Browsing on The Treasury’s website the other day, it was the title that caught my eye: “Talkin’ about a revolution”. I’m rather wary of revolutions. Even when – not always, or perhaps even often – good and noble ideas help inspire them, the outcomes all too often leave a great deal to be desired. There are various, quite different, reasons for that, but one is about the failure to think through, or care about, things – themselves initially small or seemingly unimportant – that the revolution opens the way to.

This particular “revolution” – billed as “a quiet and sedate revolution, but a revolution nonetheless” – was sparked by Statistics New Zealand’s Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI). Here is the Treasury author

The creation of Stats NZ’s IDI (or Integrated Data Infrastructure), a treasure trove of linked data, sparked the revolution, and its ongoing development drives it along. The IDI doesn’t collect anything new. Instead it gathers together data that is already collected, links it together at a person level, anonymises it, and makes it available to researchers in government, academia, and beyond.

The author goes on

Since 2013, its growth has been far more rapid. From a handful of users in its early years, there are now hundreds of people using IDI data to help answer thorny questions across the full range of social and economic research domains. The IDI is incredibly powerful for research, and has a number of important strengths.

- Longitudinal – Providing a picture of people’s lives over time, crucial for understanding the effect of policies and services.

- A full enumeration – Incorporating administrative data for almost all New Zealanders, enabling a focus on minority groups and small geographic areas.

- Accessible – By making data available to researchers at relatively low cost, agencies are no longer gatekeepers of the data they collect, and a culture of sharing in the research community is encouraged.

- Cross-sectoral – Allowing researchers to explore the relationships between different aspects of people’s lives that may be invisible to individual agencies.

There is a breathless enthusiasm about it all.

Stats NZ’s new online research database highlights the huge breadth of research underway for the benefit of all.

It is never made clear quite how the Treasury author gets to his conclusion that all this research benefits us all.

And here is the SNZ graphic illustrating the range of data they have put together (and linked)

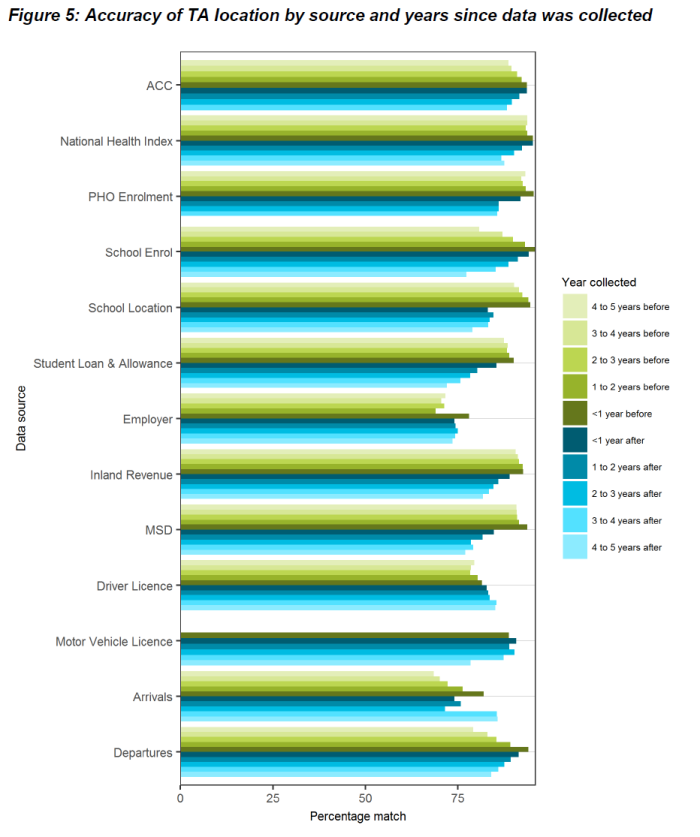

I’m a bit torn about the IDI (and its business companion, the LBD). As an economist and policy geek, I’m fascinated by some of results researchers have been able to come up with using this new database. A few months ago I wrote (positively) here about how Treasury staff had been able to derive new estimates on internal migration. Here is a chart I showed then on the various databases linked together that enabled those estimates.

And here is a more-detailed SNZ graphic on what data are in the IDI at present (and more series are still being added).

More details are here.

Note that it is not even all government data – for example, the Auckland City Mission is providing data on people it assists. Specifically

Auckland City Mission data

Source: Auckland City Mission

Time: From 1996

What the data is about: Income, expenses, housing status, and household composition of Auckland City Mission clients, and the services these clients use. Auckland City Mission is a social service provider in Auckland CBD, that helps Aucklanders in need by providing effective integrated services and advocacy. Note: data dictionary available on the IDI Wiki in the Data Lab.

Application code: ACM

Even if in 1996 those individuals gave their consent for their (anonymised) data to be used, few people in 1996 would have had any idea of the practical linking possibilities in 2018. (And at a point of vulnerability how much ability did they have to decline consent anyway?)

It is researcher heaven. But it is also planner’s heaven.

Statistics New Zealand sings the praises of the IDI (as does Treasury – and any other agency that uses the database). I gather it is regarded as world-leading, offering more linked data than is available in most (or all) other advanced democracies – and that that is regarded as a plus. SNZ (and Treasury) make much of the anonymised nature of the data, and here I take them at their word. A Treasury researcher (say) cannot use the database to piece together the life of some named individual (and nor would I imagine Treasury would want to). The system protections seem to be quite robust – some argue too much so – and if I don’t have much confidence in Statistics New Zealand generally (people who can’t even conduct the latest Census competently), this isn’t one of the areas I have concerns about at present.

But who really wants government agencies to have all this data about them, and for them to be able link it all up? Perhaps privacy doesn’t count as a value in the Treasury/government Living Standards Framework, but while I don’t mind providing a limited amount of data to the local school when I enrol my child (although even they seem to collect more than they need) but I don’t see why anyone should be free to connect that up to my use of the Auckland City Mission (nil), my parking ticket from the Dunedin City Council (one), or (say) my tiny handful of lifetime claims on ACC. And I have those objections even if no individual bureaucrat can get to the full details of the Michael Reddell story.

The IDI would not be feasible, at least on anything like its current scale, if the role of central government in our lives were smaller. Thus, the database doesn’t have life insurance data (private), but it does have ACC data. It has data on schooling, and medical conditions, but not on (say) food purchases, since supermarkets aren’t a government agency. I’m not opposed to ACC, or even to state schools (although I would favour full effective choice), but just because in some sense there is a common ultimate “owner”, the state, is no reason to allow this sort of extensive data-sharing and data-linking (even when, for research purposes, the resulting data are anonymised). There is a mentality being created in which our lives (and the information about our lives) is not our own, and can’t even be stored in carefully segregated silos, but is the joined-up property of the state (and enthusiastic, often idealistic, researchers working for it). We see it even in things like the Census where we are now required by law to tell the state if we have trouble “washing all over or dressing” or, in the General Social Survey, whether we take reusable bags with us when we go shopping. And the whole point of the IDI is that it allows all this information to be joined up and used by governments – they would argue “for us”, but governments view of what is in our good and our own are not necessarily or inevitably well-aligned.

In truth my unease is less about where the project has got to so far, but as to the future possibilities it opens up. What can be done is likely, eventually, to be done. As I noted, Auckland City Mission is providing detailed data for the IDI. We had a controversy a couple of years ago in which the then government was putting pressure on NGOs (receiving government funding) to provide detailed personal data on those they were helping – data which, in time, would presumably have found its way into the IDI. There was a strong pushback then, but it is not hard to imagine the bureaucrats getting their way in a few years’ time. After all, evaluation is (in many respects rightly) an important element in what governments are looking for when public money is being spent.

Precisely because the data are anonymised at present, to the extent that policy is based on IDI research results it reflects analysis of population groups (rather than specific individuals). But that analysis can get quite fine-grained, in ways that represent a double-edged sword: opening the way to more effective targeting, and yet opening the way to more effective targeting. The repetition is deliberate: governments won’t (and don’t) always target for the good. It can be a tool for facilitation, and a tool for control, and there doesn’t seem to be much serious discussion about the risks, amid the breathless enunciation of the opportunities.

Where, after all, will it end? If NGO data can be acquired, semi-voluntarily or by standover tactics (your data orno contract), perhaps it is only a matter of time before the pressure mounts to use statutory powers to compel the inclusion of private sector data? Surely the public health zealots would love to be able to get individualised data on supermarket purchases (eg New World Club Card data), others might want Kiwisaver data, Netflix (or similar) viewing data, library borrowing (and overdue) data, or domestic air travel data, (or road travel data, if and when automated tolling systems are implemented), CCTV camera footage, or even banking data. All with (initial) promises of anonymisation – and public benefit – of course. And all, no doubt, with individually plausible cases about the real “public” benefits that might flow from having such data. And supported by a “those who’ve done nothing wrong, have nothing to fear” mantra.

After all, here the Treasury author’s concluding vision

Innovative use of a combination of survey and administrative data in the IDI will be a critical contributor to realising the current Government’s wellbeing vision, and to successfully applying the Treasury’s Living Standards Framework to practical investment decisions. Vive la révolution!

Count me rather more nervous and sceptical. Our lives aren’t, or shouldn’t be, data for government researchers, instruments on which officials – often with the best of intentions – can play.

And all this is before one starts to worry about the potential for convergence with the sort of “social credit” monitoring and control system being rolled out in the People’s Republic of China. Defenders of the PRC system sometimes argue – probably sometimes even with a straight face – that the broad direction of their system isn’t so different from where the West is heading (credit scores, travel watchlists and so). That is still, mostly, rubbish, but the bigger question is whether our societies will be able to (or will even choose to) resist the same trends. The technological challenge was about collecting and linking all this data, and in principle that isn’t a great deal different whether at SNZ or party-central in Beijing. The difference – and it is a really important difference – is what is done with the data, but there is a relentless logic that will push erstwhile free societies in a similar direction – if perhaps less overtly – to China. When something can be done, it will be hard to resist eventually being done. And how will people compellingly object when it is shown – by robust research – that those households who feed their kids Cocopops and let them watch two hours of daytime TV, while never ever recycling do all sort of (government defined – perhaps even real – hard), and thus specialist targeted compulsory state interventions are made, for their sake, for the sake of the kids, and the sake of the nation?

Not everything that can be done ends up being done. But it is hard to maintain those boundaries, and doing so requires hard conversation, solid shared values etc, not just breathless enthusiasm for the merits of more and more linked data.

As I said earlier in the post, I’m torn. There is some genuinely useful research emerging, which probably poses no threat to anyone individually, or freedom more generally. And those of you who are Facebook users might tell me you have already given away all this data (for joining up) anyway – which, even if true, should be little comfort if we think about the potential uses and abuses down the track. Others might reasonably note that in old traditional societies (peasant villages) there was little effective privacy anyway – which might be true, but at least those to whom your life was pretty much an open book were those who shared your experience and destiny (those who lived in the same village). But when powerful and distant governments get hold of so much data, and can link it up so readily, I’m more uneasy than many researchers (government or private, whose interests are well-aligned with citizens) about the possibilities and risks it opens up.

So while Treasury is cheering the “revolution” on, I hope somewhere people are thinking harder about where all this risks taking us and our societies.

I wrote about the risks of this here: http://kiwiwit.blogspot.com/2017/04/governments-use-of-data-is-scary.html. I know (from the work I have done in the area) that the agencies involved have no understanding (or wilful ignorance) of the risks involved. There have been numerous cases overseas of third parties such as insurance companies de-anonymising the data (which is easy enough to do if you have a large database of your own clients and access to about 4 or 5 identifying variables). Note the UK care.data (similar to the IDI but focusing solely on health data) report that I reference: https://techscience.org/a/2015081103/.

LikeLike

Thanks for the interesting links.

LikeLike

Sorry but that’s impossible in IDI. First up, they’d never let insurance companies in through the door. You have to be an approved research organisation, and that’s not an easy process. After you have that, you have to have the project approved. And that’s not an easy process.

But suppose that an insurer got somebody with existing IDI access to try and do something for them. What then? You can’t take anything out of the lab without it being checked. All output goes through their data checkers and they are insanely paranoid on anything that might potentially identify.

You give an example of an insecure MSD terminal – access to IDI is never through those sorts of things. It’s a closed system.

The only way insurers get access to the data is if the government makes a policy decision to give it to them, and even then Stats wouldn’t make it easy.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Utopia, you are standing in it!.

LikeLike