seems an expensive way to learn a lesson. robert.shrimsley@ft.com

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think in a hard Brexit WTO environment the UK would do okay but I don’t think there are vast gains to be made from de-regulating. The big areas the UK makes money from are heavily regulated anyway (pharma, finance, weapons). However, the direction of travel for the EU is always towards more regulation, and they grow emboldened with each step – we can’t know today what nascent industry they will try to regulate into an early death but at least the UK would be free (in hard Brexit mode) to pick up the economic refugees.

Speaking only idealistically, a hard Brexit environment may inspire a more swashbuckling entrepreneurial spirit among the citizens of the UK, away from the morbid continental obsessions of early retirement and secure life long employment in industrial conglomerates. Hard to predict that one, especially if Corbyn is standing by to take over.

What should not be overlooked is the zealousness that the EU will pursue pain and humiliation for the UK if they went with a hard Brexit. Even if the costs are high, they are likely to pursue masochistic policies that hurt both, just to prove a point. Difficult to say how bad this could be (closed channel ports for six months??).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Imperfect memories

Prior to UK joining the European Union, NZ enjoyed a privileged position with the UK exporting much of its Butter, Cheese and Lamb. To the extent the UK represented “the market” for NZ. At the same time, prior to UK’s entrance, small lot farmers in France with 5 acres and 5 cows made a satisfactory living based on the subsidies they received. It was called the Common Agricultural Policy or CAP. On entry to the EU, NZ lost that privilege. Today the CAP subsidies are still going, amounting to 35% of the total budget spend

It could and should be that on exit (Brexit) the UK will undertake new FTA’s with AU,NZ, and CA

Perhaps NZ will become wealthy again

LikeLike