For small countries in particular, foreign trade is a key element in economic prosperity. Firms in your country develop products and services that people abroad want, and that enables your citizens to consume from the wider range of products and services the rest of the world has to offer. It isn’t just final products, but trade in intermediate goods and services (inputs to other production) also enables specialisation and the general gains from trade.

Foreign trade wasn’t always important in the islands of New Zealand. For the centuries after first settlement there was none. And (although not solely for that reason) the people – Maori – were poor. In modern New Zealand, foreign trade has been critical: 100 years ago there was a widely cited claim that New Zealand did more foreign trade per capita than any other country. Hand in hand with that, we were among the countries with the highest incomes per capita.

But no longer, on either count.

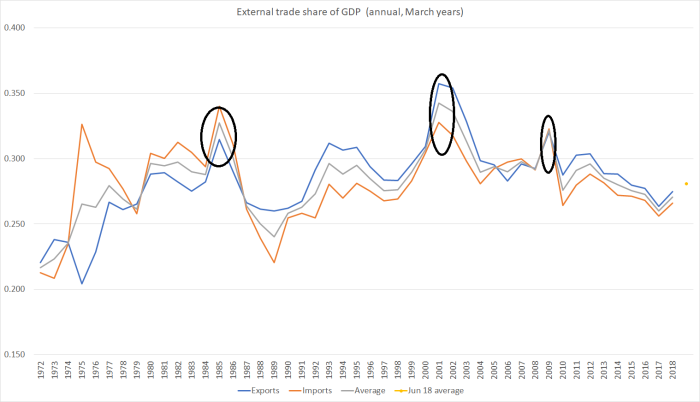

The latest quarterly numbers out last week did show an uptick in both exports and imports as a share of GDP. But here is the chart back to 1972 – annual data, plus the latest quarterly observation.

The foreign trade share has been, at best, static for almost 40 years (in most countries they’ve been increasing). The last few years have seen the trade share the weakest for almost 30 years (and the late 80s construction boom). I’ve highlighted the only three occasions when exports and imports have averaged 30 per cent or more of GDP: the year to March 1985, the years to March 2000 to 2002, and the year to March 2009. What was the common feature of those years? It wasn’t the stellar success of outward-oriented businesses. It was the (unexpected) severe weakness in the exchange rate: the devaluation of 1984, the period around the end of the dot-com boom when US interest rates were high, and New Zealand (and Australian) dollars were unattractive, and the international financial crisis (and extreme risk aversion) of 2008/09. Based on the rest of the set of New Zealand policies, those low exchange rates weren’t sustainable, and there was a relatively quick rebound.

What of other advanced countries?

Big countries tend to do less foreign trade (share of GDP) than small countries. That is no surprise, as there are many more markets and opportunities for specialisation (gains from trading) close to home. Here are the OECD countries that in 2016 (last year with complete data) had exports and imports averaging less than 30 per cent of GDP.

| Australia | 21.0 |

| Chile | 27.8 |

| Italy | 29.0 |

| Israel | 28.2 |

| Japan | 15.6 |

| Turkey | 23.4 |

| UK | 29.1 |

| USA | 13.3 |

Of them, Italy, Japan, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States are big countries and big economies. You’d expect to find them on this table, and if anything the anomaly is Germany, with a foreign trade share now in excess of 40 per cent of GDP.

Of the remaining countries, there are

- Australia, with five times our population,

- Chile, with more than three times our population, and with the second lowest labour productivity in the OECD (beating only Mexico), and

- Israel, which isn’t much larger than New Zealand but which – as I’ve highlighted here previously – has a similarly lousy productivity growth record.

And all, in one form or another, with severe disadvantages of distance.

There has been a tendency in some circles to excuse New Zealand’s low foreign trade shares by citing distance, but simultaneously a reluctance to take seriously what is implied by that limitation. If the opportunities for foreign trade from this remote location don’t look particularly good, isn’t there something deeply illogical (or worse) about continuing to use policy (as successive governments have done for last 25 years) to drive up our population – more people in an unpropitious location? All the more so when adopting that policy approach also involves driving the real exchange rate up, away from where it would likely settle otherwise. Not all New Zealanders suffer in the process – if you run a business geared, in effect, solely towards population growth you may well flourish – but New Zealanders as a whole have.

For all the occasional talk about rebalancing the economy (from both main parties, at least when they first take office) none of it seems to take any serious account of this constraint. Which is only set to become more seriously as – relative to other countries – the opportunities here shrink with the apparent determination to pursue net-zero emissions targets. Planting (lots more) is unlikely to be a path to sustained prosperity or higher productivity.

These days, New Zealand’s per capita foreign trade will among the lowest in the advanced world. Among the rich countries, only (very big) Japan and the United States will be materially lower than us. It isn’t a mark of a successful economy. But neither government nor opposition have any real strategy – or interest? – in turning things around.

What do you think are our prospects of securing some big trade wins in a free trade deal with the UK or in a four-nations CANZUK deal? I think it’s quite pertinent to note that the majority of OECD nations are also EU nations, and they’ve benefitted not only from a lack of physical proximity, but considerable progress on tariff reduction through the relentless “ever closer” EU project. Our own free trade record is lackluster by comparison.

LikeLike

I can’t see a deal with the UK offering much. As I understand it, the biggest barriers to our exports relate to agricultural products and even if (unlikely) all barriers were removed, there probably isn’t much capacity here to increase production dramatically (between land/water constraints and emissions targets). UK/EU tariffs etc on manufactured goods are typically low, but there is little sign of much incipient NZ success in building businesses that penetrate those markets. Re the CANZUK ideas, I suppose the UK could seek to opt in to CPTPP (which NZ, Aus, and Can) are all part of, but similar issues arise (and even there there are barriers to entry around the Canadian dairy industry).

I don’t have a good sense of how the exports of services side is affected by non-tariff barriers etc, but there hasn’t been much sign of dramatic growth in markets where things are lightly regulated. Our exports of services performance overall (even with things totally under our control – tourism and export education) is strikingly poor.

My sense overall is that while freer trade would always be welcome, distance remains a much bigger barrier than any foreign govt restrictions on trade. And successful businesses built here are still likely to be more effective and more valuable based abroad, unless they draw primarily on some location specific natural resource. My impression is that that is also so in the bigger and richer Australia.

LikeLike

“” New Zealand’s per capita foreign trade will among the lowest in the advanced world. … It isn’t a mark of a successful economy. But neither government nor opposition have any real strategy – or interest? – in turning things around. “” Can’t argue with that.

So I will argue with idea of distance being an obstacle. We have to stop thinking in terms of physical distance and replace it with time it takes to get from place A to B. So when posting a newsletter from the local post office to members of the North Shore garden society I know it will arrive at roughly the same time as a letter to my sister in Yorkshire. It is probable that the Kiwi fruit for sale in Scotland take much the same time to arrive from orchards in NZ and orchards in Italy. To make the comparison fair the time to process customs has to be added; this is where the EU has boosted internal trade so I was surprised to see Italy on your list. A map of the world based on time to deliver would be similar to the famous London underground diagram which tends to shrink distances towards its periphery. Of course a new map is required for each trade item with our cherries being flown to Japan but their second hand cars being shipped to us [my grandfather would have been shocked that we buy Japanese second hand cars and it isn’t the other way round].

A friend used to sell aircraft parts internationally and he considered trading from NZ had a great advantage in its time zone difference – he could prepare and ship while his customer was sleeping, English being the trading language was a major advantage the disadvantages were (a) some US customers were unwilling to buy from abroad simply because they couldn’t be bothered with filling in their side of the customs declarations and (b) the exchange rate was crippling. Unfortunately the business that had traded for about a quarter century closed down just before the current drop in the NZ – US exchange rate.

LikeLike

I was hoping someone more knowledgeable would have responded with links to books and websites. As Brendon did when he introduced me to the concept of agglomeration. The word ‘distance’ is used to help explain NZ’s economic woes and opportunities. So it was satisfying to be reminded by this blogsite that if Asia is our neighbour then from the perspective of the majority of 4.5 billion Asians they have closer neighbouring islands in Sardinia and Iceland than they do in NZ. If economists and politicians have the wrong concept of distance then they are likely to produce the wrong answers to our trading opportunities.

My attempt to rephrase the question is “why do people live where they do”? Well there is a natural interia that usually swamps curiousity; why move away from family and friends and ownership? Until recently it was fairly simple: where the man can find work the rest of the family lives nearby; men’s jobs would be one of two types: dependant on location (farming, mining) or on people (teacher, cobbler, etc). Until the end of the 19th century in the UK the majority worked on the land so at least half population was spread with variations depending on soil quality. They were the basis of service jobs that before rapid transport and instant communications had to be in the proximity of the land workers.

Now very few jobs depend on location. This blogsite probably has to be in Wellington so Michael can get to various public lectures but comments arrive from all over the globe. The Auckland strawberries containing needles came from Western Australia. If I find a good book on this subject it is likely to be ordered online, printed wherever paper is cheapest and stored in an anonymous warehouse near an airport almost anywhere in the world.

So far so rather boring but consider the forces that accelerate or decelerate this change and how they apply to NZ. The move from extended family to nuclear family with both parents working is forcing more families into the cities. Language barriers slow the movement across borders so Denmark, Sweden and Finland can innovate without their innovators immediately departing for California (Lego, Nokia). National boundaries are dissolving (EU, NZ/Australia). Variations in welfare benefits are sufficient to nudge people from one country to another (I have two melanesian daughters whose allegience to boring NZ over exciting PNG grew far stronger when they had children.)

At the scale of a nation there are dramatic fast changes: try riding the Otago cycleway, parts of Northern Japan are returning to wilderness, the Canadian and American midwest is emptying, even in fast growing PNG there are valleys emptying as families move to live near the highlands highway.

If you know the “Maxwell’s demon” thought experiment replace gas molecules with people and the two containers with large Australia and small NZ; moving to Australia gives an agglomeration benefit so eventually NZ is left with a sparse number of inactive people and Australia gets all the excitement.

So according to theory the poorest English speaking country should have the largest population working overseas; it used to be Ireland and now it is NZ?

LikeLike

Bob

If it is of any interest, here is a link to a Treasury paper on distance and trade

Click to access twp14-05.pdf

and there is a whole field of economic geography (look up people like Venables), altho in my experience it is better on within-country difference than cross-country.

Why do people live where they do? Europeans came to NZ (and Aus, and Argentina, Canada etc) because it where there was affordable and productive land (not being intensively utilised by the then natives). Land (and sea) still offers good opportunities to people (directly and indirectly- related service sectors), but not 5m of them. These days of course, people move more generally because material living standards here are still better on average than those in India, China, Philippines, or South Africa.

LikeLike

Both the moving within our country and the movement between countries bother me. The ‘Maxell demon’ is the Dept of Immigration – we have a choice of who comes (carrot and stick) and to a far lesser extent who leaves (carrot only).

My point is that as technology conquers distance it also destroys local economic opportunities. For example ordering books from an American website leads to bookshops and publishers closing in NZ.

Thanks for the links, maybe economic geography will be easier than straight economics. Maybe it will explain why the blue cheese bought 10 minutes ago is from Denmark.

LikeLike

When economists argue that distance is an obstacle for us selling to overseas markets it just shows that we should have more Chartered Accountants in Treasury and in the RBNZ. Our over reliance on incorrect advice from NZ economists has resulted in the decimation of our manufacturing industries. Take note that most of the products that we have on our retail and wholesale shelves have been shipped here from all over the world from that same very long distance away and importers have been very successful, easily and cheaply getting product in from all that far away places to isolated New Zealand.

LikeLike

I’m not sure what your point is. Shipping finished products, in or out, isn’t overly expensive. But the issue I’m touching on is basing outward-oriented businesses here, where the relevance of distance is much more than just final shipping costs. NZers generate many good ideas, but if/when they work, they will often work better and more profitably from locations closer to the centres of world econ activity. The main exception is thing based on location-specific natural resources.

LikeLike

Still vividly remember one economics lecturer discoursing on economies of scale using the example of mass bread-bakeries being a product that does not lend itself to medium distance distribution because it is simply transporting 50% air bubbles.

Paradoxically, 10 years ago in Australia there was a case of Supermarkets in Tasmania selling packets of potato chips imported all the way from Holland – picture the volume of air being transported half-way around the world in those transactions

Bottles and cans of Asparagus from China and tins of fruit – mangoes and fruit etc from the Philippines are largely transporting water – yet the economics must be positive

LikeLike

“time it takes to get to a place” is a big part of the story, and of course that time hasn’t changed materially in 50 years (it still takes 24 hours to fly to London, with all the associated jet lag etc); it still takes a week or two to ship stuff to Asia (whereas it takes a couple of hours to get from Paris to London by train, and a similar time to get components from one to the other).

LikeLike

Are you arguing that it takes more time for a product or components to get from NZ to Asia/US/Europe than it is to get product and components from Asia/US/Europe to NZ? I think only economists can make that argument believable.

LikeLike

I will be travelling for holiday in Shanghai this weekend, Saturday night at 11pm. I will arrive on Sunday morning at 7.15am in the morning. This is a 12 hour flight and without the time zone I should have arrived at 11am on the Sunday but instead I am 4 hours earlier due to the time zones.

LikeLike

The big question is how and who maintains the narrative. Every morning I hear the jackass Giles Beckford(?) on RNZ singing the praises of the economy and channeling the (impartial) opinions of the banks who will always come out on top.

LikeLike

The economy grew by another 1%, jobs are stable, there is plenty of food on the table, a 65 inch LED smart TV for $2k, the friday beer and weekly dinner in a nice restaurant, the bi annual domestic holiday and that annual overseas holiday for the average Kiwi. Life is good in NZ for the average Kiwi.

LikeLike

My friends son (an engineering graduate) is getting married. They are building a house where land is affordable with a 100 km commute to work in Christchurch (50 each way). The New Zealand story is one of an economy that advantages the owners of land over everyone else.

LikeLike

I was watching the Breakfast show this morning and they were debunking the negative business confidence with an interview of a very happy Corporate Events Manager that all is good, rosy and wonderful in NZ in his business sector. Definitely the services sector is booming with 4 million tourist arrivals and the $17 billion from tourists is making its presence felt in the domestic economy.

LikeLike

I guess the problem is that our corporate heroes are now Event Planning Business entrepreneurs.

LikeLike

There is a mechanical connection between the exchange rate and the share of foreign trade in GDP, which you do not discuss.

Assume that NZ firms are price takers, with exports and imports largely priced in foreign currencies, and that the physical volume of those exports and imports is unaffected by the exchange rate (yes, I know that both of these are pretty crude assumptions). Then at a lower exchange rate the values of exports and imports are both larger in NZD terms than at a higher exchange rate, while the value of non-traded components of GDP is the same. Thus the trade share is necessarily higher when the exchange rate is lower, consistent with your historical chart. I don’t know whether this explains most of the effect, or whether there are also substantial shifts in the real proportion of trade; some analysis of elasticities would be needed to discern that.

But if a lower exchange rate increases the proportion of trade through this purely mechanical accounting effect, with little change in real economic activity, it is not clear that this would be a good thing. It would increase the profits of exporters and reduce the profits of importers and the welfare of consumers, but is that desirable in itself?

LikeLike

THanks. Yes, the direct effect was implicit (and I should have highlighted it explicitly) in those three historical episodes. Most exports and imports are priced in foreign currency so, all else equal, when the exchange rate falls sharply exports and imports as a share of GDP will rise.

If only the direct effects worked, there would be no economywide gain/loss (just a redistribution) from a change in the exchange rate. But the empirical evidence supports the view that changes in relative prices do lead to changes in real activity, and successful countries/economies (esp small ones) tend to have foreign trade growth as a significant element in that success. So my story argues that the persistently overvalued real exchange rate, relative to productivity fundamentals, has been among the things that has held us back over the last few decades. Distance would be an obstacle anyway – altho less so for 2.5m people, because of the natural resources – but the overvalued real exchange rate compounds the problem.

LikeLike

2.5m people in their 30s would be more productive than 2.5m people in their 60s as 2.5m people in their 60s need an additional 2.0m people in their 20s and 30s to care for them and to generate the 71% of the governments tax revenue that comes from GST and PAYE to fund an ever increasing 41% of government expenditure on Social Welfare and Health.

LikeLike

So five people in their sixties needs four to look after them. Something must be wrong in my household where there is one in his sixties who is assisting in various ways between three and five adults aged from 20 to 33. Short message because I have to check the stew I’m cooking for them made with ingredients I paid for so they can enjoy it in my house when they get home.

LikeLike

Don’t worry, the fact is old age happens and we all become fragile, some earlier and some later face reality. It is inevitable. But these days we do not die not like the old days when you are dead and gone by 60 anyway. You need the young ones to start to build up a tax base large enough for when the 60s in 10 short years turn 70s. It is called planning. You can’t wait until 2.5 million turn 70 and not have a pool of youngsters ready and available.

LikeLike

Michael. Do you have any comments Donald Trump versus Jacinda Aderns different views on globalisation

https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/politics/opinion/107375584/The-world-laughed-at-Donald-Trump-we-won-t-be-laughing

Do you agree with Herman Daly’s definitions

https://www.globalpolicy.org/component/content/article/162/27995.html

LikeLike

Jacinda Ardern is a Marxist Socialist(Communist) and Donald Trump is a self centered capitalist.

LikeLike

They are about as shallow and corrosive as each other (albeit in different ways), and I wouldn’t trust either of them to run a country, let alone “lead the world”. I’m a nationalist myself – and I like what I’ve seen so far of Hazony’s new book on the subject – but also a Never Trumper. I would have to concede that I really wanted the Nats out of office last year, and am not sad that happened, just a bit disappointed at how really inadequate the replacement is.

LikeLike

I ordered that on Amazon.

LikeLike