That was the title of a speech David Parker gave a couple of weeks ago. Parker is, as you will recall, a man wearing many hats: Minister for the Environment, Associate Minister of Finance, Minister for Trade and Export Growth, and Attorney-General. Since he was speaking to a seminar organised by the Resource Management Law Association, this speech looked like it might touch on all his areas of portfolio responsibility.

In passing, I’ll note that he clearly doesn’t live in Wellington. He introduces his speech lamenting that New Zealand had just had its hottest summer on record. Most Wellingtonians – no matter how liberal (indeed, I recently heard an academic working on climate issues make exactly this point) – revelled in a summer that for once felt almost like those the rest of New Zealand normally enjoys. The sea water was even enjoyably swimmable not just bracing or “refreshing”.

But the focus of his speech is on economic growth.

First he highlights some of New Zealand’s underperformance.

New Zealand has enjoyed relatively strong nominal economic growth over recent years, bolstered by strong commodity prices, population growth and tourism. More inputs, mostly people, have been added into the economy but, with population growth stripped out, per capita growth has been poor at about 1 per cent per annum.

That underperformance has been the story of decades now. And poor as the growth in per capita real GDP has been, productivity growth – real GDP per hour worked – has been worse. In one particular bad period, over the last five years or so, labour productivity growth has been close to zero (around 0.2-0.3 per cent per annum on average).

Parker is obviously aware of this, beginning his next paragraph “we also have a productivity problem”, but seems more than a little confused about the nature of the issue.

Capital has been misallocated, including into speculative asset classes such as rental housing, rather than into growing our points of comparative advantage.

But…….your government (rightly) keeps telling us that too few houses have been built, laments increases in rents etc. If we are going to have anything like the rate of population growth we’ve run over recent decades (let alone the last few years) ideally more real resources would be devoted to house-building, not less. Simply changing the ownership of existing houses doesn’t divert real resources from anything else, or even use material amount of real resources.

The Minister goes on

We aim to diversify our exports and markets as we move from volume to value. We want to change investment signals so more capital goes towards the productive economy rather than unproductive speculation. Where we need immigration, it will be more targeted.

That last sentence sounds promising, even tantalising. But it doesn’t seem consistent with the Prime Minister’s rhetoric, with Labour Party policy on immigration, or with the (in)action of the government on immigration policy to date. Our large-scale non-citizen immigration programme runs on unchanged, complemented by the big increases in recent years in the numbers here on short-term work visas. A reduced rate of population growth would reduce the extent to which real resources needed to be devoted to meet the – real and legitimate – needs of a fast-growing population.

The Minister also makes a bold claim

I am an experienced CEO and company director. I know from experience that we can achieve economic, export and productivity growth within environmental limits.

No doubt, as absolute statements, those claims are true. But surely the relevant question is “how much?” After all, the message Labour and the Greens were running in the election campaign was that what apparent economic success there had been in recent years was built on “raping and pillaging” the environment – water pollution, offshore oil exploration, emissions etc. And yet, as the Minister notes, even that “economic success” didn’t add up to much: weak per capita GDP growth, almost non-existent productivity growth, no progress in closing the gaps to the rest of the advanced world. And what of exports?

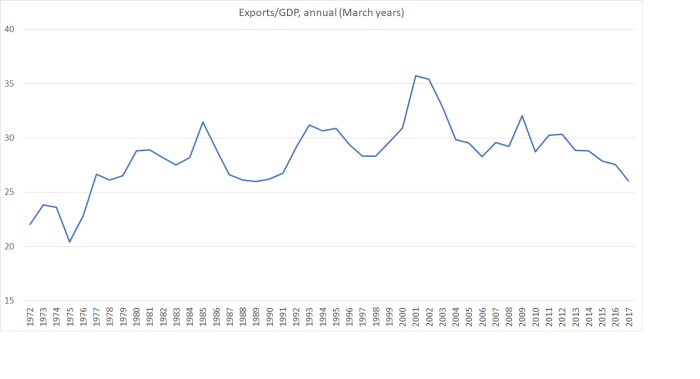

The past 15 years have been pretty dreadful, and the last time the export share of the economy was less than it was in the March 2017 year was the year to March 1976 – back in the days when (a) export prices had plummeted, and (b) the economy was ensnared in import protection, artifically reducing both exports and imports (our openness to the world more generally).

The past 15 years have been pretty dreadful, and the last time the export share of the economy was less than it was in the March 2017 year was the year to March 1976 – back in the days when (a) export prices had plummeted, and (b) the economy was ensnared in import protection, artifically reducing both exports and imports (our openness to the world more generally).

In the Minister’s own words

But economic management over recent years has put pressure on our social wellbeing and our environment.

So how, we might wonder, is a greater emphasis on environmental protection going to be consistent with the economic growth, and the exports and productivity growth that David Parker says the government aspires to?

As Minister for Economic Development and for Trade and Export Growth, my priorities reflect the reality that our economic success will be underpinned by a more productive, sustainable, competitive and internationally-connected New Zealand.

It is great to see growth in the value of output from our productive sectors. The Government wants to work with them to ensure that the right conditions are in place for firms to thrive and trade, and that we maximise the value of the goods we produce, and encourage high-quality investment in New Zealand. We want our sectors and regions to realise their full potential.

Economic growth and trade helps us create a greater number of sustainable jobs with higher wages and an improved standard of living for all New Zealanders.

However, the Government is clear that economic growth cannot continue to be at the cost of the environment. This is not idealism: it is grounded in common sense. Protecting our environment safeguards our economy in the long term – our country has built its economy and reputation on our natural capital.

I’m not arguing against improving environmental standards, perhaps especially around fresh water. Improvements in the environment are typically seen as a normal good: as we get richer we want (and typically get) more of it. But those gains usually come at some (direct) economic cost. Major change isn’t just wished into existence.

In some places, perhaps, these changes are easier than in others. If the tradables sector of your economy is, in any case, in a transition away from heavy industry to, say, financial or business services (perhaps the UK experience), you are naturally moving from industries that might otherwise tend to pollute heavily towards those that don’t. And farming – and land-based industries – might be a small part of the economy anyway.

But this is New Zealand. And in New Zealand probably 85 per cent of all our exports are natural-resource based, and total services exports (even including tourism) are no higher as a share of GDP than they were 15 or 20 year ago. Not very many new industries seem to find it economic to both develop here, and then remain here. We – and the Minister – might wish it were otherwise, but up to now it hasn’t been. Instead, what export growth we’ve had has been in industries where the government is often – and perhaps rightly – concerned about the environmental side-effects.

In his speech, the Minister declares that as Minister for the Environment improving the quality of freshwater is his “number one priority”. I might have hoped that fixing the urban planning laws was at least up there, but lets grant him his priority for now. How does he envisage bringing about change?

In environmental matters there are only three ways to change the future – education, regulation and price. Of these the most important for water is regulation

And regulation comes at a cost, reducing the competitiveness of firms and industries that are no longer free to do as they previously did. The best presumption then has to be that future growth in affected sectors will be less than previously, and less than it would otherwise have been. Sometimes, regulatory and tax initiatives spark brilliant new technologies enabling industries to move to a whole new level. But you can’t count on that. You have to work on the assumption that regulation costs. Those costs might be worth bearing, but you shouldn’t pretend they aren’t there.

The same will, presumably, go for including agriculture in the emissions trading system, however gradually. Relative to the past, firms facing such a price will no longer be as competitive as they otherwise would have been. And experts tell us that as yet there are few technologies for effectively reducing animal emissions – other than having fewer animals.

And then, of course, there are the direct bans. The ban on new offshore oil exploration permits hadn’t been announced when the Minister gave his speech, but it will – by explicit design – reduce output in the exploration sector and, over time, in the domestic production of oil and gas. It might be – as some of the government’s acolytes argue – “the thing to do”, “leading the way”, “this generation’s nuclear-free moment” [that one really doesn’t persuade if you thought the Lange government’s gesture was a mistake too], but it must come at an economic cost to New Zealanders. An economy totally reliant on the ability to skilfully exploit its natural resources, consciously and deliberately chooses to leave some chunk of those – size unknown – untapped.

Again, over the course of the last 45 years – the period of that exports chart – we’ve had a lot of oil and gas development. All else equal, our economic performance can only be set back without it – not perhaps this year, or next, but over time. And it all adds up.

Reading through to the end of the Minister’s speech there is simply no credible story for how he, or the government, expects to be able to do all these things and still see some transformation in the outlook for per capita GDP growth, or growth in productivity or exports. Indeed, there is nothing there to explain why the outlook won’t be worsened by the sorts of initiatives – each perhaps worthwhile in their own terms.

It might be different if the government was willing to do something serious about immigration policy, rather than just carrying on with the bipartisan “big New Zealand” strategy. When natural resources are a crucial part of your economy – and everyone accepts they still are in New Zealand – then adding ever more people, by policy initiative, to a fixed quantity of natural resource is a straightforward recipe for depleting the stock of resources per capita, and thus spreading ever more thinly the income that flows from those natural resources.

It is pretty basic stuff: Norway wouldn’t be so much richer per capita than the UK – both producing oil and gas from the North Sea – if Norway had 65 million people. And if Norway decided to get out of the oil and gas business – leaving underground a big part of their natural resource endowment – they’d be crazy to drive up their population anyway. But that is exactly the thrust of what the New Zealand government is doing between:

- what is aspires to do on water,

- its ambitious emissions targets, in a country with very high marginal abatement costs, and

- the ban on new oil and gas exploration permits

even as it keeps on targeting more non-citizen migrants (per capita) than almost any other country on the planet, and as the export share of GDP has been under downward pressure anyway.

It is not as if there is a compelling alternative in which export industries based on other than natural resources are thriving, boosted immensely by the infusion of top-end global talent, in ways that might make us think that natural resource industries could easily be dispensed with and a rapidly rising population was putting us on a path to a more prosperoous, productive, and environmentally-friendly future. Its been a dream, or an aspiration, of some for decades. But there is barely a shred of evidence of anything like that happening in this most remote of locations.

It might all be a lot different if the government was willing to step aside from the “big New Zealand” mentality, or put aside for a moment fears of absurd comparisons with Donald Trump – recall that (a) our immigration is almost all legal, and (b) residence approvals here (per capita) are three times those in the US (under Clinton/Bush/Obama).

If the government were to move to phase in a residence approvals target of 10000 to 15000 per annum (the per capita rate in the US), with supporting changes to work visa policies, we’d pretty quickly see quite a different – and better – economic climate. We’d no longer have to devote so much resource (labour) to simply building to support a growing population – houses, roads [rail if you must], schools, shops, offices. All else equal our interest rates – typically the highest in the advanced world – would be quite a bit lower, and the real exchange rate could be expected to fall a long way. I don’t think there is a mention in the whole of David Parker’s speech of the real exchange rate, but it is a key element in coping successfully with the sorts of transitions the Minister says he aspires to. Farmers, for example, will be able to compete, even with tougher water regulations, even with the inclusion of agriculture in the ETS. And more industries in other sector will find it remunerative to develop here, and remain based here. We’d actually have a chance of meeting both environmental and economic objectives instead of – as the government would see it – having consistently failed on both counts.

Last year, I ran several posts (including this column) making the point that rapid population growth – mostly the consequence of immigration policy – was the single biggest factor behind the continued growth in, and high level of, carbon emissions in New Zealand over recent decades. In other words, we had made a rod for our own back and then – through the process of driving up the real exchange rate – made it even more difficult and costly to abate those emissions without materially undermining our standard of living. OIA requests established that neither MBIE nor the Ministry for the Environment had even explored the issue.

It wasn’t a popular view, but I stand by the argument. In a country still very heavily dependent on natural resources, if you care about the environment, and about “doing our bit” on carbon emissions, it is simply crazy to keep on actively driving up the population. Doubly so, if you think you can do so and still improve productivity, export growth, and overall economic performance. The Productivity Commission is due to release soon its draft report on making the transition to a low emissions economy. I hope they have been willing to recognise, and explicitly address, the integral connection to immigration policy in the specific circumstances New Zealand faces. Not wishing to confront the connection – an awkward one for the pro-immigration people on the left in particular – won’t make it go away.

Michael – in your experience in the civil service did you ever see advice or analysis presented to ministers in such clear and matter of fact terms regarding a countervailing opinion to the accepted orthodoxy as what you present in this column and others?

It seems to me to be so glaringly obvious that we have created a “rod for our own back” as you describe it that any policy analyst a year out of university should be able to work it out.

If that was indeed the case would it not be reasonable to expect analysis that informs counterfactual views to prevailing orthodoxy is presented to ministers to consider relatively regularly?

Or is it in general simply a case of “yes minister” and hence why nothing much seems to change and our poor performance remains.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I guess “accepted orthodoxy” is hard for bastions of the establishment to break free of, or even see a problem with. And any individual civil servant isn’t just an individual, but part of an entire organisation, which inevitably moderates expressions of opinion.

I’m not trying to defend the public service – which mostly seems to do a fairly lousy job of (non-detailed) analysis and policy advice. But they are in a different position (with different incentives) to individuals, whether academics or independent commentators like me. Indeed, if I were fishing for consultancy contracts, i probably wouldn’t say many of things I do.

The Productivity Commission should be able to be different – doesn’t depend on a day to day relationship with a specific minister.

LikeLike

And there we go down again – inflation at 1.1%.

Sorry not strictly relevant – but as you have been predicting….

LikeLike

Predicting low inflation is the easy part. Anyone in business or individual trying to borrow from the banks at the moment will tell you how difficult it is to borrow at the moment. A lot of it being directed by the RBNZ. Michael’s solution so far is to drop the OCR would be woefully inadequate as a response if it is countered by the restriction in the lending.

This is similar to 2002 to 2007 but in the reverse when the RBNZ was pushing for the OCR to 9% but did not put the handbrahe on the low documentation loans allowing bankers to lend indiscriminately.

2 key elements are in play, Lending interest rates and the availability of the lending.

LikeLike

Nine to Noon said in the Asia Pacific region an intense period of air traffic growth is forecast with visitor numbers expected to reach 4.5 million by 2022 99% arriving by air.

https://www.radionz.co.nz/national/programmes/ninetonoon/audio/2018641018/what-next-gen-air-traffic-control-means-for-our-skies

Two Christmas holidays back someone said “New Zealanders can’t just expect to go to the beach and find a park (or similar).

LikeLike

4.5 million by 2022 looks rather light given that NZ alone will experience 4 million visitors this year already in 2018. Expect more chefs and cleaners paid $50k a year.

LikeLike

Your post left me wondering what Germany’s immigration rate was when Europe was receiving a massive influx of ‘migrants’ (including refugees) from (mostly) the Middle East fleeing the troubles in Syria and Iraq.

According to Eurostat, Germany received 1.023 million migrants in 2016, including all the refugees – an increase of around 1.2% of its population. Net migration to New Zealand in 2016 was around 71,000 – a population increase of about 1.5%.

That’s right, New Zealand’s normal immigration rate was 25% higher than Germany’s in 2016, and Germany’s massive immigration was largely caused by one of the worst humanitarian disasters of modern times, and a bold and ocntroversial move by Angela Merkel to open Germany’s doors in response to this crisis.

New Zealand? Nothing to see here, according to the champions of high immigration.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And Germany’s influx was basically a one-off. In normal times, German population is now flat or tending to fall slightly.

LikeLike

RNZ is doing it’s bit.

[24:00]

Ali Ikram

At the start of each election you have to start a fire. But it is unsustainable in the New Zealand context because of the contribution migrants make. Economically from everything to ah 50% of the doctors recruited since 2010 all the way to the Cambodian bakers who routinely win the great NZ Pie award. To the Filipinos it seems the country can’t do without to milk the cows. So, yeah, it’s an unsustainable argument and that’s why we stop talking about it suddenly – it unravels .

Paul Spoonley

But in a sense there are economic reasons why immigration is so important to us but also sort of personal and national reasons and I think what has been invoked in parts of this election campaign is sot of angst over you know , what this country is becoming. It’s as though politicians are wanting to stand up and say: “this is not what we thought this country would look like in 2017 “

Ali Ikram

Nothing is less convincing than a New Zealander looking up at a butter chicken pie, made by a Cambodian baker while complaining about immigration

[Raucous laughter -edited out]

https://www.radionz.co.nz/national/programmes/smarttalk/audio/201854410/smart-talk-at-the-auckland-museum-immigration

LikeLike

Interesting concept: chicken pie making is beyond NZ abilities so only consecutive skilled Cambodian bakers can make them whereas Kiwis are sufficiently bright they can learn the skills to be a Journalist or a Professor of Sociology.

LikeLike

The producer of the Nation – doesn’t seem to understand Appeal to Authority fallacy.

And Katharine, I take from your comments you disagreed with the panellists and side more with the blogger. All good. But I can tell you without a doubt that you’d struggle to find an expert with a deeper understanding of immigration than Paul Spoonley. And while I don’t entirely agree with Shamubeel on this, if you know anything about him you’ll know it’s preposterous to suggest he’s not on top of the data and analysis on this. He eats it for breakfast, lunch and dinner. Disagree all you like, but don’t be under any illusion that those men aren’t amongst the best read in the country on this matter (and have given it the most thought).

https://www.pundit.co.nz/content/shamubeel-is-right-get-x-real-about-immigration

LikeLike

quote “it’s preposterous to suggest he’s not on top of the data and analysis”

What data?

How can you analyse an absence of qualitative and meaningful data – you cant

This is the period of big-data. Did you know Google has been marketing to governments the infrastructure – the means – of drawing together and summarising that very thing. Did National go for it. Nope. Didn’t think so

You can pontificate – you can hypothesise – but you cant analyse

I could put forward any number of fallacious views and no-one could refute them – but this vacuum we deal in is a perfect environment for anyone who chooses, particularly what someone yesterday characterised as pop-onomists

LikeLiked by 1 person

Based on comments made by Paul Spoonley he falls into the category of ‘straining every muscle to show that immigration is good for everyone’, while failing to muster much in the way of convincing quantitative analysis. Certainly he seems to be the go to guy for media as he is eager to spruik the benefits of super-charged immigration at every opportunity.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Prof Paul Spoonley: First I met a student of his who said he was a great guy. And to be fair I suspect he is. Then I went to a lecture at Massey Uni a few years ago and he started by deciding the distinction between bi-cultural and multi-cultural should be skipped (admittedly this seemed reasonable with it only a one hour lecture – and it is not a subject I worry about but I am curious as to how a sociologist handles it). Then he said his examples of how immigration is bringing new cultures into NZ and changing NZ would be from sport and food. Well there was little to say about food except why wondered can’t Kiwis learn to cook food from different traditions. Then he spoke about sport and clearly he knows little about sport. His examples were Maori’s don’t play posh sports like golf (ignoring Michael Campbell US Open 2005) and Asians don’t play rugby and especially rugby league (Shaun Johnson half Laotian). I would have preferred meatier analysis of FGM and honour killings and attitudes to homosexuality and religion.

Recently he gave a lecture to U3A in Northcote and he does have a great number of interesting stats but he just assumed Northcote was a home of contented Chinese multi-culturalism. I know the Rose society translates its posters into Korean and Mandarin for the Northcote shops; certainly their are plenty of non-Chinese shops and inhabitants. And maybe Northcote is not so peaceful with nearby Tonar St being the only road in North Shore where my daughters were told not to deliver pizzas.

As you say he is over-straining. With more balance I might support/like him. I do believe him when he said he is ex-directory because of threats to him and his family; there really are some nutters out there and who knows if some are violent. Maybe my problem with him is he lives in a posh suburb and just doesn’t see the kind of issues relating to exploitation that Prof Christina Stringer writes about. You would expect a sociologist to be more sensitive to issues relating to class and immigration; maybe he is but doesn’t want to admit them in public.

LikeLiked by 1 person

From a thesis on Pakeha identity

“In contrast with the literature that positions, and sometimes essentialises Pākehā as acolonising identity (Berg as cited in Spoonley, 1995, p. 105), the political and cultural orientation that Spoonley suggests constitutes self-identified Pākehā identity is a postcolonial identity. While Spoonley argues for a Pākehā identity that is postcolonial, both Yeatman and Spoonley do acknowledge the “impossib[ility] of obtain[ing] an unambiguous closure for the label of Pākehā” (Yeatman as cited in Spoonley, 1995, p.86).

In order to support his picture of Pākehā as postcolonial, Spoonley (1995, p. 94) also points to early writings by Ritchie (1992) and by Scott (1981). Along with these postcolonial Pākehā writers, creative, literary writers (Gadd, 1976; Mitcalfe, 1969) worked from the 1960s onwards to produce literature in contrast to existing, colonial, ‘we are one people’, ‘we are a little England’- type discourses. The sidelining of this early literature which wrote of respectful Pākehā-Māori relations and of a Pākehā identity in respectful connection with Māori (Chan, 1989; Evans, 2007) has limited the discursive resources available about the many meanings of being Pākehā.

Spoonley, while bringing this postcolonial orientation to the forefront, describes it as potentially constituting a Pākehā ethnicity characterised by “the resistance to colonialism and its dominant structures and ideologies [and] driven by the desire to restore the integrity of colonised peoples, and to create space for their institutions, practices and values” (1995, p. 94). Added to this, he describes postcolonial Pākehā as developing a steady commitment to biculturalism. I understand Spoonley’s “space” in the above quote to mean the creation of space through the transformation of current ideological, economic, and institutional structures so that tikanga Māori is acknowledged – presently the granting of such space is mostly token only, and often resisted. To support the postcolonial project of valuing the foregrounding and empowering of Māori ways of being, some Pākehā learn te reo and tikanga Māori (Jellie, 2001). In doing so, consideration of another kind of ‘space’ becomes relevant for postcolonial Pākehā and for Māori: that of Māori space for tikanga and te reo, as autonomous from Pākehā. Research into the ways this space is being negotiated or

would best be negotiated is notable for its absence. While Spoonley has asserted a Pākehā identity wedded to postcolonial politics, and while the social project writing of Project and Network Waitangi have outlined the stages Pākehā go through to become decolonised and postcolonial (Nairn, 2001), nevertheless applied research documenting how that postcolonial orientation can be lived is very limited.”

Click to access 02whole.pdf

“Taleb argues that, because scholarly success is determined by other academics in the realm of abstraction, opportunity exists to create intellectually sequestered spaces in publications and institutions. In these spaces, far-flung notions can circulate by catering to an audience of sympathizers unrestricted by competing theories; a rendition of the “echo chamber” phenomenon, in which only reaffirmations of specific views and attitudes are given oxygen. In contrast to the remote academics under discussion, Taleb provides counter-examples of various tradespeople such as bus-drivers and physicians, whose means of subsistence are subject to regular performance reviews and end-consumer satisfaction. They therefore cannot appeal to cadres of sympathetic colleagues for career sustenance. Taleb makes distinctions between the Arts and STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics); because the latter interfaces with material reality, the echo-chamber effect is largely circumvented. Non-consilient attitudes from academics increasingly break the surface of the mainstream, making prophets out of Dr. Saad and Dr. Taleb. Consider the exchange on TVO’s The Agenda during a panel discussion involving, among others, psychologist Dr. Jordan Peterson and Dr. Nicholas Matte, an interdisciplinary historian. Dr. Peterson supports his professional opinion with reference to data from a panoply of fields, many outside his areas of expertise. Dr. Matte’s position as an interdisciplinary scholar, likewise implies a consilient leaning. However, when they discuss gender identity, Dr. Peterson defers to the scientific consensus that gender has a heavy basis in biology, whereas Dr. Matte blithely declares that, “Basically, it’s not correct that there is such a thing as biological sex.”

http://quillette.com/2018/04/08/academias-consilience-crisis/

LikeLike

Gosh Michael, I read your article and thought David Parker had given an awful speech, one where the Ministry of Environment was ignoring their contribution to the housing crisis and one where hard-line punitive environmental regulations on business were being planned.

So I read David’s speech and it said nothing of the sort.

Housing was an issue that David repeatedly returned to and he had what I think is the best explanation so far of the government’s “Urban Growth Agenda” -with a clear description of its five component parts. David also explained that he was working closely with Phil Twyford, who being responsible for Housing, Transport and Urban Development is the lead Minister on this issue.

Michael there is plenty of academic proof that poorly regulated urbanisation does affect productivity. I probably would have stated my case slightly differently than David Parker but fundamentally he is not wrong that there is a misallocation of resources. You can read about this issue here in an article titled ‘Unravelling the strands of the urbanisation debate: To improve urban performance’ . an article that -Phil Twyford tweeted ‘nicely wraps up the current debate’.

View at Medium.com

David clearly has carved out water as an issue he wants to be the lead person for. This seems to be about a division of labour -it is an issue that someone in government needs to take responsibility for -I have no problem with that being David Parker and the Ministry of Environment.

Your statement that regulations are costs is silly. Michael all your career you were a regulator -do you really believe all that effort only imposed costs on others -were there not benefits too?

If NZ gets a reputation as being poor environment regulators then the damage to our export potential would be significant. That is what I understood from David’s speech.

Finally Michael, I get that you are disappointed that immigration has not been cut more significantly. I know that you have a clear macro-economic explanation for your argument. I have some sympathy for your policy proposals, but just because someone has not fully followed your prescribed policy agenda does not necessarily make them confused. as you accuse David Parker of being wrt productivity.

LikeLike

In essence you are arguing “Regulations have benefits, therefore any arguments attributing costs to regulations are silly. That is a logical fallacy. If the benefits of regulations accrue in the short or medium term to someone other than the regulated party, they are indeed costs, because they are not recovered within, say the period in which the units are produced.

LikeLike

Brendon

You take me somewhat by surprise. I didn’t touch at all on the housing reforms section of the speech, which has some welcome notes (although also some questionable ones – eg “elite soils”) partly because he doesn’t attempt to draw links from housing reform to productivity. I’m not sure why: perhaps it was just a long speech, or perhaps in a NZ context he doesn’t find those arguments particularly persuasive (i’ve laid out various reason previously) or perhaps because even for those gains to be there in principle it would involve house and land prices coming down a long way (and the govt seems averse to ever suggesting that – no doubt in part for understandable political reasons).

But where Parker is confused – or comes across that way – is the same way in which Grant Robertson comes across as confused. there is no trade-off between tradables sector investment and turnover in existing houses (even grossly inflated ones). there is a tradeoff between physical investment in building houses and other physical business investment. Their representation of the story is sadly common – I see it in people like Bernard Hickey – but it is still wrong: it simply never deals with the point that their own policies seek and require (rightly given the popn growth) more of scarce real resources devoted to housing.

On regulation, mostly I was a pretty sceptical regulator (most financial regulation has gone too far, and I was proud to be a very junior part of the liberalisation in the 80s. Fortunately monetary policy isn’ty regulatory. Financial regulation is mostly about limiting crises, but most people would accept that the tradeoff for that is some efficiency cost in normal times. Regulation can serve worthwhile ends – as I noted in the environmental case – but that doesn’t mean there is no economic/GDP cost. Child labour laws probably have such costs – doesn’t make them a bad thing, but if you economy had hitherto been dependent on child labour you might hope that someone who called for abolition while at the same time talking of improving economic performance would lay out the mechanisms whereby those two are supposedly reconciled. Parker hasn’t done that in this speech (and, in fairness, neither did the Nats when they adopted their emissions reduction target).

A reputation as “poor environmental regulator” could cost, in principle. I’d be surprised if domestic water quality had such an effect, but I’ve noted previously that one reason for adopting an emissions reduction target, despite what everyone recognises are high abatement costs, if the threat of retailatory protectionism. But again, either outcome will have costs relative to the status quo, and Parker rightly describing the current situation (economically) as poor and something to be improved on. But how?

On immigration, to be clear Labour has (so far) made no changes, and seems to be backing away from its modest promised changes. When they up the ante on the environment, as with the exploration ban, but still talk about improving our economic performance – as the Nats (to their shame) eventually stopped doing – they should be challenged to explain mechanisms. We can’t just assume a magic productivity tree.

As for Parker, I have quite a bit of respect for him, and so would have hoped for more. Sadly, on the evidence of the text he does seem to be confused about the connection between housing failure and economic performance, and also on the evidence there is no sign that – if he has connections in mind – he has told us how the productivity performance is likely to improve, when the environmental ante is being upped (perhaps rightly) and the population pressures are programmed to go on.

Then again, there was that tantalising line “Where we need immigration, it will be more targeted.”. Time will tell whether it foreshadows anything.

Was it a poor speech in my view? Probably not for its target audience (resource lawyers, and people keen to here the environmental story), but it had quite material weaknesses for anyone with more of an economywide economic lens – and he is after all the Minister for Economic Development, and of Trade and Export Growth.

LikeLike

I am off to work soon Michael, I will try to reply this evening : )

LikeLike

“”If the government were to move to phase in a residence approvals target of 10000 to 15000 per annum (the per capita rate in the US)””. This target has been proposed by you and others (TOP and NZF from memory) and since it is simply a match with the USA it seems on the face of it a reasonable target for those who would prefer to get NZ population’s grow under control. However I suspect it is impossible.

Rather difficult to prove since the INZ R1 Residents database is no longer available. But last year when it was available I tracked the category for ‘Uncapped Family Sponsored’ which is basically NZ citizens getting married (or proven serious relationship) to foreigners and choosing to live in NZ which no fair minded person would dream of stopping. This category increased from 9,606 in 2012 to 12,497 in 2016.

This is understandable if you consider the nature of our immigrants: those arriving from countries with no welfare state will mainly chose to live in NZ (I have family members who prove it – however much they love their country of origin when they have children they see the health and educational benefits of living in NZ rather than PNG.)

A second point made by David Goodhart is the varying willingness form relationships with natives. His figures show Caribbean men happy to marry UK girls whereas Indian women have a strong preference to marry men from their country of origin. UK data is only a rough guide to NZ; much depends on wealth with richer immigrants more likely to integrate and religion is a factor and of course how welcome they feel; if you experience racial prejudice you are less likely to form multi-cultural relationships.

Since citizenship takes at least five years this ‘Uncapped Family Sponsored’ is likely to reflect the increasing numbers of Asian immigrants that we have experienced for the last decade. So my prediction is that for the next five to ten years the married category will bring in at least 13,000 per year. Add that to a minimum of another 1,000 refugees and add the essential immigrants – surgeons with unique skills etc. So a realistic target figure would be 15,000 to 20,000. I would be happy for anyone with access to the INZ statisitics to improve my analysis.

Such a target although higher per capita than UK and USA would instantly solve some of the infrastructure problems. Refugees go where the government sends them (Invercargil at present?) and couples share the same property. It does mean an increased demand for health but usually young people forming relationships are healthy. And a increased demand for education but NZ stats correctly defines children of NZ citizen as Kiwi so that is a cost that needs estimating and I prefer to think of all children born in NZ as a benefit not a cost.

LikeLike

Interesting comment Bob. I see the uncapped family issue as less serious (as a constraint on the ability to reduce overall numbrs) than you do. The partner approvals have been in the 10-11K range for the last five years, and the “dependent child” category has increased to just under 2000 per annum. In both cases, these seem to be to a considerable extent complements to people coming in under other streams, and if we cut back those other streams approvals in these uncapped family categories would fall back too. Thus, the numbers of partners from India, China, and the Philippines (as a share of total partner approvals) far exceeds the size of those groups in the resident population (4000 alone), suggesting that many involve marriages for recent arrivals from those countries (by contrast, the UK number of partner visa approvals has been steady for 20 years (and is actually a bit below average now) – probably mostly the “partner acquired in the course of a stint working abroad”. Cut back residence approvals all round, and the partner approvals will drop away (perhaps with a couple of years lag).

Same goes for the “dependent child” category: I put these in inverted commas, as a disproportionate share (roughly half) is from Samoa. It looks a lot as tho the system is being gamed, with people coming in thru the specific Samoa quota (for residence approvals), and then so-called dependent kids being brought in a bit later thru this uncapped route (as I recall, MBIE treats people up to 24 as able to come under this heading). Since I’d scrap the Samoa quota – or markedly reduce it, if being politically pragmatic, I’d expect the dependent child approvals to drop away as well, and I’d also lower that age limit to (say) 18.

There would be a transition. I’d phase in the reduction in the target over 3-4 years. Do so and I would expect that things would settle down with something like 7-8K partners and dependent kids, say 1500 refugees, and the remainder (1-6 thousand per annum) available for very high quality immigrants. Run that approach for 20 years and I’d expect those partner numbers to drop away further (there were 6000 per annum 20 years ago, when we’d already materially stepped up residence approvals for several years). My pick is that we should be left with an annual average of 5000 such approvals. I’d probably happily respecify that target to leave refugees and uncapped family approvals to one side, and explicitly target 5000 economic migrants per annum (in a range 2500-75000).

LikeLike

I don’t consider the 12,500 uncapped family category a serious issue; it is the other 35,000 new immigrants coming in every year that bother me (and I was one of them in 2003). I concur that given 20 years of a sane immigration policy the numbers are very likely to reduce. I made the point to show how changing immigration numbers is like turning a cruise liner and your target cannot be achieved in the next five years.

In terms of demands on infrastructure the biggest factors besides permanent residency are the massive increase in work visas and in the other direction the large numbers of Kiwis emigrating. Easy to reduce quotas for working holiday visas (for example they stopped my French son on his OE 18 years ago) but there is a moral issue when say a foreign care-giver doing a useful job with a work visa being regularly renewed suddenly discovers they have to return home, especially if there are children involved.

Since our government wants to solve the infrastructure issue but doesn’t appear to want to control immigration then the easiest solution is to encourage low-skilled Kiwis to move away which means Australia. Say $5,000 if you have no education or specific skill and you stay away for five years, paid in installments. A very embarrassing policy but then having Kiwi families living in cars is embarrassing too.

LikeLike

Have to disagree with you that getting to 10000 to 15000 in five years “cannot be achieved”. It could. Achieving it in year 1 would also be possible, but potentially disruptive, and I’ve argued for scheduling the reduction in the target over 3 years. For example, from a current midpoint now of 45000 per annum, go to 35000 in year one, 25000 in year 2, and something centred on 12500 in year 3.

Work visas are, of course, a separate issue, but I’ve laid out my policy proposals there. Again, they could be phased in over 2 or 3 years. As I pointed out the other day, the increase in the stock of short-term people here is material, but still a small part of the total immigration policy increase in population,

You might be unbothered about the uncapped family entrants. If they were partners/children on longstanding NZers, I’d agree. As it is, a fairly large chunk of the numbers involve a dumbing-down of the average quality of those getting residence, since they seem to be people who wouldn’t otherwise qualify for entry on their own skill merits, and thus crowd out better people. But I’m not suggesting capping these numbers, just that the numbers will reduce if we make sensible changes to the underlying capped immigration approvals, and the rules around “dependent children” eligibility.

LikeLike

I may be confused by the statistics database. I certainly agree that ‘secondary applicants’ are tied to the primary. Thinking about it I arrived as ‘skilled’ and my wife and her family arrived months later and we had to prove we were living together so probably she was in the uncapped family category. That fits your analysis.

“” If they were partners/children of longstanding NZers “”. I was assuming the uncapped family category was for partners of NZ citizens and that assumption may well be wrong. Citizenship now takes five years. I think we have to accept five years as ‘longstanding NZ’.

Conclusion: I suspect you are wrong about year 3 but would love to see your ‘go to 35000 in year one, 25000 in year 2’.

LikeLike

The small tweaks so far already demonstrates how disruptive tightening immigration can be. 6 strikes in 6 months is just a prelude of more to come. Labour cost is market driven and when you dry up supply of immigrants you can expect the demand for more pay and the associated disruption that worker strikes bring. I think I will stick to my car than rely on public transport where I am hostage to workers demanding more and more pay.

LikeLike

The hilarious irony is the leaders and initiators of these strikes are now very much migrant workers themselves.

LikeLike

The categories for your article are: ‘Emissions reduction, Emissions targets, Exports, Productivity’ not immigration so my contributions have been off subject. The arguments about our dramatic population increase would apply if NZ had no immigration but had family sizes similar to PNG.

Modest productivity gains are continuous from pre-history to today; for example ever larger wheat harvests and cows giving more milk and chickens more eggs and bakers making more loaves of bread per day. For NZ to achieve productivity greater than other countries we need game-changing innovation or a new resource to exploit. The Victorians had railways, coal mines and massive tracts of un-ploughed land so they had wealth creation and population increase dramatically and simultaneously. Our only significant unique resource is our environment.

When I was a chimney sweep’s assistant I discovered NZ has two types of people: those who love the country and could never live in the city and those who tolerate or even enjoy urban life. We will not find innovators among the latter because the maverick risk taking personalities would move to the handful of really big international cities. So we depend on innovation from rural New Zealand. The people who reacted to being cut out of the UK market by inventing new products for new markets; the kind of people who realised a Chinese gooseberry could be called a Kiwi fruit.

Relevant to potential rural innovation are consistent environmental standards. Stricter controls on pollution and clean water will handicap farmers who want to increase their herd or irrigate a crop but will not stop and might even inspire innovation. The key word is ‘consistent’; we need environmental controls and environmental policies that are not a political football.

LikeLike

The Minister’s statement about *speculative* rental housing investment makes perfect sense to me, Michael. I do not think he is confused at all.

This because I equate “speculative investment” as meaning “investment based on expected capital gains”, and this kind of investment is what generates asset bubbles.

Investment in asset bubbles absolutely means less investment in productive assets. IIRC this is one of the lessons of Tirole’s (1985) paper on rational bubbles.

LikeLike

I guess my response is that this seems to conflate (as the minister did) different meanings of the word “investment”. Bidding up the prices of existing houses might well be undesirable, but of itself it does not involve the diversion of real physical investment (national accounts GFCF) from one sector to another. There are arguable channels by which it might – eg wealth effects from higher house prices – but then our consumption/GDP ratio has been flat for 30 years, with no obvious relationship to trends in house prices. In national accounts terms, Labour argues that it is committed to seeing more real resources (more investment) in building houses. All else equal, that will tend to crowd out other investment (national accounts), in the “productive” sector.

I don’t really buy the line that NZ house prices are a bubble, rational or otherwise. They look to me a lot like a level shift response to the interaction between increasingly binding land use restrictions and periodic surges in population.

LikeLike

That bubbles usually*** crowd-out productive investment is well-established and not that controversial. Jean Tirole won the Nobel (memorial) prize; he is no slouch.

Regarding house prices and bubbles: Scarcity is a necessary condition for a bubble to exist. Restrictive LURs in Auckland, for example, *increase* the likelihood that house prices are well-described by the theoretical concept of a bubble.

*** I say “usually” since a quick lit review shows that bubbles can crowd-in investment in a world with financial frictions, which seems like a reasonable extension of the basic model. This strand of literature sounds very Austrian…

LikeLike

Re scarcity, it can be temporary (eg sluggish supply adjustment, or semi-permanent. In our case, it is more like the latter. In the context, I don’t see much that would lead me to characterise the housing market as bubble.

On the crowding-in vs crowding-out issue, as you say it depends on the specification of your model. But also, I think the financial-side models haven’t yet been particularly well integrated with basic macro models. I’d be interested in a plausible narrative account of how – against specific NZ stylised facts – speculation in existing houses has contributed materially to our decades-long low rates of business investment (GFCF in things other than houses).

LikeLike

Asset bubbles are indeed under-studied. There are a few interesting general equilibrium papers out there.

But we also face a fundamental problem in that the term “bubble” is used in different ways. The definition of a rational bubble is something in the vicinity of “a permanent detachment of an asset price from its income stream that is sustained by expected capital gains”. It has nothing to do with the probability of a crash. It has everything to do with whether we can reasonably expect incomes/rents/dividends to catch up with prices.

The bubble narrative that is consistent with NZ-stylised facts is your own over-population narrative (as I understand it) – but the bubble component puts it on steroids.

LikeLike

Yes, I agree re defn of a bubble. But I also don’t see anything terribly anomalous in (in this case) rental behaviour. With the collapse of long-term interest rates one might otherwise have expected sharp falls in real rents in the last 25 years. Artificial land scarcity (accentuated by population pressures) has prevented that. Across the country – Akld might still be an exception – rental yields don’t look wildly out of line with trends in real long-term interest rates.

LikeLike

IIRC the rental yield in Auckland is on the order of 2.5% (or was when I last computed it – approx early 2016). That is based on simple averages – and thus comes with some caveats – but it puts you in the ball park. Is an investor buying for yield at that point – or betting on further capital gains?

Suppose the decline in long term real interest rates is permanent (I am using post-GFC interest rates – since this the period in which AKL prices grew by double-digits year after year). Such a decline would not be exogenous – it would be caused by something – and that something should also be taken into account when evaluating asset prices. One distinct possibility is that it heralds a slow down in economic growth – which would mean lower income growth going forward than in the past.

LikeLike

I certainly agree we can’t treat the fall in real bond yields as exogenous (one of my repeated themes) but it is also worth remembering that nationwide average real house prices haven’t increased very much since, say, 2007 (Akld is, of course, a significant exception).

Re rental yields, remember that a 10 year real bond rate (indexed bond) is only just over 1.5% at present. I’m not sure what an appropriate risk premium is for a residential property asset but I’d be surprised – but happy to be corrected if wrong – if it has ever been as large as a typical equity risk premium (4-7%).

LikeLike

Yes, I agree that a distinction needs to be made between AKL and the rest of the country.

Re real long term rates: In addition to a reasonable risk premium, we’d also want to allow for expected inflation and depreciation, and, where possible, the tax incentive loophole (that will soon be closed). All things considered, I don’t think the average investor is buying for the current yield. Maybe they expect rents to rise substantially – but those are ultimately capped by incomes. Otherwise it remains a bet on further capital gains.

LikeLike

A bubble is a term coined by economists when they do not understand the variables that lead to price increments. Price increments are the result of a myriad of variables across multidisciplines. Economists that are not trained in finance or accounting principles of which most economists are not, just do not understand some of the fundamental drivers of price. To sound knowledgeable they term it a bubble.

LikeLike