On TVNZ’s Q&A programme yesterday, the Minister for Workplace Relations, Iain Lees-Galloway was interviewed.

The Minister and his government are keen to increase union membership and are putting in place further significant increases in the minimum wage.

From his interview yesterday, here is part of the Minister’s story

….all the evidence from around the world shows us that when you have more people covered by collective agreements, that helps to drive wages up. It also helps to drive productivity, and yes, we’re a government that’s focused on transforming our economy into one that’s productive, more sustainable.

It almost invites one of those Tui ads. We’ll come back to wages in a moment, but just consider for moment that claim that there is causal relationship between steps to increase union membership (and collective bargaining) and higher (economywide) productivity. It is a shame the interviewer didn’t push the Minister on the point, but his comments suggest that he really has little idea what productivity is. It is about businesses, old and new, finding new products, new markets, new ways of doing things, new ways of combining capital and labour in ways that successfully take on the world. I’m not suggesting that unions can never play a constructive role – although they can also play a destructive one. But the Minister offers no credible story for how a greater role for unions in New Zealand will make any material positive difference to the ability of firms operating in New Zealand to take on the world from here.

That is especially so because he is quite open that his goal to shift the balance in the labour market, so that a larger share of GDP flows to labour.

CORIN So the purpose of these changes is to boost union power.

IAIN Well, it’s to get a better share of the economy. We’ve talked about having an economy that’s more inclusive, where working people can actually bargain for a fair share of a prosperous economy. That’s what we’re trying to achieve.

I’m not going to debate what is “fair” here, but as a matter of arithmetic, more for one side means less for the other, unless somehow the size of the cake itself increases faster. And since firms are the ones making the investment and location decisions, it isn’t self-evidently obvious that increased union power would lead to faster rate of real GDP growth.

In support of his claims, the Minister attempted to use the example of Australia.

If you look at the wage gap between us and Australia, that has broadened over the last 30 years. Australia didn’t dismantle their collective bargaining framework in the same way that New Zealand did. That’s part of the story, but absolutely, we’re strongly of the view that people not being in a strong bargaining position has meant they haven’t been able to make the demands on the employers.

Reading that, I had hazy memories of some posts last year (eg here) drawing attention to an increase in the labour share of GDP in the last 15 years. But what about the comparison with Australia?

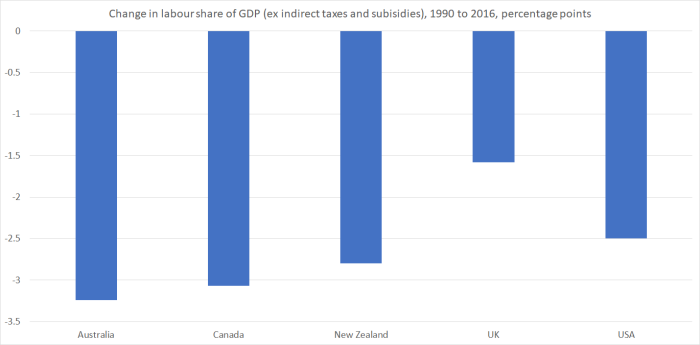

Here is the change in the labour share of GDP (less net production taxes and subsidies) since 1990. Why 1990? Well, the Minister talked about the last 30 years, but also explicitly highlighted the labour market reforms most of which date to 1991. I’ve shown the numbers not just for New Zealand and Australia, but also for the other three Anglo countries.

New Zealand is the median country. The labour share of income fell a bit less here than in Australia. If one takes the comparison just over the terms of the last two governments, so starting from 1999, the labour share of income here has increased – and in each of these other Anglo countries, it either fell or increased less than the increase in New Zealand.

I don’t want to make very much of pretty small differences. But the numbers just don’t seem to support the Minister’s case. And to revert to productivity, Australia has had one of the faster rate of productivity growth (real GDP per hour worked) among the older OECD countries since 1990. I’m not aware of any evidence suggesting that collective bargaining and the role of unions has been a material (positive) part of that story. A rather more common story is to emphasise the role of the rapid increase in Australia’s mineral exports.

The interviewer moved onto minimum wages

CORIN You talk about balance. How fair is it for a business, let’s say a business making a product that’s sold globally, with 25 staff, to now face the higher minimum wage; they lose their fire-at-will rights; they’re going to face much stronger unions, more compliance costs; they are operating in a global marketplace; they’ve lost their flexibility; how fair is it for that business?

IAIN I don’t think they’ve lost any flexibility at all. And operating in a global market means that businesses need to be resilient. They need to be able to work with the different market forces. Now, if a small change to the minimum wage is going to be that detrimental to them, they don’t sound resilient, and so what we actually need is to signal to businesses, as we have done, what our plans are for the minimum wage and for our other industrial law changes, give them an opportunity, if they don’t feel like their business model can operate in those in that environment–

CORIN So tough luck if they can’t make that work?

IAIN To give the opportunity to transition. Because we need businesses to transition into an environment where in a high-skill, high-wage economy, they are able to operate.

CORIN I think there’ll be plenty of people watching this morning who run small businesses, very frustrated and will be yelling at the TV, saying their margins are small; they’re battling away; they’re trying to employ Kiwis. They will see these changes, and certainly Business NZ is arguing that this week, as being unfair and unreasonable.

IAIN Look a lot of businesses come and go, regardless of any changes the government makes. So, yeah, most start-ups, for instance, don’t actually last beyond a couple of years. That’s the nature of doing business. What we as a government have to do is make sure there is an environment in which new businesses can develop; new jobs can be created; and as thing change for people, new opportunities become available for them. That, I think is the most important thing – that we have a strong economy where if businesses do come and go over time, which they do, that there are new opportunities for people to take up.

Now, no one is going to dispute that firms come and go, that is the nature – the desirable nature – of a market economy. But the indifference of the Minister here is all but breathtaking. His attitude appears to be that somehow we don’t want firms that can’t manage to turn a profit paying what has already been one of the highest minimum wages (relative to median wages, or to the overall productivity of the economy) anywhere.

He mightn’t, but the people who hold those jobs at present might have a rather different attitude. Sure, they’d prefer a higher wage, all else equal. Who wouldn’t? But that isn’t the scenario the Minister paints. It isn’t even the usual line the advocates of higher minimum wages run, that somehow hardly any jobs will be lost. The Minister seems to recognise that some firms will be forced out of business, and he just doesn’t care. Because amid all the blather about “new opportunities” and the earlier rhetoric about “transforming our economy into one that’s productive”, there is nothing in what the Minister is saying – or what his leaders and colleagues have been saying – to give anyone any confidence that government policy is about to transform our underwhelming productivity performance.

It is true, of course, that there might be some small measurement effects from big increases in the minimum wage. If some people are priced out of work altogether they will tend, on average, to be the least productive workers. Average productivity of those who remain may be a little higher as a result. But that is no comfort to anyone, and doesn’t earn New Zealand as a whole better opportunities in the wider world. In some cases, firms may even respond to higher minimum wages by mechanising more, but again that isn’t a gain for New Zealanders as a whole – but rather a second-best response (not the production process they’d have preferred, and which market opportunities would have warranted) to a direct government intervention. Pricing some people out of the labour market is no way to improve opportunities (and incomes) for all.

It is also not as if the increases in minimum wages are small. The minimum wage was set at $15.75 last April, and under coalition agreement it is to reach $20 per hour in April 2021. That is a 27 per cent increase in four years. There will be some inflation over that period. But on the Reserve Bank’s forecasts the other day, that will total only 6.7 per cent over four years. In real terms, minimum wages are rising by 19 per cent in only four years.

All of which might be fine if there was productivity growth to match. Over the last five years there has been only about 1.5 per cent productivity growth in total.

Perhaps the next few years will be different? But there is nothing in the Minister’s remarks offering any sort of credible explanation as to how, or why we should expect something better? Most likely, some firms – not very resilient, in the Minister’s terms – will be forced to close, to downsize, or to adopt production patterns that are less efficient than market opportunities and market prices would lead them to prefer.

Those losses are more likely to be concentrated in the outward-facing tradables sectors of the economy. Domestically-oriented firms don’t have unlimited pricing power, but they often have some – especially when across the board regulatory changes like this are put in place. Most outward-oriented firms – whether in tourism, export education, farming or wherever – have very little, if any.

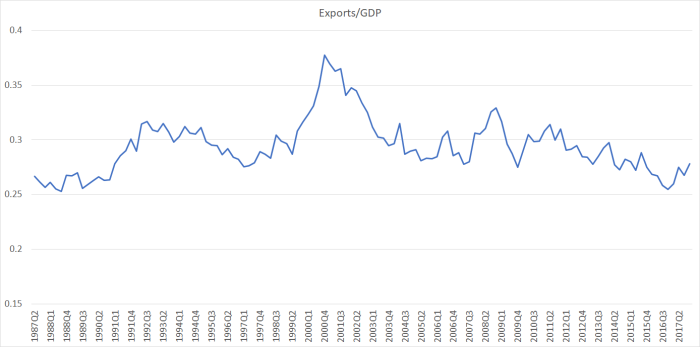

And it is not as if the economy has been successfully becoming more outward-oriented over recent years either, even before this latest scheduled lift in the real (unit labour cost) exchange rate.

One mark of a successful economy tends to be an increasing share of the economy accounted for by exports and imports – local products and services successfully taking on the world, enabling locals to consume the best the world has to offer.

Perhaps the Minister wishes for a world of abundant home-grown high-performing, high margin businesses. It might even be a worthy aspiration, but wishing doesn’t make it so, and there is no sign that government has any credible story as to what might make it so.

Changing tack, as I noted in my post on Saturday, I did an interview with Wallace Chapman for yesterday’s Sunday Morning programme on Radio New Zealand. Later in the same programme, Chapman had an interview on population issues with Massey university sociologist Paul Spoonley (he runs the government-funded immigration advocacy research programme CADDANZ) and with environmental economist Suzi Kerr, of Motu and Victoria University.

It was a slightly unnerving discussion, at least to anyone who counts children as a blessing. Kerr seemed set on encouraging people to have fewer children for the “sake of planet” (observing that she and all the people she worked with had chosen to have two or fewer), observing that adjustment to climate change would be easier with fewer people. In the course of the discussion, she was careful to disavow any particular expertise in immigration – and didn’t come across as a particular immigration booster (countering Spoonley’s arguments in a couple of placs) – but never once did she suggest that if we were concerned about reducing the number of people here that immigration policy – affecting non-New Zealanders – would be an obvious place to start. Non-citizen immigration is, after all, an increasingly large share of New Zealand’s population increase, and the total fertility rate here is already below replacement, reaching a record low last year. I suspect she isn’t much interested in New Zealand specifically and is more interested in “saving the planet”, including talking of redistributing people round the world. It was a little disconcerting given that she has just been appointed as a member of the government’s new Climate Change Commission (a fact Radio New Zealand failed to point out in introducing her). One hopes that in her new official role she will think rather harder about the easier options – if not ones necessary welcome to the political masters to whom the owes her appointment – open to New Zealand to ease the cost of adjustment to the government’s carbon targets.

As for Spoonley, he asserted – of my comments on immigration (lack of NZ specific evidence of benefits) in the earlier interview – that I was partly right and partly wrong. If he remains convinced of the economic benefits of immigration to New Zealanders as a whole, perhaps he could engage with some of the indicators I’ve referred to in various recent posts (eg here and here) – the underperforming Auckland labour market, the outflow from Auckland of New Zealanders, the way in which the margin by which real GDP per capita in Auckland exceeds that in the rest of the country is small and shrinking, all in an economy with an underwhelming overall productivity performance, and a shrinking share of the outward-oriented sectors. Spoonley’s apparent preference – to encourage/incentivise immigrants to move to places other than Auckland – is no (economic) solution either, just transferring the problems to even less productive places.

On RNZ 101.4 this morning. Japan’s idea of productivity in the psychiatric ward is to have a ratio of 1 nurse to 48 patients. To keep order, patients are tied securely to their beds and tranquilized allowing no movements. When patients die, coronary investigations are left at the discretion of the hospital which usually results in no investigation necessary. I guess this is the future that NZ envisage for its health system.

LikeLike

My old father in-law is working class Japanese. I can’t help feeling proud of him he is 80 but he dutifully and cheerfully heads off to his volunteer work where he spoon feeds [someone].

LikeLike

and on the other hand they could look at how New Zealanders have been routed. There is no reason why they couldn’t get guest workers.

LikeLike

Rather difficult to plan with old guest workers eh. One day they show up and perhaps the next day too sick to show.

LikeLike

Suzi Kerr”s view seem to mirror a discussion on the Canadian Greens website where they argued that immigration is “population neutral”. She said “we may have to move people around”. This implies that an elite expect to be in control. They can only do that if they control the media. Kim Hill would never let tem away with it [sarcasm]. I agree with her on smaller families but not your average Anglo-Saxon.

As Borrie said in 1965:

“to a demographer these Islands represent populations, however idyllic they appear to be at the moment, nearer the brink of overpopulation in the Malthusian sense than almost any other groups of peoples”

and as Kenneth Cumberland said:

Only in this century has the world’s population attained an average annual rate of growth in excess of one per cent. In mid-century it has climbed to about 1.6 per cent per annum. But in Polynesia growth rates exceed three per cent per annum; in some territories they have exceeded four per cent per annum. Projections have been made of future rates of population growth in the next two quinquennia for all the territories under review. 1 Excepting only French Polynesia, all groups have predicted future growth rates which exceed the recorded rates of growth in the last quinquennium. They range from 3.20 per cent to 3.60 per cent per annum (but in the case of the Indian sector of the population of Fiji they reach 4.25 and 4.20 per cent per annum) for the five-year periods 1962-66 and 1967-71 respectively. These last figures approach the theoretical physiological maximum.

More Recently Spoonley says:

Hau’ofa (1993) reminds us that Pacific peoples have been involved in the networks and linkages that define transnational communities for some considerable time, from “homes abroad”.

…so much of the welfare of ordinary people of Oceania depends on informal movement along ancient routes drawn in bloodlines invisible to the enforcers of the laws of confinement and regulated mobility… [Pacific peoples] are once again enlarging their world, establishing new resource bases and expanding networks for circulation (Hau’ofa, 1993:11).

He says nations are becoming less important.

LikeLike

Fake

quote:

“Australia didn’t dismantle their collective bargaining framework in the same way that NZ did”

endquote

No – but they have casualised the workforce and contractors who have no collective power

Australian Unions- Why is their membership declining? Casuals and Freeloaders

http://www.holdingpattern.info/australian-unions-why-is-their-membership-declining-what-does-it-mean-for-the-alp/

25% of the Australian workforce are not full-time employees

LikeLike

Reblogged this on The Inquiring Mind and commented:

Mr Reddell looks at the Q&A interview with Lees-Galloway and makes a number of very relevant observations.

LikeLike

“Breathtaking Indifference” seems a tad strong. I’m sure Mr Lees-Galloway is only expressing common opinions among Labour politicians. Each and every economic decision the government makes will lead to winners and losers. Their utilitarian calculus judges the benefits to those who get govt mandated pay rises exceeds negative effects on those who lose their jobs and whatever negative impact it has on the economy.

The Reddell -v- Spoonley differences about current non-citizen immigration is like two boxers in two different rings. Since I have read this blog I find the Reddell economic arguments persuasive and the counter arguments lacking factual support. However should we expect a sociologist to make economic arguments? I’m not sure if there is a Spoonley ‘social cohesion’ blog but it would be interesting to see an experts view of the non-economic benefits of immigration especially what factors are involved – I can guess language but what about religion and cultural practises – how are such attributes measured and what social costs/benefits do they involve? A related issue is what criteria is used to judge a social benefit? The economist has the advantage that we all understand money but one person’s cultural benefit is another person’s cultural poison.

[My one interaction with prof Spoonley was a very unproductive argument where I argued that diversity benefits must decline as numbers increase – for example does NZ get any diversity dividend from another POM like myself – so logically NZ should impose quotas by ethnic group or at least nationality if we want to control numbers.]

But both Reddell and Spoonley make the same mistake in treating immigrants as identical particles. So both the NZ economic and social benefits of say Shamubeel Eaqub and Eric Crampton are not distinguished from the checkout operator and the cleaner in my local supermarket. Economists and Sociologists may argue that like a physicist measuring temperature in a gas they have to work with averages however there is a difference, a physicist usually cannot separate the hot from the cold molecules but our department of Immigration has all the controls to decide who is come in. Just like an osmotic barrier. Could an economist and an sociologist work together to identify the attributes of an ideal immigrant?

LikeLike

Re Spoonley, I guess he purports to outline economic gains.

LikeLike

I get the impression the ‘all immigration is good for the economy’ argument is being used less often and it is being challenged occasionally. But it was always such a stupid argument. I think there are signs you are beginning to win. However the same self-interested parties still influence our political parties – ref your previous post.

Prof Spoonley was pushing the economic argument to U3A recently – ‘we elderly Aucklanders should be grateful Asians have made us wealthy by bidding up our house prices’. To be fair that is a more direct argument than the sophistication required to make the argument about subtle benefits of a multi-cultural society.

LikeLike

His arguments on productivity are weak. He cherry picks individual firms and extrapolates to the whole economy.

Wallace

and you think immigration is a gain for productivity

Spoonley

Absolutely. And when you can look at particular industries and particular firms in Auckland then there is (I think) evidence that immigration contributes to the productivity and innovation of those perticular firms and industries.

What does Mare say about it Michael?

LikeLike

In some ways, what concerns me more is his championing of encouraging migrants out to the provinces, which is just a recipe for even lower productivity on average. And his citation of Japan – with flat or falling population – as an economic problem, which Japan’s productivity growth rate has been perfectly respectable..

From the comments you refer to, he seemed to be conflating a number of papers. There is one suggestion an association between innovative firms and migrants – but even Spoonley was careful to use the word “association” as the authors of the paper are clear that they are not identifying a causal relationship.

Dave Mare has done various papers. One suggested any adverse effects on wages were pretty small (on its own terms, that isn’t an economywide argument i have much trouble with) and another used micro data to find higher average productivity of employees in Akld. On the latter, again I don’t find that troubling, and the study did not attempt to look at whether productivity growth in Akld is faster than that in the rest of the country. The regional GDP per capita data (annual since 2000) I’ve been citing in recent years would suggest not.

LikeLike

Wallace

Our economy is reliant on future generations, is in not? We need children to keep the tax intake going to support things we take for granted like education , health and support, so is that a factor as well?

Suzi

People talk about that a lot and I think that while that may be true, in what we have done historically, it shouldn’t be true. And people should, through their lives, now that we’re not getting massively richer as a country, we’re not a developing country anymore, we should on average be generating enough income to support ourselve across those lives. And so a combination of public and private saving, private and public superanuation schemes, should mean that we actually have enough money and enough money not only to cover superanuation but also early childhood education and health later on in life. There’s a question of transition to that balance but in the long run we should be able to do that and the question is who is actually going to be around to care for all of us when we are old and we need health workers and we need people to visit us so we are not lonely and all of those sort of actions that it’s not just a questionof money, they need to have people around.

Spoonley

Can I add to that a little bit though. I do think there’s a question of where we get our working population, so the numbers of our prime working age population are going to decline with declining fertility and at the moment it appears we’re supplementing those with immigration, but is that a sustainable long term possibility and I think we need to really have a discussion about that. So the question is are we going to have enough workers. If you look around the world, particularly at countries like germany and Japan which is the most advanced aging societies we’ve seen, so Japan’s just seen an absolute decline in it’s population and we’re going to face that. We are probably 30 perhaps 20 years behind those countries. But over the medium and long term, we do need to ask the question, where do we get people from to operate, not just what Suzi said, it’s what I call “whose going to wipe my chin?” syndrome worked in our firm our and in our labour market

Suzi

Can I come back on that one. There’s not a fixed number of jobs outside of a wipe your chine sort of space that we have to have and potentially we could have a smaller economy and be using resources we have saved in the past and getting resources from there (from saving) . Think about this on an individual basis, you don’t have to keep earning money all your life . As a country we potentially have the same sort of issue, we don’t have to have a tax base that’s the same size that it is today .

Wallace What do they do in Japan Paul. I hear there are robots that

Spoonley

we are struggling to see what that new model (how you pay for services) would look like and I’m afraid you wouldn’t look to japan as an example. 43 of their cities are now in population decline, they have enourmous skill shortages, they are short of 600,000 workers in IT at the moment in Japan and ofcourse they don’t do migration. So we probably need to look elsewhere . There’s not a good example of that new model of what Suzi’s talking about.

Wallace

That is extraordinary, could the same scenario happen in NZ

Spoonley

Yes it could, we need to be a little carefulabout this because our population is growing (as you said at the very outset), but we do immigration so immigration supplements our population but it also is an important source of our skill supply . But you’ve got to say if immigration is the answer then your asking the wrong question and I do feel worried about some of our industries which are very reliant on immigration and we need to think about how we organise ourselves, how we organise the people that work for us and as Suzi said we need to think quite radically about how we produce those services for society, but that’s a very different model from the one we have at the moment.

————-

If Japan needs 600,000 IT people you would think they could pay enough Indians to come and work on temporary visas. Spoonley uses IT as an example of why we need migrants . In A Slice of Heaven it is a key point in their case. He conflates move to NZ migration with temporary migration (eg people from Vanuatu come for Kiwifruit picking)? Yesterday on Politics with Steven M? and Mathew Hooten, Katherine Ryan switched from migrants and Auckland to migrant fruit pickers in the same breath.

He is adamant that the Japanese way is a model that we should not follow, however, obviously that is the Japanese favoured path. So what if their population falls to a reasonable level? At 120 million they aren’t in danger of dying out in a hurry. And do they really need “cultural deepening” ?

LikeLike

the last paragraph (Spoonley) is unfathomable. Can someone translate?

LikeLike

Phil Goff after having spent time in the Auckland Hospital has excluded migrants from causing this housing crises.

“Those hospitals would close down tomorrow [without] the doctors, the nurses, the staff, the ancillary staff, probably 60-70 percent of them are migrants.”

He said the same is true of other areas of the economy.

LikeLike

We wouldn’t have had all this migration without the Phill Goughs of the Labour Party. Even Spoonley admits Auckland has problems. Increased population = greater need for doctors and nurses. Kiwis can do that (they always did in the past – in fact once you went into hospital they would keep you in for weeks).

LikeLike

Sorethumb, you can’t use yesterday model for today because yesterdays model is when the baby boomers were young. Now the baby boomers are old. Old age is quite a different model to deal with. Are you suggesting that we adopt your Japanese Spouse model of 48 patients to be cared by 1 nurse and tie up old folk with dementia and tranquilize them until they die from blood clotting due to no movement in bed? The faster they die the better?

LikeLike

So, what is the right way to go about increasing the labour share of the economic pie? I can see plenty of reasons why bringing back mid-20th century style unions won’t work, but what would work better?

LikeLike

I’m not convinced it is a particularly sensible policy goal. After all, an economic strategy that greatly lifted productivity might also involve a great deal more physical investment (eg aus mining). Everyone could be a lot better off and yet a lower labour share might also be a sensible outcome. I’d focus on productivity and take ( pre tax and benefits) distribution that comes.

LikeLike

Redivert subsidising Primary Industries including tourism towards manufacturing high end leading edge products or even maintaining a chocolate factory would be more productive than a billion dollar rural road so that Fonterra can drive their trucks and pick up heavily subsidised milk products.

LikeLike

A focus on increasing productivity is fine – but where is the evidence that the rewards of such an increase will be evenly distributed and not captured by an influential few. This surely seems to have been the case in many countries where collective agreements have been in decline – or have been sidestepped by moving overseas to employ labour

LikeLiked by 1 person

There is quite a collection of high productivity countries, with very different labour market institutions (eg US and Belgium, Denmark, Netherlands, Ireland). In all of them the median employee is far better off than the NZ counterpart. I don’t have an in-principle objection to collective bargaining, but just don’t see a credible story of a causal link from collective bargaining to higher productivity.

In terms of final distributions, of course the tax and benefit systems have a role to play.

LikeLike

In effect, distributions via the tax and benefit system amount to a subsidy for business. Is that a good thing in the long run?

LikeLike

I’m agnostic on whether, on to what extent, such redistributions work that way. In principle they shouldn’t – provided there is a competitive labour market, employers will pay up to marginal product, because employees can go somewhere else. Perhaps in practice it is different. If there were a material subsidy element, it would be undesirable.

Is it worth remembering that in the era of high wages (relative to productivity) we didn’t hear this talk (eg in the 50s and 60s family benefit was universal, the income tax system was more progressive, and most first home buyers used concessional state advances mortgages, so there was lots of redistribution going on)?

LikeLike

faffinz, tax is a cost to a business and definitely not a subsidy. Tax distribution is the price of peace ie social welfare paid to the poor so that they don’t revolt and hang the rich.

LikeLike

As long as the government is heavily subsidising Primary industries including the tourism industry then productivity is a pipedream. It is better if our billion dollar subsidies go towards companies like Rocket Lab which recently became a US company due to the lack of depth of our capital markets. They still manufacture in NZ but now US owned. Rather a dumb misapplication of subsidies.

LikeLike