There was an article on Stuff the other day from Kirk Hope, head of Business New Zealand, suggesting (in the headline no less) that “the idea [New Zealand] is a ‘low-wage economy’ is a myth”. I didn’t even bother opening the article, so little credence have I come to give to almost anything published under Hope’s name (when there is merit is his argument, the case is almost invariably over-egged or reliant on questionable numbers). But a few people asked about it, including a resident young economics student, so I finally decided to take a look.

Hope attempts to build his argument on OECD wages data. I guess it is a reasonable place to try to start, but he doesn’t really appear to understand the data, or their limitations, including that (as the notes to the OECD tables explicitly state) the New Zealand numbers are calculated differently than those of most other countries in the tables.

The reported data are estimated full-time equivalent average annual wages, calculated thus:

This dataset contains data on average annual wages per full-time and full-year equivalent employee in the total economy. Average annual wages per full-time equivalent dependent employee are obtained by dividing the national-accounts-based total wage bill by the average number of employees in the total economy, which is then multiplied by the ratio of average usual weekly hours per full-time employee to average usually weekly hours for all employees.

That seems fine as far as it goes, subject to the limitation that in a country where people work longer hours then, all else equal, average annual wages will be higher. Personally, I’d have preferred a comparison of average hourly wage rates (which must be possible to calculate from the source data mentioned here) but the OECD don’t report that series (and I don’t really expect Hope or his staff to have derived it themselves). Although New Zealand has, by OECD standards, high hours worked per capita, we don’t have unusually high hours worked per employee (the reconciliation being that our participation rate is higher than average) so this particular point probably doesn’t materially affect cross-country comparisons.

The OECD reports the estimated average annual wages data in various forms. National currency data obviously isn’t any use for cross-country comparisons, so the focus here (and in Hope’s article) is on the data converted into USD, for which there are two series. The first is simply converted at market exchange rates, while the second is converted at estimated purchasing power parity (PPP) exchange rates. Use of PPP exchange rates – with all their inevitable imprecisions – is the standard approach to doing cross-country comparisons.

Decades ago people realised that simply doing conversions at market exchange rates could be quite misleading. One reason is that market exchange rate fluctuate quite a lot, and when a country’s exchange rate is high, any value expressed in the currency of that country when converted into (say) USD will also appear high. Take wages for example: a 20 per cent increase in the exchange rate will result in a 20 per cent increase in the USD value of New Zealand wages, but New Zealanders won’t be anything like that amount better off. The same goes for, say, GDP comparisons. That is why analysts typically focus on comparisons done using PPP exchange rates.

But not Mr Hope. Using the simple market exchange rate comparisons, he argues

OECD analysis however shows that NZ is not a low-wage economy. We sit in 16th place out of 35 countries in terms of average wages.

(Actually, I count 14th. And recall that it isn’t many decades since we were in the top 2 or 3 of these sort of league tables.)

But he does then turn to the PPP measures, without really appearing to understand PPP measures.

But the OECD analysis also shows that among those countries our relative Purchasing Power Parity (PPP), a measure of how much of a given item can be purchased by each country’s average wage, is lower.

New Zealand is included among a group of countries – Australia, Denmark, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK – where wages don’t buy as much as they could.

That’s right: Australia – where the grass has always been deemed to be greener, and Switzerland – which has long been lauded for its quality of life.

There are several possible explanations for wages in this group being higher than their PPP.

The Nordic countries have high tax rates, which support their social infrastructure but dilute their spending power.

We have lower tax rates – but the costs of housing, as an obvious example, are a lot higher in PPP terms than in other countries.

In PPP terms, the estimated average annual wages of New Zealand workers, on these OECD numbers, was 19th out of 35 countries. The OECD has expanded its membership a lot in recent decades – to bring in various emerging economies, especially in eastern Europe (the former communist ones). But of the western European and North American OECD economies (the bit of the OECD we used to mainly compare ourselves against), only Spain, Italy, and (perpetual laggard) Portugal score lower than New Zealand. On this measure.

But to revert to Hope’s analysis, he appears to think there is something wrong or anomalous about wages in PPP terms being lower than those in market exchange rate terms. But that simply isn’t so. In fact, it is what one expects for very high income and very productive countries, even when market exchange rates aren’t out of line. In highly productive economies, the costs of non-tradables tend to be high, and in very poor countries those costs tend to be low (barbers in Suva earn a lot less than those in Zurich, but do much the same job). Poor countries tend to have PPP measures of GDP or wages above those calculated at market exchange rates, and rich countries tend to have the reverse. It isn’t a commentary on policy, just a reflection of the underlying economics.

Tax rates and structures of social spending also have nothing to do with these sorts of comparisons. They might be relevant to comparisons across countries of disposable incomes, or even of consumption, but that isn’t what Hope is setting out to compare.

But he is right – inadvertently – to highlight the anomaly that in New Zealand, PPP measures are below those calculated on market exchange rates. That seems to be a reflection of two things: first, a persistently overvalued real exchange rate (a long-running theme of this blog), and second, the sense that New Zealand is a pretty high cost economy, perhaps (as some have argued) because of the limited amount of competition in many services sectors.

But there is a more serious problem with Hope’s comparisons, one that presumably he didn’t notice when he had the numbers done. I spotted this note on the OECD table.

Recommended uses and limitationsReal compensation per employee (instead of real wages) are considered for Chile, Iceland, Mexico and New Zealand.

Wages and compensation can be two quite different things. If so, the comparisons across most OECD countries won’t be a problem, but any that involve comparing Chile, Iceland, Mexico or New Zealand with any of the other OECD countries could be quite severely impaired. In many respects, using total compensation of employees seems a better basis for comparisons that whatever is labelled as “wages” – since, for example, tax structures and other legislative mandates affect the prevalence of fringe benefits – but it isn’t very meaningful to compare wages in one country with total compensation in another.

Does the difference matter? Well, I went to the OECD database and downloaded the data for total compensation of employees and total wages and salaries. In the median OECD country for which there is data for both series, compensation is about 22 per cent higher than wages and salaries. I’m not 100 per cent sure how the respective series are calculated, but those numbers didn’t really surprise me. Almost inevitably, total compensation has to be equal to or greater than wages. (There is an anomaly however in respect of the New Zealand numbers. Of those countries where compensation is used, New Zealand is the only one for which the OECD also reports wages and salaries. The data say that wages and salaries are higher than compensation – an apparently nonsensical results, which is presumably why the OECD chose to use the compensation numbers.)

So what do the numbers look like if we actually do an apples for apples comparison, using total compensation of employees data for each country. Here I’ve approximated this by scaling up the numbers for the countries where the OECD used wages data by the ratio of total compensation to total wages in each country (rather than doing the source calculations directly).

On this measure, New Zealand comes 24th in the OECD, with the usual bunch behind us – perpetual failures like Portugal and Mexico on the one hand, and the rapidly emerging former communist countries on the other. On this estimate (imprecise) Slovenia is now very slightly above New Zealand. By advanced country standards, we are now a low wage (low total employee compensation) country.

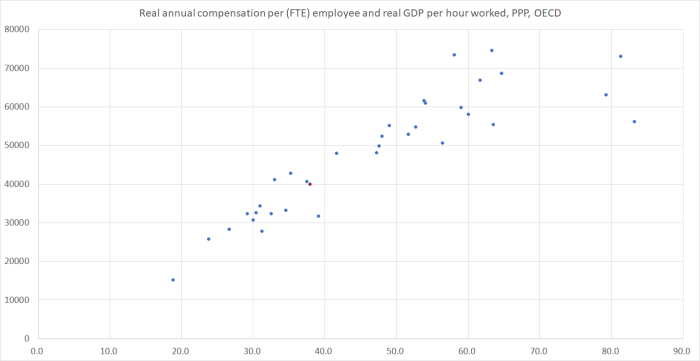

But it is about what one would expect given New Zealand low ranking productivity performance. Here is a chart showing the relationship between the derived annual compensation per (FTE) employee (as per the previous chart) and OECD data on real GDP per hour worked for 2016 (the most recent year for which there is complete data). Both are expressed in USD by PPP terms.

Frankly, it is a bit closer relationship than I expected (especially given that one variable is an annual measure and one an hourly measure). There are a few outliers to the right of the chart: Ireland (where the corporate tax rules resulted in an inflated real GDP), Luxembourg, and Norway (where the decision by the state to directly save much of the proceeds from the oil wealth probably means wages are lower than they otherwise would be). For those with sharp eyesight, I’ve marked the New Zealand observation in red: we don’t appear to be an outlier on this measure at all. Employee compensation appears to be about what one would expect given our dire long-term productivity performance.

And that appears to be the point on which – unusually – Kirk Hope and I are at one. He ends his article this way

We need to first do the hard yards on improving productivity, and then push for sustainable growth in wages.

If we don’t fix the decades-long productivity failure, we can’t expect to systematically be earning more. Sadly, there is no sign that either the government or the National Party has any serious intention of fixing that failure, or any ideas as to how it might be done.

Incidentally, this sort of analysis – suggesting that employee compensation in New Zealand is about where one might expect given overall economywide productivity – also runs directly counter to the curious argument advanced in Matthew Hooton’s Herald column the other day, in which he argued that wages were being materially held down by the presence of Working for Families. In addition, of course, were Hooton’s argument true then (all else equal) we’d should expect to see childless people and those without dependent children dropping out of the labour force (discouraged by the dismal returns to work available to those not getting the WFF top-up). And yet, for example, labour force participation rates of the elderly in New Zealand – very few of whom will be receiving WFF – are among the highest in the OECD and have been rising.

And, of course, none of this is a comment on the merits, or otherwise, of any particular wage claim.

Hi Michael

I read the Business NZ article and found it very disappointing use of data. Using data to say we are not low wage simply because there is a host of countries below us that include the former communist countries is absurd.

The other interesting comment in Business NZ’s article is that NZ is high cost. They are on the mark here but you only need to look at the OECD economic survey for NZ and the comments on large price margins and a lack of competition as the reasons why. The commerce commission is getting more teeth but it would be useful to have the productivity commission look at (the lack of) competition in a few sectors too.

regards

Cam

LikeLiked by 1 person

In the weekend I spent talking to a IT Project Manager currently based in Hong Kong. Her parents are older HK migrants who have brought up their children as kiwis who are now in their 30s and they are in their 70s. The father recently had a stroke and was hospitalised which necessitated her return from Hong Kong to care for her parents.

She has decided to return to NZ with her husband as she had been on sick/annual/emergency leave from her employer in Hong Kong now for more than 2 months and further extension was not possible. We discussed pay on her return what would be possible for her. I indicated that she should drop her expectation to around $110k to $130k as without NZ work experience NZ employers tend to tone back the salaries offered. After perhaps 6 months to a year’s NZ experience then look at moving that to $150k to $180k which was where she felt comfortable given her work experience in HK. But I did indicate that in large projects, Project Manager can earn up to $1 million if all the key performance benchmarks are met and the project delivered on time and on budget. As Fletcher has learned, NZ has one of the most complex and difficult business environments rife in legal corruption in the world contrary to what various the business surveys indicate.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Michael I thought this article on productivity from Liam Dann that analysed the latest Global Innovation Index was good. Liam’s conclusion was to speculate that countries which over invest in property seem to be the outlier bad performers wrt innovation.

https://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/news/article.cfm?c_id=3&objectid=12091676

LikeLike

It was interesting, altho I thought his conclusion was subject to the same critique I make of similar views expressed by the likes of Grant Robertson, Gareth Morgan, Bernard Hickey etc: we don’t overinvest in housing (given our population) but underinvest.

My take is more akin to the ANZ’s interesting housing piece the other day

https://www.anz.co.nz/resources/4/a/4a28ef88-3f49-4c17-99e4-9549d39e0934/ANZ-PropertyFocus-20180718.pdf?MOD=AJPERES

Crowding out To the extent that high house prices are a symptom of excess demand pressure (perhaps exacerbated by strong population growth for example), for a given level of domestic saving (which is low in New Zealand – hence our persistent current account deficits), this will tend to push up real interest rates. And all else equal, these higher interest rates will result in a higher real exchange rate than would otherwise be the case, potentially stifling exporting and import-competing activity.

There is debate surrounding the extent to which excess demand has contributed to upward pressure on the real exchange rate in New Zealand compared with other factors like our low rates of saving, the remoteness and perceived riskiness of the economy, and our shallow capital markets.6 But we suspect the exchange rate is higher than would otherwise be the case as a consequence of a combination of these factors. To the extent that excess demand pressures are at play, housing unaffordability may be impacting our broader productivity by crowding out the tradables sector through this channel.

(footnote 6 is a link to my 2013 paper on these issues)

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is rather strange that economists like Liam Dann just do not want this productivity issue fixed. There seems to be a strange obsession with spreading fake news. The focus on property being the cause of productivity problems is a clear intent to misdirect the public and the governments attention elsewhere. Usually the RBNZ and Treasury has been immature and takes the misdirection bait thrown out by banks propaganda economists.

LikeLike

Liam Dann: Dumbing down – New Zealand economy not getting smarter

https://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/news/article.cfm?c_id=3&objectid=12091676

The only dumbing down is Liam Dann’s dumb ending to his otherwise excellent article ie property investing is the cause of the NZ economy dropping down the Innovation index.

It is actually our continued government subsidies in the Primary sector and tourism that is dumbing down NZ. We have reached peak cow and it is starting to be clear that this is a sunset industry. The faster we transition out of Primary Industries the more innovation in technology based industries we would have.

LikeLike

The thing is, Business NZ represents one of the key sector interests that have the most prospect to improve productivity. So the misrepresentation of data from that particular organisation bodes very poorly for our future.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve been leafing through an old copy of Robert Wade’s ‘Governing The Market’, which is mainly about comparing the policies behind Taiwan’s growth miracle from the 1950s to the 1980s with other economies in Asia (mainly Korea), Latin America and the US. The list of things they did to increase productivity is actually depressing because there were so many we could never hope to match. To cheer myself up, I had a look through some of the OECD country reports for our new peers, Slovenia and Czech Republic. Apparently the biggest problem with the Czech economy (3-4% growth) is skills shortages, and the cure is more immigration. Perhaps we could send them some of our top economic advisers, for a fee of course.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah yes, immigration…that’s the answer. You might recall this post from a while ago when the then OECD chief economist claimed that immigration was in the process of transforming NZ productivity etc (for the better)

https://croakingcassandra.com/2017/06/15/a-true-believer-from-the-oecd/

As for the Czechs, I’m just reading at the moment “Orderly and Humane”, a scholarly account for the expulsion of ethnic Germans from Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Yuogslavia after the war – the actual process being anything but orderly or humane. One of the more harrowing books I’ve read in a while.

And of course immigration is very rarely the answer for anyone other than the immigrants……unless, of course, it is the movement of some more highly productive population groupings, moving to am underinhabited land with few peoople. Which describes 19th C NZ and Australia rather well, but might be looked at with a certain ambivalence (genuine pros and cons) by the Maori and Aboriginal populations.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Interesting; in your opinion did the German economic miracle after the war benefit from the German immigrants from Eastern Europe? Am I right in suspecting the majority had been living outside German for many generations?

LikeLike

Not sure – would be very hard to disentangle that effect from everything else going on (altho the book I’m reading has got me interested in finding a good scholarly treatment of the econ history of W Germany from 1945 to say 1970.

But bear in mind that the biggest chunk of people had been in Germany for ever, but the borders moved (Poland was moved 200kms westward, so lots of Poles moved out of the Soviet Union, and huge numbers of Germans were forced out of the newly-Polish territory. Most of the ethnic Germans in Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia will have been living in the Austro-Hungarian empire (itself ethnic German dominated) until the end of WW1

LikeLike

Not a “scholarly treatment of the econ history of W Germany from 1945 to say 1970”, but Tony Judt’s ‘Postwar. A History of Europe Since 1945’ gives a fairly comprehensive coverage of what happened in (mainly Western) Europe after 1945, and why. His other books cover aspects of the same topics.

LikeLike

Hirta island is 120 miles west of mainland Scotland. Inhabited for over 2,000 years it once had a population of 180 but that declined and it has been uninhabited since 1930. The last inhabitants moved to Glasgow. Niue is 1,500 miles from New Zealand; it had a population of 5,200 fifty years ago but currently has only 1,600 but there are over 10,000 Niueans living in Auckland. New Zealand is an Island group to the west of Australia; there are over 600,000 Kiwis living in Australia (with one in six Maori currently living in Australia). The obvious link is people on small islands dream of a better life on a bigger island where economic prospects if not better are at least more varied. Given the opportunity they move. If Australia keeps its border open does New Zealand have a future other than immigration?

LikeLiked by 1 person

My story is the other way around: if we keep on with high immigration we will keep on creating the conditions that lead so many NZers to want to go to Australia. If Australia were to close the door, and we didn’t change immigration policy, we would only make things even worse for ourselves.

My stance is that econ prospects here are fine, for a small(ish) number of people. As they are, say, in Iceland. We had about 3m people here in the 70s when things started going very badly for us. I suspect that 3m people now, and a market economy, would see living standards here materially higher than they are now. Of course, that world can’t be created, but we can stop using policy to drive us ever further away.

LikeLiked by 2 people

The difference is that the 70s had a population in their youthful mid 30s. The problem we face is that people are living longer and longer. This means that where we once had a young population we now have a old population that needs to be cared for. Comparing the 70s and today is like comparing apples with oranges. We would be severely crippled with a geriatric 3 million people these days.

LikeLike

I don’t want to make too much of either comparison, but Slovenia seems to be doing just fine (popn 2m).

Longer life is mostly a good thing. In the 70s we adopted the absurdity of state-funded retirement for everyone at 60. Now a fairly large proportion of the over-65s are still working, generally voluntarily.

LikeLike

My previous rather tongue in cheek post originally ended with the terse “Does NZ have a future”. And I was tempted to add “will the last person to leave switch off the lights”. But since clearly NZ has a growing population an explanation of how NZ is different from Niue and the isles of St Kilda was needed so I added a comment about immigration. My point being that people who can move often do so. And I suspect they do not move just for the economic benefits of agglomeration as beloved by Brendon but simply for the joy of going to the big city.

I wonder about other islands that contradict this point. Obviously Hong Kong and Singapore and New York City are not rapidly depopulating. What is happening with Ireland, Corsica, Sardinia, Cyprus, Malta, Mauritius, the Falklands, Greenland, Rhode Island, Hawaii, the Isle of Man?

For NZ to have a positive future either Australia has to stop taking Kiwis or the rest of the world our most talented Kiwis. Why would Kiwis stop leaving or at least leave us with no net emigration? Not too difficult to answer: a standard of living at least equal to wherever they can go to and then a safe happy society which is another way of saying a more egalitarian society and more controversially a strong sense of being a proud Kiwi.

That last point means a government brave enough to speak out against USA and China not just Australia; that is cautious about sending NZ troops to join foreign forces however worthy the aims. It means thinking Kiwi first and forgetting about the Kiwi having a turban or hijab or English accent. We need to work on building the sense of nationalism the Croats and Columbians displayed at the world cup and our academics and media ought to throw out multiculturalism in so far as it means building separate societies and work towards social cohesion.

LikeLike

Of course, Rhode Island isn’t an island. Ireland itself has reasonable population growth – something that changed once it sorted out its economy (back in the 70s/80d) and started generating good European incomes.

My post on small islands probably dates back to before you discovered the blog

https://croakingcassandra.com/2015/11/26/these-remote-islands-are-different/

LikeLike

Thanks for the geography lesson. Learn something new every day.

Economics is the big factor but not the only one otherwise Auckland would slow its growth.

LikeLike

50% of Slovenia exports go the European Union. I cannot see how we are even comparable with Slovenia. We do not have the EU on our door step. Living standards look equivalent to NZ currently. But you would have to pay me a ton of dollars for me to live in Slovenia. Looks like a colony of the EU. Perhaps similar to when Great Britain was the colonial empire and NZ just got rich shipping its products to the British Empire. But cut off from the rest of the world, I think that isolation means we actually need a free and open market including more immigrants that create consumption and economic activity and to care for our old.

LikeLike

I happen to agree that their location is much more propitious, but the point you were making that i was responding to was about the impact/constraints of an ageing static population.

LikeLike

Correction: 50% of Slovenia’s GDP is export GDP to the EU.

LikeLike

Main industries in Slovenia are mainly in manufacturing, ferrous metallurgy and aluminum products, lead and zinc smelting; electronics (including military electronics), trucks, automobiles, electric power equipment, wood products, textiles, chemicals, machine tools

Main exports in Slovenia are in manufactured goods, machinery and transport equipment, chemicals

Service and Primary industries are only a tiny percentage of their economy compared to our massive reliance on Service and Primary Industries.

NZ can go back to a smaller population but we would need a complete overhaul of our economy towards manufacturing. Slovenia can have a older and smaller population as its industries can easily be automated ie robots. Ours is is a peoples based service and entertainment industry which rely on having more people.

LikeLike

There is some validity to Matthew Hooton’s argument

The effect of WFF is similar to the effect of State Advances 3% loans and Capitalisation of the Child Benefit in the 1960’s and 1970’s. State Advances loans were means tested resulting in those with a few smarts who were just above the income thresh-hold to resign their employment and seek a lower paid job for 1 year to get their income down and meet the income test. The advantage of a 25 year loan at 3% exceed the drop in income. It did happen. How many people did that I have no idea. There was no evidence of un-married childless couples dropping out of the workforce

LikeLiked by 1 person