Someone around home mentioned this morning that there was a confused article on the Herald website about the progressivity (or otherwise) of the fuel tax increase. I didn’t pay much attention until I read the paper over lunch, when I was a bit staggered by what I found.

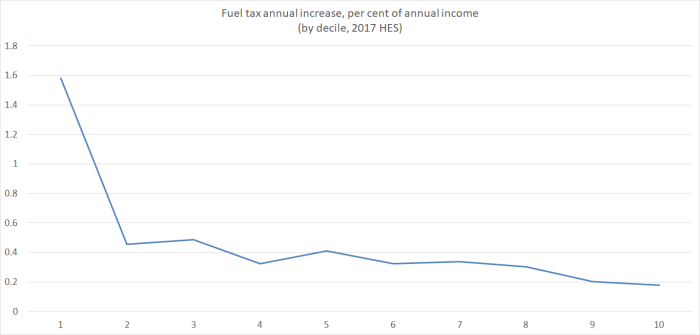

This was the centrepiece chart

The line of argument from opponents has been that the fuel tax increase will fall more heavily on low income people. But according to the Herald’s journalist, channelling Phil Twyford.

in a startling revelation, the ministers claim that the wealthier a household is, the more it is likely to pay for petrol. They say the wealthiest 10 per cent of households will pay $7.71 per week more for petrol. Those with the lowest incomes will pay $3.64 a week more.

I still don’t understand what the journalist finds startling. It is hardly surprising that higher income households spend more on petrol than lower income households do. They spend more on most things.

But he goes on to claim

This is a complete reversal of the most common complaint about fuel taxes, which is that they are “regressive”. That means, the critics say, they affect poor people more than wealthy people.

The suggestion that these data are some sort of “complete reversal” of the claim the tax is regressive is itself just nonsense. One would need to look at the impact of the fuel tax increase as a proportion of income. And households in the top decile earn about ten times as much as households in the bottom decline, according to the same Household Expenditure Survey.

So I went and got the income by decline data for the June 2017 year from the Household Expenditure Survey. The income data is presented in range form, so for each decile I used the average of the high and low incomes for that decile. And then I took the Auckland fuel tax increases numbers in the right hand column of the table above, and calculated them as a annual percentage of annual household income by decline. (The income numbers are for 2017, and the fuel tax increases phase in to 2020, so the absolute percentages will be different – incomes will have risen – but what won’t change materially is that high income households earn a lot more than low income ones.)

On the numbers the Herald themselves used, apparently supplied by the Ministry of Transport, the direct burden of the fuel tax increase will fall much more heavily on low income people than on those further up the income scale. The extremely high number for the lowest decile masks how significant these effects are even for other groups: the second and third deciles of household income will see an increase twice as large, as a percentage of income, as those in the 9th decile.

I’m driving to Auckland later this afternoon for a wedding, and planning to get out again on Sunday without having paid the increased Auckland fuel levy.

This may be the start of the usual inflation cycle under a Labour government (made worse by the stitched together coalition).

LikeLike

possibly, altho there were a lot of increases in fuel and tobacco taxes under the previous govt too. It takes excess demand, and expectations of persistently higher inflation, to get core inflation up sustainably.

LikeLike

Having returned from seven weeks overseas it seems as if prices have gone up by roughly the figures proposed by the Auckland fuel levy. Not sure whether it is international oil prices or a decline in the NZ dollar. I tend to notice when the advertised price goes past $2 either way.

A regional fuel tax is a rough solution for problems with congestion. A congestion charge would allow inhabitants to chose the times they travel and the routes they take and therefore actually reduce congestion..

It all seems rather benign; we are still recovering from the $200 (110Euro or 130 Swiss franc) taxi fare in Switzerland earlier this month.

LikeLike

The difficulty I have in this tax is that the increased income to the government / Auckland City council is not going to be used on roads, thus of a direct benefit to the petrol buyers, but on cycle ways and public transport.

LikeLike

Looks like all these taxes will go towards subsidising more biosecurity now that some silly judge with a 500 page waste of time court decision has made the government 100% liable for mistakes in biosecurity for the kiwi fruit industry.

LikeLike

Investing in public transport takes cars off the road, which opens up capacity on the road, for drivers. Surely you can understand this very very very very basic idea.

LikeLike

I guess there is an arguable case that public transport eases congestion for other road users, but certainly agree re cycleways.

I would still favour congestion charging which would both raise revenue, somewhat reduce traffic traffic demands, and send a less-crude signal to road users.

LikeLike

If public transport takes cars off the road by providing an alternative, why would this not be true for cycleways? Especially because cycleways cost basically nothing compared to roads and public transport, so the amount spent per car taken off the road is very low.

LikeLike

You may enjoy this thread: https://twitter.com/Economissive/status/1012079573733814272

LikeLike

Thanks. had i seen this material first i wouldn’t have bothered with mine.

LikeLike

Good to have multiple people saying ‘nah’. Thomas Lumley’s posted on StatsChat too: https://www.statschat.org.nz/2018/06/28/progressive-or-regressive-fuel-taxes/

LikeLike

By your own analysis, you would seem to have confirmed a previous expressed proposition of mine that, far from being relatively harmless, higher inflation, hurts people, and lower income people proportionally more than higher income people. If I understood correctly at the time, you seemed to doubt inflation was harmful at all, since its effects are in time equalized. To me inflation seems rather analogous to a regressive tax. Indeed it hurts most the very people who are likely to have less bargaining power to achieve compensating wage increases, as you demonstrate with respect to the petrol tax.

This could be seen in the context of your stated desire to boost inflation in an attempt to bolster the effectiveness of monetary policy during some hypothetical future crisis (by eventually ending up with a higher OCR). But the cure seems worse than the supposed ailment!).

And just to reiterate the point: https://www.stats.govt.nz/news/low-spending-households-continue-to-face-highest-inflation.

LikeLike

While sharing your concern about inflation I realised it is not a simple direct relationship ‘Inflation’ ‘Poverty for the poor’. I remember the 60s and 70s in the UK as being high inflation but not particularly hard for the low paid whereas my parents remembered the 30s with lower inflation and serious poverty (look at the photos of the Jarrow Hunger Marchers with their thin faces).

LikeLike

When I arrived 30 years ago in NZ, 3 bedroom houses on 800sqm in Mt Roskill cost $120k, inflation was 18% which was compensated by wages rising at 20%. I certainly did not feel poor on a $30k wage. I started work with Fletcher Challenge which was the largest company on the NZX at the time working in the IT area on those large Wang computer systems.

LikeLike

But this isn’t generalised monetary inflation, which is what I was making my earlier arguments about, but about a specific, specifically designed, tax increase. The tobacco taxes are another that falls disproportionately on poorer people.

LikeLike

How does “generalised monetary inflation” not fall disproportionately on poorer people? Tobacco taxes, petrol taxes and all forms of price increases feed into the CPI, which is the basis for the “headline” rate of inflation – isn’t this our measure of “generalised” inflation?

LikeLike

Let me come back to you on Monday when I can write on something bigger/faster than a phone screen.

LikeLike

But you are combining several quite different types of price change. Petrol and tobacco taxes are just that – tax changes – and altho they appear in the headline CPI they are no more generalisd inflation than, say, a revenue-equivalent income tax increase would be. And not all specific taxes need to be regressive – think of ones on electric cars, overseas holidays, symphony orchestra tickets, yachts or whatever.

But this exchange started with my call for an easier monetary policy to raise the general rate of inflation, and thus expectations and future nominal interest rates. There is no particular reason I can see why such an approach should lead to persistent relative price changes, favouring one income group over the other, as you appear to be suggesting. Relative price changes are real and can be very painful to specific groups, but this is a strategy where the only relative price changes are short-term moves in real interest rates (favouring econ activity today over that tomorrow, temporarily) and the real exchange rate (favouring activitiy here over that abroad, temporarily). In a simple model, pretty much all these effects will wash out over a couple of years, and we’ll be left with higher price and wage inflation, higher nominal interest rates and a lower nominal (but not real) exchange rate. Perhaps you have some more complex model in mind? But the historical CPI data alone is mostly telling you about the burden of recent tax and related changes – which prob have fallen more heavily on the poorer – and about the particular sequence of relative price changes over recent years. A different mon pol wouldn’t, as far as I can see, have prevented any of these.

LikeLike

So, finally, in conclusion, you are allowed to say – it’s regressive

LikeLike

It’s no wonder governments have the reputation for being the greatest source of poverty. Where did this man go to school?

It’s on a par with the McGilicuddy Serious Party policy of getting rid of inflation by ceasing publication of the CPI.

LikeLike

There is a fundamental problem with the official CPI in that it mis-represents the real inflation in BASIC items required for life. The real increases in food, council rates, insurances,transportation, medicines,… are higher than the official CPI. Therefore any adjustments to wages, benefits, pensions according to the CPI results only in partial compensation for the real increases in cost -of-BASIC-living.

CPI is good for political posturing and for hiding the true state of economic situation for the majority of bottom/middle class NZers.

This CPI based system reinforces the view: “Rich get richer, poor get poorer”.

LikeLike

When they stripped out land prices from the inflation index in the 1990s, wages started to get out kilter with house price increases. Prior to that even when inflation was running at 18%increases, I was getting 20% pay increases.

LikeLike

I am trying to understand your argument but seem to keep getting stuck on the basics. What is general inflation if not the multitude of individual price movements that make up the total? The point I was suggesting, which I thought was pretty uncontroversial, is that all inflation – whether emanating from tax increases, a lower exchange rate, higher markups, wage increases feeding into higher prices, or whatever else – is still going to be damaging to people’s purchasing power – everyone’s on average. And that people on lower incomes are going to be relatively less well off as a result than people on higher incomes because inflation is itself inherently regressive. Loss of purchasing power underlies the very concept of inflation. It seems to me that this one of the points behind having statistics like the household living cost indices, is so that the impact of inflationary policies isn’t lost on highly paid policy makers. I could add that “general” inflation still hurts businesses that compete internationally, because by its very nature it weakens our competitiveness relative to our trading partners – depreciating the real exchange rate with no gain to anyone. Artificially raising and then maintaining a higher inflation rate has to have ongoing consequences for out external competitiveness surely?

“In a simple model, pretty much all these effects will wash out over a couple of years…”

I think this is a key assumption with your argument, and I’m not sure the economy – which does not necessarily behave like a simple model – is so simple to manipulate, but is highly complex. Can I ask has this actually been tried anywhere or is it just theory? I would think there would be considerable consequences on large groups of real people from an ongoing artificially higher general inflation rate, and for whom the effects of higher inflation may not just “wash out” – in particular those on fixed or low incomes (many employment contracts don’t even have CPI clauses these days). And even if it did wash out within a few years – holding all else equal presumably – why should we have to go through that pain (higher prices, lower nominal exchange rate, higher nominal interest rates, potentially lower real wages and so on)? The objective of higher interest rates for the sake of some uncertain and vague benefit based upon some unknown future economic event would be difficult to sell and highly unpopular, as well as risky.

LikeLike

Err, sorry, that should be “appreciating the real exchange rate” (as competitiveness falls).

LikeLike