Yesterday the Productivity Commission hosted a seminar at which the Maxim Institute’s Julian Wood presented his ideas on regional development policy. The Maxim Institute is a policy think-tank, often seen as towards the conservative end of the spectrum, based in Auckland, and over recent months they have published a couple of papers on related issues. The second of these Taking the Right Risks: Working Together to Revitalise our Regions, was the focus of yesterday’s presentation.

(The seminar ran under Chatham House rules, which means I can’t name the person who championed the success of planning in Auckland, and lamented that we don’t yet have such a plan in Wellington.)

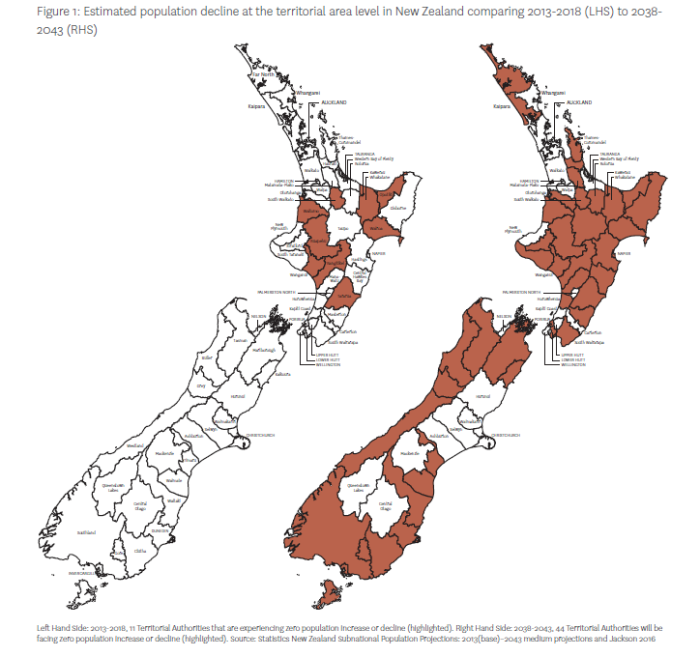

Wood – a former Department of Labour researcher and policy analyst – began his presentation with this chart from the first of the two papers.

The first panel highlights the TLAs where population has been static or is estimated to have fallen between 2013 and 2018, and the second panel is the projections in 25 years time (2038 to 2043) from the SNZ subnational population projections. On those numbers, the national population will still be growing quite a bit, but most TLAs would be seeing flat or falling populations. These numbers apparently excite a lot of interest in provincial New Zealand – or at least in the local authorities and local “economic development” agencies. There is, we are told, much gnashing of teeth.

It isn’t entirely clear why. In most cases, the places with (projected) flat or falling population 25 years hence, “flat” is more accurate a description than falling, and most of the projected falls are pretty small (eg a couple of per cent over five years). Taking the full 30 year period, from 2013 to 2043, TLAs that have currently less than 5 per cent of New Zealand’s population are expected to shrink in population over the 30 year horizon. And given that New Zealand fertility rates are now well below replacement (about 1.81 children per woman), a future of fairly flat or falling populations seems like one that New Zealanders individually are happy to contemplate. It is, after all, the situation now in much of the advanced world. There is a handful of TLAs where the population falls projected do look quite stark – eg Kawerau, Opotiki, South Waikato – and there may be some specific issues for local authorities in those area (especially dealing with central government infrastructure mandates), but it hardly looks like a case for widespread concern. And it isn’t as if isolated substantial falls in population are a new phenomenon: Taihape’s population now is about half what it was in the 1960s; Hokitika’s population is not much more than half what it was in the 1860s.

Not only is population decline not a new phenomenon – even in New Zealand – but we can, when we look abroad, see that it also isn’t inconsistent with productivity growth and improved material living standards. Most eastern and central Europe countries have flat or falling populations, and those countries are typically doing rather well economically (Japan’s population is also flat or slightly falling, and South Korea’s is rapidly getting to that point, both countries that continue to rack up productivity growth.)

It also wasn’t clear whether Wood was framing his proposed policy responses around the prospect of falling populations in some of these areas or around some perception of poor economic outcomes in some regions at present. And the two don’t seem well-aligned. Thus, if we look at the regional GDP numbers, the regional councils with the lowest average per capita GDPs are Northland and Gisborne. And yet on the SNZ projections, the population of Northland is expected to be 20 per cent higher in 2043 than it was in 2013, and the population of Gisborne is expected to be 6 per cent higher (although falling a bit by the end of the period). Whatever the issues in those two regions, population doesn’t seem set to be one of them (unless, arguably, too little outward migration to regions offering better opportunities).

But whatever the precise motivation, – and some of it simply seems to be the advent of Provincial Growth Fund and a dedicated Minister of Regional Development – Wood (and Maxim) seem keen on the potential of regional development policy (or “customised regional development pathways” harnessing “the great potential benefits of spatial policy tools”). I came away from the seminar – and from reading their paper – no more convinced than I was by the evangelical spiel offered up by a former MBIE staffer at a Treasury lecture on this stuff last year.

There was, as far as I could see, no analysis at all of what the market failures were, and why then there might be a role for active targeted measures, whether taken by central or local government. And even though one of his key themes was that locations matter, it was striking that the overwhelming bulk of the hundreds of studies he drew from were of experiences in Europe. Thus, featuring prominently in the paper was a table described as a checklist of indicators of regional growth and decline, explicitly stated as being drawn from European experience. Among the items on the “indicators of decline” were “an economic base founded on resource exploitation and/or the primary processing of this exploited resource”. Not only does that substantially describe New Zealand (and Australia) as a whole, but it also specifically describes Taranaki – the region with the highest average GDP per capita in New Zealand – and Western Australia (highest GDP per capita in Australia) and Alberta (highest GDP per capita in Canada). Marlborough – without oil or coal – had much the same average GDP per capita as Auckland last year (the sort of relative performance one doesn’t see in any EU country).

The author has been around long enough to have a certain scepticism. As he notes

Spatial policy introduces “serious risks” like “misallocating resources, creating a dependency culture and favouring rent-seekers over innovators.” Even the Minister of Regional Economic Development has outlined that the new Provincial Growth Fund is a “bloody big risk…”

But in any rational calculus, big risks require a reasonable prospect of big rewards to make the punt worthwhile. And nothing in the report suggests any real basis for confidence that such rewards are in prospect, no matter how well targeted, designed, and governed the interventions are. The author knows the pitfalls – and so he can write sensibly about the need for clear and explicit goals, for a heavy investment in evaluation, for a governance model that blends top-down and bottom-up perspectives, and also about the need to recognise that any experimentation involves allowing for the possibility of individual failures.

But as I listened to him talk, and as I read the paper later, I was still at a loss to know what he really favoured. There was enthusiastic talk of R&D tax credits – including by reference to Israel, a country with as poor a productivity performance as our own – but nothing to indicate why such a measure was particularly suited to regional development (let alone any analysis of why firms don’t find spending on R&D more attractive). There seemed to be some enthusiasm for immigration, although he knows some of the caveats there. Weirdly, the concluding paragraph of his entire “smart growth” section is all about labour supply – which seems mostly to put the cart before the horse, as people will typically be ready to move to where the opportunities are (indeed if the opportunities are in the provinces, more of their own talented young people will stay or come back). And any policy approach which includes as one of its key items – as this one does – requiring local authorities to include even more pages in their long-term planning documents (vapid enough anyway) will struggle to be taken seriously, at least outside government departments.

My own take on these issues is that people who talk about regional development – whether under the previous government or the current one – are usually looking in the wrong place. There seems to be a knee-jerk political need to “do something” and to be seen to do something, even when the action isn’t based on robust analysis specific to New Zealand (and thus the laudable call for good governance, careful targeting etc is mostly a forelorn hope, whistling in the wind). I searched both Maxim documents and was struck (if not greatly surprised) to find no reference at all to the way in which the real exchange rate – persistently high even in the face of our relative productivity decline and itself a reflection of domestic demand pressures – has reallocated resources away from the regions (generally with quite export-oriented production bases) to Wellington and (in particular) Auckland. A real exchange rate that was 30 per cent lower – and that is the sort of change implied by real interest differentials – would make a huge difference to the relative prospects of places like Hawkes Bay, Nelson, Otago, Southland, Gisborne, and so on – orders of magnitude more so than the best of the smart active initiatives Maxim seems to be calling for. (I was also struck by the fact that although there were numerous references to tax incentives and R&D tax credits, there was nothing at all about the basic rates of business taxation – if you want more of something, tax it less heavily.)

But as I look at the New Zealand data, I’m also struck by the way there isn’t an overall New Zealand regional story, and even to the extent there is, the differences between the richest parts of the country and the poorest seem no larger (and generally smaller) than those elsewhere. I had a look through the EU regional data this morning. GDP per capita in London, for example, is 150 per cent above that in regions like Durham, South Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, and West Wales. The margins are almost as large between Paris and some of the outer French regions. Margins of 100 per cent seem pretty common looking across EU countries. And what of New Zealand? Northland and Gisborne last year had average GDP per capita of almost 65 per cent of that of Auckland (and 58 per cent of that of Wellington) – ie Auckland is about 50 per cent higher than them. And as I noted above, Marlborough had much the same GDP per capita as Auckland – and there is nowhere in provincial France, UK or Germany with anything like the average GDP per capita of Paris, London, or Hamburg respectively.

Regional development policy, however cleverly designed or governed, isn’t what this country needs – arguably it never has been (and Maxim has a nice appendix on past failures). What it needs is hard-headed policy focused on lifting overall economic performance, notably productivity growth, based on a compelling and carefully scrutinised narrative that explains how we got where we are, not just grabbing bits from some generic OECD handbook, from a need to do something/anything. In practice, that approach – adopted in New Zealand for a quarter of a century now, at least – responds to symptoms not causes, and if it sometimes seems to produce benefits (albeit rarely) it is by chance rather than by the inherent merits of the policy approach. I suspect that a better-designed set of policies in New Zealand would tend to boost the regions relative to Auckland and Wellington, but that wouldn’t (and shouldn’t) be the goal: the goal should be lifting opportunities for better material living standards for all New Zealanders, and enabling New Zealanders to move to take advantage of those opportunities wherever they are to be found.

I also think the Provincial Growth Fund won’t do anything. What about building a university in Nelson, has anyone run the business case on that? We need more university towns.

LikeLike

I’m more sceptical. If anything we may have too many people going into tertiary education as it is, and no single really excellent university. Nelson Marlborough Institute of Technology (the old polytechs) seems to offer 10 bachelor’s degrees.

Also, another university would attract individual skilled staff (and some students) but I’m not sure about the evidence of spillovers. New Haven, I’m told, is a poor and dangerous place, despite hosting Yale.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Did a course on the NZ Land Act offered by the Bay of Plenty Unitech. The entire course was online. Online lectures and tutorials. Online submission of assignments and discussion and a final exam held in a hotel conference room in Auckland. Worked well so I don’t expect the government to be investing in more bricks and mortar Universities.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Questions

1. Who Funds the Maxim Institute

2. Two Graphs – what is the highlight – brown shade or white

3. What on earth was the reason for Chatham House suppression

LikeLike

Don’t know about 1 (their annual report might be online). It has been around now for almost 20 years. It used to be quite socially conservative, and probably attracted donors from those circles, but these days it seems more electic. They have, for example, the very liberal Chief Justice delivering their annual lecture in August.

The brown shade is the areas with population flat or falling.

Chatham house rules is pretty standard for such fora, and I don’t have a problem with it. Lots of public servants come to such things and (eg) they couldn’t say anything frank if someone like me could name them or their organisation. In practice, it would probably end up being non-govt people like me who no longer got invited. And the papers presented are usually readily available, as in this case.

LikeLike

The Auckland LG amalgamation, I suspect, ruined the general public view of amalgamation. A government commissioner should have been put in place in that instance to ensure that the projected/promised benefits of amalgamation were realised. Instead the opposite happened – the data provided us with a worst case, case study.

Had the Wellington region gone for amalgamation, this decision in the name of economic development would likely not have happened;

https://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/news/article.cfm?c_id=3&objectid=12070937

The real beneficiary of that subsidy is Todd Property – the airport owners.

LikeLike

I do not think in general Aucklanders have a problem with the Supercity amalgamation. Makes sense rather than trying to deal with 4 different building planning and Resource Consents rules in 4 different Councils.

The problem resides mainly in the courts making Council fully liable for building inspections which means that every Council building inspection must comply to the infinite legal detail which delays the entire building process as they try and dot the i’s and cross the t’s. Reliance on a builders professionals is not legally sufficient which creates unnecessary duplication. Blame our justice system. Perhaps it is just bad law making.

LikeLike

Seriously …… you gotta laugh

NZ population in 2000 was 3.8 million

NZ population in 2017 was 4.8 million

In 2004 NZS estimated NZ population to reach 5.0 million by 2050

In 2016 NZS estimated NZ population to reach 5.3 million by 2050

Between 2000 and 2017 NZ population increased by 1 million in 17 years

Looking at Julian Woods geographical estimates the shaded areas of the North Island will stand still while the bulk of the increase in population of 600,000 from 4.7 to 5.3 will cram into Auckland with a slight easing obtained by leakage out to Bay of Plenty and up to Whangarei. Some older peoples may leak down to the South Island. Perhaps.

Given the problems being experienced in Auckland Super City now in 2018, the implications of those maps are grim. Hope there is a Plan C and Plan D and Plan E

LikeLiked by 1 person

Best Start from this Labour government will subsidise the birthing of more babies.

“Best Start is a $60 per week payment (up to $3,120 per year) per child for babies born on or after 1 July 2018. All eligible families will receive this payment until the child turns one, regardless of their household income. Households whose income is less than $79,000 will continue to receive $60 per week until the child turns three.Those earning above $79,000 may continue to receive payments at a reduced amount. The upper threshold is $93,858 (for one child) when payments stop.”

Also add Paid Parental Leave on top of that.

Paid parental leave is extending from 18 weeks to 22 weeks from 1 July 2018 for babies born or expected to be born on or after 1 July 2018.This also means the number of keeping-in-touch hours is increasing from 40 hours to 52. Keeping-in-touch hours allow an employee, who is on parental leave, to stay connected with their employer and perform work from time to time, such as attending a team day.

LikeLike

Thank you for another enjoyable read. Well enjoyable reading your well argued skepticism until realising my family’s future is tied to NZ’s economy and then it is depressing.

About to depart from a Paris commuter belt town after 6 weeks in Europe. Everything I buy in Euro is roughly the same price in NZ$ in NZ so it is not a holiday to be repeated too often. Quite simply UK, France, Belgium, Austria and Germany have on average more wealth per person than NZ. You have written before about Auckland’s lack of comparative wealth compared similar cities in other countries; please keep repeating this message until the idea of Auckland being a ‘super city’ dies. Comparisons with Toulouse, Strasbourg, Frankfurt, Vienna, etc are just getting embarrassing.

LikeLike

I found Spanish prices much cheaper than that of Italy and France during my December holiday to pay homage to the Pope on Christmas day. The Sagrada Familia in Barcelona is a must see, although the euro16 for entry was expensive, I console myself that this massive Starwars like cathedral construction was fully funded by visiting tourists without any government assistance.

LikeLike

What I find surprising though is that the italian brands, Lotto and Fila(now Korean since 2007) sell at much cheaper prices in the Onehunga Smart Mall in Auckland than most of the other brands like Nike, Adidas or even the French brand asic.

LikeLike