Lots of people, even abroad, look at New Zealand’s economy. For example, there are ratings agencies selling a commercial product to clients, and there are investment funds putting their own and clients’ money at risk. And then there are the government agencies; notably the IMF and the OECD.

Every year or so, a small team of IMF economists come to visit for their Article IV assessment. New Zealand isn’t very important to the Fund: we aren’t systemically important, we don’t borrow money from the Fund, and we aren’t even part of any of the country groupings with traditional clout at the Fund (eg the EU or euro-area). And the New Zealand story is complicated – there aren’t other countries much like New Zealand to compare us against and learn from, and especially not in the Asia-Pacific region (the department of the IMF that covers New Zealand). There isn’t much incentive for the Fund to spend much time on New Zealand, or to devote their best people to New Zealand issues, or to do much other than pay polite deference to the preferences of whoever happens to hold office (bureaucratic and political) at the time, spout some conventional verities favouring smart government intervention, while burying any scepticism in very careful drafting. We might deserve better than we get – after all, we are a member just like all the other countries – but to expect better would be to let wishful thinking triumph over (very) long experience.

But because the IMF’s report on New Zealand is published, and because the mission chief makes themselves available to the local media, the IMF team’s views tends to get some local media coverage. The latest report – in this case the three page concluding remarks from the just-completed mission – came out yesterday.

As has become traditional, they tend to laud New Zealand’s cyclical economic performance

New Zealand has enjoyed a solid economic expansion in recent years. Construction and historically high net migration have been important growth drivers. Accommodative monetary policy, increasing terms of trade, and strong external demand from Asia have supported activity more broadly.

As it happens, on the IMF’s own numbers, growth in real per capita GDP in New Zealand over the last five years has been nothing spectacular – among advanced countries we’ve been the median country and the advanced world hasn’t done that well. And nowhere in the report do they even allude to the fact that almost all that New Zealand growth has resulted from more inputs, and that productivity growth has been near-zero for much of the last five years. From an international organisation that emphasises the importance of open trade etc, there is also no mention at all of the fact that exports and imports have been shrinking as a share of GDP.

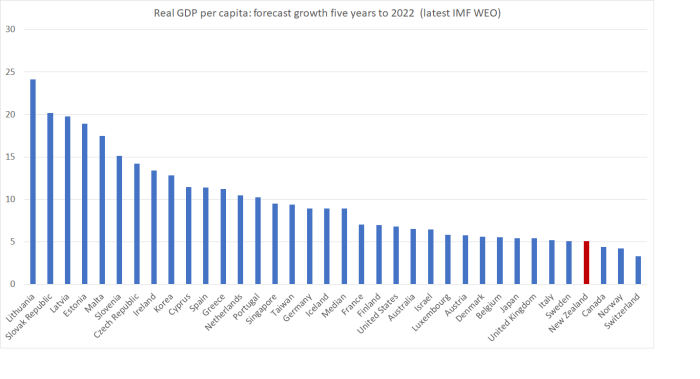

They also tell us that “the baseline economic outlook is favourable”. Perhaps, but their own numbers say something a bit different. Here is a chart of the IMF’s own forecasts for growth in real per capita GDP for the five years from 2017 to 2022.

Not only do they forecast New Zealand’s growth rate to slow (whereas the median country’s growth rate is forecast to accelerate) but on these projections we are expected to have one of the slowest (per capita) growth rates of any advanced country over the next five years. Perhaps there is some productivity miracle embedded in these numbers – the IMF doesn’t produce the breakdown of their growth forecasts – but it looks as though they expect another half decade when we drift a bit further behind. Strangely, none of that showed up in ysterday’s statement.

What of macro policy (monetary and fiscal)?

Here is what they have to say on monetary policy

Current monetary policy is appropriately expansionary. The policy settings are robust to current uncertainties. A precautionary further easing would raise risks of a steeper tightening if inflationary pressures emerged sooner than expected, given that the economy appears to have been operating close to capacity for some time. On the other hand, a premature tightening could prolong price setting below the mid-point of the target range, given persistently low inflation in recent years.

But this is pretty vacuous. Getting policy wrong is, rather obviously, a bad thing. But it is nonsense to suggest that current policy is “robust to current uncertainties”. After all, if inflation ends up staying persistently low, then not to have eased earlier would have risked inflation expectations falling away, and more people being unemployed than necessary. All they are really saying is “we believe – as we have for years, wrongly – that inflation is about to start rising back to the target midpoint, and if so current policy will prove to have been appropriate”. But this was the same organisation that only a few years ago was cheerleading for the ill-fated 2014 Wheeler tightening.

(And one might have hoped that the IMF – in principle able to take a longer-term perspectives – might have been pointing to the risks, of rather limited monetary policy capacity, in the next recession and encouraging the authorities to be taking steps now.)

What of fiscal policy?

The strong fiscal position provides space to accommodate the needs from strong economic and population growth. Compared to the time of the last Article IV Consultation, the updated baseline expenditure path already incorporates higher infrastructure spending and new growth-friendly measures, as discussed below. The continued political commitment to budget discipline and a medium-term debt anchor in New Zealand is welcome. With the country’s strong fiscal position, there is no need for faster debt reduction beyond that outlined in the 2017 Half Year Economic and Fiscal Update. Stronger structural revenues, such as from higher-than-expected population growth, should be used to increase spending on infrastructure and other measures that would strengthen the economy’s growth potential.

This paragraph just exemplifies how the IMF has – at least for tame untroublesome countries – ended up too often as a mouthpiece rehearsing the preferred lines of whoever holds office at the time. Contrast the tone with these lines from last year’s statement.

Current budget plans appropriately imply a counter-cyclical fiscal stance going forward. Stronger-than-expected revenue for cyclical reasons should be used to reduce public debt.

With not a hint that anything fundamental has changed to justify the change in advice, except the government……

The Article IV mission still seems as mixed up as ever on housing and associated risks. They’ve been enthusiastic supporters of LVR controls – never even alluding to the efficiency or distributional costs – as if the basic issue in the housing market had been inappropriate credit availability. Thus they can write

Household debt-related vulnerabilities are expected to decrease following recent stabilization. Macroprudential policy intervention contributed to slowing household debt growth, and momentum in house prices moderated last year. While housing demand fundamentals remain robust under the baseline outlook, the soft landing in the housing market should continue, reflecting increasing supply and, in the medium term, gradually rising domestic interest rates.

But then later in the report they talk at some length about the various measures – some concrete, some (at this stage) still promises – the government is planning to affect the housing market. Perhaps the IMF doesn’t believe those measures will actually do much, in aggregate, but there is no discussion at all about how fixing the housing market would (desirably) actually lower house and urban land prices. Stress tests the Reserve Bank has undertaken suggest banks can cope with big price falls, but the possibility of such an adjustment doesn’t even rate a mention in this statement.

The Fund is clearly not enthusiastic about the government’s foreign house buyer ban (emphasis added)

The proposed ban in the draft amendment to the Overseas Investment Act is a capital flow management measure (CFM) under the IMF’s Institutional View on capital flows. The measure is unlikely to be temporary or targeted, and foreign buyers seem to have played a minor role in New Zealand’s residential real estate markets recently. The broad housing policy agenda above, if fully implemented, would address most of the potential problems associated with foreign buyers on a less discriminatory basis.

But, as I noted, in the unlikely event that a broad housing policy agenda was fully implemented, it would be likely to lower house prices considerably, which surely should rate a mention from the IMF?

The IMF doesn’t know a lot about structural policies – ones that might actually make a difference to productivity (indeed, in New Zealand’s case it is either unaware – or too polite to mention – pressing productivity failures). But that doesn’t stop them devoting a fair chunk of a short report to what they call “Supporting Productivity and Inclusive Growth”. Here, I think it is fair to say, they aren’t entirely convinced.

Thus

The proposed minimum wage increases out to 2020 could help ease income inequality.

But do notice the “could” in that sentence. And the Fund certainly doesn’t seem to buy the story sometimes heard here, suggesting that higher minimum wages will raise productivity (beyond any averaging effect of simply pricing out the lowest skilled people). And

Free tertiary-level education and training for at least one year could boost human capital.

Notice the “could” again. And

Tax reform could play an important role in shifting incentives toward broader business investment.

Again…not a great of confidence that these things “would” make a difference. Then again, there is little sign that the IMF team really understands the issues.

There is also a “should” – highlighting, diplomatically, something that isn’t happening

The new Provincial Growth Fund should ensure project selection that helps regions to benefit from income gains more in line with the major urban centers.

But even that implies that the IMF see the PGF as primarily an income distribution tool, not one – as the government would have us believe – of lifting the underlying economic performance of the regions. But scarily, the IMF seems signed on to the idea of the PGF

It can also be an appropriate tool to relieve pressures on the major urban areas by encouraging movement of population into the regions.

It would be interesting to see the IMF’s analysis justifying government interventions to try to encourage people out of the cities. Ideally, people will flow towards economic opportunities……which either haven’t been there in some of the regions the government worries about, or which the government is in the process of taking away (eg oil and gas exploration).

There is just one element of this structural agenda the IMF is sure of, as both the IMF and OECD have been for years.

The agenda appropriately focuses on lifting R&D spending in New Zealand to 2 percent of GDP. An R&D tax credit, if well designed, would be an efficient instrument to support R&D spending in the business sector.

Note that change of wording: “would”. I guess such a scheme “will” put money in the pockets of some firms. But whether it encourages more worthwhile R&D – and surely the most worthwhile R&D must already be being done – is another matter. And there is no sign that the IMF has ever considered what structural reasons there might be why firms in New Zealand – or considering being in New Zealand – haven’t found it profitable to undertake more R&D spending. Astonishingly, writing about in a country with a real exchange rate persistently out of line with widening productivity differentials, there is no mention of the real exchange rate at all. And if anything is IMF territory, surely it would be exchange rates?

In the end, these days I wouldn’t think better or worse of a policy position because a visiting IMF team favoured it, or opposed it. After all, on macro policy quite possibly the position they hold today will be reversed next year (as we’ve seen happen on fiscal policy). On other things, they show little sign of having thought hard about the New Zealand issues. That’s a shame, but it seems to be a fact of life now.

Sorry about this being a long comment, but seems like April is the season for country/sector reports and there has been a fair bit to read. And the thing that has struck me from reading a few of them is how little we invest in innovation and growth as NZers, while at the same time complaining about how poor our true economic performance (per capita & productivity) is and wringing our hands about why? It’s like we (read: the media, pop-onomists and pop-liticians) see the really stark numbers and evidence and then go off on a tangent based on anecdotes and uninformed assumptions (which is why I like this blog given it’s relentless focus on data and evidence).

Examples:

MBIE just published its report into NZ manufacturing:

Click to access manufacturing-sector-report-2018.pdf

The R&D stats in that aren’t pretty reading (albeit a bit out of date) with overall R&D as a % of GDP at 1.3%, far below the OECD average of 2.4%. They include a ranked list and it’s quite enlightening.

We also had the Startup Genome 2018 global report come out yesterday which has a couple of pages on NZ (picked up in an article in the NBR today): https://startupgenome.com/report2018/

The Genome report highlights that NZ punches above its weight in some areas (global connections, no surprises as we are a small, trading nation that has only relatively recently gone from trading goods and services externally to trading bricks and mortar internally) and referred to recent increases in startup capital availability. They highlight that NZ needs to attract skilled people and produce more large scale winners/exits to accelerate start-up ecosystem growth (which to me flags up the importance of having the capital resources to grow companies bigger and attract said talent and exit $$$…).

That in turn appears to draw on the Angel Association/PwC report of a couple of weeks back highlighting 2017 as a record year for seed/angel investing: https://www.pwc.co.nz/news-releases/2018-news-releases/2018-04-06-nz-startup-investment-reaches-record-level.html

Hooray for 2017, but this is all in a NZ context versus a very low base. If you normalise numbers on a population basis, NZ’s record year in 2017 of $86M invested in seed/Angel investing is about $20/capita. The USA (according to their Angel Capital Association) invested US$24B in same stage companies in 2015, or around NZ$100/capita on today’s FX. My understanding is that the UK is around double our level per capita. So although we are improving, we are way off the pace vs where we should be for our size (i.e. we should be investing $170M+ per annum just to draw level with the UK per capita).

You then look at institutional investment into early stage companies (i.e. “Venture Capital”, which comes in after seed/angel funding) and AVCAL (the Aussie VC Association) highlighted that in 2016 Venture Funds in the USA raised US$128/capita in funding; Australia raised US$18/capita but they then more than doubled their fundraising in 2017 so they are tracking now around US$40/capita (or ~NZ$55).

When was the last year that we saw any NZ Venture Capital funds raised at all, let alone NZ$250M in a single year? And remember that these global markets are raising money for investment EVERY YEAR so each year we miss out, the funding gap for the underlying companies gets bigger and bigger and the harder it is for them to scale and win in a competitive global market.

Also note that this is all Venture Capital that I’m referring to, and not the later stage Private Equity of which there are many NZ funds playing (buying corporate division carve-outs and established businesses off founders).

Which all brings us back to how we can change things and get more investment in innovation so we can change the game in productivity and national income growth. How do we change the incentives and reduce the barriers (both real and perceived) for early stage investments?

NZ is poorly capitalised across the board (last time I looked, the NZX market cap:GDP was around 50% whereas the rest of the developed world is 100%+) but the worst funded segment of the market is the innovative/growth end that the country is reliant on to drive future national performance and prosperity.

The one thing pop-onomists (from Eaqub to Latta to Morgan) seem to agree on is that we aren’t going to get rich as a country selling houses to each other…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting comment/links thanks. My starting proposition is that R&D tends to happen, and capital – whatever stage – tends to flow towards, profit opportunities (actual and expected). As I’ve noted in earlier posts Germany and Switzerland (i think – maybe Denmark) have above average rates of R&D spend, and no tax incentives/credits. My model is one in which remoteness is always going to be a handicap, but a real exchange rate out of line with fundamentals also matters a lot, and something can be done about that. With, say, a 30% lower real exchange rate, many more activities would be prospectively profitable here.

I will be writing about that manufacturing report. I went to an MBIE presentation on it last week, pre-release, which was one of the worst public sector presentations i’ve ever been too (which is saying something after 35 years).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting thing about the MBIE one is their short form overview slide. Key challenges section talks a lot about small local market and geographic isolation behind an impediment to international competitiveness. To be fair they also do mention shallow capital being an issue too. Geographic isolation is an issue (but I’d say far less so these days) but (relatively) small domestic markets didn’t hamper the likes of Norway and Taiwan producing global champions in high value manufacturing…

LikeLike

Yes, that claim about the role of size (and all the head nodding in the audience) was what prompted my series of posts in the last 10 days or so about the relationship (lack of) between country size and economic performance.

Re distance, there are some reasons why it should matter less (the obvious one – Skype, email, internet more generally) but a fair number of economists argue (and I’m persuaded) that in many areas it is mattering more than ever. 120 years ago all it took to export wool was a buyer’s rep in NZ, or a seller’s rep in London (or wherever). Homogenous product, with little product innovation from decade to decade. These days many products have much more complex supply/value chains, frequent innovations and adaptations to market, and dependence on concentrations of specialist skills (whether design, legal, finance) or whatever. It seems at least not inconsistent with our experience – the smart innovative companies that start here, but very rarely stay here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Further – product lifespans are shrinking faster which makes it more difficult to get a new product into the local market, perfect it then attempt the global market. Generally that means if it is a worthwhile concept the bigger fish will buy it out. Or it will languish and die.

LikeLike

Yes, so distance is becoming a bit less of an issue for our (or Australia’s) commodity exports (but it wasn’t a huge issue there even 50 years ago), but becomes more problematic for many of the things firms in other advanced countries, closer to centres of world economic life, are increasingly selling. To the extent we can continue to generate productivity growth in the natural resource based industries we can maintain v high living standards for a small population, but it is very hard to get high living stds for a rapidly increasing population.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Small population

A rapidly increasing population has become self-fulfilling and self-perpetuating. The outcome of uncontrolled mass-immigration has, without requiring them to build a new house, led to an imbalance which has led to unreachable (unaffordable) housing prices in the main job-market, which has in turn led to the postponement of family formation among the domestic young, which in turn has led to them postponing or cancelling their breeding plans, which in turn will lead to the need for the next wave of unplanned, uncontrolled mass migration. Will it ever stop?

LikeLiked by 1 person

a reflection on how distance colours your view

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve been a bit of a sceptic on that Royal Commission, but I guess at least we get to free ride: if it really uncovers severe problems that warrant a policy response then – given that many of the banks are the same – we will be well placed to draw on those findings without the expense of our own RC.

LikeLike

Having lived there for a period including the chase for Skase and becoming sedated by the drip-feed of some of the astonishing antics the banks were performing and the demands for something to be done about it and the protection the banks were given by the Liberal Party, it seems the king-tide has finally boiled over and the intention is now to have all the dirty-washing and rat-baggery paraded in front of the public as a catharsis.

A byplay is the number of NZers involved. AMP is the one currently in the dock, who just last year appointed Jack Regan as CEO (from AMP NZ) and now he is front and centre admitting to AMP intentionally and deliberately breaking the law. Remember Ralph Norris? and his successor.

The top 4 banks are in the top 10 ASX companies. They’re large, and 1% jiggery-pokery is a lot of loot

It’s a public display exercise. However there could possibly be some anti-trust recommendations that they be forced to disgorge their private-wealth divisions and possibly their insurance divisions. That wouldn’t be a bad thing.

IMO the only difference between there and here is the NZ media’s disinterest in following this stuff in preference to following the Kardashians and other mind-numbing stuff that can be cut and paste. The AU media is willing to go after the big-end of town like a rat-up-a-drainpipe whereas the NZ media are captive of the big-end-of-town

LikeLike