There has been plenty of talk in the last few days about the fiscal pressures the government finds itself facing. There are echoes of the great “fiscal hole” controversy from last year’s election campaign. And so it seemed like a good time to revisit a post I did back then on these issues.

In that post I first explained what Labour had done

Labour has laid out their numbers in a series of summary tables. They have explicitly identified numbers for each of their (revenue and expenditure) major policy initiatives, and made explicit summary provision for the cost of a group of less expensive policies. And they identified how much (or little) still unallocated money they would plan to have available. The resulting operating surplus numbers are almost identical to those in PREFU, but where they do take on a bit more debt – to fund NZSF contributions and the Kiwibuild programme – they also allow for additional financing costs.

And then they had BERL go through the numbers. People on the right are inclined to scoff at BERL and note that they are ideologically inclined to the left. No doubt. But all they’ve done on this occasion is a fairly narrow technical exercise. They haven’t taken a view on the merits of any specific policy promises or even (as far I can see) on the line item costings Labour uses. And they haven’t taken a view on the ability of a Labour-led government to control spending more broadly. They’ve taken the Labour numbers, and the PREFU economic assumptions and spending/revenue baselines, and checked that when Labour’s spending and revenue assumptions are added into that mix that the bottom line numbers are

“consistent with their stated Budget Responsibility Rules and, in particular

- The OBEGAL remains in surplus throughout the period to 2022

- Net Core Crown debt is reduced to 20% of GDP by June 2022

- Core Crown expenses remain comfortably under 30% throughout the period to 2022.”

An economics consultancy with a right wing orientation would have happily signed off on the same conclusion.

But, so I argued, that wasn’t the real issue. I won’t blockquote all this, but what follows is just lifted from the earlier post.

But where there is more of an issue is that Labour’s spending plans on the things they are [explicitly] promising mean that to meet these surplus and debt objectives, on these [PREFU] macro numbers, there is very little new money left over in the next few years. That might not sound like a problem – after all, why do they need much “new money” in the next few years when the things they want to do are already specifically identified and included in the allocated money in the Labour fiscal plan? The answer to that reflects the specifics of how the fiscal numbers are laid out, and how fiscal management is done. Government departments do not get routine adjustments to their future spending allowances to cope with, say, the rising demands for a rising population, or the increased costs from ongoing inflation (recall that the target is 2 per cent inflation annually). Rather, they are given a number to manage to, and only when the pips really start squeaking might a discretionary adjustment to the department’s baseline spending be made. Any such discretionary adjustments comes from the “operating allowance” – which thus isn’t just available for new policies.

You can see in the PREFU numbers. Health spending rose around $600 million last year, and is budgeted to rise by around $700 million this year (2017/18). And then….

| $m | |

| 2017/18 | 16432 |

| 2018/19 | 16449 |

| 2019/20 | 16481 |

| 2020/21 | 16396 |

No one expects health spending to remain constant in nominal terms for the next three fiscal years. But there will need to be conscious decisions made in each successive Budget to allocate some of the operating allowance to health – some presumably to cover new policies, and much to cover cost increases (wages, drugs, property etc, and more people), all offset by whatever productivity gains the sector can generate.

And here is why I think there are questions about Labour’s numbers. By 2021, they expect to be spending $2361 million more on health than is reflected in these PREFU numbers. About 10 per cent of that increase is described as “Paying back National’s underfunding” and the rest is labelled as “Delivering a Modern Health System”.

This is how they describe their first term health policies

Reverse National’s health cuts and begin the process of making up for the years of underfunding that have occurred. This extra funding will allow us to invest in mental health services, reduce the cost of going to the doctor, carry out more operations, provide the latest medicines, invest in Māori health initiatives including supporting Whānau Ora, and start the rebuild of Dunedin Hospital.

That sounds like an intention to deliver materially more health outputs/outcomes (ie volume gains, or reduced prices to users).

In response to Steven Joyce’s attack, Grant Robertson is reported as having told several journalists that Labour’s health (and education) numbers include allowances for increased costs (eg rising population and inflation – and inflation in the PREFU is forecast to pick up) as well as the costs of the new initiatives. Perhaps, and if so perhaps a pardonable effort to put a favourable gloss on the proposed health (and education) spends – ie sell as new initiatives what are in significant part really just keeping with cost and population pressures. I say “pardonable” because governments do it all the time.

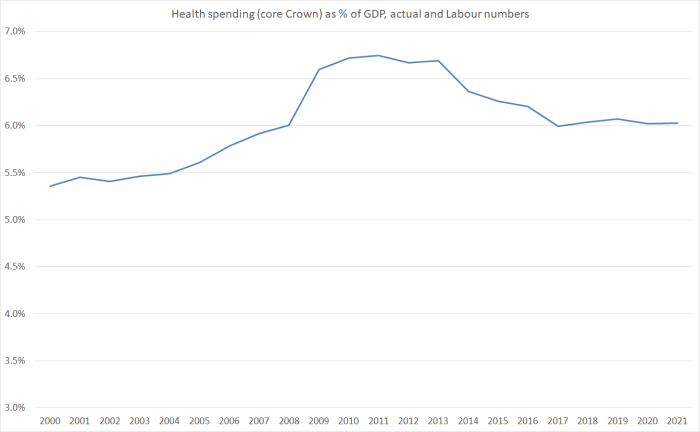

In this chart, I’ve shown core Crown health expenditure as a share of GDP since 2000, and including Labour’s plans for the next three budgets. (Labour show total Crown numbers, but I’ve taken their policy initiative numbers – ie changes from PREFU – and applied them to the core Crown data, which Treasury has a readily accessible time series for. The differences between core and total Crown in this sector are small.)

In other words, on these numbers health as a share of GDP over the next three years would be less than it was for most of the current government’s term, and virtually identical to what it was in Labour’s last full year in government, 2007/08. Some of the peaks a few years ago were understandable – the economy was weak, and recessions don’t reduce health spending demands. But even so, we know that there are strong pressures for the health share of GDP to increase, as a result of improving technology (more options) and an ageing population. Treasury’s “historical spending patterns” analysis in their Long-term Fiscal Statement last year had health spending rising from 6.2 per cent of GDP in 2015 to 6.8 per cent in 2030.

Without seeing more detail than Labour has released there really only seem to be two possible interpretations. Either Labour hasn’t allowed for the ongoing (ie from here) population and cost increases in their health sector spending numbers, or there must be much less in the way of increases in health outputs than the documents seem to want to have us believe (eg “reversing years of underfunding”). One has potential fiscal implications. The other perhaps political ones. Glancing through Labour’s health policy, which seems quite specific, I’m more inclined to the former possibility (ie not allowing for population and cost pressures), but I’d be happy to shown otherwise.

Eyeballing that chart – and as someone with no expertise in health – it would look more reasonable to expect that health spending might be more like 6.5 per cent of GDP by the end of the decade, in a climate where a party is promising more stuff not less, and with no strategy to (say) shift more of the burden back onto upper income citizens.

2018 commentary resumes here: in other words, despite all the talk in their own campaign documents and rhetoric about systematic underfunding of health, Labour’s proposed spending on health – carefully laid out numbers – as a share of GDP just wasn’t consistent with the rhetoric. They – and perhaps even the previous government – may not have been specifically aware of, say, the Middlemore problems, and perhaps more generally things really are worse than they could have realised in Opposition. But it seems implausible to think that a party talking up underfunding – and well aware, for example, of the constant pressure on DHBs to produce surpluses come what may – could have supposed that, on their proposed delivery models and views on entitlements, operating spending on health of only 6 per cent of GDP could have been enough. That was stuff they should have recognised and acknowledged going into the election.

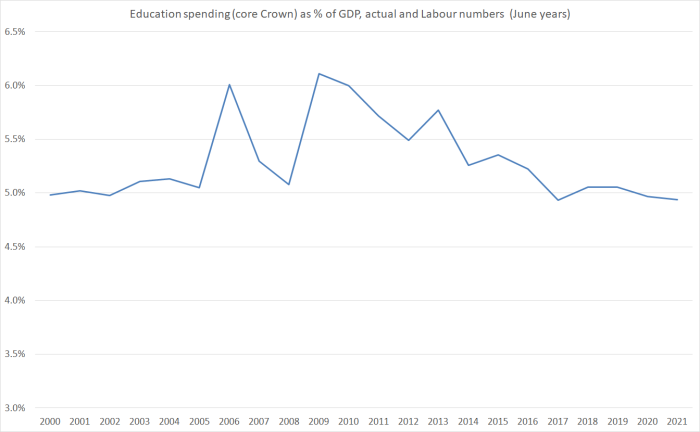

As I noted in last year’s post, one could do the same exercise for education. This is another quote from that post:

One could do much the same exercise for education. Labour has seven line items in its “new investments” table. Most of them are very specific (including increased student allowances and the transitions towards zero-fees tertiary education). There is a general (large) item labelled “Delivering a Modern Education System” but in the manifesto there are a lot of things that look like they are covered by that. There isn’t any suggestion that general inflation and population cost increases are included, but perhaps they are. But again, here is the chart of education spending as a share of GDP, including Labour’s numbers for the next three years.

I’m not altogether sure what some of those earlier spikes were (perhaps something to do with interest-free student loans), but again what is striking is that Labour’s plans appear to involve spending slightly less on education as a share of GDP than when they were last in government. And that more or less flat track from here doesn’t suggest a party responding to this stuff

National has chosen to undermine quality as a cost-saving measure. After nine years of being under resourced and overstretched, our education sector is under immense pressure and the quality of education is suffering. The result is a narrowing of the curriculum, more burnt out teachers, and falling tertiary education participation.

and at the same time committing to flagship policies around things like student allowances and fee-free tertiary study.

Again, it begins to look as though Labour has included in its education numbers the ongoing multi-year costs of its own new policies, but not the ongoing cost increases resulting from wage and price inflation and population increases. Again, I’d happily be shown otherwise.

Of course, there is some unallocated spending in Labour’s numbers, but the amounts are very small for the next few years, and some of these sectors are very large. And although population growth pressures are forecast to ease a little in the next few years, inflation is forecast to pick up and settle around the middle of the target range, so there are likely to be increased general cost pressures (including, for example, wage pressures if as Labour state in the fiscal plan document “by the end of our first term, we expect to see unemployment in New Zealand among the lowest in the OECD, from the current position of 13th”).

How much does it matter? After all, we don’t know many specifics on the policy initiatives National (and/or its support partners) might fund in the next term, and there was the strong suggestion the other night of a new “families package” in 2020 (which would come from any operating allowance). Quite probably the next few years will be tough, in budget terms, for whoever forms the government. After all, the terms of trade isn’t expected to increase further, and inflation is. And there is a sense that in a number of areas of government spending things have been run a bit too tight in recent years. On the other hand, Labour participated in this ritual exercise and it looks as though they may have implied rather more fiscal degrees of freedom than were actually there, if – critical point – they happened to want to produce a surplus track very like National’s.

2018 commentary resumes again. But all that led me to wonder quite why Labour had made the commitments it had. Here is a final, slightly shorter, quote

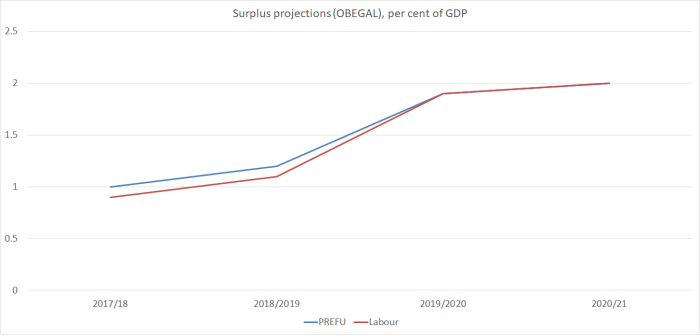

……perhaps the bigger question one might reasonably put to both sides is why the focus on (almost identical) rising surpluses? These are the numbers.

When net core Crown debt is already as low as 9.2 per cent of GDP – not on the measure Treasury, the government and Labour all prefer, but the simple straightforward metric – what is the economic case for material operating surpluses at all? With the output gap around zero and unemployment above the NAIRU, it is not as if the economy is overheating (the other usual case for running surpluses). Even just a balanced budget would slowly further lower the debt to GDP ratios. One could mount quite a reasonable argument for somewhat lower taxes (if you were a party of the right) or somewhat higher targeted spending (if you were a party of the left, campaigning on structural underfunding of various key government spending areas).

When net core Crown debt is already as low as 9.2 per cent of GDP – not on the measure Treasury, the government and Labour all prefer, but the simple straightforward metric – what is the economic case for material operating surpluses at all? With the output gap around zero and unemployment above the NAIRU, it is not as if the economy is overheating (the other usual case for running surpluses). Even just a balanced budget would slowly further lower the debt to GDP ratios. One could mount quite a reasonable argument for somewhat lower taxes (if you were a party of the right) or somewhat higher targeted spending (if you were a party of the left, campaigning on structural underfunding of various key government spending areas).

Labour is promising to spend (and tax – thus the surpluses are the same) more than National. But their commitment (rule 4) was to keep core Crown expenditure “around 30% of GDP”, not “comfortably below 30 per cent”.

28.5 per cent is quite a lot lower than 30 per cent (almost $5 billion in 2020/21 – not cumulatively, as GDP is forecast to to be about $323 billion). And 30 per cent wasn’t described as a ceiling. And in the last two years of the previous Labour government, core Crown spending was 30.6 per cent of GDP (06/07) and 30 per cent of GDP (07/08).

It is a curious spectacle to see a party campaigning on serious structural underfunding of various public services and yet proposing to cut government spending as a share of GDP. It would be difficult to achieve – given the various specific policy promises – but you have to wonder, at least a little, why one would set out to try. We simply aren’t in some highly-indebted extremely vulnerable place.

Here endeth the quotes from last year

I’m not one of those persuaded by the siren calls that the government should be borrowing heavily because interest rates are low. For a start, our interest rates are still among the very highest in the OECD. And interest rate outcomes aren’t the result of some random-number lottery: they are low for a reason (having to do in no small part with future expected rates of growth). I’m also cautious about the lack of “policy space” to cope with the next serious recession. But in the debate around this year’s Budget, or the next couple, most aren’t suggesting the government should rush out and adopt fiscal parameters that might deliver net debt of 50 or 70 per cent of GDP a decade hence. Instead, Labour simply bound itself to the same, arbitrary, net debt target as National had run with, just achieved a couple of years later than National planned to do so.

I don’t agree with everything in this extract from Matthew Hooton’s Herald column the other day, but the gist seems about right.

Robertson has convinced himself that sticking to his commitment is essential to maintain the confidence of the business community and financial markets.

He remembers the Winter of Discontent of 2000 and is determined to avoid at all costs investors and business becoming actively hostile to the new regime.

But this just shows Robertson’s naivety about the business and finance communities and woeful ignorance of what drives confidence in either.

At a net 22 per cent of GDP, New Zealand’s debt is already low compared with the rest of the world. If carefully signalled and communicated by Robertson and his Treasury officials, it is implausible that a further extension of the 20 per cent debt target to, say, 2025, would provoke a materially adverse reaction from the business community or financial markets, especially if emphasis was placed on investments in infrastructure and human capital.

Moreover, the business and financial communities well understand and accept that the fundamental difference between Labour and National governments — at least theoretically — is that the former believes in bigger government than the latter.

And yet – see the graph immediately above- Labour campaigned on continued reductions in government operating expenditure as a share of GDP, all the time claiming that core services were underfunded. And in her press conference yesterday, the Prime Minister indicated that Labour would be sticking to its self-imposed Budget Responsibility Rules. As I illustrated above, under the operating spending limb of those Rules there is plenty of slack, but the binding rule on this occasion is the net debt goal they have committed to. And net debt isn’t just affected by any increase in operating spending, but also in any action the government takes to address claims of (previously unrecognised) backlogs in capital investment.

Labour seem to have first got themselves into this hole from (a) a desperate desire not to leave room to be painted as irresponsible potential economic managers, and (b) an inability to persuasively make an alternative case. And all of this was laid down at a time when, perhaps, it seemed that the chances of having to actually deliver, in government, were slim. But, in the old line, the first rule of holes is “stop digging”. At present, Labour – while claiming things are much worse than even they realised – seem to be setting out to dig themselves even deeper in. In a way, perhaps, it is admirable that they seem to want to follow through on a pre-election commitment. But that narrative about fixing public services, and reversing what they regarded as severe underfunding in many areas (now worse, they claim, than they previously recognised) seemed quite like a pre-election commitment as well, even if it didn’t have precise numbers and dates on it.

(And yes, my natural inclinations are towards smaller government. There are plenty of things I would cut back on, notably addressing NZS issues. This post isn’t an unconditional advocacy for bigger government, or any sort of statement of faith in the likely quality of much government spending, just pointing to the tortured, almost indefensible, logic of the government’s own position. And for those who worry about the interest rate consequences of higher net debt, I tackled that in another post last year.)

The problem with the Labour Government was the desperate lies and promises to get into government. Jacinda Ardern is a queen of lies because she can lie with a poker face. It is incredible how she makes an earnest lying effort to explain away the “No New Taxes” propaganda.

1. Change the Bright Line Tax from 2 years to 5 years is not a new tax.

2. Introduce in March 2019, Ring Fencing of Property Losses is not a new tax

3. Increased Fuel tax is not a new tax

Also the lies on

1. 10,000 Kiwi build houses a year is aspirational and not a promise to deliver

2. 1 billion trees is aspirational and not a promise to deliver

The nurses strike is starting to get ugly. There has been 6 strikes in 6 months so far by Rail workers, port workers and now nurses. This government is losing control over its services due to being seen as soft on wage increments. This is the result of overpromising and under delivering.

LikeLike

Mr Reddell – I know we are on opposite sides of the political divide but I agree with everything you have said. This is an ideologically driven decision on the part of Labour rather than a sound economic one. Their stance is completely illogical. You can’t mend public services by reducing government spending on them.

Is it the legacy of Reinhart and Rogoff? The irrational fear of becoming Greece (even though the two economies are vastly different)? Or just a failure to grasp that a government is not a household? Or total rejection of Keynes despite the natural experiment in fiscal consolidation provided by Eurozone and UK austerity this decade. It is nuts. I’m no National lover but they absolutely did the right thing to expand deficits in the GFC.

Please, if respected economists such as yourself speak up a bit more it will open up political space for the government. Even in the spirit of – “come the next recession and things will turn ugly, do you really want the non-National voting public to go rogue and vote for a NZ version of Cinque-Stelle and Lega Nord?”

LikeLike

I think they just got trapped by a desperate desire to appear responsible (laudable in its way) and none of the political/communications skills to articulate a different vision effectively (and in a way which would have meant they could have handled attacks from the likes of Steven Joyce). if you don’t have that skill set, you fall back on attempting to minimise the (fiscal) difference between you and the Nats, while keeping up the rhetoric in other areas (thus creating the gap between what appeared to be promised, and those fiscal commitments, whereby they nailed themselves to the cross).

I don’t know any economists who are particular wedded to the current fiscal (debt/spending) tracks – as Hooton says, people recognise that left wing govt tends to be a bit more “big government” than notionally right wing ones. Seems to me the real challenge now is a political one: are they willing to say, “we made a mistake last year, and we really regret that. Now we are going to put it right. That does’t throwing out fiscal discipline, or losing sight of limits of debt, but it does mean accepting that huge population growth and surpluses achieved heavily by cutting baselines rather than making clear changes in promised expectations about services, has created pressures that simply have to be resolved.” Of course, even if they did that – and I think it would be sensible – there would still be the subsequent challenge of executing well and communicating well. On neither score does the govt yet seem to be on top of things, and if they don’t fix that then simply easing up on fiscal policy can feed a narrative of being all over the place, rather than the new one they’d be hoping for.

LikeLike

Oh how I wish “narratives” were not so important and sounder economic judgement won the day. This whole ever decreasing public debt thing is all about “optics” – that hideous word my journalist friends always pull on me when I try to forward an argument based on principles or empirical reality – “You’ve gotta understand the optics on this…..”

New boss. Same as old boss.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on The Inquiring Mind and commented:

Michael Reddell gives a clear analysis of why we should cast a sceptical eye over the Ardern regimes current misinformation campaign.

LikeLike

Last thing to vent – there are plenty of people out there with the communication skills to articulate a different strategy – just Labour chooses to ignore them and disassociate from them because they hate appearing left-wing.

They could have organised an economic talk-fest in their many years in opposition with Varoufakis, Krugman, Turner, – a variety of left-wing and heterodox economists, local and overseas. They could have built a counter-narrative around some of the current mainstream economists calls for greater use of fiscal policy. As Slavoj Zizek asserts- even a small struggle on a key issue can be very important politically – like gaining consent for a modest fiscal expansion in these deflationary, stagnant times – that could have been that small, crucial step.

But they didn’t. The risk-averse political optics gang have got control of fiscal policy.

They have no political imagination and their fate might well be that of socialist parties the world over given a downturn. And they can’t say they weren’t warned.

LikeLike

I guess my only caveat to that is that each of those overseas people you cite are coming from places where monetary policy had reached its limits (interest rates zero or below), and the case was partly about stimulation to overall economic activity. Here Labour went into the election conceding National’s claim that the economy is in good shape – a nonsense argument, but accepted. So the arguments around fiscal policy have to be framed differently here.

LikeLike

[…] an economist I don’t have a strong view on what the number should be, although as I’ve noted previously it is curious that the current left-wing government, arguing all sorts of past underspends, was […]

LikeLike